Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trade Finance

Uploaded by

Roger AllanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trade Finance

Uploaded by

Roger AllanCopyright:

Available Formats

6

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

Jesse Mora and William Powers

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 is widely viewed as the spark that triggered the global economic crisiswhat has become known as the Great Recession. Global credit markets froze, which may have affected the specialized financial instrumentsletters of credit and the likethat help grease the gears of international trade. Some analysts view the credit market freeze as contributing to the 31 percent drop in global trade between the second quarter of 2008 and the same quarter in 2009 (Auboin 2009). Evidence presented in this chapter suggests that declines in global trade finance had, at most, a moderate role in reducing global trade. The chapter also examines broad measures of financing, including domestic lending in major developed economies and cross-border lending among more than 40 countries. Supplementing the data are the results of eight recent surveys to provide a more thorough examination and greater confidence in the role of trade finance during the crisis. This investigation highlights several aspects of trade finance during the crisis: Trade finance is dependent on both domestic and cross-border funding. While both fell substantially in 2008, neither the timing nor the magnitude of

The authors thank Hugh Arce, Richard Baldwin, and Michael Ferrantino for their helpful comments and support. This piece represents solely the views of the authors and does not represent the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its commissioners.

117

118

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

domestic declines matched the drop in trade finance. Cross-border funding declines presented more troubling trends, however, with supply falling earlier and exceeding the drop in demand for funds. Trade finance began to recover in the second quarter of 2009 for most developed and developing countries. Latin America and Africa showed the least progress but have recently stabilized. Among all regions, Asia has had the strongest recovery. Reduced trade finance played a moderate role in the trade decline at the peak of the crisis. Banks and suppliers judged reduced trade finance as the second greatest contributor to the decline in global exports, behind falling global demand. The crisis has led to a compositional shift in trade finance. Because of heightened uncertainty and increased counterparty risk, exporters shifted away from risky open-account transactions and toward lower-risk letters of credit and export credit insurance. Financing has been a larger problem for exports than for domestic sales.

Effect of Crisis on Corporate Finance The crisis negatively affected every type of financing that companies use to fund their domestic production and international trade. Companies get financing in many ways, such as by issuing bonds or equity, obtaining bank loans, or selffinancing through retained earnings. The crisis negatively affected all of these channels: Interest rates on bonds and loans rose, while equity prices and profits felland, hence, retained earnings (Guichard, Haugh, and Turner 2009). Indexes of financial conditions based on all types of financing began falling in 2007 (or earlier) in Japan, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. U.S. financial conditions did not return to normal until the end of 2009 or the beginning of 2010 (Hatzius et al. 2010). Although strains had appeared in domestic banking markets before the trade collapse, there is no evidence that large declines in domestic lending preceded the decline in trade. (Box 6.1 describes the mechanics of how trade is exposed to financing shocks.) Strains in domestic financial markets became apparent in developed countries long before the global downturn. One early indicator of banking sector constraints was credit standards for commercial loans. In most developed countries, these standards became progressively tighter after the third quarter of 2007, as figure 6.1 illustrates. Despite the tighter standards, commercial lending actually expanded until the end of 2008, although the declines that began in 2009 generally continued into 2010, as figure 6.2 shows.

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

119

Box 6.1 Common Types of Trade Finance and the Risk for Exporters

Worldwide, firms exported about $16 trillion of goods in 2008. Firms finance most exports through open accountsthat is, the importer pays for goods after they are deliveredjust as is the usual practice for sales among firms in the same nation. This is the riskiest form of financing for an exporter, as figure B6.1 illustrates. Estimates vary, but sources report that open accounts are used for between 47 percent (Scotiabank 2007) and 80 percent (ICC 2009b, 2010) of world trade. Cash-inadvance arrangements, the least risky form of financing for exporters, account for a small share of total financing. Banks finance the remaining portion of global trade. Most bank financing involves a letter of credit, a transaction in which a bank assumes the nonpayment risk by committing to pay the exporter after goods have been shipped or delivered. This method provides greater security to the exporter and is particularly popular with small firms and in developing countries. Regardless of the type of financing, exporters can also buy export insurance to reduce risk; about 11 percent of world trade was insured in 2009. The role of bank financing is increased if one includes working capital loans, which are short-term loans to buy the inputs necessary to produce goods. Working capital loans are more important for financing export shipments than for domestic shipments because of the increased time between production and payment for exports (Amiti and Weinstein 2009).

Figure B6.1 Payment Risk

exporter open account documentary letters of collection credit least secure letters of credit documentary collection open account importer

cash-inadvance

most secure

cash-inadvance

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce 2007.

The declines averaged about 2.3 percent per quarterfar below the decline in global merchandise exports, as figure 6.3 shows. As this chapter will also show, the domestic financing drop was similar in magnitude to declines in other short-term, cross-border financing. In developing

120

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

Figure 6.1 Tightening Domestic Loan Standards

net percentage tightening standards

90 60 30 0 30 60

FY 09 3 Q

Fed

FY 06

FY 06

FY 07

FY 07

FY 08

FY 08

FY 09

BoC

ECB

BoE

BoJ

Sources: Bank of Canada 2010; Bank of England 2010; Bank of Japan 2010; ECB 2010; U.S. Federal Reserve 2010. Note: Data show credit standards reported by central banks for large firms, except for Canada, which reports an overall measure. The Bank of England does not report a single measure of credit tightening, but separate measures for fees, spreads, loan covenants, and collateral requirements all behaved similarly; fees to large firms are included here. BoC = Bank of Canada, BoE = Bank of England, BoJ = Bank of Japan, ECB = European Central Bank, Fed = U.S. Federal Reserve.

countries, lending continued to grow in 2008 and 2009, even in Asia, which had the largest decline in exports.1 Throughout the world, the lending declines that became evident later in the crisis were generally accompanied by a similarly large drop in demand for funds. For example, U.S. demand for commercial and industrial loans plunged at the beginning of 2009 (ECB 2009; U.S. Federal Reserve 2010). In emerging markets, particularly Asia, where trade decline was the largest, loan growth continued to grow throughout 2009. Thus reduced domestic financing seems an unlikely cause for the trade finance decline in most markets. It is, of course, possible that trade financing from domestic banks fell even as overall lending rose. For example, several bank surveys report that the Basel II capital adequacy requirements overstate the risks of trade financing and divert funding away from exports. And Basel II has become quite widespread; 105 countries have implemented its standards, or plan to implement them, including many emerging economies in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America (BIS 2008). Countering this possible trade finance-specific decline, though, were numerous nonbank sources of domestic support targeted specifically to trade financing. Many central banks and government stimulus programs targeted domestic

FY 10

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

121

Figure 6.2 Domestic Commercial Lending

12 quarterly change, percent 8 4 0 4 8

FY 07

FY 08

FY 07

FY 08

FY 09

FY 09

FY 06

BoC

RBoA

BoE

BoJ

Fed

Sources: Bank of Canada 2010; Reserve Bank of Australia 2010; Bank of England 2010; Bank of Japan 2010; U.S. Federal Reserve 2010. Note: Bank of Japan data reflect total loans, not only commercial loans. BoC = Bank of Canada, BoE = Bank of England, BoJ = Bank of Japan, Fed = U.S. Federal Reserve, RBoA = Reserve Bank of Australia.

Figure 6.3 Global Merchandise Exports

20

quarterly change, percent

10

10

20

30

07

08

FY 09

Q Q 1 FY 10

FY 0

FY 0

FY

FY

FY

09

United States developing countries

Source: IMF 2010.

other developed countries

FY 10

122

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

financing for exports (for example, Brazil, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore), in particular after the G-20 declaration in April 2009 (Mora and Powers 2009). Cross-Border Banking Decline Preceded Other Flows Although both domestic and international banks provide financing for trade, an examination of cross-border lending in the crisis is more instructive for several reasons: Cross-border data are more complete and detailed because of centralized reporting by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), so the data present a more complete picture of changes. Cross-border data show more troubling trends; particularly, cross-border declines are earlier and larger than changes in domestic bank flows or local currency lending of bank subsidiaries (McCauley, McGuire, and von Peter 2010, among other sources). Firms relying on cross-border financing seemed more likely to experience shortfalls. Unlike the decline in domestic lending, in which demand plummeted with supply, supply factors largely drove the fall in cross-border bank lending during the crisis, at least to emerging markets (Takts 2010). The decline in the value of global cross-border banking preceded the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and thus preceded the merchandise trade decline, as shown in figure 6.4. The decline in global outflows, and the subsequent decline in domestic lending in most countries, directly reduced the availability of all types of financing. Perhaps because the United States was among the first to enter the downturn, U.S.-based financial outflows recovered earlier than those of other countries and have since grown a bit faster than in other regions. The strength of U.S. outflows indicates a return to interbank dollardenominated lending and highlights the need for dollar funding even as real gross domestic product (GDP) around the world contracted (McGuire and von Peter 2009). Because much of trade is dependent on short-term lending (either directly through bank-intermediated export financing, such as letters of credit, or indirectly through working-capital financing), the decline in short-term banking activity, illustrated in figure 6.5, is also an important indicator. Although shortterm flows are generally quite volatile, the contraction of short-term funding has been shallower and more protracted than the decline in merchandise trade. The figure also shows that inflows into the United States, unlike outflows, continued to decline through the end of 2009.

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

123

Figure 6.4 Global Cross-Border Banking Activity amounts outstanding, in all currencies, relative to all sectors

12

external position of banks, quarterly change, percent

8 4 0 4 8

08

08

07

07

09

FY

FY

FY

FY

FY

Q 3

Q 3

Q 1

Q 1

Q 1

United States

Source: BIS 2010.

other countries

Figure 6.5 Short-Term Financing Received

15 quarterly change, percent 10 5 0 5 10 15 20

09

FY 08

FY

FY

FY

United States developing countries

Source: BIS 2010.

other developed countries

FY 09

07

07

08

FY

Q 3

FY

09

124

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

Trade Finance More Resilient than Exports In many ways, the changes in trade finance during the crisis reflected conditions in overall credit and banking markets during the period. The cost of trade finance, for example, briefly reached several hundred basis points in some markets, reflecting abnormally high financing costs throughout the financial system in the fourth quarter of 2008. Availability declined and credit standards tightened for all types of financing to firms worldwide during the period. Trade finance does have some characteristics that differ from other types of financing. Trade finance is generally priced as a share of the value of goods shipped, so it is more directly tied to the level of exports than are other financial markets, and trade finance generally reflects the seasonality exhibited by a countrys exports. Furthermore, as discussed in the survey section below, global demand for more secure types of trade finance increased during the crisis, in contrast to falling demand for other corporate financing (ECB 2009). Strong demand resulted in lower declines in trade finance than in global exports. Because all exports must be financed, at least by the exporter itself, a smaller decrease in bank financing than exports must be matched by a move away from exporter-financed open accounts. These differences also affected the timing of the decline in trade financing. Although overall financial flows declined before the trade collapse, trade-specific financing moved together with trade. Short-term export credit insurance exposure is a measure of the amount of trade financing provided by private and public insurers.2 Such insurance fell by 22 percent between the second quarter of 2008 and the same quarter of 2009. Trade financing debt incurred by countries is an imperfect proxy for the amount of financing that countries receive.3 Such debt fell by 13 percent. Figures 6.6 and 6.7 show the quarterly changes for these measures of trade finance. Data from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) provide a count of trade messages sent through the SWIFT network (ICC 2010; SWIFT 2009, 2010). These transactions accounted for about $1.5 trillion in letters of credit, or about 12 percent of global trade value.4 During the crisis, global traffic fell by more than 20 percent in 2008 and rose by about 10 percent in 2009.5 As trade finance improved in 2009, letters of credit increased while less-secure methods such as documentary collections remained flat. This finding agrees with the survey results discussed below (such as ICC 2010), which report that exporters continue to move toward more secure forms of trade financing. Comparing different regions, most of the improvement during 2009 occurred in the Asia and Pacific region, with other regions showing no change or only a slight rise in volume. In the first half of 2010 (January to May), volumes in all regions improved, though the Asia and Pacific region again showed the greatest growth (22 percent).6

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

125

Figure 6.6 Export Credit Insurance Exposure

15 10 quarterly change, percent 5 0 5 10 15 20

08

09

07

07

08

FY

09

FY

FY

FY

Q 1

Q 3

Q 1

Q 3

FY

Q 3

United States developing countries

Source: JEDH 2010.

other developed countries

Both the value and volume data show that changes in trade finance have been more moderate than changes in trade, during both the downturn and the recovery, especially as follows: By nearly all measures, trade finance declined less than trade from mid-2008 to mid-2009. Figure 6.8 shows that this was true for individual regions as well, except in Latin America. As trade recovered in 2009 and early 2010, however, export credit insurance and trade finance debt remained largely flat, with only letters of credit showing any substantial increase during 2009. The Asia and Pacific region exhibited the largest growth in both transactions and value; Latin America has grown in value, making up for its losses in the downturn, while both volume and trade decreased in developed European countries. Survey Results Because much of trade finance is not distinguishable in official statisticsfor example, our data account for only about 23 percent of total global tradedata

Q 1

Q 1

FY

FY

10

126

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

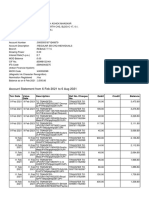

Figure 6.7 Trade Financing Debt, by Country

40 30 quarterly change, percent 20 10 0 10 20 30

08

09

07

08

FY

FY

FY

Q 1

Q 1

United States developing countries

Source: JEDH 2010.

Q 3

Q 1

other developed countries

Figure 6.8 Relative Declines in Exports, Export Insurance Exposure, and Trade Finance Debt, by Region, Q2 FY08 to Q2 FY09

Africa Asia and Pacific Europe Latin America North America

0 10

change, percent

20 30 40 50 exports trade financing debt export insurance exposure

Source: IMF 2010; JEDH 2010.

Q 3

Q 3

FY

FY

FY

09

07

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

127

comparisons are intrinsically imperfect and incomplete.7 To address the informational gap, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization, and International Chamber of Commerce have conducted surveys of global participants in the trade credit world. Overall, the surveys confirm the trends discussed above about the timing and geographic differences in trade finance. They also provide otherwise unavailable information about the effects of financing on exports; distinguish the effects of reduced bank finance supply from increased exporter demand; and highlight the importance of multilateral support during the crisis. Trade Finance the No. 2 Reason for Trade Decline at Crisis Peak Surveys show that declines in trade finance contributed directly to the decline in global trade in the second half of 2008 and early 2009. At the peak of the crisis, banks and suppliers report, reduced trade finance was the second-greatest cause of the global trade slowdown, behind falling international demand. Estimates of the relative contribution of trade finance fell in later surveys as other factors rose in prominence. In July 2009, only 40 percent of banks reported that lower credit availability contributed to declining trade, and this share decreased to less than one-third by April 2010. By the beginning of 2010, the banks reported that price declines were a larger drag on export values than trade finance limits. Financing has been less of a concern for domestic shipments, at least in the United States. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) monthly surveys of small businesses, whose sales are largely domestic, show that less than 5 percent of U.S. small businesses report that financing is their single most important problem (NFIB 2010). This share did not exceed 6 percent at any time during the crisis.8 The share of NFIB members citing poor sales as the top problem doubled during the crisis and has held at about 30 percent since late 2008. A substantially higher share of exporters cited financing as a top problem in the survey results we examine below. Collectively, these results support the argument that financing is more important for exports than for domestic shipments (Amiti and Weinstein 2009), though all surveys agree that poor demand was more important than reduced financing in limiting sales. Surveys Help Distinguish Changes in Supply and Demand Surveys provide the best evidence distinguishing changes in trade finance supply from changes in demand.9 After September 2008, the risks of exporting and

128

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

financing rose substantially because of downgraded credit ratings of firms, banks, and countries. Macroeconomic difficulties also mattereddeclining GDPs, fluctuating exchange rates, and falling prices. The rising uncertainty increased demand for more secure types of financing, such as insurance and letters of credit, to reduce the risk of nonpayment. Demand for export credit insurance rose, with the share of insured shipments rising to 11 percent of global exports in 2009 from 9 percent in 2008 (ICC 2010).10 Exporters also demanded more trade financing from banks, and half of banks reported increased demand for products such as letters of credit. As exporters tried to obtain less-risky financing, however, banks began to restrict financing to some customers to limit their own lending risk. Most surveyed banks (between 47 percent and 71 percent, depending on the survey) reduced the supply of trade financing in the last quarter of 2008. For example, the value of letters of credit fell by 11 percent in that quarter. Supply bottomed out in the first half of 2009. The value of all trade finance then rose gradually in the second half of 2009, making up for losses earlier in the year but still well below precrisis levels. Prices of letters of credit rose early in the crisis, reflecting both increased risk and the banks substantially higher cost of raising funds. As the crisis continued, increased demand and reduced supply drove trade finance prices even higher. In 2009, surveys report, prices for exporters continued to rise, even as banks were able to obtain funding more cheaply. The latest surveys report that demand remained high and was expected to increase further in 2010, while prices were not expected to fall in the short term. Conclusions This survey has included the most comprehensive measures of trade financing available, accounting for over one-fifth of global trade, and has supplemented the data with a number of trade finance surveys. This combination provides the best look to date at the changes in trade finance during the 200809 financial crisis. The evidence does not support the view that declines in trade finance were exceptional during the crisis. Overall, the declines have not been large relative to changes in trade or other financial benchmarks. For example, measures of trade finance fell by about 20 percent from peak to trough, while global exports fell by over 30 percent. Relative to other types of financing, the decline in trade finance is about the same as the decline in overall cross-border, short-term lending. Nor did trade finance have an outsize impact on trade during the crisis. Surveys show that trade finance played a moderate role at the peak of the crisis and that this role declined over time. Although prices remain high, companies no

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

129

longer report that financing costs are a major impediment to trade. Financing remains a larger problem for exporters than for domestic shippers, however, for two reasons: trade financing contracted substantially more than domestic financing, and exports require more financial support than domestic shipments. Data and surveys agree that trade finance did rebound considerably in 2009, but 2010 data have been mostly flat and conflict with the rosier gains and predictions that surveys reported. The value of all trade finance rose in the second half of 2009, making up for losses earlier in the year, but it remains well below precrisis levels. Those regions that were lagging in earlier surveys (Latin America and Africa) have seen trade finance stabilize or have begun to make up ground. The latest surveys report that exporter demand remained high and was expected to increase further in 2010. The data also show, however, that only the safest forms of trade finance rose in 2010, with total value flat or even declining. Overall, given the easing of access to credit, the trade finance situation is expected to improve. Still, as with improvement in macroeconomic conditions, the turnaround in bank attitudes and financing of all types will likely be gradual and, to a large degree, further gains in trade finance will be tied to increases in global exports.

Notes

1. For loan growth in emerging Asia, see Monetary Authority of Singapore (2009). 2. France, Germany, Italy, and the United States are the top providers of this insurance, accounting for about 25 percent of the global total. Globally, firms and agencies had close to $900 billion of such exposure before the crisis. About 90 percent of the credit guarantees are provided by private companies (Berne Union 2009). 3. The figure includes only short-term nongovernmental trade financing debt, which had a global value of $572 billion before the crisis. Debt depends on trade financing received as well as repaid, so debt may underrepresent the decline in trade financing in countries that experienced fiscal difficulties during the downturn. 4. Value data were provided for the four quarters from the fourth quarter of 2008 to the third of 2009. 5. That is, the number of transactions was about 10 percent higher in December 2009 than in December 2008, although the yearly total in 2009 was lower than the total in 2008. 6. The value of trade financing also rose in most regions during 2009, with the exception of Europe and the Middle East. Because only four quarters of value data have been reported, we cannot calculate the change for the same quarter in two consecutive years. 7. It would be possible to increase this share slightly with the currently available data. Including medium-term trade financing data from the Berne Union and documentary collection data from SWIFT would increase the covered share of global trade by about 6 percentage points. BIS also reports guarantees extended by financial institutions, including letters of credit and credit insurance in addition to contingent liabilities of credit derivatives (for example, credit default swaps). This series would be a promising source of information on trade financing if a means were devised to remove the portion related to credit default swaps, which dominate the series for some developed countries such as the United States (BIS 2009).

130

Trade Finance during the Great Trade Collapse

8. Financing has not been a top concern of small U.S. businesses in any recession since the 1980s. 9. The surveys include ICC 2009a, 2009b, 2010; IMF-BAFT 2009a, 2009b; IMF and BAFT-IFSA 2010; and Malouche 2009. 10. The share reported in ICC (2010) includes medium-term financing. The share of exports covered by short-term financing, which this report focuses on, also rose, but by less than 1 percent.

References

Amiti, Mary, and David E. Weinstein. 2009. Exports and Financial Shocks. CEPR Discussion Paper 7590, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London. Auboin, Marc. 2009. The Challenges of Trade Financing. Commentary, VoxEU.org, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London. http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/2905. BIS (Bank for International Settlements). 2008. 2008 FSI Survey on the Implementation of the New Capital Adequacy Framework in non-Basel Committee Member Countries. Financial Stability Institute, Basel, Switzerland. http://www.bis.org/fsi/fsiop2008.pdf. . 2009. Credit Risk Transfer Statistics. Committee on the Global Financial System Paper 35, Basel, Switzerland. . 2010. BIS Quarterly Review. June 2010 statistical annex, BIS, Basel, Switzerland. http://www .bis.org/statistics/bankstats.htm. Bank of Canada. 2010. Senior Loan Officer Survey on Business-Lending Practices in Canada. Bank of Canada, Ottawa. http://www.bankofcanada.ca/en/slos/index.html. Bank of England. 2010. Credit Conditions Survey: Survey Results. Bank of England, London. http:// www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/other/monetary/creditconditions.htm. Bank of Japan. 2010. Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices at Large Japanese Firms. Bank of Japan, Tokyo. http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/dl/loan/loos/index.htm. Berne Union. 2009. Yearbook. London: Exporta Publishing & Events Ltd. ECB (European Central Bank). 2009. Monthly Bulletin. November issue, Executive Board of the ECB, Frankfurt. . 2010. The Euro Area Bank Lending Survey: January 2010. ECB, Frankfurt. http://www.ecb .int/stats/pdf/blssurvey_201001.pdf?09898ebfbb522a57fa3477bc3e5022e0. Guichard, Stephanie, David Haugh, and David Turner. 2009. Quantifying the Effect of Financial Conditions in the Euro Area, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States. Economics Department Working Paper 677, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris. Hatzius, Jan, Peter Hooper, Frederic Mishkin, Kermit Schoenholtz, and Mark Watson. 2010. Financial Conditions Indexes: A Fresh Look after the Financial Crisis. Paper presented at the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum, New York, February 25. ICC (International Chamber of Commerce). 2009a. ICC Trade Finance Survey: An Interim Report Summer 2009. Banking Commission Report, ICC, Paris. . 2009b. Rethinking Trade Finance 2009: An ICC Global Survey. Banking Commission Market Intelligence Report, ICC, Paris. . 2010. Rethinking Trade Finance 2010. Banking Commission Market Intelligence Report, ICC, Paris. IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2010. International Financial Statistics Online (database). IMF, Washington, DC. http://www.imfstatistics.org/imf. IMF-BAFT (International Monetary FundBankers Association for Finance and Trade). 2009a. Global Finance Markets: The Road to Recovery. Report by FImetrix for IMF and BAFT, Washington, DC. . 2009b. IMF-BAFT Trade Finance Survey: A Survey among Banks Assessing the Current Trade Finance Environment. Report by FImetrix for IMF and BAFT, Washington, DC. IMF and BAFT-IFSA (International Monetary Fund and Bankers Association for Finance and TradeInternational Financial Services Association). 2010. Trade Finance Services: Current Environment & Recommendations: Wave 3. Report of Survey by FImetrix for IMF-BAFT, Washington, DC.

Global Perspectives in the Decline of Trade Finance

131

JEDH (Joint External Debt Hub). 2010. Joint BIS-IMF-OECD-WB Statistics (database). JEDH, http:// www.jedh.org. Malouche, Mariem. 2009. Trade and Trade Finance Developments in 14 Developing Countries PostSeptember 2008. Policy Research Working Paper 5138, World Bank, Washington, DC. McCauley, Robert, Patrick McGuire, and Goetz von Peter. 2010. The Architecture of Global Banking: From International to Multinational? BIS Quarterly Review (March): 2537. McGuire, Patrick, and Goetz von Peter. 2009. The U.S. Dollar Shortage in Global Banking. BIS Quarterly Review (March): 4763. Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2009. Financial Stability Review. Macroeconomic Surveillance Department report, Monetary Authority of Singapore. http://www.mas.gov.sg/publications/ MAS_FSR.html. Mora, Jesse, and William Powers. 2009. Did Trade Credit Problems Deepen the Great Trade Collapse? In The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects, ed. Richard Baldwin, 11526. VoxEU.org E-book, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London. http://www.voxeu.org/index .php?q=node/4297. NFIB (National Federation of Independent Business). 2010. Small Business Economic Trends. Survey report, NFIB, Nashville, TN. http://www.nfib.com/research-foundation/surveys/small-businesseconomic-trends. Reserve Bank of Australia. 2010. BanksAssets: Commercial Loans and Advances. Statistical tables, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney. http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/index.html. Scotiabank. 2007. 2007 AFP Trade Finance Survey: Report of Survey Results. Report for the Association for Financial Professionals, Bethesda, MD. SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Communication). 2009. Collective Trade Snapshot Report. Trade Services Advisory Group, SWIFT, La Hulpe, Belgium. . 2010. Data Analysis: SWIFT Traffic and Economic Recovery. Dialogue Q3 2010: 4750. Takts, Eld. 2010. Was It Credit Supply? Cross-Border Bank Lending to Emerging Market Economies during the Financial Crisis. BIS Quarterly Review (June): 4956. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2007. Trade Finance Guide: A Quick Reference for U.S. Exporters. International Trade Administration guide, U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington, DC. http://trade.gov/media/publications/pdf/trade_finance_guide2007.pdf. U.S. Federal Reserve. 2010. Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. Survey report, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC. http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/ SnLoanSurvey/201002/.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Life Mapping Workbook 2013Document14 pagesLife Mapping Workbook 2013Regent Brown93% (15)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sec Trans Outline MEE/UBEDocument8 pagesSec Trans Outline MEE/UBEArthur Shalagin100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Affordable Housing Recommendations To The Mayor ReportDocument30 pagesAffordable Housing Recommendations To The Mayor ReportMinnesota Public RadioNo ratings yet

- 300 Million Engines of Growth: A Middle-Out Plan For Jobs, Business, and A Growing EconomyDocument252 pages300 Million Engines of Growth: A Middle-Out Plan For Jobs, Business, and A Growing EconomyCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Xex10 - Working Capital Management With SolutionDocument10 pagesXex10 - Working Capital Management With SolutionJoseph Salido100% (1)

- A Simple FTP Model For A Commercial BankDocument80 pagesA Simple FTP Model For A Commercial BankMaratAyaibergenovNo ratings yet

- Uber Elevate White PaperDocument98 pagesUber Elevate White PaperRoger AllanNo ratings yet

- Commercial CasesDocument28 pagesCommercial CasesJepoy Nisperos ReyesNo ratings yet

- NCBP (NGO) ProfileDocument34 pagesNCBP (NGO) ProfileNCBP100% (1)

- Lagos State Investor Handbook FinalsDocument35 pagesLagos State Investor Handbook Finalsdavid patrick50% (2)

- Jaminan Kewangan BiDocument4 pagesJaminan Kewangan BiWilson Lim100% (1)

- Disability Services Directory June 2014Document7 pagesDisability Services Directory June 2014Roger AllanNo ratings yet

- Trilogy Monthly Income Trust PDS 22 July 2015 WEBDocument56 pagesTrilogy Monthly Income Trust PDS 22 July 2015 WEBRoger AllanNo ratings yet

- WHO - Urban Health - Major Opportunities For Improving Global Health Outcomes, Despite Persistent Health InequitiesDocument4 pagesWHO - Urban Health - Major Opportunities For Improving Global Health Outcomes, Despite Persistent Health InequitiesRoger AllanNo ratings yet

- CL-King Conference Investor-Deck Final 9-9-16Document35 pagesCL-King Conference Investor-Deck Final 9-9-16Roger AllanNo ratings yet

- Jump-Starting Malaysia's Growth - An Interview With Idris JalaDocument7 pagesJump-Starting Malaysia's Growth - An Interview With Idris JalaRoger AllanNo ratings yet

- Hedge Funds Oversight Final ReportDocument26 pagesHedge Funds Oversight Final ReportfafoouNo ratings yet

- Create Your Own Currency!Document7 pagesCreate Your Own Currency!Thomas HoyNo ratings yet

- GratuityDocument6 pagesGratuityLibraryNo ratings yet

- SBI Overview: History, Leadership, OperationsDocument59 pagesSBI Overview: History, Leadership, Operationspuneetbansal14No ratings yet

- G Mango Accounting Pack System v7 2Document13 pagesG Mango Accounting Pack System v7 2GeneVive MendozaNo ratings yet

- Williams v. United States Fidelity & Guaranty Co., 236 U.S. 549 (1915)Document5 pagesWilliams v. United States Fidelity & Guaranty Co., 236 U.S. 549 (1915)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Audit procedures for purchase transaction assertionsDocument7 pagesAudit procedures for purchase transaction assertionsnajaneNo ratings yet

- FInalDocument7 pagesFInalRyan Martinez0% (1)

- Indian BankDocument9 pagesIndian BankPraneelaNo ratings yet

- Bank Management Koch 8th Edition Test BankDocument10 pagesBank Management Koch 8th Edition Test Bankmeghantaylorxzfyijkotm100% (45)

- Public Notice REOI CMCDocument2 pagesPublic Notice REOI CMCCliantha AimeeNo ratings yet

- Sales Full Cases (Part I)Document173 pagesSales Full Cases (Part I)Niki Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- CH4+CH5 .FinincingDocument9 pagesCH4+CH5 .Finincingdareen alhadeed100% (1)

- Housing FinanceDocument10 pagesHousing FinancelakshmiNo ratings yet

- Amaefule 12 PH DDocument343 pagesAmaefule 12 PH DIrene A'sNo ratings yet

- Ohnb18 14052 CreditorsDocument2 pagesOhnb18 14052 CreditorsAnonymous YU6gbBcvu3No ratings yet

- Application-Automatic Encashment Plan FacilityDocument9 pagesApplication-Automatic Encashment Plan FacilityVishal KackarNo ratings yet

- Mr. SANTOSH ASHOK MHASKAR's account statementDocument14 pagesMr. SANTOSH ASHOK MHASKAR's account statementSantosh MhaskarNo ratings yet

- Improving settlement efficiency and mitigating risks in Hong Kong payment systemsDocument16 pagesImproving settlement efficiency and mitigating risks in Hong Kong payment systemsSathiya RameshNo ratings yet

- Micro Credit in CanadaDocument16 pagesMicro Credit in CanadatextbooksneedthemNo ratings yet

- VIT University Katpadi - Thiruvalam Road Vellore-632014Document1 pageVIT University Katpadi - Thiruvalam Road Vellore-632014AravindanNo ratings yet