Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DSFSFS

Uploaded by

Samar SinghCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DSFSFS

Uploaded by

Samar SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

BOOK REVIEW

A Valuable Collection on the Indian Economy

Arvind Subramanian

there was a lot of variation within India, geographically and temporally, in terms of development outcomes. On Healthcare One of the very best contributions in the handbook is that by Jishnu Das and Jeffrey Hammer on healthcare and health policy. The authors begin by citing the striking data about Indias poor showing on health indicators, even allowing for Indias level of development, and then describe stories of two preventable deaths. They then go on to present compelling evidence to make the case that the healthcare debate has focused too much on access to healthcare and too little on its quality. In the process, they debunk three myths: that the poor do not have access to care; that private sector doctors are crooks and quacks; and that creating the infrastructure and providing training are the solution. The depressing conclusion is that the attitudes of those who receive healthcare patients and those who provide it may need to be changed if serious improvements in health outcomes are to be achieved in India. This is not the rst time or the only place where the authors have made these arguments but the handbook is elevated and made relevant by contributions such as these.

31

ndia has turned from being a development failure to a place of development possibilities (it is still far from being a development success). To mark this transition, Chetan Ghate, of the Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi, collaborating with Oxford University Press, has painstakingly and impressively put together a collection of 31 academic and policy essays on Indias economic development. The Oxford Handbook that contains them will adorn many a bookshelf and library. Ghate deserves kudos for providing what is really an intellectual public good (which is always undersupplied) for scholarship on Indian economic development. This reader neither has the breadth of expertise nor is the audience captive enough for this review to discuss all the contributions in this handbook; and comprehensiveness is one of its virtues. The essays are organised under seven broad headings: history, poverty, industrialisation, social infrastructure, politics,

EPW

The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Economy edited by Chetan Ghate (New Delhi: Oxford University Press), 2012; pp 984, Rs 4,995 (hardback).

macroeconomics, and the external sector. Unsurprisingly, there is some repetition and the essays are of varying quality, length, focus and analytical sophistication. For sure, not all essays will have the same shelf life. Before getting to the charges of omission and commission I want to discuss, albeit selectively, some of the contributions to the handbook. The handbook begins with great promise with the essay on Indias economy in the 200 years preceding Independence. With remarkable succinctness, the author describes broad economic trends during this period. The still-persistent effects of colonial rule are well known by now. But the essay concludes with the important observation somewhat objectionable to hardcore nationalists that colonalism could not have been uniformly negative because

vol xlviII no 5

Economic & Political Weekly

february 2, 2013

BOOK REVIEW

Another thoughtful essay is by Willem Buiter and Urjit Patel on scal rules in India. This essay seems particularly topical given the state of Indias scal nances, characterised by large and rising decits despite rapid growth. It outlines very lucidly why debt and decits matter and then examines scal performance in India. The sobering message of this essay is that scal rules cannot succeed unless they are designed in a way that is incentive-compatible, that is unless there are in-built incentives for the central and state governments to adhere to the rules. But that is not easy to do. The essay could have probed to a greater extent the political economy of scal policy. For example, what are the political interests and coalitions supporting subsidies? Can exogenous developments help break them down? Alternatively, is there hope for more prudent policies if cash-based transfers can substitute for subsidies? Dated Treatment The essay on the globalisation debate in India covers the ground well but seems a bit dated. To this reader, one really interesting fact was the lack of a protectionist or dirigiste response in India in the wake of the global nancial crises. Around the world, there is increasing scepticism about nancial globalisation but in India capital account liberalisation has been accelerated after the crisis. Even in China there is a move back towards state capitalism whereas in India the objective if not the practice is one of reduced state involvement in the economy. A fuller discussion of these contrasting responses would have been welcome. The essay on caste and mobility by Vegard and Iversen struck this reader as more pessimistic than warranted by the recent research of Kapur et al (2010) who show dramatic improvements not just in the economic situation of dalits but in their social status. Indeed Kapur et al (2010) and some ongoing research by them portray the achievements of the dalits in the reform era as truly radical and comparable to the breakdown of feudalism in Europe several centuries before. This sort of dissonance between Vegard and Iversen versus Kapur et al

Economic & Political Weekly EPW

(2010) is to some extent unavoidable because diversity is if anything the stuff of academic inquiry. Nevertheless one does wonder: would any reader of this Handbook come away with the correct impressions about Indias economic and social development? Perhaps that is not a fair question to ask but there is an interesting question as to the responsibilities that come with creating a handbook as opposed to compiling any run-of-the-mill collection of essays and papers. Some essays suffer unduly from taking the approach of covering all bases at the expense of providing sharp insights/ perspectives and/or drawing sharp conclusions. The essays on primary education, on higher education and on the dynamics of Indias economic reforms fall into this category. For example, in the latter, there is a listing of all the challenges faced by India from taxes to governance to public service delivery to land markets to competition policy, and all spelt out in less than a page: this is useful but whether our understanding of any of the challenges is deepened is an open question. The discussion of higher education seemed to overlook the key challenge posed by the globalisation of talent for creating an effective system of higher education. Serious Omissions There are also some serious omissions. For example, ination which has, over the last few years, become a rst-order macroeconomic problem for India does not get serious, if any, attention in this handbook. That omission can be explained perhaps by timing and the life cycle of a project such as this. When the papers were commissioned presumably towards the end of the last decade ination had not reared its head at least as a persistent phenomenon and one that has proven unamenable to policy action. More puzzling is the neglect of what is Indias biggest development challenge, namely, the decline of public institutions and state capacity. There is a chapter on corruption and references littered throughout the volume on institutions and politics but no serious grappling with the quality of basic institutions such as the bureaucracy, police, judiciary, and military which seem to be in serious

vol xlviII no 5

decline. One could argue that the difference between the performance of China and India is not their reliance on markets but in the basic capacity of their respective governments to deliver basic services and build infrastructure. This issue deser ved a lot more attention than the handbook has devoted. In terms of inequality, while the handbook has covered all the basic ground, it might have been more interesting and forward-looking to have paid particular attention to the Maoists and the Muslims. Caste is arguably becoming the less important axis of cleavage and inequality compared to others. The tribals in the forested parts of India have been excluded not just by the reform process but from participation in the market economy. Why and how might this be rectied? Similarly, can the insufcient advancement of Muslims be explained by discrimination against them or are other factors at play? The more basic, even philosophical, questions that crossed this readers mind when going through this volume related to the purpose of a handbook: should it be to assemble research conducted at a point in time or should it be a guide to the essential, even canonical, readings on the various topics, some of which take the form of sharp analytical surveys or reviews? Oxford University Press and Ghate have opted for the former. It is an open question whether the latter approach adopted for example in the early Handbooks of Development and International Economics might have assured a longer shelf life. Regardless, this handbook will be a valuable contribution.

Arvind Subramanian (ASubramanian@ piie.com) is at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Center for Global Development, Washington DC.

Reference

Devesh Kapur, Chandra Bhan Prasad, Lant Pritchett, D Shyam Babu (2010): Rethinking Inequality: Dalits in Uttar Pradesh in the Market Reform Era, Economic & Political Weekly, 28 August, Vol XLV, No 35.

Notice to Subscribers

The RBI has issued a guideline stating that only CTS2010 cheques will be cleared from January 1, 2013. We request all our subscribers to send us CTS-2010 standard cheques.

february 2, 2013

33

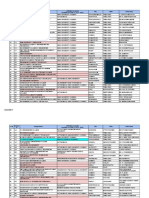

You might also like

- Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 1 (1988)Document845 pagesHandbook of Development Economics, Vol. 1 (1988)nur hasanah100% (2)

- CBSE School CodesDocument145 pagesCBSE School CodesAnas Ahmad50% (4)

- Bardhan-Reflections On Indian Political EconomyDocument4 pagesBardhan-Reflections On Indian Political EconomyBhowmik ManasNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Discontent (India's Growing Crisis of Governability) - Political Change in A Democratic Developing Country (1991)Document22 pagesDemocracy and Discontent (India's Growing Crisis of Governability) - Political Change in A Democratic Developing Country (1991)Deshdeep DhankharNo ratings yet

- AnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsDocument6 pagesAnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsSandeep SoniNo ratings yet

- The Role of Ideology in India's Economic LiberalizationDocument10 pagesThe Role of Ideology in India's Economic Liberalizationnimish-adhia-6248No ratings yet

- Book Review: Journal of Development Economics Vol. 67 (2002) 485 - 490Document6 pagesBook Review: Journal of Development Economics Vol. 67 (2002) 485 - 490J0hnny23No ratings yet

- Review Article: Economic Strategies For Growth With EquityDocument7 pagesReview Article: Economic Strategies For Growth With EquityAndi Alimuddin RaufNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Regional IntegrationDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Regional Integrationc5m07hh9100% (1)

- An Economist in The Real World: The Art of Policymaking in IndiaDocument5 pagesAn Economist in The Real World: The Art of Policymaking in IndiaAashna DuggalNo ratings yet

- School Uniforms Essay IdeasDocument6 pagesSchool Uniforms Essay Ideasd3hfdvxmNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument96 pagesEconomicsRichika shekherNo ratings yet

- 14525491607.1AnuradhaBose BookReviewDocument4 pages14525491607.1AnuradhaBose BookReviewRavi JoshiNo ratings yet

- Book - Alert - August 2019Document11 pagesBook - Alert - August 2019Mayank SainiNo ratings yet

- Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in IndiaFrom EverandLocked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in IndiaNo ratings yet

- Through The Lens of Indian Youth: An Overview.: Background To The StudyDocument16 pagesThrough The Lens of Indian Youth: An Overview.: Background To The StudyNitin MalikNo ratings yet

- Developmental State Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesDevelopmental State Literature Reviewafmzynegjunqfk100% (1)

- Literature Review Economic GrowthDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Economic Growthfvgy6fn3100% (1)

- Book Alert Dec.2019Document10 pagesBook Alert Dec.2019rajd42648No ratings yet

- FiveReviewsofG - Omkarnath2012Economics APrimerforIndiaDocument17 pagesFiveReviewsofG - Omkarnath2012Economics APrimerforIndiasnehilkushwaha681No ratings yet

- Research Paper of Economics in IndiaDocument4 pagesResearch Paper of Economics in Indiaqghzqsplg100% (1)

- PP Women and Development - Haddad 0 0Document6 pagesPP Women and Development - Haddad 0 0Carmen AvilaNo ratings yet

- Political Economy PHD ThesisDocument5 pagesPolitical Economy PHD Thesislauraarrigovirginiabeach100% (1)

- FiveReviewsofG - Omkarnath2012Economics APrimerforIndiaDocument17 pagesFiveReviewsofG - Omkarnath2012Economics APrimerforIndiaSharib KhanNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Academic Research To National DevelopmentDocument11 pagesThe Significance of Academic Research To National DevelopmentIgwe DanielNo ratings yet

- January 12Document72 pagesJanuary 12Shay WaxenNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Masters Thesis Political ScienceDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Masters Thesis Political Sciencebsend5zk100% (2)

- China and India and BrazilDocument11 pagesChina and India and Brazilcsc_abcNo ratings yet

- Working Paper: Manisha Sinha and Des GasperDocument26 pagesWorking Paper: Manisha Sinha and Des GasperDeepali GuptaNo ratings yet

- Qur'anic Social Transformation in Tafsir Al AzharDocument12 pagesQur'anic Social Transformation in Tafsir Al Azharfatkhul mubinNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument13 pagesResearch ProposalMohaiminul IslamNo ratings yet

- Conceptualising Human Needs and Wellbeing: Des GasperDocument29 pagesConceptualising Human Needs and Wellbeing: Des GasperDalal ZouhdiNo ratings yet

- Ideas+and+Institutions Economic+GrowthDocument68 pagesIdeas+and+Institutions Economic+GrowthSubi SabuNo ratings yet

- Bold Strategies For Indian ScienceDocument2 pagesBold Strategies For Indian ScienceKanuri VardhanNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis in International Political EconomyDocument10 pagesPHD Thesis in International Political Economylucienicolasstockton100% (2)

- Good Governance, Democratic Societies and Globalisation by SurendraDocument5 pagesGood Governance, Democratic Societies and Globalisation by SurendraMohd AsifNo ratings yet

- GE SyllabusDocument12 pagesGE SyllabusNIMISHA DHAWANNo ratings yet

- From Economic Growth To Economic Development: The Journey With Mahbubul HaqDocument33 pagesFrom Economic Growth To Economic Development: The Journey With Mahbubul HaqAsad ZamanNo ratings yet

- PHD Dissertation Political Science PDFDocument4 pagesPHD Dissertation Political Science PDFHelpWithFilingDivorcePapersCambridge100% (1)

- Foreign Policy Ideas and State Building - Priya ChakoDocument47 pagesForeign Policy Ideas and State Building - Priya Chakoabhishekthakur19No ratings yet

- POL 243-Political Economy of Development-Dr. Noaman AliDocument4 pagesPOL 243-Political Economy of Development-Dr. Noaman AliMarjan HussainNo ratings yet

- Revised Book Review Submitted By: Nidhi RawatDocument7 pagesRevised Book Review Submitted By: Nidhi RawatNidhi GusainNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Poverty in IndiaDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Poverty in Indiaygivrcxgf100% (1)

- Possible Thesis Topics For International RelationsDocument5 pagesPossible Thesis Topics For International Relationsheidikingeugene100% (2)

- Esther Duflo: Policies, Politics:Canevidenceplaya Roleinthefightagainstpoverty?Document20 pagesEsther Duflo: Policies, Politics:Canevidenceplaya Roleinthefightagainstpoverty?ceimnet100% (1)

- Development: Of: KoreaDocument30 pagesDevelopment: Of: Koreazxy20010101jessicaNo ratings yet

- IED Sequence 4 Paper SummaryDocument7 pagesIED Sequence 4 Paper SummarySiddarth BaldwaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Meaning in ChineseDocument5 pagesDissertation Meaning in ChineseWriteMyPaperCoAtlanta100% (2)

- Ethics, Economics and Social Institutions: Vishwanath PanditDocument15 pagesEthics, Economics and Social Institutions: Vishwanath PanditshanmukhaNo ratings yet

- Public Administration and Development Administration: The NexusDocument12 pagesPublic Administration and Development Administration: The NexusMustiara SariNo ratings yet

- Comparing China and India: An Introduction: The European Journal of Comparative Economics June 2009Document4 pagesComparing China and India: An Introduction: The European Journal of Comparative Economics June 2009Upasana GuptaNo ratings yet

- Globalisation Pushing India's Rural EconomyDocument5 pagesGlobalisation Pushing India's Rural EconomyJiten BendleNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin SystemDocument4 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Wisconsin Systemrifa fauziyatul azizahNo ratings yet

- Synop, Eco 3, PDF FinalDocument7 pagesSynop, Eco 3, PDF FinalVivek VibhushanNo ratings yet

- AA DebateDocument14 pagesAA DebateBarshaNo ratings yet

- Anubhav Shukal, Book ReviewDocument7 pagesAnubhav Shukal, Book ReviewAnubhav ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Be In: India Development and Parti IpationDocument20 pagesBe In: India Development and Parti IpationAnonymous 13ulUnpZNo ratings yet

- (Varshney) Democracy, Development, and The Countryside PDFDocument229 pages(Varshney) Democracy, Development, and The Countryside PDFMario GuerreroNo ratings yet

- National Policy and Social SciencesDocument3 pagesNational Policy and Social SciencesTakreem BaigNo ratings yet

- Communitarianism EtzioniDocument5 pagesCommunitarianism EtzioniSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Rollout Prerequisites and Go Live ChecklistDocument4 pagesRollout Prerequisites and Go Live ChecklistSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- CadreAllocation 2010Document24 pagesCadreAllocation 2010Samar SinghNo ratings yet

- Medical Pro Form ADocument8 pagesMedical Pro Form ASamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Computer Awareness Questions Collection: List of Commonly Used Computer AbbreviationsDocument106 pagesComputer Awareness Questions Collection: List of Commonly Used Computer AbbreviationsSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee ActDocument2 pagesMahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee ActSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Computer TechniquesDocument1 pageComputer TechniquesSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Mao ViolenceDocument6 pagesMao ViolenceSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Citizen Charter of FCIDocument19 pagesCitizen Charter of FCISamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Frequently Asked Questions: 1. What Is The Status of Managers?Document11 pagesFrequently Asked Questions: 1. What Is The Status of Managers?Samar SinghNo ratings yet

- WR NDA I 23 NameList Engl 170523Document296 pagesWR NDA I 23 NameList Engl 170523RAVINDRASINGH CHAUHANNo ratings yet

- DeputationDocument6 pagesDeputationallumuraliNo ratings yet

- Order Branch Upgrade 2ndyr 020818Document40 pagesOrder Branch Upgrade 2ndyr 020818akash mishraNo ratings yet

- Honorary Members ListDocument4 pagesHonorary Members ListFrank HayesNo ratings yet

- Delhi'S Culture: English Project By: Group A of 9 BDocument7 pagesDelhi'S Culture: English Project By: Group A of 9 Blove for artNo ratings yet

- Joint Military Exercises of IndiaDocument6 pagesJoint Military Exercises of IndiaRavi kumarNo ratings yet

- A Study On Performance Appraisal in Event Management in DSM Textile in KarurDocument40 pagesA Study On Performance Appraisal in Event Management in DSM Textile in Karurk eswariNo ratings yet

- Central University of Karnataka - WikipediaDocument6 pagesCentral University of Karnataka - WikipediaAmitesh Tejaswi (B.A. LLB 16)No ratings yet

- IntroductionStatus of Tribal Women An Indian PerspectiveDocument5 pagesIntroductionStatus of Tribal Women An Indian PerspectiveGoswami AradhanaNo ratings yet

- 8 An Empirical Study of Selected Customers On Rural Marketing Strategies of Selected Products of Hindustan Unilever LimitDocument311 pages8 An Empirical Study of Selected Customers On Rural Marketing Strategies of Selected Products of Hindustan Unilever LimitJoanna HernandezNo ratings yet

- Tamilnadu & Puducherry Current Affairs 2018 by AffairsCloud PDFDocument27 pagesTamilnadu & Puducherry Current Affairs 2018 by AffairsCloud PDFKeerthana MNo ratings yet

- MA IV Sem Cbcs External 24122020Document6 pagesMA IV Sem Cbcs External 24122020Akash RautNo ratings yet

- Paint IndustryDocument18 pagesPaint IndustryJA SujithNo ratings yet

- Indian RailwaysDocument8 pagesIndian RailwaysMocomi KidsNo ratings yet

- East India CompanyDocument11 pagesEast India CompanyJohn PhilipsNo ratings yet

- Allama Iqbal's Address of Allahabad, 1930Document23 pagesAllama Iqbal's Address of Allahabad, 1930datid96743No ratings yet

- PROJECT REPORT by YASHDocument76 pagesPROJECT REPORT by YASHAbhishek Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- SBCI State of Play IndiaDocument46 pagesSBCI State of Play IndiaUnited Nations Environment ProgrammeNo ratings yet

- CBSE Group Mathematical Olympiad ResultDocument3 pagesCBSE Group Mathematical Olympiad ResultMota ChashmaNo ratings yet

- NeetPG2021 DataDocument117 pagesNeetPG2021 DatagarwesfvNo ratings yet

- UD Secretaries List of All States - 15apr2020Document1 pageUD Secretaries List of All States - 15apr2020vbnraoNo ratings yet

- From-Bodhgaya To Lhasa To Beijing Life & Times of Sariputra 1335-1426 Last Abbot McKeown Arthur Philip (Thesis)Document584 pagesFrom-Bodhgaya To Lhasa To Beijing Life & Times of Sariputra 1335-1426 Last Abbot McKeown Arthur Philip (Thesis)Ayush GurungNo ratings yet

- Magazine ListDocument6 pagesMagazine ListArvind SardarNo ratings yet

- MR - Basari Bhunia - 2022229 - 07-07-2023Document2 pagesMR - Basari Bhunia - 2022229 - 07-07-2023Radhagobinda BhuniaNo ratings yet

- List of Elected Reprentatives of Urban Local Bodies State-UttarakhandDocument39 pagesList of Elected Reprentatives of Urban Local Bodies State-UttarakhandShazaf KhanNo ratings yet

- Class 6-7-8-9-10-11 - 12 Political ScienceDocument109 pagesClass 6-7-8-9-10-11 - 12 Political Sciencegoyalrohit924No ratings yet

- FMCGDocument2 pagesFMCGanjaliNo ratings yet

- Joint Statement During The State Visit of The Emir of The State of Qatar To India (March 24-25, 2015)Document3 pagesJoint Statement During The State Visit of The Emir of The State of Qatar To India (March 24-25, 2015)Dinkar AsthanaNo ratings yet

- Sericulture TechniqueDocument4 pagesSericulture Techniqueshaad788No ratings yet