Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Keres Article

Uploaded by

Brianne PattersonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Keres Article

Uploaded by

Brianne PattersonCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine

Volume 6, Issue 1 2009 Article 15

Using the Biopsychosocial Model to Understand the Health Benets of Yoga

Subhadra Evans Beth Sternlieb Jennie CI Tsao Lonnie K. Zeltzer

University of California, Los Angeles, suevans@mednet.ucla.edu University of California, Los Angeles, jtsao@mednet.ucla.edu University of California, Los Angeles, yogahouse@aol.com University of California, Los Angeles, lzeltzer@mednet.ucla.edu

Copyright c 2009 The Berkeley Electronic Press. All rights reserved.

Using the Biopsychosocial Model to Understand the Health Benets of Yoga

Subhadra Evans, Jennie CI Tsao, Beth Sternlieb, and Lonnie K. Zeltzer

Abstract

Yoga is widely practiced as a means to promote physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing. While a number of studies have documented the efcacy of yoga for functioning in healthy individuals and those experiencing illness or pain, biopsychosocial effects have not been detailed. We propose an analogue between the physical, psychological and spiritual effects of practice as espoused in yoga traditions, and the biopsychosocial model of health. To this end, we present a review and conceptual model of the potential biopsychosocial benets of yoga, which may provide clues regarding the possible mechanisms of action of yoga upon well-being. Physical systems activated through yoga practice include musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, autonomic nervous system and endocrine functioning. Psychological benets include enhanced coping, self-efcacy and positive mood. Spiritual mechanisms that can be understood within a Western medical model include acceptance and mindful awareness. We present empirical evidence that supports the involvement of these domains. However, additional well-conducted research is required to further establish the efcacy of yoga for health states, and to understand how posture, breath and meditative activity affect the body, mind and spirit. KEYWORDS: yoga, health, biopsychosocial

This report was supported in part by The Sue Stiles Foundation for Integrative Oncology (PI: Lonnie K. Zeltzer).

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

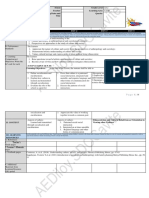

Introduction Yoga is an ancient tradition practiced to promote the well-being of body, mind and spirit. The beneficial effects of yoga are believed to occur through asana (poses), pranayama (breath) and dhyana (meditation) and traditionally, yama (ethical behavior), niyama (self discipline), pratyahara (sense withdrawal), dharana (concentration) and samadhi (deep meditative awareness). Today, yoga is widely used as a means of exercise and relaxation. Despite the ancient origins of yoga as a spiritual and metaphysical practice, the medical use of yoga to promote physical fitness and ameliorate physical complaints may only have gained prominence in the last century, both in India and abroad (Alter, 2004). It is therefore important to understand the contemporary use of yoga for medical purposes, including the development of a model that incorporates a broad range of effects upon health. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the biopsychosocial benefits of yoga, including directions for future research in which mechanisms of action can be further explored. Recent surveys point to the ever-increasing popularity of yoga in alleviating pain, stress and illness. Estimates suggest that approximately 5% of adults in the US practice yoga (Barnes, 2004). A recent study of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) preferences among children at a tertiary pain clinic found yoga to be amongst the three most popular treatments (Tsao, 2007). Despite its popularity, limited research has explored the empirical efficacy of yoga. Even in studies that have addressed yogas effectiveness, the larger question of how yoga works remains outstanding. To date, mechanisms behind the therapeutic effects of yoga remain unclear and a systematic model for understanding levels of action on the entire person has not been offered in the medical community. The intention of this paper is to understand the relationship between yoga used for healthful purposes and the biopsychosocial model of healthcare which explains mind/body relationships in pain, stress and illness. Rather than providing a systematic review of the efficacy of yoga for a single aspect of health, a number of which already exist for cancer, pain and psychological functioning (Bower et al., 2005; Evans, 2008; Kirkwood et al., 2005; Monro, 1995; Pilkington et al., 2005), we offer a model conceptualizing a range of biopsychosocial benefits, which may together impact well-being. We believe the use of such a model is integral in establishing the direction of future yoga research. In order to promote the understanding and ultimate use of CAM therapies within conventional healthcare settings, mechanisms of action should be charted by considering benefits across functioning, including biological, psychosocial and spiritual aspects of well-being. To this end, we present such a conceptual model of yoga on health outcomes (see Figure 1) that can be integrated into current medical science.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Databases that were searched included PubMed, PsycINFO and CINAHL; yoga studies referenced in published papers were cross-referenced, and any studies not in databases, but mentioned in papers were included where possible. Pilot studies, randomized controlled trails (RCTs), controlled trials and single-arm repeated-measure designs which examined the biopsychosocial impact of yoga on health, illness or pain were reviewed. Keywords used in the literature search included yoga, mindful, health, pain, illness, disease, psychology, spiritual, quality of life, mechanisms, and biopsychosocial. Applying the Biopsychosocial Model to Yoga Yoga currently consists of numerous traditions, and while most incorporate posture, breath and meditation, they can vary greatly in execution and focus. We briefly consider two popular styles practiced within the US to illustrate such differences. Iyengar yoga is frequently used in studies of yoga for chronic pain and emphasizes alignment, holding postures for periods of time, and sequencing of postures. The practice is typically individualized to a students ability, motility, and health needs through the use of props and uses specific therapeutic sequences for students with health problems. An extensive teacher training program ensures replication of poses and sequences (Mehta, 2006). Ashtanga Yoga involves synchronizing the breath with a progressive series of postures and the emphasis is on an energetic flow of postures, which are often executed and repeated in quick succession. The use of breath and quick progression of poses is designed to produce internal heat and improved circulation and strength (Haaz, 2007). The ultimate goal of these traditions is to achieve mental, spiritual and physical well-being by establishing balance within the internal and external environment (Taimni, 1961). This goal, when applied to the promotion of health, is compatible with the goal of Western medicine: to establish homeostasis in the body. Current conceptions of health use the biopsychosocial model, which addresses a persons physiology, psychology, environment and behavior to understand how social and psychological factors interact with biology to influence pain, illness and health (Gatchel et al., 2007). The purported action of yoga on well-being is possible when considered from a biopsychosocial model, whereby an individuals mind, body and wider social environment all impact health states. In some diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psychosocial factors including stress and lifestyle choices may explain as much as 20% of a patients disability (Drossaers-Bakker et al., 1999; Escalante & del Rincon, 1999). The combination of body, mind and breath awareness used in yoga is likely to have a corresponding impact on psychophysiological functioning. Indeed, as explored below, yoga appears to produce homeostasis across multiple aspects of an individuals functioning and physiology.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Yoga

Structural/Physiological

Musculoskeletal functioning Cardiopulmonary status ANS response Endocrine control system

Psychosocial

Spiritual

Compassionate understanding Mindfulness

Self-efficacy Coping Social support Positive Mood

Enhanced Functioning

Energy & sleep Quality of Life Strength & fitness Reduced pain, stress & disability

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of the Biopsychosocial Benefits of Yoga

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Biopsychosocial Benefits of Yoga Scientists have long recognized the healthful benefits of exercise, especially for disease, illness and pain states. Exercise, fitness, and musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary functioning are intimately connected. Physical activity has also increasingly been linked to improved mood (Greenwood & Fleshner, 2008). In addition to positive effects on structural and psychophysical outcomes, exercise likely impacts brain chemistry to regulate somatomotor-sympathetic circuits (Kerman, 2008). We propose that yoga shares many of the physical and psychological benefits of exercise, in addition to specific effects not shared by regular exercise. In yoga, the practice of not seeking the fruit of actions, but to practice for its own sake (Mehta, 2006) is in contrast to many forms of physical activity, which often rely upon a comparison to others or pushing oneself beyond limits to define progress. The non-competitive focus on personal development cultivated by yoga is believed to pave the way for psycho-spiritual achievements such as compassionate understanding, or acceptance, and mindful awareness. Other achievements that have been suggested to follow yoga, but not other forms of physical activity, pertain to physiological functioning - including control over bodily systems. Maintaining postures is thought to lead to strengthening and relaxation of voluntary muscles and eventually to control over the autonomic nervous system (ANS) (Vahia et al., 1966). Preliminary support for this notion exists in research demonstrating voluntary control over heart rate after a 30 day yoga intervention (Telles et al., 2004). Empirical evidence for the biological and psycho-spiritual benefits of yoga is further discussed below, and while some findings are similar to those seen for regular exercise, other benefits such as ANS control and increased mindfulness appear to be specific to yoga. Structural/physiological benefits: It is thought that yoga quiets the body as well as the mind through vascular and muscular relaxation (Monro, 1995). Empirical research demonstrates support for this view, as yoga has been associated with benefits across a number of physiological systems. From a basic physical activity perspective, yoga may be particularly suited to people with chronic health conditions. When practiced correctly, yoga is unlikely to irritate inflammation, and yet involves movement to improve strength (Greendale et al., 2002; Haslock et al., 1994), flexibility (Greendale et al., 2002) and range of motion, along with attention to alignment (DiBenedetto et al., 2005; Garfinkel et al., 1994). While more static yoga poses may only possess the metabolic cost of light intensity exercise (Clay et al., 2005), other findings have indicated that intensive poses or sequences, such as surya namaskar (performed for longer than 10 minutes), are in fact associated with sufficiently elevated metabolic and heart rate

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

responses to improve cardio-respiratory fitness (Hagins et al., 2007). In a RCT of 40 healthy 12-15 year-old boys randomly assigned to a yoga intervention for one year, significant improvements were found in body weight, cardiovascular endurance and anaerobic power compared to usual activity controls (Bera & Rajapurkar, 1993). A recent repeated-measures study suggested that practice of surya namaskar represents a promising form of aerobic exercise as it involves static stretching as well as a slow, dynamic component of exercise with optimal stress on the cardiorespiratory system (Sinha et al., 2004). Another study examining a 6-week yoga practice for 20 adolescents found that yoga had an effect on the bodys glycolytic enzymes similar to endurance training (Pansare, et al., 1989). Others have reported the positive impact of yoga on metabolic outcomes, including cholesterol and fasting plasma glucose (Bijlani et al., 2005), as well as a significant reduction in girth circumference (Khatri et al., 2007). However, a number of studies did not include control groups (Bijlani et al., 2005; Pansare et al., 1989; Sinha et al., 2004) and further research is required to establish the metabolic cost of energetic versus less energetic forms of yoga. A number of findings point to the musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary benefits of yoga. It has been argued that the extension and flexion of muscles during yoga poses is associated with activation of antagonistic neuromuscular systems as well as tendon-organ feedback resulting in increased range of motion and relaxation (Riley, 2004). Yoga interventions for individuals with arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions have found improvement in a range of physical outcomes, including pain, strength, joint tenderness, range of motion and disability (Evans, 2008). The cardiopulmonary effects of yoga have also been studied. Consistent with yoga theory that the cells of the body represent pearls of life and that yoga practice supplies ample fresh blood and energy to each cell (Mehta, 2006), a study focusing on mechanisms of action found that slow breathing techniques used during yoga were associated with increased oxygen delivery to tissues in 10 yogis compared to 12 controls with no yoga experience (Spicuzza et al., 2000). A study comparing the pulmonary functioning of 60 athletes, yogis and sedentary controls found similar lung functions for the yogis and athletes, which were significantly enhanced compared to the controls (Prakash et al., 2007). As discussed below, yoga practice has also been associated with improved respiration and heart rate variability measures. A recent review concluded that yoga has cardiopulmonary benefits for healthy individuals and possibly those with musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary conditions (Raub, 2002). In this review, likely physiological mechanisms were identified, including increased skeletal muscle oxidative capacity, decreased use of glycogen and slow increase in lung capacity. Empirical research is required to further test these mechanisms.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Studies linking yoga with autonomic nervous system (ANS) functioning have found reduced stress responses, including blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration (Bharshankar et al., 2003; Granath et al., 2006; McCaffrey et al., 2005; Sarang, 2006), especially for illness states such as coronary artery disease (Sivasankaran et al., 2006) and hypertension (McCaffrey et al., 2005). In addition, a 10-week course of yoga for patients with refractory epilepsy found enhanced parasympathetic activity and a decrease in seizure frequency following yoga in a group of 18 patients compared to 16 exercise control patients (Sathyaprabha et al., 2008). A recent study reported that heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of cardiac autonomic activity, increased in a group of 11 yogis following a class of Iyengar yoga compared to a placebo session and a group of regular activity controls (Khattab et al., 2007). An increase in HRV parameters is consistent with healthy functioning and a reduced risk of heart disease. Monitoring breath during yoga may be especially relevant for ANS functioning. Voluntary control of breath has been associated with increased HRV (Lehrer et al., 1999), and it is possible that breath awareness during yoga may produce autonomic control similar to that seen during biofeedback. This research provides preliminary support for the positive effects of yoga on regulation of arousal systems. Yoga may have differential short-term versus long-term effects on the ANS. During active poses, heart rate and respiration may increase consistent with physical activity (Sinha et al., 2004). However, during and following savasana, the restful meditative pose that concludes most yoga classes, parasympathetic activity consistent with relaxation and a reduction in physiological arousal is apparent (Sarang, 2006). Yoga practice also appears to result in increased control over ANS responses such as heart rate. For example, after a month of yoga practice, a group of 12 healthy participants had a lower resting heart rate after the intervention compared to a matched group of 12 regular activity controls; the yoga group was also able to significantly lower their heart rates when given instruction to do so (Telles et al., 2004). Although larger RCTs are required to replicate these findings, the study suggests physiological benefits of yoga consistent with regular exercise in the form of lower resting heart rate, in addition to yoga-specific psychophysiological control. It is also possible that different systems of yoga produce differential effects on the ANS. Fast moving yoga poses as seen in Ashtanga yoga may lead to short-term physiological arousal, whereas restorative practices commonly cultivated in Iyengar yoga may be associated with short- and long-term parasympathetic nervous system dominance. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific and differential activity of the ANS during and following various traditions of yoga. Yoga also appears to impact the endocrine system. It is hypothesized that asana practice massages the internal organs, resulting in enhanced blood circulation, glandular functioning and ultimately the balance of hormone

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

production (Monro, 1995). Specific poses, such as savasana, may modulate brain chemistry, particularly the hypothalamus (Bose et al., 1987), which links the nervous and endocrine systems and is involved in the action of stress hormones. Empirical studies examining neuroendocrine changes following yoga have generally focused on cortisol, a measure of stress response system activation. Most studies have reported a reduction in cortisol with yoga practice (Kamei et al., 2000; Vedamurthachar et al., 2006; West et al., 2004). Although these results are compelling and suggest a lowered stress response following yoga, only one study used a randomized controlled design (Vedamurthachar et al., 2006). This studys exclusive use of participants with alcohol dependence and Sudarshan Kriya Yoga, a practice of yoga focusing on breath rather than posture, also limits generalizability. Increase in nighttime plasma melatonin, a hormone associated with sleep quality, has been reported following yoga in a small group of experienced meditators (Tooley et al., 2000) as well as in 30 healthy men aged 25-35 years randomized to a 3 month exercise control group or a yoga intervention (Harinath et al., 2004). These findings provide support for a possible mechanism linking sleep quality and yoga (Khalsa, 2004) and lend preliminary credence to yoga theory maintaining that yoga practice enhances and normalizes endocrine function. Further scientific studies are required to understand the full range of endocrine functions that may be impacted by yoga. Psychological benefits: Yoga has a number of positive effects on psychosocial functioning which have been reported in healthy, pain and stressed individuals spanning a wide age-range. Psychological effects include increased self-efficacy, coping, social support and positive mood. In a healthy group of 194 participants enrolled in a 3 month community-based yoga program, significant pre-post improvements on depression, anxiety and self-efficacy scales were reported (Lee et al., 2004). In a group of 12 caregivers to older dementia patients, a six-week practice of yoga and meditation revealed significant pre-post improvements in depression, anxiety and self-efficacy (Waelde et al., 2004). An RCT of adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome was found to reduce anxiety and adaptive coping following four weeks of yoga home-practice compared to waitlist controls (Kuttner et al., 2006). An RCT examining yoga (unspecified tradition) for headache also reported improved coping and headache symptoms after a 4-month treatment of yoga compared to standard treatment controls (Kaliappan, 1992). In another RCT, Woolery et al, (2004) reported reduced depression and anxiety after a 5-week Iyengar yoga practice in mildly depressed young adults compared to waitlist controls. A recent single-group outcome study found reduced depression, anger, anxiety, and neurotic symptoms in 17 patients with unipolar major depression in partial remission who completed an Iyengar Yoga intervention (Shapiro, 2007). Reductions in low frequency heart rate

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

variability were also evident post intervention, indicating a biological reduction in stress responsivity. Yoga has also been linked to social benefits, consistent with the notion that exercise performed in a group can promote social well-being, which in turn is important for functional status in chronic disease (Weinberger et al., 1990). Yoga classes have been associated with social benefits in a range of populations, including a RCT of yoga for a multiethnic group of breast cancer survivors (Moadel et al., 2007), general cancer patients (DiStasio, 2008), and a pilot study treating osteoarthritis of the knees (Kolasinski et al., 2005). Two reviews examining yoga for depression and anxiety have underscored the promise of yoga for improving mood. Out of five RCTs of yoga for depression, beneficial effects were reported in four (Kirkwood et al., 2005). All eight randomized studies of yoga for clinical anxiety disorders reported a reduction in symptoms following yoga (Pilkington et al., 2005). Findings did not appear to vary as a function of symptom severity, suggesting that benefits may be available to individuals with mild depressive symptoms and anxiety through to clinical level symptomology. It has been argued that increased mastery of poses, emotional release, tolerance of vulnerability related to opening of the body posture, and a sense of relaxation in restorative poses all contribute to the positive effects of yoga on mood (Woolery et al., 2004). The mood enhancing effects of yoga could arise from a number of sources. Similar to exercise, yoga may have biochemical benefits that are related to psychological functioning, as well as provide resources for coping and selfesteem which impact psychological well-being. A recent study found a 27% increase in the neurotransmitter GABA, low levels of which have been linked to mood disorders, in a group of 8 yoga practitioners compared to 11 controls who spent time reading (Streeter et al., 2007). These findings point to possible biochemical mediators in the effect of yoga on functioning. Consistent with the biopsychosocial model, positive psychological functioning is likely to lead to improved physical functioning, especially in patients experiencing chronic pain and illness. For example, positive coping, including higher pain control and rational thinking, have been linked to improved pain scores in young rheumatoid arthritis patients (Schanberg et al., 1997). Health-related self-efficacy, or the tendency to persist in health behaviors despite obstacles, has also been related to decreased pain behavior (Buckelew et al., 1994) and fewer somatic symptoms in chronic pain patients (Bursch et al., 2006). The observed improvements in mood, adaptive coping, social support and selfefficacy following yoga suggest that the healthful effects of yoga may at least partially be mediated by enhanced psychological functioning.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Spiritual benefits: Related to the psychological benefits of yoga are the spiritual underpinnings of yoga. Spirituality has emerged as a core domain in quality of life assessments in patient populations, including oncology patients (Whitford et al., 2008), and is increasingly considered an integral part of health (McBrien, 2006). Working definitions of spirituality include a system of beliefs or values (which can be religious or not), life meaning, purpose and connection with others or a transcendental phenomena (Sessanna et al., 2007). Yoga practice involves a system of beliefs, values, life meaning and a connection with others that can be practiced either as a religious path or secularly. We explore two such spiritual contributions of yoga: compassionate understanding, or acceptance, and mindful awareness. It is worth noting that in Western science, concepts such as acceptance and mindfulness may overlap with psychological functioning and are often accepted within mainstream psychology, such as in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Fletcher & Hayes, 2005). A guiding principle of yoga is to foster the resilience to work with, or accept, negative forces in life (Raub, 2002). An individual with debilitated health would be encouraged to accept his or her limitations, yet continue to pursue a full practice of yoga, using props to support poses and ultimately to complete life tasks despite physical challenges. Yoga can therefore be associated with the development of skills in mastering difficulties in life, which may extend to dealing with suffering and pain (Raub, 2002). Regular practice of yoga may act to redefine an individuals experience of pain or difficulty, encouraging acceptance of pain, and the continuation of functioning despite pain (Iyengar, 2005). This notion is compatible with Western medicine, where acceptance of pain is viewed as important for those with chronic conditions to persist in regular activity (Mason et al., 2008). In a study examining the effects of yoga on healthy women, measures of life satisfaction increased while other personality variables including excitability, aggressiveness and somatization decreased in a group of 25 women practicing yoga compared to a control group of 13 women who read in a relaxed position for the same duration (Schell et al., 1994). These findings point to a possible reorientation in understanding or acceptance of oneself through yoga. Further research is required to elucidate whether yoga allows individuals with medical conditions to reach a level of acceptance or peace regarding their health status, abilities and limitations. Although untested, a possible derivative of acceptance through yoga is a corresponding ability to see benefit within hardship. Benefit finding, or the tendency to look on the bright side in the face of hardship is being studied in patient populations within health psychology. Women with breast cancer often report personal or social development resulting from the experience (Sears et al., 2003), which when used in expressive writing, is associated with reduced physical symptom reports and fewer medical appointments compared to writing about facts

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

(Low et al., 2006). It is possible that compassionate understanding towards oneself and others fostered through yoga would facilitate an increase in such benefit finding. Future research examining yoga for medical conditions should include measures of acceptance and benefit finding. Yoga is also associated with mindful awareness, a concept that has been integrated in empirically validated approaches including cognitive-behavioral therapy (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Mindfulness is an openness or receptive awareness to what is occurring in the present. Meditation and yoga are thought to modify the influence of stress on the mind by strengthening attention or mindfulness (Monro, 1995). Mindful activity through yoga has been found to improve mood and stress (Netz & Lidor, 2003). In this study, 147 female teachers enrolled in yoga, Feldenkrais (awareness through movement), dance or swimming class, and a computer class served as the control group. Mood improvement was evident only in the yoga, Feldenkrais and swimming groups, leading the authors to suggest that mindfulness in activity plays a role in benefit. Yoga generally involves mindful techniques, particularly in relation to ones breath and the physical body, including posture, balance and symmetry. This focus on body, mind and breath in the present moment can then free attention to explore ways of minimizing stress, disability and pain. Understanding of the body is thought to lead to healthy lifestyle choices and control over physiological systems (Khalsa, 2003). Empirical evidence for this notion exists. Heightened attention to alignment has been reported following yoga in a single arm study of 21 patients with hyperkyphosis (Greendale et al., 2002). Mindful awareness has further been associated with a range of positive health outcomes, including improvements in stress, reductions in cortisol levels, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines consistent with immune enhancement as well as lowering of blood pressure/heart rate in cancer patients (Carlson et al., 2007). Enhanced Health Outcomes Following Yoga Multiple research studies have documented the health benefits of yoga, with improvements found across varied aspects of functioning. Recovery of energy levels and sleep are apparent in individuals with chronic illness and stress (Bower, unpublished manuscript; Oken et al., 2004; Telles et al., 2007; Yurtkuran et al., 2007), those with insomnia (Khalsa, 2004) as well as healthy individuals (BoothLaForce et al., 2007; Manjunath & Telles, 2005). Increased strength and fitness have been reported for healthy individuals and those with chronic conditions (Dash & Telles, 2001; DiBenedetto et al., 2005; Garfinkel et al., 1998; Greendale et al., 2002; Haslock et al., 1994). Reduced pain and disability and increased quality of life have also been reported in RCTs for various conditions, including migraine and headaches (John et al., 2007; Kaliappan, 1992), rheumatoid arthritis

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

10

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

(Garfinkel et al., 1998), osteoarthritis (Garfinkel et al., 1994) and chronic low back pain (Williams et al., 2005). Reviews of RCTs of yoga for health conditions, including cancer (Bower et al., 2005), chronic pain (Evans, 2008), anxiety (Kirkwood et al., 2005) and depression (Pilkington et al., 2005) have concluded that yoga is a promising intervention. As also identified in these reviews, research remains limited by a range of methodological issues, including small sample sizes, lack of randomization and control groups, blinding of assessors and use of unvalidated tools. An additional problem limiting much of the literature is a lack of clear description regarding yoga asanas, teacher training and yoga tradition utilized. Despite these issues, the balance of evidence indicates that yoga promotes health-related functioning in healthy individuals and those experiencing illness or pain. Conclusions The bulk of evidence indicates that yoga holds promise in acting favorably upon multiple and widespread aspects of an individuals health. It seems scientifically possible that through yoga, individuals can regulate their body, mind and spirit in such a manner as to produce benefits in biological, psychosocial and spiritual domains. Although we discussed separate effects on physiological, psychosocial and spiritual systems, in reality, yoga is likely to affect multiple systems simultaneously. For example, changes in brain chemistry such as GABA levels and stress hormones such as cortisol may be associated with reductions in depressive or anxious symptoms and enhanced physiological functioning. Likewise, increased mindful awareness may promote coping within the psychological domain, providing a psychospiritual mechanism for enhanced wellbeing. For the most part, we have limited knowledge of how various systems of yoga work. Many traditions of yoga exist, but not all published studies document the tradition employed or provide detailed descriptions of poses used. This lack of information is perhaps one of the more substantial concerns regarding the current standard of yoga research. Without detailed information regarding yoga interventions, replication of findings and an understanding of action on the body and mind is limited. Different traditions of yoga have been likened to different forms of psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral, interpersonal and psychodynamic approaches (Bower et al., 2005). In this sense, not all forms of yoga are interchangeable and some traditions may vary widely in emphasis and approach. This variation may be especially problematic when documenting the physiological and in particular, the metabolic effect of yoga on the body. While some traditions such as Iyengar yoga focus on postural alignment and awareness, a tradition that would theoretically benefit the musculoskeletal and

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

11

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

parasympathetic systems, other traditions such as Ashtanga yoga stress an energetic flow of postures likely associated with short-term autonomic and metabolic activity similar to that seen in other forms of moderate physical activity. Given the possible differential action of these styles of yoga, it is not surprising that conflicting findings exist regarding the physiological effects of yoga practice, particularly the metabolic cost of yoga activity (Clay et al., 2005; Hagins et al., 2007). Future research is required to understand the action of specific styles of yoga, at which point interventions could be designed for specific populations. For example, Iyengar yoga appears to be particularly beneficial for patients with musculoskeletal conditions (Evans, 2008). An additional note regarding the design of yoga interventions concerns potential risk and safety issues. While there is likely to be only minimal risk of adverse events when teachers are sufficiently trained and experienced in working with the population studied, risk of complications is magnified when teachers are not carefully selected. This is particularly the case when working with patient populations who have specific physical and psychological limitations. Interventions with patients require careful assessment and selection of poses and breathing exercises that are part of a clear yogic tradition, and which involve a lineage of teachers to ensure maximal effects for patients and minimization of risk and injury. It is therefore recommended that researchers work with experienced and trained yoga teachers who have in-depth knowledge of the population they are working with. Any publications generated from this research should also include a clear description of poses used, training undertaken by teachers and the tradition of yoga employed. We have explored a number of key benefits underlying the relationship between yoga practice and well-being. However, the empirical evidence remains limited, primarily in methodological design, including small sample sizes, lack of control groups, lack of randomization, and unclear description of what constituted the experimental period or number of sessions. An over-reliance on uncontrolled and non-randomized designs prevents conclusions about the contribution of yoga independent of confounding variables. In addition, much of the empirical yoga literature has emerged from India, and it is unclear to what extent the findings are generalizable to populations in the US and other industrialized countries. Similarly, it is unclear whether research conducted outside India is representative of yoga as it is practiced and known in India. Further research into mechanisms of action is also required. Facilitated dialogue between those versed in yoga and Western medicine and research will enable greater understanding of how yoga may promote health. A number of benefits are expressed in yoga texts, but have yet to be studied scientifically. For example, many purported benefits relate to the action of particular poses, including lymphatic circulation through inversions and modulation of the adrenals

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

12

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

which can be stimulated through backbends and pacified in forward bends (Iyengar, 1966; Iyengar, 2001). However, research has yet to document the effects of specific poses on corresponding physiological systems. The action of inversions on the adrenal system, for example, requires empirical validation. Future research should attempt to integrate yoga theory and the biopsychosocial theory within highly rigorous and well-conducted research studies. Future empirical studies of yoga should incorporate the same stringent research standards as those used in psychological and medical science. Thus, well-designed large RCTs of yoga need to describe attrition rates and adherence in class and home practice, establish intervention details such as total duration, number of sessions per week and length of each session, and the dose required for benefit. The selection and description of appropriate control groups is also necessary. Developing a legitimate sham yoga group has practical and ethical challenges and most RCTs have used a standard care control group. After initial studies have documented the feasibility, safety and preliminary efficacy of yoga for particular conditions, control groups need to account for possible placebo effects related to patient expectations, the social benefits of being in a class and attention from the group facilitator. Although blinding of participants to group status is difficult, ensuring experimenters and raters are unaware of group assignment is necessary. As discussed, additional considerations include identification of the yoga tradition studied, and specification of teacher training and poses used. Yoga is a holistic practice impacting well-being through various systems in a seemingly complex yet integrated manner. Although individual aspects of yoga may prove interesting to study, it is possible that the benefit of yoga is greater than the sum of its physical, psychological and meditative parts. Attempting to reduce benefits to simply stretching limbs, or relaxation techniques may undermine yoga as a complete system for operating on multiple aspects of the person to achieve health and well-being. Moving forward, yoga research should incorporate biological, psychosocial and spiritual outcomes if we are to understand the therapeutic benefits of yoga for medical and healthy populations.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

13

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

References Alter, J. (2004). Yoga in Modern India. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Barnes, P., Powell-Griner, E., McFann, K. & Nahin, R. (2004). CDC Advance data report #343. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults. United States. Bera, T. K. & Rajapurkar, M. V. (1993). Body composition, cardiovascular endurance and anaerobic power of yogic practitioner. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 37(3), 225-8. Bharshankar, J. R., Bharshankar, R. N., Deshpande, V. N., Kaore, S. B. & Gosavi, G. B. (2003). Effect of yoga on cardiovascular system in subjects above 40 years. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 47(2), 202-6. Bijlani, R. L., Vempati, R. P., Yadav, R. K., Ray, R. B., Gupta, V., Sharma, R., Mehta, N. & Mahapatra, S. C. (2005). A brief but comprehensive lifestyle education program based on yoga reduces risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. J Altern Complement Med 11(2), 267-74. Booth-LaForce, C., Thurston, R. C. & Taylor, M. R. (2007). A pilot study of a Hatha yoga treatment for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas 57(3), 286-95. Bose, S., Etta, K. M. & Balagangadharan, S. (1987). The effect of relaxing exercise "shavasan". J Assoc Physicians India 35(5), 365-6. Bower, J. E., Garet, D. & Sternlieb, B. (unpublished manuscript). Iyengar yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Bower, J. E., Woolery, A., Sternlieb, B. & Garet, D. (2005). Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control 12(3), 165-71. Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4), 822-48. Buckelew, S. P., Parker, J. C., Keefe, F. J., Deuser, W. E., Crews, T. M., Conway, R., Kay, D. R. & Hewett, J. E. (1994). Self-efficacy and pain behavior among subjects with fibromyalgia. Pain 59(3), 377-84.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

14

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Bursch, B., Tsao, J. C., Meldrum, M. & Zeltzer, L. K. (2006). Preliminary validation of a self-efficacy scale for child functioning despite chronic pain (child and parent versions). Pain 125(1-2), 35-42. Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Faris, P. & Patel, K. D. (2007). One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun 21(8), 103849. Clay, C. C., Lloyd, L. K., Walker, J. L., Sharp, K. R. & Pankey, R. B. (2005). The metabolic cost of hatha yoga. J Strength Cond Res 19(3), 604-10. Dash, M. & Telles, S. (2001). Improvement in hand grip strength in normal volunteers and rheumatoid arthritis patients following yoga training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 45(3), 355-60. DiBenedetto, M., Innes, K. E., Taylor, A. G., Rodeheaver, P. F., Boxer, J. A., Wright, H. J. & Kerrigan, D. C. (2005). Effect of a gentle Iyengar yoga program on gait in the elderly: an exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86(9), 1830-7. DiStasio, S. A. (2008). Integrating yoga into cancer care. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12(1), 125-30. Drossaers-Bakker, K. W., de Buck, M., van Zeben, D., Zwinderman, A. H., Breedveld, F. C. & Hazes, J. M. (1999). Long-term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum 42(9), 1854-60. Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196, 129-36. Escalante, A. & del Rincon, I. (1999). How much disability in rheumatoid arthritis is explained by rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum 42(8), 171221. Evans, S., Subramanian, S. & Sternlieb, B. (2008). Yoga as treatment for chronic pain conditions: a literature review. International Journal on Disability and Human Development 7(1), 25-32.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

15

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Fletcher, L. & Hayes, S. C. (2005). Relational frame theory, acceptance and commitment therapy and a functional analytic definition of mindfulness. J Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 23, 315-36. Garfinkel, M. S., Schumacher, H. R., Husain, A., Levy, M. & Reshetar, R. A. (1994). Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol 21(12), 2341-3. Garfinkel, M. S., Singhal, A., Katz, W. A., Allan, D. A., Reshetar, R. & Schumacher, H. R., Jr. (1998). Yoga-based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized trial. Jama 280(18), 1601-3. Gatchel, R. J., Peng, Y. B., Peters, M. L., Fuchs, P. N. & Turk, D. C. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 133(4), 581-624. Granath, J., Ingvarsson, S., von Thiele, U. & Lundberg, U. (2006). Stress management: a randomized study of cognitive behavioural therapy and yoga. Cogn Behav Ther 35(1), 3-10. Greendale, G. A., McDivit, A., Carpenter, A., Seeger, L. & Huang, M. H. (2002). Yoga for women with hyperkyphosis: results of a pilot study. Am J Public Health 92(10), 1611-4. Greenwood, B. N. & Fleshner, M. (2008). Exercise, learned helplessness, and the stress-resistant brain. Neuromolecular Med (10), 81-98. Haaz, S. (2007). Yoga for people with arthritis. http://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/patient-corner/disease-management/yoga.html. Hagins, M., Moore, W. & Rundle, A. (2007). Does practicing hatha yoga satisfy recommendations for intensity of physical activity which improves and maintains health and cardiovascular fitness? BMC Complement Altern Med 7, 40. Harinath, K., Malhotra, A. S., Pal, K., Prasad, R., Kumar, R., Kain, T. C., Rai, L. & Sawhney, R. C. (2004). Effects of Hatha yoga and Omkar meditation on cardiorespiratory performance, psychologic profile, and melatonin secretion. J Altern Complement Med 10(2), 261-8.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

16

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Haslock, I., Monro, R., Nagarathna, R., Nagendra, H. R. & Raghuram, N. V. (1994). Measuring the effects of yoga in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 33(8), 787-8. Iyengar, B. (1966). Light on Yoga. New York: Schocken Books. Iyengar, B. (2001). The Path to Holistic Health. Dorling Kindersley. John, P. J., Sharma, N., Sharma, C. M. & Kankane, A. (2007). Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: a randomized controlled trial. Headache 47(5), 654-61. Kaliappan, L. K., K.V. (1992). Efficacy of yoga therapy in the management of headaches. Journal of Indian Psychology 10(1 & 2), 41-7. Kamei, T., Toriumi, Y., Kimura, H., Ohno, S., Kumano, H. & Kimura, K. (2000). Decrease in serum cortisol during yoga exercise is correlated with alpha wave activation. Percept Mot Skills 90(3 Pt 1), 1027-32. Kerman, I. A. (2008). Organization of brain somatomotor-sympathetic circuits. Exp Brain Res 187(1), 1-16. Khalsa, H. K. (2003). Yoga: an adjunct to infertility treatment. Fertil Steril 80 Suppl 4, 46-51. Khalsa, S. B. (2004). Treatment of chronic insomnia with yoga: a preliminary study with sleep-wake diaries. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 29(4), 269-78. Khatri, D., Mathur, K. C., Gahlot, S., Jain, S. & Agrawal, R. P. (2007). Effects of yoga and meditation on clinical and biochemical parameters of metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 78(3), e9-10. Khattab, K., Khattab, A. A., Ortak, J., Richardt, G. & Bonnemeier, H. (2007). Iyengar yoga increases cardiac parasympathetic nervous modulation among healthy yoga practitioners. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 4(4), 511-7. Kirkwood, G., Rampes, H., Tuffrey, V., Richardson, J. & Pilkington, K. (2005). Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. Br J Sports Med 39(12), 884-91.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

17

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Kolasinski, S. L., Garfinkel, M., Tsai, A. G., Matz, W., Van Dyke, A. & Schumacher, H. R. (2005). Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 11(4), 689-93. Kuttner, L., Chambers, C. T., Hardial, J., Israel, D. M., Jacobson, K. & Evans, K. (2006). A randomized trial of yoga for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome. Pain Res Manag 11(4), 217-23. Lee, S. W., Mancuso, C. A. & Charlson, M. E. (2004). Prospective study of new participants in a community-based mind-body training program. J Gen Intern Med 19(7), 760-5. Lehrer, P., Sasaki, Y. & Saito, Y. (1999). Zazen and cardiac variability. Psychosom Med 61(6), 812-21. Low, C. A., Stanton, A. L. & Danoff-Burg, S. (2006). Expressive disclosure and benefit finding among breast cancer patients: mechanisms for positive health effects. Health Psychol 25(2), 181-9. Manjunath, N. K. & Telles, S. (2005). Influence of Yoga and Ayurveda on selfrated sleep in a geriatric population. Indian J Med Res 121(5), 683-90. Mason, V. L., Mathias, B. & Skevington, S. M. (2008). Accepting low back pain: is it related to a good quality of life? Clin J Pain 24(1), 22-9. McBrien, B. (2006). A concept analysis of spirituality. Br J Nurs 15(1), 42-5. McCaffrey, R., Ruknui, P., Hatthakit, U. & Kasetsomboon, P. (2005). The effects of yoga on hypertensive persons in Thailand. Holist Nurs Pract 19(4), 173-80. Mehta, S., Mehta, M., & Mehta, S. (2006). Yoga The Iyengar Way. New York: Alfred Knopf. Moadel, A. B., Shah, C., Wylie-Rosett, J., Harris, M. S., Patel, S. R., Hall, C. B. & Sparano, J. A. (2007). Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol 25(28), 4387-95.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

18

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Monro, R., Nagarathna, R. & Nagendra, H.R. (1995). Yoga for common ailments. New York/London: Simon & Schuster. Netz, Y. & Lidor, R. (2003). Mood alterations in mindful versus aerobic exercise modes. J Psychol 137(5), 405-19. Oken, B. S., Kishiyama, S., Zajdel, D., Bourdette, D., Carlsen, J., Haas, M., Hugos, C., Kraemer, D. F., Lawrence, J. & Mass, M. (2004). Randomized controlled trial of yoga and exercise in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 62(11), 2058-64. Pansare, M. S., Kulkarni, A. N. & Pendse, U. B. (1989). Effect of yogic training on serum LDH levels. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 29(2), 177-8. Pilkington, K., Kirkwood, G., Rampes, H. & Richardson, J. (2005). Yoga for depression: the research evidence. J Affect Disord 89(1-3), 13-24. Prakash, S., Meshram, S. & Ramtekkar, U. (2007). Athletes, yogis and individuals with sedentary lifestyles; do their lung functions differ? Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 51(1), 76-80. Raub, J. A. (2002). Psychophysiologic effects of Hatha Yoga on musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary function: a literature review. J Altern Complement Med 8(6), 797-812. Riley, D. (2004). Hatha yoga and the treatment of illness. Altern Ther Health Med 10(2), 20-1. Sarang, P., Telles., S. (2006). Effects of two yoga based relaxation techniques on heart rate variability. International Journal of Stress Management 13(4), 460-75. Sathyaprabha, T. N., Satishchandra, P., Pradhan, C., Sinha, S., Kaveri, B., Thennarasu, K., Murthy, B. T. & Raju, T. R. (2008). Modulation of cardiac autonomic balance with adjuvant yoga therapy in patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 12(2), 245-52. Schanberg, L. E., Lefebvre, J. C., Keefe, F. J., Kredich, D. W. & Gil, K. M. (1997). Pain coping and the pain experience in children with juvenile chronic arthritis. Pain 73(2), 181-9.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

19

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Schell, F. J., Allolio, B. & Schonecke, O. W. (1994). Physiological and psychological effects of Hatha-Yoga exercise in healthy women. Int J Psychosom 41(1-4), 46-52. Sears, S. R., Stanton, A. L. & Danoff-Burg, S. (2003). The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 22(5), 487-97. Sessanna, L., Finnell, D. & Jezewski, M. A. (2007). Spirituality in nursing and health-related literature: a concept analysis. J Holist Nurs 25(4), 252-62; discussion 63-4. Shapiro, D., Cook, I. A., Davydov, D. M., Ottaviani, C., Leuchter, A. F. & Abrams, M. (2007). Yoga as a complementary treatment of depression: effects of traits and moods on treatment outcome. Advance Access eCAM, 1-10. Sinha, B., Ray, U. S., Pathak, A. & Selvamurthy, W. (2004). Energy cost and cardiorespiratory changes during the practice of Surya Namaskar. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 48(2), 184-90. Sivasankaran, S., Pollard-Quintner, S., Sachdeva, R., Pugeda, J., Hoq, S. M. & Zarich, S. W. (2006). The effect of a six-week program of yoga and meditation on brachial artery reactivity: do psychosocial interventions affect vascular tone? Clin Cardiol 29(9), 393-8. Spicuzza, L., Gabutti, A., Porta, C., Montano, N. & Bernardi, L. (2000). Yoga and chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Lancet 356(9240), 1495-6. Streeter, C. C., Jensen, J. E., Perlmutter, R. M., Cabral, H. J., Tian, H., Terhune, D. B., Ciraulo, D. A. & Renshaw, P. F. (2007). Yoga Asana sessions increase brain GABA levels: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 13(4), 419-26. Taimni, L. (1961). The science of yoga. Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

20

Evans et al.: Action of Yoga on Health

Telles, S., Joshi, M., Dash, M., Raghuraj, P., Naveen, K. V. & Nagendra, H. R. (2004). An evaluation of the ability to voluntarily reduce the heart rate after a month of yoga practice. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 39(2), 119-25. Telles, S., Naveen, K. V. & Dash, M. (2007). Yoga reduces symptoms of distress in tsunami survivors in the andaman islands. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 4(4), 503-9. Tooley, G. A., Armstrong, S. M., Norman, T. R. & Sali, A. (2000). Acute increases in night-time plasma melatonin levels following a period of meditation. Biol Psychol 53(1), 69-78. Tsao, J. C. I., Meldrum, M., Kim, S . C., Jacob, M. C. & Zeltzer, L. K. (2007). Treatment preferences for CAM in pediatric chronic pain patients. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. Vahia, N. S., Vinekar, S. L. & Doongaji, D. R. (1966). Some ancient Indian concepts in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 112(492), 1089-96. Vedamurthachar, A., Janakiramaiah, N., Hegde, J. M., Shetty, T. K., Subbakrishna, D. K., Sureshbabu, S. V. & Gangadhar, B. N. (2006). Antidepressant efficacy and hormonal effects of Sudarshana Kriya Yoga (SKY) in alcohol dependent individuals. J Affect Disord 94(1-3), 249-53. Waelde, L. C., Thompson, L. & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2004). A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol 60(6), 677-87. Weinberger, M., Tierney, W. M., Booher, P. & Hiner, S. L. (1990). Social support, stress and functional status in patients with osteoarthritis. Soc Sci Med 30(4), 503-8. West, J., Otte, C., Geher, K., Johnson, J. & Mohr, D. C. (2004). Effects of Hatha yoga and African dance on perceived stress, affect, and salivary cortisol. Ann Behav Med 28(2), 114-8. Whitford, H. S., Olver, I. N. & Peterson, M. J. (2008). Spirituality as a core domain in the assessment of quality of life in oncology. Psychooncology, 17(11), 1121-1128.

Published by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2009

21

Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Vol. 6 [2009], Iss. 1, Art. 15

Williams, K. A., Petronis, J., Smith, D., Goodrich, D., Wu, J., Ravi, N., Doyle, E. J., Jr., Gregory Juckett, R., Munoz Kolar, M., Gross, R. & Steinberg, L. (2005). Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain 115(1-2), 107-17. Woolery, A., Myers, H., Sternlieb, B. & Zeltzer, L. (2004). A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern Ther Health Med 10(2), 60-3. Yurtkuran, M., Alp, A., Yurtkuran, M. & Dilek, K. (2007). A modified yogabased exercise program in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med 15(3), 164-71.

http://www.bepress.com/jcim/vol6/iss1/15 DOI: 10.2202/1553-3840.1183

22

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- FINDING ONESELF - EditedDocument5 pagesFINDING ONESELF - Editedrexy moseNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Module 11: Behavioral Activation: ObjectivesDocument6 pagesModule 11: Behavioral Activation: ObjectivesMaria BagourdiNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- A Comparative Study On Anxiety Among College Students From Rural and Urban AreasDocument8 pagesA Comparative Study On Anxiety Among College Students From Rural and Urban AreasAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Learning Organisations: Presentation FOR ALL Who Want To LearnDocument35 pagesLearning Organisations: Presentation FOR ALL Who Want To Learnmengesha abyeNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Zulfatul Faizah-0402518022 - EthnoscienceDocument10 pagesZulfatul Faizah-0402518022 - EthnoscienceArief Budhiman d'KenkyuuNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Dream Work of Sigmund Freud: John Shannon HendrixDocument32 pagesThe Dream Work of Sigmund Freud: John Shannon Hendrixdr_tusharbNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- First Draft SleepingDocument3 pagesFirst Draft Sleepingapi-581677767No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Nursing Science and Profession: As An ArtDocument45 pagesNursing Science and Profession: As An ArtHans TrishaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- 4.UCSP. Q1.Week 4 Culture Social Pattern Ethnocentrism RelativismDocument14 pages4.UCSP. Q1.Week 4 Culture Social Pattern Ethnocentrism Relativismjoel100% (2)

- 74 76communication BarriersDocument4 pages74 76communication BarrierscpayagNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Chapter 15Document5 pagesChapter 15Orlino PeterNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Task A2Document3 pagesTask A2api-258745500No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Conceptualizing Content and Developing MaterialsDocument3 pagesConceptualizing Content and Developing MaterialsAbim AbdiNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Timothy Freke - Lucid LivingDocument22 pagesTimothy Freke - Lucid Livingcybhert100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Employee Performance Management Group Project (Finalized)Document50 pagesEmployee Performance Management Group Project (Finalized)Kauthamen AppuNo ratings yet

- Eline de Vries-Van Ketel: How Assortment Variety AffectsDocument15 pagesEline de Vries-Van Ketel: How Assortment Variety AffectsrenzeiaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Characteristicsof Quantitative ResearchDocument12 pagesCharacteristicsof Quantitative ResearchGladys Glo MarceloNo ratings yet

- 9 Task AnalysisDocument3 pages9 Task Analysisapi-508725671100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- GE6 Lesson 1-Art AppreciationDocument3 pagesGE6 Lesson 1-Art AppreciationNiña Amato100% (1)

- Ge2021 PeeDocument122 pagesGe2021 PeeaassaanmkNo ratings yet

- Usc Recommendation FormDocument3 pagesUsc Recommendation FormEARL JOHN A BESARIONo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson 3 - Culture in Moral BehaviorDocument8 pagesLesson 3 - Culture in Moral BehaviorMark Louie RamirezNo ratings yet

- Essay 2Document8 pagesEssay 2booksrcooltouknowNo ratings yet

- Handout - Creating Sales MAGICDocument16 pagesHandout - Creating Sales MAGICGlodhakKaosNo ratings yet

- El Sentimiento de SoledadDocument13 pagesEl Sentimiento de SoledadSand SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Social Studies ECE - Module 6 - FinalsDocument5 pagesSocial Studies ECE - Module 6 - FinalsLea May EnteroNo ratings yet

- Adorno KierkegaardDocument21 pagesAdorno KierkegaardMax777No ratings yet

- The Giant's StewDocument3 pagesThe Giant's Stewapi-479524591No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Article in Assessing Young ChildrenDocument2 pagesArticle in Assessing Young ChildrenAnjhenie BalestramonNo ratings yet

- Anabolic Optimism PDFDocument42 pagesAnabolic Optimism PDFcomtrol100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)