Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bolden - Distributed Leadership PDF

Uploaded by

aolmedoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bolden - Distributed Leadership PDF

Uploaded by

aolmedoCopyright:

Available Formats

DISTRIBUTED LEADERSHIP1 Richard Bolden

University of Exeter Discussion Papers in Management Paper number 07/02 ISSN 1472 2939

Due to be published in Marturano, A. and Gosling, J. (eds) (2007) Leadership, The Key

Concepts, Abingdon: Routledge. Publication scheduled for September 2007.

-1-

DISTRIBUTED LEADERSHIP Richard Bolden The concept of distributed leadership has become popular in recent years as an alternative to models of leadership that concern themselves primarily with the attributes and behaviours of individual leaders (e.g. trait, situational , style and transformational theories). This approach argues for a more systemic perspective, whereby leadership responsibility is dissociated from formal organisational roles, and the action and influence of people at all levels is recognised as integral to the overall direction and functioning of the organisation. Spillane (2006) suggests that a distributed perspective puts leadership practice centre stage (p. 25) thereby encouraging a shift in focus from the traits and characteristics of leaders to the shared activities and functions of leadership.

The call for a more collectively-embedded notion of leadership has arisen from research, theory and practice that highlights the limitations of the traditional leader-follower dualism that places the responsibility for leadership firmly in the hands of the leader and represents the follower as somewhat passive and subservient. Instead, it is argued that: leadership is probably best conceived as a group quality, as a set of functions which must be carried out by the group (Gibb, 1954, cited in Gronn 2000: 324). As such, this approach demands a dramatic reconsideration of the distribution of power and influence within organisations. It isnt simply about creating more leaders (a numerical/additive function) but

-2-

facilitating concertive action and pluralistic engagement (Gronn, 2000; 2002). In effect, distributed leadership is far more than the sum of its parts.

That said, distributed leadership does not deny the key role played by people in formal leadership positions, but proposes that this is only the tip of the iceberg. Spillane et al. (2004: 5) argue that leadership is stretched over the social and situational contexts of the organisation and extend the notion to include material and cultural artefacts (language, organisational systems, physical environment, etc.). The situated nature of leadership is viewed as constitutive of leadership practice (ibid, p.20-21) and hence demands recognition of leadership acts within their wider context.

Such a perspective draws heavily on systems and process theory and locates leadership clearly beyond the individual leader and within the relationships and interactions of multiple actors and the situations in which they find themselves. A useful analogy is given by Wilfred Drath in his book The Deep Blue Sea (2002) where he urges us look beyond the wave crests (formal leaders) to the deep blue sea from whence they come (the latent leadership potential within the organisation).

In a review of the literature Bennet et al. (2003) suggest that, despite some variations in definition, distributed leadership is based on three main premises:

-3-

firstly that leadership is an emergent property of a group or network of interacting individuals; secondly that there is openness to the boundaries of leadership (i.e. who has a part to play both within and beyond the organisation); and thirdly, that varieties of expertise are distributed across the many, not the few. distributed leadership is represented as dynamic, relational, Thus,

inclusive,

collaborative and contextually-situated. It requires a system-wide perspective that not only transcends organisational levels and roles but also organisational boundaries. Thus, for example, in the field of education, where distributed

leadership is being actively promoted, one might consider the contribution of parents, students and the local community as well as teachers and governors in school leadership.

Taking this view, leadership is about learning together and constructing meaning and knowledge collectively and collaboratively. It involves opportunities to surface and mediate perceptions, values, beliefs, information and assumptions through continuing conversations. It means generating ideas together; seeking to reflect upon and make sense of work in the light of shared beliefs and new information; and creating actions that grow out of these new understandings. It implies that leadership is socially constructed and culturally sensitive. It does not imply a leader/follower divide, neither does it point towards the leadership potential of just one person. (Harris, 2003: 314)

-4-

In addition to extending the boundaries of leadership the above quote indicates the centrality of dialogue and the construction of shared meaning within social groups. As such, the concept has much in common with notions of democratic and inclusive leadership (Woods, 2004).

Of the authors who have attempted to develop a conceptual model of distributed leadership Gronn (2000, 2002) and Spillane et al. (2004) are perhaps the most comprehensive. In each case, they have used Activity Theory (Engestrom, 1999) as a theoretical tool to frame the idea of distributed leadership practice, using it as a bridge between agency and structure (in Gronns case) and distributed cognition and action (in Spillane et als case). Leadership, therefore, is seen an integral part of the daily activities and interactions of everyone across the enterprise, irrespective of position. It is revealed equally within small, incremental, informal and emergent acts as within large-scale transformational change from the top. The more members across the organization exercise their influence, the greater the leadership distribution. This is not a zero sum equation where developing the agency of followers diminishes the power of formal leaders but one where each can mutually reinforce the other.

In practice, there are many forms that distributed leadership can take and the literature does not generally prescribe one over the other. Within schools, for

-5-

example, MacBeath (2005) identifies six forms of distributed leadership (formal, pragmatic, strategic, incremental, opportunistic and cultural) but argues that the most appropriate and effective form will depend upon the situation. There are, however, some serious challenges to the practical implementation of distributed leadership. MacBeath (ibid) argues that distributed leadership is premised on trust, implies a mutual acceptance of one anothers leadership potential, requires formal leaders to let go some of their control and authority, and favours consultation and consensus over command and control. Each of these poses a serious challenge to traditional hierarchical models of authority and control in organisations and can place severe physical and psychological demands on designated managers.

There are also serious implications for leadership development. Whilst the majority of investment continues to be for individuals in formal leadership roles, a distributed perspective would argue for the development of leadership capacity throughout the organisation. This distinction is captured by Day (2001) in his comparison between leader and leadership development. Whereas leader development is an investment in human capital to enhance intrapersonal competence for selected individuals, leadership development is an investment in social capital to develop interpersonal networks and cooperation within organisations and other social systems. In his account both of these are necessary but the latter is all too often neglected.

-6-

By considering leadership practice as both thinking and activity that emerges in the execution of leadership tasks in and through the interaction of leaders, followers and situation (Spillane et al., 2004: 27) distributed leadership offers a powerful post-heroic representation of leadership well suited to complex, changing and inter-dependent environments. The challenge will be whether or not organisations and the holders of power will be sufficiently flexible to enable this to occur in practice.

References Bennett, N., Wise, C., Woods, P. and Harvey, J. (2003) Distributed Leadership. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership. Day, D. (2001) Leadership development: a review in context, Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581-613. Drath, W. (2001) The Deep Blue Sea: Rethinking the Source of Leadership. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass. Engestrom, Y. (1999) Activity theory and individual and social transformation, in Y. Engestrom, R. Miettinen and R-L. Punamaki (eds) Perspectives on activity theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gibb, C. A. (1954) Leadership, in G. Lindzey (ed.) Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 2, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, pp. 877917. Gronn, P. (2000) Distributed properties: a new architecture for leadership, Educational Management and Administration, 28(3), 317-338.

-7-

Gronn, P. (2002) Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis, Leadership Quarterly, 13, 423-451. Harris, A. (2003) Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: heresy, fantasy or possibility? School Leadership and Management, 23 (3), 313-324. MacBeath, J. (2005) Leadership as distributed: a matter of practice, School Leadership and Management, 25(4), 349-66. Spillane, J.P. (2006) Distributed Leadership, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Spillane, J.P., Halverson, R. and Diamond, J.B. (2004) Towards a theory of leadership practice: a distributed perspective, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3-34. Woods, P.A. (2004) Democratic leadership: drawing distinctions with distributed leadership, International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(1), 3-26.

Biography Richard Bolden is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter, UK. His current research explores the interface and

interplay between individual and collective approaches to leadership and leadership development and how they contribute towards social change. [Email: Richard.Bolden@exeter.ac.uk].

Printed: 13 August 2007

-8-

You might also like

- Conley - A Different Definition of Success - Micro Cornucopia Interview - 1989 PDFDocument4 pagesConley - A Different Definition of Success - Micro Cornucopia Interview - 1989 PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Parable of The TalentsDocument65 pagesParable of The Talentsaolmedo100% (1)

- Theological Blogging: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Blogging and TheologyDocument33 pagesTheological Blogging: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Blogging and TheologyaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Estes SimChurch Review PDFDocument6 pagesEstes SimChurch Review PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Estes SimChurch Review PDFDocument6 pagesEstes SimChurch Review PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Theological Blogging: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Blogging and TheologyDocument33 pagesTheological Blogging: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Blogging and TheologyaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Estes SimChurch Review PDFDocument6 pagesEstes SimChurch Review PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - What Is Leadership PDFDocument38 pagesBolden - What Is Leadership PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - The Shadow Side of Leadership PDFDocument4 pagesBolden - The Shadow Side of Leadership PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - The Shadow Side of Leadership PDFDocument4 pagesBolden - The Shadow Side of Leadership PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - Trends and Perspectives in Management and Leadership Development PDFDocument13 pagesBolden - Trends and Perspectives in Management and Leadership Development PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - Leadership Competencies. Time To Change The Tune PDFDocument19 pagesBolden - Leadership Competencies. Time To Change The Tune PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - Trends and Perspectives in Management and Leadership Development PDFDocument13 pagesBolden - Trends and Perspectives in Management and Leadership Development PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Bolden - From Leaders To Leadership PDFDocument9 pagesBolden - From Leaders To Leadership PDFaolmedoNo ratings yet

- Leadership Theory PDFDocument44 pagesLeadership Theory PDFsandeep tokas100% (1)

- As You Go. John Howard Yoder As A Mission TheologianDocument20 pagesAs You Go. John Howard Yoder As A Mission TheologianaolmedoNo ratings yet

- The Social Scientific Study of Leadership: Quo Vadis?Document65 pagesThe Social Scientific Study of Leadership: Quo Vadis?aolmedoNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Charismatic LeadershipDocument9 pagesThe Dark Side of Charismatic LeadershipaolmedoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ELL on Kpop Stan Twitter: Schematic Learning of Memetic DiscourseDocument22 pagesELL on Kpop Stan Twitter: Schematic Learning of Memetic DiscoursePutu Febby Liana AnggitasariNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelligences TheoryDocument18 pagesMultiple Intelligences TheorySameera DalviNo ratings yet

- HistorylessonplansDocument27 pagesHistorylessonplansapi-420935597No ratings yet

- Design Methodology - Kinetic Architecture-LibreDocument182 pagesDesign Methodology - Kinetic Architecture-LibreMînecan Ioan AlexandruNo ratings yet

- BDBB4103 Introductory Human Resource Development - Cdec19Document223 pagesBDBB4103 Introductory Human Resource Development - Cdec19Ruby limNo ratings yet

- Tamil Language Rights in Sri Lanka - English VersionDocument78 pagesTamil Language Rights in Sri Lanka - English VersionSanjana HattotuwaNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Core Subject: Topic/Lesson Name Content Standards Performance Standards Learning CompetenciesDocument4 pagesSenior High School Core Subject: Topic/Lesson Name Content Standards Performance Standards Learning CompetenciesRegean Ellorimo100% (1)

- The Ten Benedictine Hallmarks: ConversatioDocument2 pagesThe Ten Benedictine Hallmarks: ConversatioLouis MalaybalayNo ratings yet

- Smith - A Place Called Irony (Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong)Document6 pagesSmith - A Place Called Irony (Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong)Paul GuillenNo ratings yet

- Glenn Webster Manifesto OMDocument4 pagesGlenn Webster Manifesto OMGlenn Mac An FhíodóirNo ratings yet

- Pedoman & (Contoh Paper) Tugas Uas HTNDocument18 pagesPedoman & (Contoh Paper) Tugas Uas HTNRaafi Rahman100% (1)

- Titus Hjelm-Is God Back - Reconsidering The New Visibility of Religion-Bloomsbury Academic (2015)Document297 pagesTitus Hjelm-Is God Back - Reconsidering The New Visibility of Religion-Bloomsbury Academic (2015)Johnny Tapu100% (2)

- DRDO Recruitment 2023 2Document1 pageDRDO Recruitment 2023 2Munshi KamrulNo ratings yet

- Mind MoviesDocument1 pageMind Moviesduxonb5661No ratings yet

- Cchms Sec 3el Mye Paper 2 (Sections A B)Document6 pagesCchms Sec 3el Mye Paper 2 (Sections A B)Samy RajooNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Level of Consciousness: Application To Nursing PracticeDocument5 pagesKnowledge and Level of Consciousness: Application To Nursing PracticernrmmanphdNo ratings yet

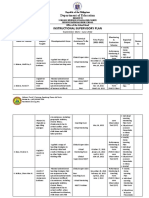

- Philippine Education Dept Instructional PlanDocument9 pagesPhilippine Education Dept Instructional PlanIVY HISONo ratings yet

- Derivatives Markets 3rd Edition McDonald Test Bank 1Document26 pagesDerivatives Markets 3rd Edition McDonald Test Bank 1gracegreenegrsqdixozy100% (22)

- Maya Angelou AssignmentDocument4 pagesMaya Angelou AssignmentLucifur KingNo ratings yet

- KPF Resume 2020Document2 pagesKPF Resume 2020api-506356996No ratings yet

- Informal Learning at Workplace and Work Environment A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesInformal Learning at Workplace and Work Environment A Literature Reviewarcherselevators100% (1)

- Tekton Issue 3 Final March 2015Document8 pagesTekton Issue 3 Final March 2015Alden CayagaNo ratings yet

- ED416991Document23 pagesED416991Kasiana ElenaNo ratings yet

- Cultural Erasure, Retention and Renewal SEDocument20 pagesCultural Erasure, Retention and Renewal SELeondreNo ratings yet

- Yoga Link 1206Document44 pagesYoga Link 1206princegirishNo ratings yet

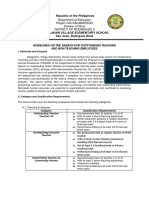

- School Based Guidelines On The Search For Outstanding Teaching and Non Teaching PersonnelDocument6 pagesSchool Based Guidelines On The Search For Outstanding Teaching and Non Teaching PersonnelGina Montano100% (6)

- Toba Tek Singh 22-06-11Document65 pagesToba Tek Singh 22-06-11arslanengNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Taboos in Igbo SocietyDocument17 pagesLinguistic Taboos in Igbo SocietyPetit BbyNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Rural Urban Fringe of Jammu City IndiaDocument9 pagesCharacteristics of Rural Urban Fringe of Jammu City IndiaShubhaiyu ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Module 3A Designing Instruction in The Different Learning Delivery ModalitiesDocument58 pagesModule 3A Designing Instruction in The Different Learning Delivery Modalitiesanon_455551365100% (2)