Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal of Educational Administration and History 40 Év

Uploaded by

Christian WoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Educational Administration and History 40 Év

Uploaded by

Christian WoCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Educational Administration and History Vol. 40, No.

1, April 2008, 521

Educational administration and history Part 1: debating the agenda

Helen M. Guntera* and Tanya Fitzgeraldb

aSchool

of Education, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; bSchool of Education, Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

(Received December 2007; final version January 2008)

CJEH_A_292927.sgm Taylor and Francis Ltd Helen.gunter@manchester.ac.uk HelenGunter 0 100000April 2008 40 Taylor 2008 OriginalofFrancis 0022-0620Educational Administration Journal&Article 10.1080/00220620801927616(online) and History (print)/1478-7431

In this first editorial paper we scope the terrain on which the JEAH is located and consider the knowledge production process that will shape the journal and, in turn, enable the journal to shape what is known and what is worth knowing. We begin by making a case for productive pluralism where we assert that the JEAH is not directly connected to a particular society or epistemic group, and so the opportunity exists for a range of work that focuses on historical understandings of educational administration to be published. We make the argument that educational administration is a field of study and practice, and that it can draw on historical perspectives and research designs to enable new insights and theoretical explanations to be developed. Keywords: educational administration; history; field; publication; knowledge production

Introduction We begin our term of office as joint editors of the Journal of Educational Administration and History with an issue that is part of the 40th anniversary celebrations. The journal was launched in December 1968 at the University of Leeds, and was relaunched by Routledge Taylor & Francis under the editorship of Professor Roy Lowe in 2003. The particular aim in 1968 was to publish work and to stimulate interest in the fields of the administration and history of education,1 and this has remained a stable feature through the four decades since Roy Lowe opened his first volume with the following statement:

Mindful of the identity of the journal which has been established by previous editors, we will take it forward as a showcase for all that is best in the administration, history, management, leadership and politics of education. We seek to be a platform for cutting-edge scholarship and research and to turn the spotlight on a range of issues which are of current significance for those involved in both the practice and management of education. In particular, we seek to offer both historical and contemporary insights into educational practice as a contribution to the drive for ongoing improvements in the educational provision.2

Our intention is to build on this, and like Lowe we are indebted to former editors: Peter Gosden, Bill Stephens, Stuart Marriot, John Dunford, Janet Coles, Paul Sharp. Like previous editors, we

*Corresponding author. Email: helen.gunter@manchester.ac.uk 1Janet Coles, Editorial: The JEAH and the Millennium, Journal of Educational Administration and History 32, no. 1 (2000): 1. 2Roy Lowe, Editorial, Journal of Educational Administration and History 35, no. 2 (2003): 1.

ISSN 0022-0620 print/ISSN 1478-7431 online 2008 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/00220620801927616 http://www.informaworld.com

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

intend to explicitly locate the journal within the current context;3 but we also intend to establish the JEAH as a site for field development. Specifically, we intend establishing a productive conceptual and empirical relationship between educational administration and history, and hence enable the journal to be a place and space where innovative, theoretically robust research and debate can take place. Educational administration and history: one field or two?4 Educational Administration and History can be read as two separate fields with their own journals, epistemic groups, and particular interests. We give recognition to a range of journals in the UK and abroad that focus primarily on educational administration, such as Educational Management Administration and Leadership, Educational Administration Quarterly, Journal of Educational Administration, as well as to journals that publish historical work, such as History of Education, Paedagogica Historica, History of Education Review. We are aware that journals that focus on either educational administration or history do take papers that recognise and publish from the other side, as it were. Our position is that educational administration is a field where researchers draw on the discipline of history to present scholarly analysis and accounts. More of this later; but suffice to say at this point that the JEAH positions itself differently, but alongside, these separate field and disciplinary journals. In this paper, we intend to outline the territory on which the JEAH is located and through this establish a rationale for a field of researchers and practitioners who undertake historical analysis of educational administration as a prime focus. There are sufficient field members to make the journal viable and vibrant, and through their work to enable historical analyses of current issues, together with strategising on future developments, to have a dedicated space for writing, debate and analysis. The debate that we would like to begin with is central to the concerns of the JEAH. Educational administration is, at a fundamental level, about how decisions are made. Hence this opens up studies to embrace matters of policy, leadership and management, and the focus of attention can be on a range of issues such as curriculum, labour, architecture, and finances. The particular contribution that history can make to this is through: (1) Description for example, the lives of people and groups who are or have been involved can be charted and accounts provided about what happened and when; (2) Understanding for example, meanings can be generated through analysis of how people and contexts can be comprehended; (3) Explanation for example, conceptual frameworks can be used to theorise and provide reasons for how and why people and contexts are as they are and how and why things might be different; (4) Futuring for example, trajectories of possible developments can be linked from past to present to future, and positions can be taken on how and why change needs to take place. However, this could appear somewhat functional and technicist, and so we would want to make the case that historical studies can do more than use a methodology to produce claims about the truth. Indeed, we could frame an argument that turns truth on its head, and following Wagner there is a case for the aim of research being about the reduction of ignorance. The aim is to

3See the papers by Gosden 4This side heading takes

and Stephens, and Lowe, in this celebration issue. inspiration from Ron Glatters important paper about field development, Education Policy and Management: One Field or Two? in Approaches to School Management, ed. Tony Bush, Ron Glatter, Jane Goodey, and Colin Riches (London: Harper Educational Series, 1979), 2637.

Journal of Educational Administration and History

identify blank spots (what we dont know) and blind spots (what we dont know we need to know), so that we do not:

assume that what people know is constituted or limited by empirical information (we) assume instead that what people know expands to fill what they feel they need to know or want to know, and that empirical information is but one of many sources of knowledge. That is, in response to challenges of work, intimacy, political life, and other domains of activity in which they are engaged, individuals construct knowledge whether or not they have information. This knowledge some of which can take the form of self-fulfilling expectations both informs and reflects individual conceptions of gender, ethnicity, social class, community, the state and schooling.5

Hence, there is a range of histories that we might want to produce, and as researchers we need to be reflexive about what we do and how we position ourselves regarding the purposes of historical study. Our interest is in the exercise of power: who does it, when, where, why, and to what effect. In relation to education we realise the moral and values-based nature of this, not least in regard to issues about purposes and how we as a diverse society want to live together. Indeed, after nearly 300 pages outlining his approach to delivering Blairite policy as head of the Prime Ministers Delivery Unit at Number 10, Michael Barber asks himself whether the processes he designed and used are themselves moral or just a technique that can be used for good and bad ends.6 This is the central issue for all matters to do with decision-making, and it is the purpose in which decisions are located that is core to our editorship. This means we are fascinated by decision-making in ways that are more than technical (what and how), notably the control of decision-making and how interests lose and gain. Who history is written for and how it is used is a core interest, and so the JEAH is interested in socially critical work that gives recognition to histories that have so far not been written; this gives presence to people and their work in ways that are often othered. We see this as located in time and space, and hence we are interested in how in particular contexts decisions are made in particular ways. We see purposes as inevitably political, and hence we are interested in issues of social justice in regard to diversity and the postcolonial legacy. Such positioning is urgent and vital because in the current drive for what works and utility, we are striving not to be caught in the situation described by Inglis: the abominable failing of social science in its positivist mode was to kill the life it studied; the corresponding sentimentality of those who exalted a so-called phenomenology of experience was to suppose that such representation permitted understanding.7 We would agree that the demand for evidence is stifling understandings and explanations of practice, and at the same time the self-reverence of a persons story of their victory in turning round a failing school does little to explain who determines whether a school is failing and for what purposes. We would go further than this, and at a time when establishing personal identity has never been so popular for individuals to know who they are and where they come from as a family history, we are sympathetic to concerns raised by Fielding that collective and shared memories are being erased.8 It seems to us that the process of modernisation is making historical analysis of educational administration not only uncool but positively dangerous, and those who try to link reform to the ongoing patterns of

5Jon Wagner, Ignorance in Educational Research, Educational Researcher 22, no. 5 (1993): 21. 6Michael Barber, Instruction to Deliver (London: Politicos, 2007). 7Fred Inglis, Method and Morality: Practical Politics and the Science of Human Affairs, in The

Moral Foundations of Educational Research: Knowledge, Inquiry and Values, ed. Pat Sikes, Jon Nixon, and Wilfred Carr (Maidenhead: Oxford University Press), 128. 8Michael Fielding, Putting Hands Around the Flame: Reclaiming the Radical Tradition in State Education, Forum 47, nos. 2 and 3 (2005): 62.

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

development are often marginalised as condoners of poor standards and performance. It seems that the past is disconnected from the current and the future, and again following Fielding we need to reclaim our radical past if we are to make a difference to how we make decisions now to create the future: our capacity to interrogate the present with any degree of wisdom or any likelihood of creating a more fulfilling future rests significantly on our knowledge and engagement with the past and with the establishment of continuities that contemporary culture denies.9 Our aim in this opening editorial paper is to define the scope and influence of the journal by examining: (1) What is the territory on which JEAH is located? (2) What is knowledge production on this territory? (3) What are the implications of knowledge production for professional practice and membership? (4) What are the implications of this for the purposes of JEAH? In exploring these questions, we will make the case that this territory is pluralistic in relation to knowledge claims and membership. We can do this because the JEAH is not linked directly to any epistemic group, society or government agency, and so it is a place where a wide range of research and people can be represented. Scoping the territory We do not intend to begin with a settled definition of historical analyses of and within educational administration. Our approach is to scope and open up possibilities for scholarly work that is validated through peer review, and is legal and respectful of conventions on human rights. We hope to keep this in dialogue as we move through our editorship, and we welcome think pieces that develop and extend ideas about the terrain and positioning. A useful starting point is to begin which how territory is understood through an experience of the publication process. One of us began a paper in the following way:

If I begin with the core purpose of enabling and developing learners and learning then how and why resources are and should be controlled generates an imperative to organise. In order to learn students need to have access to a range of resources: first, intellectual in the form of ideas, facts and values; second, developmental in the sense of how the person comes to know their identity as learner and others as learners who learn with and from you; third, professionally in the form of teachers and support staff who are knowledgeable and skilled; fourth, material in the form of place and space with buildings, ICT, books and equipment; fifth, time as arrangements for the formal engagement with learning. This means I need to engage with how learners as individuals and as groups are organised; how staffing and material resources are deployed; and how choices are defended both technically in the form of accounts and democratically in the form of purposes. Where decisions are made on these matters together with the actions that are integral to this (talking, reading, presenting, chairing, theorizing, meeting, thinking, breathing, typing, feeling) is regarded as the focus of the field.10

A referee asked the question: isnt this obvious? Well, yes and no. This is the educational administration terrain, but it is often unstated and increasingly assumed as a given. Without restating this over and over again, then there is a danger that what is of interest becomes lost in the midst of busyness. Hence we want to map the ground on which the journal is located: first,

9Ibid., 623. 10Helen Gunter,

Conceptualising Research in Educational Leadership, Educational Management, Administration and Leadership 33, no. 2 (2005): 168.

Journal of Educational Administration and History

our attention must be focused on learners, whether they are children or adults, and we need to be attentive to the experience and conceptualisations of learning, and how learners participate in decisions about learning. Second, we are interested in the adults who work with learners: who they are, what they do, their credentials and experiences, and how they are located within professional and professionalising systems and processes. Third, the organisation is a core interest in relation to the type and location of decisions interconnected with structures and cultures. Fourth, the communities represented within the organisation and the interconnection with the wider local, regional and national communities within which the organisation is located needs to be on our agenda. Fifth, the purposes of education and how this links to provision is a central issue, not least the interrelationship between the public, private and voluntary sectors, and the role of the state in the creation of the idea of citizenship and the production of citizens. We are very much aware that in the 40 years of JEAH there have been papers that have engaged with these matters. Indeed Janet Coles11 in a recent review of the journal notes that there is a remarkable similarity of topics12 with an emphasis on home nation policy changes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, national and local reformers, with most work being on secondary and higher education.13 While there are papers that reflect the colonial legacy, there is little that engages with postcolonialism; and other continents, not least Europe, are not particularly well represented. While there are papers on national and local interests, theorisations and debates about policy processes is lacking. While there are papers about religious interests in educational provision, there is little that connects private with the public, and debates over the role of the state. And finally, while there are papers about men as reformers, the gendered power relationships are absent; as Coles states, the articles on women and gender have formed little more than a trickle during the journals existence from the publication on the first such article in 1976 to the latest in 1997. This is hardly reflection of the increased importance accorded to the issue in society in general.14 These points are picked up in the next paper, which examines what papers have appeared over the last 40 years and the recent shift in emphasis of authors. The opportunity exists in the next decade to further build on this legacy and note the range of areas where researchers and writers might focus their interests and attentions. We would like to encourage papers that: (a) are biographies and case studies in ways that connect to the bigger picture of the state and rapid international changes; (b) take a particular theme, such as postcolonialism, and/or issues of diversity, such as class, gender and ethnicity; (c) examine policymaking and policymakers from local to national, global perspectives; and, (d) examine public and private interests in the provision and construction of the purposes of education. Consequently, important issues regarding the role of the state, the nature of the public domain, policymaking and practice remain vital areas of attention for the JEAH. Enduring themes can be examined within context such as professional formation and development; privatisation and nationalisation of provision; and the relationship between education, participation and democratic development. This is by no means exhaustive, but is presented as an encouragement to think widely and creatively about how research interests and projects can have interesting things to say that are valid for the journal.

online at www.informaworld.com/jeah, and in our second editorial paper in this issue we discuss the papers in more detail. 14Coles, Editorial, 3.

11Coles, Editorial. 12Ibid., 6. 13The papers are available

10

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

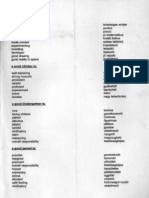

Knowledge production This brief scoping of the territory shows it to be wide open, which of itself is both exciting and problematic. It generates opportunities to rethink the focus of the field and the way in which projects are relevant to the area. However, there is more to it than this and we are aware that we need to do some more intellectual work about the nature and purposes of the terrain that we have explored so far. We would like to present in this section our view on knowledge production: what is known, how it is known, why it is known, who are the knowers, and what is regarded as worth knowing. We intend to do this by examining some enduring issues and debates, and providing our position on this. Pluralism Following work by Gunter,15 we argue that the types of knowledge and the ways of knowing practiced by researchers and published in books and journals is pluralistic. Extensive reading of field outputs over a period of nearly 20 years has led to a conceptualisation of knowledge production illustrated by Figure 1.16 This is a loose typology that has proved useful to think with in regard to knowledge claims in educational research, particularly by illuminating particular features with the opportunity to ask questions about complexities.17 The horizontal axis enables recognition to be given to research and thinking that is about challenging the world, as distinct from providing solutions for action; the vertical axis is concerned with the relationship between thinking about and taking action. This produces four main types of knowledge that we would like to see represented in the JEAH:

Figure 1. Knowledge and knowing in education.

Understanding meanings is conceptual and philosophical, where forms of knowing are based on the descriptions of settings and the thinking through of issues. For example, we would like to see the JEAH to be a site to examine the nature and purposes of schools and schooling within the public domain. Understanding experiences is biographical and artistic, where forms of knowing are based on biographical, life story and interview work. For example, we would like to encourage papers that present biographical work of people who have been involved in all aspects of educational administration. Working for change is political and visionary, where forms of knowing are based on using empirical data and theorising to work against social injustice and/or for social justice with ideas and argument. For example, we would like to encourage papers that examine meanings and illustrations of enduring social justice issues related to class, ethnicity, and gender. Delivering change is technical and outcome orientated, where forms of knowing are based on measurement studies and distillations of good practice. For example, we would like to see papers that examine issues of educational effectiveness within historical context.

The danger of this type of approach is that it could be read as advocating forms of pragmatism that could leave the journal open to a lack of identity, where anything goes. Indeed, the types of

15See, in particular: Helen Gunter and Peter Ribbins, The Field of Educational Leadership: Studying Maps and Mapping Studies, British Journal of Educational Studies 51, no. 3 (2003): 25481. 16Adapted from Helen Gunter, Leading Teachers (London: Continuum, 2005), 18. 17See, in particular: Helen Gunter, Knowledge Production in the Field of Educational Leadership: A Place for Intellectual Histories, Journal of Educational Administration and History 38, no. 2 (2006): 21015.

Journal of Educational Administration and History

11

Activity Understanding meanings Understanding experiences

Conceptual: challenging and developing understandings Humanistic: gathering and using experiences to of ontology and improve practice. epistemology.

Challenge

Descriptive: challenging and Aesthetic: appreciating and Provision developing understandings using the arts to enhance practice. of activity and actions.

Working for change

Delivering change

Critical: revealing injustice Evaluative: measuring the and emancipating those who impact of role incumbents on outcomes. experience injustice. Instrumental: providing Axiological: clarifying the values and value conflicts to strategies and tactics for effectiveness. support what is right.

Actions

Figure 1. Knowledge and knowing in education.

pluralism that are being increasingly witnessed is what Bernstein recognises as, first, flabby where there is a form of cherry-picking, where writers borrow unreflexively from other writers; second, a form of polemical pluralism where recognition of other forms of knowledge and knowing are used negatively to support one type of knowledge and knowing; and, third, tokenism where superficial note is taken of other ways of knowing and knowledge but nothing is learned from this.18 Such forms of pluralism are extreme and wild19 in ways that fragment knowledge and knowing, and are a form of absent scholarship that is evident in the shift towards securing and measuring the delivery of national reform, particularly in England. The Theory Movement from the 1950s in North America attempted a scientific and unified approach to the territory, particularly through the work of Griffiths and Halpin.20 While

Bernstein, The New Constellation (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), 36. Bernstein, The Varieties of Pluralism, American Journal of Education 95, no. 4 (1987): 522. Theory Movement in North America focused on creating an objective and reliable theory of organisations where facts and values are separated. See Dan Griffiths, Intellectual Turmoil in Educational Administration, Educational Administration Quarterly 15 (1979), no. 3: 4365.

18R.J. 19R.J. 20The

12

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

the approach in England from the 1960s claimed to be multidisciplinary, the current trend is for an approach to decision-making that is reminiscent of the drive for one theory.21 Our argument is that there is no single totality in which everything can be encompassed,22 and so what we would advocate is what Bernstein23 identifies as an engaged fallibalistic pluralism where we are willing to listen to others without denying or suppressing the otherness of the other. Consequently, we would welcome papers from a range of knowledge claims based on a recognition and respect of location and position. We would like the JEAH to be a place for what we want to call productive pluralism, where a range of thinking and projects are represented, and where the struggle over position regarding the validity and legitimacy of knowledge claims is opened up to scrutiny. What this raises are important issues regarding the power processes within the conceptualisation and operationalisation of pluralism, and it is to these issues that we now turn. Fields and disciplines The position we take is that educational administration is a field of study and practice:24 people both do professional practice and study the exercise of power through decision-making, while history is a discipline with a set of methodological procedures and claims about evidence. This is not just a matter of semantics, because we draw on Hirsts distinction between forms and fields of knowledge. The former is a discipline that is concerned with knowing the world, whereas a field is about action. A discipline therefore has central concepts forming a logical structure, with techniques and skills, and distinctive expressions which are testable against experience,25 whereas a field is not concerned to validate any one logically distinct form of expression. They are not concerned with developing a particular structuring of experience. They are held together simply by their subject matter, drawing on all forms of knowledge that can contribute to them.26 Consequently, medicine and engineering are fields that draw on knowledge from disciplines within the natural sciences; and education is a field based on the humanities and the social sciences. In taking this position we are, like Carr,27 not separating theory from practice, or treating disciplines as some form of elite type of knowing. We would also argue against using terms such as applied in regard to knowledge: methods and evidence are used within and through practical action, and consequently we contribute to the formation and development of that disciplinary knowledge: by making the twin assumptions that all practice is non-theoretical and all theory is non-practical, this approach always underestimates the extent to which those who engage in educational practices have to reflect upon, and hence theorise about, what, in general, they are trying to do.28 We do not wish to apply, like paint to a wall, theories, evidence and methods to a practical context, because that context is not static, neutral or controllable in the way that a wall normally is. We would want to see researchers ask scholarly questions about practical situations, and engage with disciplinary knowledge to create meaning about those situations, and to develop

is based on the emergence of school leadership. See Helen Gunter and Gillian Forrester, New Labour and School Leadership 19972007 (paper presented to the American Educational Research Association annual meeting, Chicago, April 1012, 2007). 22Bernstein, Varieties of Pluralism, 521. 23Bernstein, New Constellation, 336. 24Tony Bush, Theories of Educational Management (London: PCP, 1995). 25Paul Hirst, Knowledge and the Curriculum (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974), 44. 26Ibid., 46. 27Wilfred Carr, What is an Educational Practice?, in Educational Research: Current Issues, ed. Martyn Hammersley (London: PCP, 1993), 160176. 28Ibid., 162.

21This

Journal of Educational Administration and History

13

descriptions and explanations. We would also want to encourage critical engagement where analysis is related to wider matters of justice and democratic opportunities. What this means for JEAH is that we are interested in encouraging papers that engage in productive pluralism in ways that ask questions about practice that are historically located and framed. We are aware that establishing and developing the field has not so far been a productive place for historical work; indeed, George Baron, in outlining the knowledge claims for the newly emergent field in higher education in the 1960s, sees educational administration as being located within social history and not giving attention to contemporary issues of professional practice in a reforming system.29 His call for more practice-orientated studies30 is helpful in developing and including practitioner concerns onto the agenda, but it has contributed to a highly instrumental culture within the field, and one of us has shown how history is often used and abused to justify reform rather than to engage in scholarly research.31 We would like to make a case for the validity and necessity of historical study, and we are not alone in making this statement: it is easy to see how matters that are easily put into ringbinders for local implementation can look very different through historical scholarship. By ensuring that alternative stories are told, important evidence is not overlooked and claims are subjected to scrutiny. Histories of and for the field need to be written, and we are tempted to say that we need examples of Callahans analysis of how scientific administration was applied to US educational administration in the early part of the twentieth century to postwar English history. Such a rigorously researched and cogently argued account showed how business-industrial values and procedures spread into the thinking and acting of educators, countless educational decisions were made on economic or non-educational grounds.32 This resonates today in England, with interesting parallels with Callahans cult of efficiency, and we need to examine patterns, and see what is similar, what is different, and why. For example, the current emphasis on managerialism in western-style democracies, particularly performance management, is not new and important questions can be asked about antecedence and development. There are continuities and discontinuities in time and space that can be charted and explored. This can take researchers back into the nineteenth century, but also more contemporary histories can be written that place what is going on now in England with what is happening elsewhere in places where historical trends and configurations may be similar and/or different. An illustration of this is Butt and Gunters account of changes to the school workforce in England over the past five years, and how this is linked to longer-term trajectories and legacies about the status and conceptualisation of the teaching profession. Additionally, this can be looked at by writers and researchers from other parts of the world, in relation to how they are handling similar situations but within different contextual settings. Modernising the school workforce in post-apartheid South Africa is somewhat different from England, though debates about governance and the relationship between professionals, professionality and democratic development resonate within both countries.33 While the activity of decision-making is what the field is concerned with, the meanings attach to research and theorising through disciplinary knowledge. It is entirely possible for a

29George Baron, The Study of Educational Administration in England, in Educational Administration and the Social Sciences, ed. George Baron and William Taylor (London: The Athlone Press, 1969), 317 This edited collection does not have a chapter about history. 30George Baron, Research in Educational Administration in Britain, Educational Administration 8, no. 1 (1980): 133. 31Helen Gunter, Rethinking Education: The Consequences of Jurassic Management (London: Cassell, 1997). 32Raymond Callahan, Education and the Cult of Efficiency (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). 33Graham Butt and Helen Gunter, Modernizing Schools: People, Learning and Organizations (London: Continuum, 2007).

14

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

range of disciplines to be drawn upon either singly or in combination. Some researchers locate their project in sociology, in psychology, in economics as well as in history; and some connect, such as sociology and history.34 Our approach is to say that we do not want the JEAH to be a place for the history of education, but for historical analysis of educational administration. In doing this, we are mindful that history as a discipline has been, and continues to be, a place for debate about methodology and evidence, and we would embrace this. We are mindful that papers need to be methodologically rigorous, but we are also aware that history is never for itself; it is ways for someone.35 So we see the JEAH community (readers, writers, researchers) as users and contributors, and not just as curators of scholarship. We are sympathetic to Jenkins argument that different sociologists and historians interpret the same phenomenon differently through discourses that are always on the move, that are always being de-composed and re-composed; are always positioned and positioning, and which thus need constant self-examination as discourse by those who use them.36 In this way we are able to draw on important thinking that has gone on within the field and this journal in particular. Notably, we draw the readers attention to the Guest Editor Edition (38, no. 2) by Peter Ribbins, where the validity and necessity of historical method and processes came under the scrutiny of a range of scholars who use historical approaches in their work. Not least Jill Blackmore, who provokes the field to think differently about this scholarship:

Educational administration as a field can no longer ignore the material, social and cultural conditions under which students learn, teachers teach, and leaders lead. This requires the field to broaden its scope, to recognise localised professional knowledge but to also draw from philosophy, sociology, psychology, politics, as well as management theories to focus on educational problems.37

Positions and labels Implicit in our discussion so far are the power relations amongst researchers and writers who have and will contribute to this journal. Hence we base our advocacy of productive pluralism within the reality of knowledge production (who knows, how, why and is it worth knowing?) as a power process. Bourdieu38 uses field as a useful way of describing and understanding the processes of intellectual work: each field is characterised by the pursuit of a specific goal, tending to favour no less absolute investments by all (and only) those who possess the required dispositions.39 Consequently, there is a need to understand how a person enters the terrain, and positions the self and others through the staking of capital for recognition and distinction. The sending of a paper to a journal is a statement of entry and positioning within a field, and when a journal is directly linked to a particular group or society, then it is about controlling identity and acclaim. The disposition, or as Bourdieu identifies the revealing of a habitus,40 to write and work on the terrain, and to do this on a particular part of the terrain is essential to understand how and why what Bernstein calls wild and extreme pluralism operates. It is not just bad scholarship, but is part of the objective social relations between positions, and how field members struggle over borders: what are the claims to the truth within and outside of the borders?

34See Gerald Grace, School Leadership: Beyond Education Management (London: Falmer Press, 1995). 35Richard Jenkins, Rethinking History (London: Routledge, 1991), 17. 36Ibid., 9. 37Jill Blackmore, Social Justice and the Study and Practice of Leadership in Education: A Feminist

History, Journal of Educational Administration and History 38, no. 2 (2006): 1967. 38Pierre Bourdieu, In Other Words (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990). 39Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000), 11. 40Bourdieu, In Other Words.

Journal of Educational Administration and History

15

We are aware of the development of epistemic communities in different parts of the territory, and how they have positioned themselves in relation to knowledge claims. For example, school improvement focuses on the processes of change, and school effectiveness puts the emphasis on measuring the impact of processes on school outcomes. Historical studies are largely missing from within these fields, and while there have been debates about knowledge claims history does remain a marginal activity.41 Hence the doxa or knowledge claims is more open to debate outside than inside, and so the nature of the intellectual game in play where the illusio or a fundamental belief in the interest of the game and the value of the stakes which is inherent in that membership may not be recognised for what it is by those directly involved.42 Field history remains the interest of a few ourselves included and yet it is essential to how a field has a sense of itself and what its purposes are. This is the main reason why we wanted to launch our co-editorship not only with a statement about how we see the journal developing, but also by giving readers access to debates from within the pages of the JEAH over the past 40 years. The consequence of our approach is that we do not intend to associate with one or more epistemic groups, or with the various labels that they are adopted, promoted and discarded over the years. For example, we have not defined educational administration in any other way than as a busy, dynamic and highly political territory where we would like to encourage historical studies and analyses of how current issues have historical antecedence and future trajectories. We do not intend getting embroiled here in definitions of educational administration or other offshoots of it such as policy, management and leadership.43 Central to the last 40 years have been the attempts to define the territory, establish the border, and allow entry and exit by those who are disposed to stake their capital within that position or outside of it. One of us has already shown that labels and labelling is a key aspect of field activity, and the core focus of learners and decision-making about this remains the same over time; but the labels shift in the struggle of recognition and status.44 Educational administration was sidelined in England because of a struggle for status by the teaching profession where headteachers wanted to be known as managing directors. Policy strategising central to administration was transferred to management, and administration was downgraded to clerical delivery work. From the 1990s, management suffered the same fate as it became conceptualised as technical while leadership was used to characterise strategy as visioning. Headteachers became leaders and their work was relabelled as leading and leadership, in ways that enabled claims for parity of status and salaries with private companies as a means to secure the delivery of national reforms locally. The aim to establish leadership as distinct from management is not so much that the processes are separate or even connected, but rather that such a distinction was necessary if neoliberal reforms to the state in western-style democracies were to be successful. Leaders, leading and leadership had to be attached to organisational roles such as headteacher, deputy, head of department, in order for the school to be come a unit of production within the marketplace. Consequently, understandings of leadership as a relational and authentically distributed process were sidelined, and so the sharing and the communal aspect to power relationships was lost in the discourse. Performance management and the public delivery of

41Helen Gunter, Leaders and Leadership in Education (London: PCP, 2001). An exception is Dean Finks book, Good Schools/Real Schools (New York: Teachers College Press, 2000). There are historical studies of the field, for example, Harold Silver, Good Schools, Effective Schools: Judgements and Their Histories (London: Continuum, 1994). 42Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, 11. 43See Ribbins paper in this issue and his discussion about LAMPS. 44Helen Gunter, Labels and Labelling in the Field of Educational Leadership, Discourse 25, no. 1 (2004): 2142.

16

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

targets needs people who are answerable and accountable to be clearly identified. The only distribution that can take place is top-down, and it is about delegating to get the work done rather than working with knowledgeable and knowing people. The separation of a cadre of leaders led by a chief executive leader separates out the strategists from the implementers, and this enables performativity to work as a hierarchical process. Therefore, while we recognise the need for decisions to be implemented, and that this requires a formal division of labour together with productive informal relationships between people, we do not accept that this is necessarily what is now labelled as management. Getting things done is just that, and so, as Gronn has argued, if leadership is about influencing people, dressed up as vision and mission, charisma, and motivation, then why not just call it influence?45 A question we need to ask ourselves is: Why has the label of follower been accepted in ways that has enabled a particular form of leadership to flourish, and how might control of the relationship between practice and what it is called be open for debate and action? We would agree with a range of writers that it is the action, the purposes of that action, and the meanings attached to that action, that matter. As Hodgkinson states: Administration is leadership. Leadership is administration.46 We need to be aware of why we label things in the way we do and who controls this. In England, the field has seen a positioning around the headteacher as school leader from the 1960s onwards; this was strengthened as a form of performance leadership from the early 1990s onwards. Public policy drew on school effectiveness and improvement knowledge claims to frame and enable reforms to the structure and culture of education, and to the nature and credentials of the profession. School leadership spoke to and is consistent with the leader-centric nature of English culture, and to the aspirations of a profession to have a higher status in society. Notably the government under New Labour sought to directly control knowledge production through the standardisation of practice and training, and through research projects. The National College for School Leadership (NCSL) was established in 2000 as the means by which practitioners could have their identity formed and developed as leaders doing leadership in order to deliver national policy reforms. Other models and approaches, together with the sites of production, have been marginalised and positioned as esoteric and destructive.47 We would like to encourage papers that examine all of these issues from national and international perspectives, and how policy strategies have developed as a means of shaping field purposes and what counts as knowledge that is worth knowing about. Membership and players Our argument so far is that the terrain of educational decision-making is one that is about the exercise of power, and it operates as power game itself. It has been assumed that there are players, and some have been mentioned as types: government ministers, researchers, and names have also been used, but as yet we have not said anything specific. Consistent with field purposes and the conceptualisation of that as being open to historical analysis and critique, we would want to adopt productive pluralism as a term to best embrace field membership. Just as Richard Bates shows that the field itself must embrace difference if we are to live together in our communities, then we as knowledge producers must also embrace it in ways that strengthen scholarship.48

45Peter Gronn, Leadership: Who Needs It?, School Leadership and Management 23 (2006), no. 3: 26790. 46Christopher Hodgkinson, The Philosophy of Leadership (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983), 195. 47Helen Gunter and Steve Rayner, Modernising the School Workforce in England: Challenging

Transformation and Leadership?, Leadership 3, no. 1 (2007): 4764. 48Richard Bates, Can we Live Together? The Ethics of Leadership in the Learning Community (paper presented to the Annual Conference of the British Educational Leadership, Management and Administration Society, Milton Keynes, October 35, 2003).

Journal of Educational Administration and History

17

Historical studies of educational administration need not be done only by professional researchers, but also need to be done by researching professionals. We would therefore agree with the inclusive approach taken by George Baron:

Viewed in its widest sense, as all that makes possible the educative process, the administration of education embraces the activities of Parliament at one end of the scale and the activities of any home and children or students at the other. Indeed, for its effective functioning an educational system must and does rely on parents performing both legally prescribed and generally understood functions. It is important to make this point, as otherwise there is a danger that administration may be interpreted solely as the concern of officials of the Department of Education and Science and of officers of local education authorities. Indeed, the use of the term in England has been so limited that in popular usage it refers only to the latter category and is not applied to heads and others who are responsible for the organisation and running of schools. Nevertheless, there is general recognition of the administrative nature of the headmasters [sic] position, if still some unease at his [sic] being described as an administrator.49

Such inclusivity has enabled the field to be concerned with practice and the study of practice in ways that have led to field members moving from schools into higher education, and also forging links between higher education and practitioners through postgraduate programmes and research projects. People do educational administration through decision-making within and about educational purposes, policies, processes, and people, and they study it through intellectual work based on imagination, conceptualisation, description, explanation and prediction. The doing of educational administration can be unremarkable in the day-to-day activity of a school, local authority, university, national ministry, government agency, but is about making a difference to learners and their learning through the professional work of those employed and deployed to teach and care. At the end of a hard-working day or week, a person can on their own or with others think about what has gone well and not so well, and how things might be sustained or changed. Private reflection can mean that much study of practice is not in the public domain, and so much is beyond access for wider comment and analysis (unless recorded in diaries, letters and emails). Hence we recognise forms of knowing that come from experience, where the interplay between agency and structure can be opened up and analysed. Knowing can be based on a set of beliefs about what works combined with data generated within context. For example, there are accounts by head teachers of their wisdom that is passed on to others in the job or about to take up the job, because, as Edmonds notes in 1968, first appointments to headship need support and his book offers suggestions (no more) as a small contribution to a subject about which little literature seems to exist.50 The growth of postgraduate studies in England for educational professionals from the 1960s onwards in the area of educational administration has given those who do the job the opportunity to systematically study what they do and compare it with what others do through experiential accounts and data sets.51 Access to literatures outside of education combined with the contextual demands of policy reform has led to professionals adopting and using models of educational administration that are known as management and leadership. Consequently, those running and accessing postgraduate programmes can engage with such models in order to present ways in

49Baron, Study of Educational Administration in England, 6. 50E.L. Edmonds, The First Headship (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1968), 51It is interesting to note that practitioners are included as authors in

viii. Managing Education: The System and The Institution, ed. Meredydd Hughes, Peter Ribbins, and Hywel Thomas (Eastbourne: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985). This is in comparison with Baron and Taylor, Educational Administration and the Social Sciences, which was written by people in higher education.

18

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

which educational administration could be improved. Such researching professionals have been important for the field because it has been very practitioner-driven in terms of the research agenda and the prevalence of small-scale studies undertaken for dissertation work. We explored this in more depth in a special edition of the JEAH in 2007 where we presented papers from six current or former postgraduate students who through their studies examined what it means to be a practitioner who researches, and how they have been handling the interplay between practice and models of good practice.52 Notably, the field in higher education has tended to be drawn from the practitioner community through people relocating their practice, and more recently into government agencies and private consultancies. Such a shift has led to the growth in professional researchers in higher education with centres, chairs, journals and learned societies, and has consequently had an impact on scholarly publishing, a point to which we return in the next article of this issue of JEAH. The field has also attracted those who may not have a practitioner background but are interested in research and theorising as robust social science. The membership of the field is in need of research, not only through biographies of those who position themselves overtly as members through research projects and publications, but increasingly those who are in national ministries and international organisations (such as the IMF or World Bank) need to be examined in regard to their position and strategies. Finally, the field needs to engage with those who are marginalised as assumed beneficiaries of policy strategies, but are often positioned as objects rather than as subjective participants. Here we are talking about how students, parents, and communities are positioned in the field, and we would like to stimulate enquiries and papers that examine their role in decision-making. Journal purposes We expect that during our time as editors the issues about scope, orientation and projects about and within the historical analysis of educational administration will develop. As new knowledge and ways of seeing the world emerge and gain acceptance, we expect the JEAH to be involved in dialogue and reporting. Our agreed mission statement (see inside front cover and the editorial in this issue) with the editorial and international advisory boards emphasises the commitment to rigorous and scholarly papers based on historical analyses of educational administration. We would like our statement to be an open invitation based on a scoping of the field as productively pluralistic in terms of knowledge claims and the variety of knowers who we would like to encourage to write and submit papers. The choice of a journal for publication is one that Wellington and Torgerson53 have investigated, and they note that authors select journals as potential publishers of their work for a variety of reasons: custom and practice; hearsay regarding what counts as an appropriate journal for their work. They also go on to show that there are objective measures such as Impact Factors and Indexing. Such measures are increasingly being used; but, as Wellington and Torgerson argue, they are not the rational processes or indicators that might be assumed. We know that the debates about and requirements for publication in a high-status journal, and research by Wellington and Torgerson,54 show that UK professors identified 87 journals as being high status; and, as they note, it is the specialisation of fields that helps to produce such a

Gunter and Tanya Fitzgerald, Work in Progress: The Contribution of Researching Professionals to Field Development, Journal of Educational Administration and History 39, no. 1 (2007): 116. 53Jerry Wellington and Carole J. Torgerson, Writing for Publication: What Counts as a High Status, Eminent Journal?, Journal of Further and Higher Education 29, no. 1 (2005): 37. 54Ibid., 44.

52Helen

Journal of Educational Administration and History

19

long list. While generic education journals seem to top the list, we would place JEAH as a serious contender in the UK journals for reporting on work from the UK and internationally that is about educational administration and its sublabels: policy, leadership and management. We return to these arguments and this analysis in the next article. Editors have written about what it means to do the job and their motivations, though they tend to be accounts of the issues around setting up a new journal and how it locates itself in a busy landscape.55 Succession in journal editors is different because there is an inheritance, but it is also similar because there is a need to establish the particular direction that the new editor(s) wish to move in. Research into journal editing shows that there are very many reasons why people take on the role: the journal is a product of both an economic marketplace, where publishing houses operate as businesses, and an academic marketplace, where not only is publication a necessary part of research but increasingly, under performance management regimes, there is a need to demonstrate measurable outcomes.56 As Wellington and Nixon have shown, journal editors play a crucial role in (the) process of legitimation and control,57 and we are mindful of the responsibilities in this role. Following this research, we do see our role as partly technical, where we filter out papers that do not meet the general requirements for scholarly work, and are gatekeepers of quality. We are part of a game in play where prestige cannot be defined in absolute terms but is located in the views of those who talk about a journal in these terms. We would accept that journals are not sterile but are located in a values regime, and we have made this explicit as we can at this stage through this current editorial paper.58 In practice we will attempt to make this as open as possible, subject to protecting the esteem of our authors and referees. We are very mindful of the importance of peer review, and how we rely upon the expertise and experiences of our referees. We intend to take a strategic approach to referee reports, and if there is a disagreement we will send it out for a third review or even ask a colleague to arbitrate. We see this as a rare event, but we do take seriously our role as guardian of quality, and this is very difficult to quantify and can only be evident in the quality of journal papers that are published. Peer review can be problematic, but it is how it is handled that matters, and we need to make it work together as the alternatives are too worrying to contemplate. We would not wish there to be lists of national standards on publication with templates for how research is to be written up, and so we value the role of people who are internationally renowned experts in their fields, and we trust them to use their judgement wisely and in the interests of scholarly development. What we do want to stress is that we would like to develop the field through the journal; and so, in addition to receiving papers from scholars based on their contribution to the field, we will be commissioning special issues on topics that are of value to generating new insights and knowledge around a particular theme. We like the way Wellington and Nixon express the enthusiasm and enjoyment that the editors they interviewed expressed about the creative aspects of editing: the idea that as a journal editor one is somehow ahead of the game with the opportunity of nurturing and supporting a new generation of scholars and researchers is also a recurrent theme.59 This is a worthwhile approach, but it is problematic: as Duncan Waite has shown in

for example, Duncan Waite and his account of establishing the International Journal of Leadership in Education in Journals Impact on their Fields (paper presented to the Primer Encuentro International de Editores y Autores de Revistas de Educacion, Mexico City, 2005). 56This issue will be picked up in the next paper. 57Jerry Wellington and Jon Nixon, Shaping the Field: The Role of Academic Journal Editors in the Construction of Education as a Field of Study, British Journal of Sociology of Education 26, no. 5 (2005): 644. 58Waite, Journals Impact, 3. 59Wellington and Nixon, Shaping the Field, 650.

55See,

20

H.M. Gunter and T. Fitzgerald

his account of setting up the International Journal of Leadership in Education, he aimed to establish a journal that is decidedly progressive but found the forces of government intervention into field knowledge claims and projects to be highly problematic:

These forces cannot but influence journals, the articles they publish, their policies, their authors and readers. When I first began this journal, I felt a need to telephone our authors personally to encourage them to be more provocative. It seemed to me that authors were self-censoring, writing for what they perceived to be a very conservative field. The conservative norms of the field affected the authors, the scholars of the field, causing them to write more conservatively (a case of the fields impact on the journal by way of its authors).60

The dominance of the anglophone world in publishing means that are also mindful that we do not impose this conservatism on those who come from other settings. We not only want to challenge the boundaries within our own field and ask authors to question who they are writing for, but also to be more inclusive and reach out to writers outside of such traditions. We see this as central to our motivation as well; we intend to return to the matters in the editorial of our final issue, when we finally hand the baton on to a new editorial team. However, and central to our immediate concerns, is that Wellington and Nixon draw to our attention that our perspectives on defining the field and judging scholarly quality need to embrace a global perspective. Hence they ask how papers from other countries such as the Middle East, and China, may generate new and interesting vistas on research and writing. They note:

[T]he recognition of difference is perhaps the most significant means available to us in challenging the collusive tendencies implicit in the illusio, the parochialism of which always, and inevitably, defines the ground rules of the collective game within which we are subjectively implicated while seeking objectively to identify and analyse our subjective positionings.61

We value our editorial and international advisory boards membership and scholarship in helping us to give recognition to a range of knowledge claims. Pausing and moving on At this stage we intend to close this particular paper, and pick up important issues in the second editorial paper that follows. Notably we want to examine the history of JEAH and its contribution to the field as a preliminary to presenting some papers from the archive. Our final comment at this stage is to ask readers to use Waites three lenses62 to examine the impact of a journal over time. First, an epistemological lens where the job of a journal is to disseminate field knowledge, and the question that we ask is: how has this journal done this so far, and what opportunities are there for extending this over the next decade? Second, a political lens where the job of a journal is to interconnect with the micro, meso and macro contexts, and so the question that we ask is: how has the JEAH interrelated with the local, regional, national and global concerns, and in what ways does the journal mirror what is happening and/or shape it? Third, a psychological lens where a journal can take on the personality of the editor(s), and so the question that we ask is: how has this journal been shaped by the particular people involved in establishing its direction, and in what ways is it shaped by the field who undertake research, submit and referee papers? Like Waite, we will no doubt struggle with establishing a productive symmetry with authors and

60Waite, Journals Impact, 5. 61Wellington and Nixon, Shaping 62Waite, Journals Impact.

the Field, 652.

Journal of Educational Administration and History

21

referees, and we recognise that this is an ideal and that we will keep it in mind as we read and work with others in a pedagogic relationship. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our Editorial and International Advisory Boards, and anonymous referees, for their helpful comments on this paper.

Notes on contributors

Helen Gunter is Professor of Educational Policy, Leadership and Management in the School of Education, University of Manchester. She has produced over 70 publications, including books and papers on leadership theory and practice. She is particularly interested in the history of the field of leadership, with a focus on knowledge production. She is currently undertaking an ESRC-funded project into the rise of school leadership under New Labour. Her most recent book, co-edited with Graham Butt, University of Birmingham, is about workforce reform: Modernizing schools: people, learning and organizations (2007, Continuum). Tanya Fitzgerald is Professor of Education at Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland. She has written extensively on the history of womens education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In addition, Tanya has conducted a number of research projects at national and international levels on social justice and educational leadership, with a particular focus on Indigenous leadership. Tanya was awarded a Spencer Foundation Research Grant in 2007 and is currently writing a history of women professors.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Crowe - Grotius Impious HypothesisDocument35 pagesCrowe - Grotius Impious HypothesisChristian WoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Crowe - Grotius Impious HypothesisDocument35 pagesCrowe - Grotius Impious HypothesisChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Danish Folk High SchoolsDocument11 pagesDanish Folk High SchoolsChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Methodological Framework For Measuring Social InnovationDocument32 pagesA Methodological Framework For Measuring Social InnovationChristian WoNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Nobleman and Burgher A Contradiction inDocument42 pagesNobleman and Burgher A Contradiction inChristian WoNo ratings yet

- What Will Social Enterprise Look Like in Europe 2020?Document9 pagesWhat Will Social Enterprise Look Like in Europe 2020?Christian WoNo ratings yet

- RuralDevelopment ICA 2016Document10 pagesRuralDevelopment ICA 2016Christian WoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Spielmarkt 2015 MájusDocument6 pagesSpielmarkt 2015 MájusChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Joó András WW1Document19 pagesJoó András WW1Christian WoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- What If Your Organisation Was A 'Test Bed' For Social ExperimentsDocument12 pagesWhat If Your Organisation Was A 'Test Bed' For Social ExperimentsChristian WoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- David Örbin - Lund-Human GeographyDocument17 pagesDavid Örbin - Lund-Human GeographyChristian Wo100% (1)

- The Third International Conference On E LearningDocument5 pagesThe Third International Conference On E LearningChristian WoNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Gemini Study CircleDocument1 pageGemini Study CircleChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Dán Intézet Búcsú PartiDocument1 pageDán Intézet Búcsú PartiChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Experiential Education The Czech WayDocument46 pagesExperiential Education The Czech WayChristian WoNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Games4 10001Document2 pagesGames4 10001Christian WoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Games2 1111Document2 pagesGames2 1111Christian WoNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Angol FeladathozDocument1 pageAngol FeladathozChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Danube Stories - Grundtvig Programunk Záró KiadványDocument120 pagesDanube Stories - Grundtvig Programunk Záró KiadványChristian Wo100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Relaxa AnnaDocument197 pagesRelaxa AnnaChristian WoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Szociális Szövetkezetek AlapDocument18 pagesSzociális Szövetkezetek AlapChristian WoNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence OnlineDocument24 pagesArtificial Intelligence OnlineThapeloNo ratings yet

- Sandia Labs Threat CategorizationDocument44 pagesSandia Labs Threat CategorizationRyan Green100% (1)

- Capital BudgetingDocument77 pagesCapital BudgetingJoseph Jennings50% (2)

- Adopting Technological Methods in The Algerian Higher Education: Challenges and RecommendationsDocument10 pagesAdopting Technological Methods in The Algerian Higher Education: Challenges and RecommendationsSara M. TouatiNo ratings yet

- 2020 2021 Performance Evaluation FormsDocument16 pages2020 2021 Performance Evaluation FormsSiwako UtakNo ratings yet

- Relationship and Transactional Marketing Integration AspectsDocument9 pagesRelationship and Transactional Marketing Integration AspectsMuhammad Faried PratamaNo ratings yet

- Ge 2018Document57 pagesGe 2018Ira PutriNo ratings yet

- E079814 FullDocument8 pagesE079814 FullSean Allen TorreNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Future Evolution of Civil Society in The EU by 2030Document66 pagesThe Future Evolution of Civil Society in The EU by 2030Grace Kelly Marques OliveiraNo ratings yet

- NSW Public Sector Capability FrameworkDocument35 pagesNSW Public Sector Capability FrameworkTO ChauNo ratings yet

- Affluent HR Practices Followed and Implemented by Berger Paints Bangladesh LimitedDocument100 pagesAffluent HR Practices Followed and Implemented by Berger Paints Bangladesh LimitedSalman HaiderNo ratings yet

- Articulo S1 PDFDocument15 pagesArticulo S1 PDFjtrujillo12No ratings yet

- Ampalaya CandyDocument10 pagesAmpalaya CandyChandrika Millado100% (1)

- Problems in Co Education in PakistanDocument6 pagesProblems in Co Education in Pakistansaeedkhan228880% (5)

- Practice Terhadap Hasil Belajar Siswa Pada MataDocument13 pagesPractice Terhadap Hasil Belajar Siswa Pada Mataafief Clara rianaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundations in Nursing: Ma. Criselda C. Ultado, RN, MANDocument348 pagesTheoretical Foundations in Nursing: Ma. Criselda C. Ultado, RN, MANJanelle Gift SenarloNo ratings yet

- E Thesis Uas DharwadDocument5 pagesE Thesis Uas DharwadLori Head100% (1)

- Literature Review Waikato UniversityDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Waikato Universityfihum1hadej2100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- FS2 - Episode 14Document6 pagesFS2 - Episode 14Banjo L. De Los Santos77% (22)

- Green HRM Practices and Strategic Implem PDFDocument7 pagesGreen HRM Practices and Strategic Implem PDFRenov RainbowNo ratings yet

- Evaluasi Penerapan Metode Penghitungan Kerugian Negara Dalam Membantu Penanganan Kasus Tindak Pidana KorupsiDocument13 pagesEvaluasi Penerapan Metode Penghitungan Kerugian Negara Dalam Membantu Penanganan Kasus Tindak Pidana KorupsiDewa Ayu PutriNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PAPER FORMAT and The BACK MATTERSDocument23 pagesRESEARCH PAPER FORMAT and The BACK MATTERSKayceej PerezNo ratings yet

- Lexical Semantics Analysis - An IntroductionDocument10 pagesLexical Semantics Analysis - An Introductiontaiwoboluwatifeemmanuel2001No ratings yet

- Anam ProjectDocument55 pagesAnam Projectshiv infotechNo ratings yet

- The Behaviour of Companies Facing A Crisis - The Recent Italian EXperienceDocument105 pagesThe Behaviour of Companies Facing A Crisis - The Recent Italian EXperienceJamal AbdallaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Clinical Consensus Strategies To Repair Ruptures in The Therapeutic AllianceDocument23 pagesHHS Public Access: Clinical Consensus Strategies To Repair Ruptures in The Therapeutic AllianceMartin SeamanNo ratings yet

- HDFC Bank ReportDocument43 pagesHDFC Bank ReportAnkit SinhaNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PAPER (Chapter 1-5)Document31 pagesRESEARCH PAPER (Chapter 1-5)reniefNo ratings yet

- Complete FinalDocument44 pagesComplete FinalNorilleJaneDequina100% (1)

- Lecture 4 Research DesignDocument40 pagesLecture 4 Research DesignTuongPhan100% (1)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverFrom EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (186)

- High Road Leadership: Bringing People Together in a World That DividesFrom EverandHigh Road Leadership: Bringing People Together in a World That DividesNo ratings yet

- Summary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendFrom EverandSummary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)