Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Capitalism Can Save Art and Inspire a New Generation

Uploaded by

Dave GreenOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Capitalism Can Save Art and Inspire a New Generation

Uploaded by

Dave GreenCopyright:

Available Formats

October 5, 2012 How Capitalism Can Save Art Camille Paglia on why a new generation has chosen iPhones

and other glittering g adgets as its canvas By CAMILLE PAGLIA Does art have a future? Performance genres like opera, theater, music and dance are thriving all over the world, but the visual arts have been in slow decline f or nearly 40 years. No major figure of profound influence has emerged in paintin g or sculpture since the waning of Pop Art and the birth of Minimalism in the ea rly 1970s. Warhol grew up in industrial Pittsburgh. Today's college-bound rarely have direc t contact with the manual trades. Yet work of bold originality and stunning beauty continues to be done in archite cture, a frankly commercial field. Outstanding examples are Frank Gehry's Guggen heim Museum Bilbao in Spain, Rem Koolhaas's CCTV headquarters in Beijing and Zah a Hadid's London Aquatic Center for the 2012 Summer Olympics. What has sapped artistic creativity and innovation in the arts? Two major causes can be identified, one relating to an expansion of form and the other to a cont raction of ideology. Painting was the prestige genre in the fine arts from the Renaissance on. But pa inting was dethroned by the brash multimedia revolution of the 1960s and '70s. P ermanence faded as a goal of art-making. More from Review The Saturday Essay: Prescription for Addiction Bernanke on Baseball: A Beacon for D.C. .But there is a larger question: What do contemporary artists have to say, and t o whom are they saying it? Unfortunately, too many artists have lost touch with the general audience and have retreated to an airless echo chamber. The art worl d, like humanities faculties, suffers from a monolithic political orthodoxy an upp er-middle-class liberalism far from the fiery antiestablishment leftism of the 1 960s. (I am speaking as a libertarian Democrat who voted for Barack Obama in 200 8.) Today's blas liberal secularism also departs from the respectful exploration of w orld religions that characterized the 1960s. Artists can now win attention by im itating once-risky shock gestures of sexual exhibitionism or sacrilege. This tre nd began over two decades ago with Andres Serrano's "Piss Christ," a photograph of a plastic crucifix in a jar of the artist's urine, and was typified more rece ntly by Cosimo Cavallaro's "My Sweet Lord," a life-size nude statue of the cruci fied Christ sculpted from chocolate, intended for a street-level gallery window in Manhattan during Holy Week. However, museums and galleries would never tolera te equally satirical treatment of Judaism or Islam. It's high time for the art world to admit that the avant-garde is dead. It was k illed by my hero, Andy Warhol, who incorporated into his art all the gaudy comme rcial imagery of capitalism (like Campbell's soup cans) that most artists had st ubbornly scorned. The vulnerability of students and faculty alike to factitious theory about the a rts is in large part due to the bourgeois drift of the last half century. Our wo efully shrunken industrial base means that today's college-bound young people ra

rely have direct contact any longer with the manual trades, which share skills, methods and materials with artistic workmanship. Warhol, for example, grew up in industrial Pittsburgh and borrowed the commercia l process of silk-screening for his art-making at the Factory, as he called his New York studio. With the shift of manufacturing overseas, an overwhelming numbe r of America's old factory cities and towns have lost businesses and population and are struggling to stave off disrepair. That is certainly true of my birthpla ce, the once-bustling upstate town of Endicott, N.Y., to which my family immigra ted to work in the now-vanished shoe factories. Manual labor was both a norm and an ideal in that era, when tools, machinery and industrial supplies dominated d aily life. For the arts to revive in the U.S., young artists must be rescued from their san itized middle-class backgrounds. We need a revalorization of the trades that wou ld allow students to enter those fields without social prejudice (which often em anates from parents eager for the false cachet of an Ivy League sticker on the c ar). Among my students at art schools, for example, have been virtuoso woodworke rs who were already earning income as craft furniture-makers. Artists should lea rn to see themselves as entrepreneurs. Creativity is in fact flourishing untrammeled in the applied arts, above all ind ustrial design. Over the past 20 years, I have noticed that the most flexible, d ynamic, inquisitive minds among my students have been industrial design majors. Industrial designers are bracingly free of ideology and cant. The industrial des igner is trained to be a clear-eyed observer of the commercial world which, like i t or not, is modern reality. Capitalism has its weaknesses. But it is capitalism that ended the stranglehold of the hereditary aristocracies, raised the standard of living for most of the w orld and enabled the emancipation of women. The routine defamation of capitalism by armchair leftists in academe and the mainstream media has cut young artists and thinkers off from the authentic cultural energies of our time. Over the past century, industrial design has steadily gained on the fine arts an d has now surpassed them in cultural impact. In the age of travel and speed that began just before World War I, machines became smaller and sleeker. Streamlinin g, developed for race cars, trains, airplanes and ocean liners, was extended in the 1920s to appliances like vacuum cleaners and washing machines. The smooth wh ite towers of electric refrigerators (replacing clunky iceboxes) embodied the el egant new minimalism. "Form ever follows function," said Louis Sullivan, the visionary Chicago archite ct who was a forefather of the Bauhaus. That maxim was a rubric for the boom in stylish interior dcor, office machines and electronics following World War II: Ol ivetti typewriters, hi-fi amplifiers, portable transistor radios, space-age TVs, baby-blue Princess telephones. With the digital revolution came miniaturization . The Apple desktop computer bore no resemblance to the gigantic mainframes that once took up whole rooms. Hand-held cellphones became pocket-size. Young people today are avidly immersed in this hyper-technological environment, where their primary aesthetic experiences are derived from beautifully engineere d industrial design. Personalized hand-held devices are their letters, diaries, telephones and newspapers, as well as their round-the-clock conduits for music, videos and movies. But there is no spiritual dimension to an iPhone, as there is to great works of art. Thus we live in a strange and contradictory culture, where the most talented col lege students are ideologically indoctrinated with contempt for the economic sys tem that made their freedom, comforts and privileges possible. In the realm of a

rts and letters, religion is dismissed as reactionary and unhip. The spiritual l anguage even of major abstract artists like Piet Mondrian, Jackson Pollock and M ark Rothko is ignored or suppressed. Thus young artists have been betrayed and stunted by their elders before their c areers have even begun. Is it any wonder that our fine arts have become a wastel and? Ms. Paglia is University Professor of Humanities and Media Studies at the Univers ity of the Arts in Philadelphia. Her sixth book, "Glittering Images: A Journey T hrough Art From Egypt to Star Wars," will be published Oct. 16 by Pantheon. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444223104578034480670026450.html#p rintMode

You might also like

- From Printing to Streaming: Cultural Production under CapitalismFrom EverandFrom Printing to Streaming: Cultural Production under CapitalismNo ratings yet

- The Art World ExpandsDocument35 pagesThe Art World ExpandsAnonymous YoF1nHvRNo ratings yet

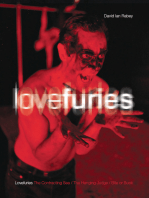

- Lovefuries: The Contracting Sea; The Hanging Judge; Bite or SuckFrom EverandLovefuries: The Contracting Sea; The Hanging Judge; Bite or SuckNo ratings yet

- Kitsch and Aesthetic EducationDocument12 pagesKitsch and Aesthetic EducationmadadudeNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- The Story of Post-Modernism: Five Decades of the Ironic, Iconic and Critical in ArchitectureFrom EverandThe Story of Post-Modernism: Five Decades of the Ironic, Iconic and Critical in ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Lawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'Document3 pagesLawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'myersal100% (1)

- Fusing Lab and Gallery: Device Art in Japan and International Nano ArtFrom EverandFusing Lab and Gallery: Device Art in Japan and International Nano ArtNo ratings yet

- Curtains?: The Future of the Arts in AmericaFrom EverandCurtains?: The Future of the Arts in AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Is Our Culture in Decline?: PolicyreportDocument4 pagesIs Our Culture in Decline?: PolicyreportpajerooooNo ratings yet

- 18th and 19th Century EuropeDocument9 pages18th and 19th Century EuropeArce RostumNo ratings yet

- Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Don't Get StockhausenFrom EverandFear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Don't Get StockhausenRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence AllowayDocument1 pageThe Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Allowaymacarena vNo ratings yet

- Ziarek - The Force of ArtDocument233 pagesZiarek - The Force of ArtVero MenaNo ratings yet

- Design As An Attitude Chapter 2 Alice RawthornDocument10 pagesDesign As An Attitude Chapter 2 Alice RawthornEmma WrightNo ratings yet

- Art in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis and Cultural StrategyFrom EverandArt in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis and Cultural StrategyNo ratings yet

- What Is Modern and Contemporary Art May 2010Document15 pagesWhat Is Modern and Contemporary Art May 2010ali aksakalNo ratings yet

- Creative Destruction: How Globalization Is Changing the World's CulturesFrom EverandCreative Destruction: How Globalization Is Changing the World's CulturesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- The Culture Industry: Enlightenment As DeceptionDocument15 pagesThe Culture Industry: Enlightenment As Deceptionmschandorf100% (1)

- The Global Work of Art: World's Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of ExperienceFrom EverandThe Global Work of Art: World's Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of ExperienceNo ratings yet

- The Art of Steampunk, Revised Second Edition: Extraordinary Devices and Ingenious Contraptions from the Leading Artists of the Steampunk MovementFrom EverandThe Art of Steampunk, Revised Second Edition: Extraordinary Devices and Ingenious Contraptions from the Leading Artists of the Steampunk MovementNo ratings yet

- The Warhol Economy (First Chapter)Document17 pagesThe Warhol Economy (First Chapter)The100% (2)

- The State and the Arts: Articulating Power and SubversionFrom EverandThe State and the Arts: Articulating Power and SubversionJudith KapfererNo ratings yet

- 34.1higgins IntermediaDocument6 pages34.1higgins IntermediaEleanor PooleNo ratings yet

- Kitsch 1Document12 pagesKitsch 1Irina Demeter100% (1)

- Resumen de La Historia Del DiseñoDocument33 pagesResumen de La Historia Del DiseñoLuis de PalauNo ratings yet

- The Knowledge Web: From Electronic Agents to Stonehenge and Back -- AFrom EverandThe Knowledge Web: From Electronic Agents to Stonehenge and Back -- ARating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the CenturyFrom EverandAmusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Behemoth. A History of The Factory de Joshua B. FreemanDocument455 pagesBehemoth. A History of The Factory de Joshua B. FreemanPerla ValeroNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition SocietyFrom EverandArts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition SocietyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and MarketsFrom EverandA History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and MarketsTitia HulstNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition SocietyFrom EverandArts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition SocietyNo ratings yet

- Journey Through The Checkout RacksDocument4 pagesJourney Through The Checkout RacksDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The New Abortion BattlegroundDocument4 pagesThe New Abortion BattlegroundDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Document3 pagesThe Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Dave GreenNo ratings yet

- Traditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDocument9 pagesTraditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDave GreenNo ratings yet

- On TransienceDocument2 pagesOn TransienceDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Portrait of The Artist As A CavemanDocument8 pagesPortrait of The Artist As A CavemanDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Me, Me, Me' WeddingDocument4 pagesThe Me, Me, Me' WeddingDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Dead Are More VisibleDocument2 pagesThe Dead Are More VisibleDave GreenNo ratings yet

- 2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDocument4 pages2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Double Helix Meets God ParticleDocument1 pageDouble Helix Meets God ParticleDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Against Environmental PanicDocument14 pagesAgainst Environmental PanicDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Why This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDocument3 pagesWhy This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Egypt's High Value On VirginityDocument3 pagesEgypt's High Value On VirginityDave Green100% (1)

- Hieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDocument34 pagesHieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Language and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDocument7 pagesLanguage and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDave GreenNo ratings yet

- France's Cul-De-SacDocument3 pagesFrance's Cul-De-SacDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Language As ActionDocument3 pagesLanguage As ActionDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Dis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Document202 pagesDis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Dave GreenNo ratings yet

- Big Data Is Not Our MasterDocument2 pagesBig Data Is Not Our MasterDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Lost BoysDocument3 pagesThe Lost BoysDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Is 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Document8 pagesIs 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Dave GreenNo ratings yet

- How A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDocument2 pagesHow A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Numbers Don't LieDocument4 pagesThe Numbers Don't LieDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDocument5 pagesThe Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Red Menace or Paper TigerDocument6 pagesRed Menace or Paper TigerDave GreenNo ratings yet

- A Dark Night IndeedDocument12 pagesA Dark Night IndeedDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Lost BoysDocument3 pagesThe Lost BoysDave GreenNo ratings yet

- To Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDocument3 pagesTo Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDave GreenNo ratings yet

- The High Cost of FreeDocument7 pagesThe High Cost of FreeDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Sympathy DeformedDocument5 pagesSympathy DeformedDave GreenNo ratings yet

- Barcoo Independent 150509Document6 pagesBarcoo Independent 150509barcooindependentNo ratings yet

- WBS Activity List Full1 1Document162 pagesWBS Activity List Full1 1muradagasiyevNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 Art Lesson 3Document24 pagesGrade 9 Art Lesson 3KC ChavezNo ratings yet

- Latvia BrochureDocument19 pagesLatvia BrochureraluchiiNo ratings yet

- N5 History of Art June 2021Document11 pagesN5 History of Art June 2021motsepe725No ratings yet

- DPWH construction project in Bugtong KawayanDocument8 pagesDPWH construction project in Bugtong KawayanMae AromazNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture - 1: Pre-Historic Civilization Module - 1.1Document34 pagesHistory of Architecture - 1: Pre-Historic Civilization Module - 1.1Noori Dhillon100% (1)

- Rajasthan Vernacular ArchitectureDocument14 pagesRajasthan Vernacular ArchitectureDiahyan KapseNo ratings yet

- How To Identify An Old BandoneonDocument32 pagesHow To Identify An Old BandoneonHeeju Oh100% (1)

- Henri MatisseDocument23 pagesHenri MatisseCristina Eileen Hodgson100% (1)

- African StonehengeDocument9 pagesAfrican StonehengeAtraNo ratings yet

- Regionalism Art and Architecture of The Regional Styles 750 AD To c.1200 (Deccan and South India)Document21 pagesRegionalism Art and Architecture of The Regional Styles 750 AD To c.1200 (Deccan and South India)AnabilMahantaNo ratings yet

- Renaissance and Baroque Arts: Learner's ModuleDocument25 pagesRenaissance and Baroque Arts: Learner's Modulespine clubNo ratings yet

- Banksy UnitDocument15 pagesBanksy Unitapi-242481603No ratings yet

- Windrush Square: Landscape Materials and TechniquesDocument55 pagesWindrush Square: Landscape Materials and Techniquesdibsdadon935No ratings yet

- Chapter - 32 Customs Tariff Code of BangladeshDocument4 pagesChapter - 32 Customs Tariff Code of BangladeshMd. Badrul IslamNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4 Brick Masonry Construction PDFDocument92 pagesLecture 4 Brick Masonry Construction PDFLee Ming100% (2)

- Heffley's Interview with Brötzmann on Machine GunDocument29 pagesHeffley's Interview with Brötzmann on Machine GunPerpetual PiNo ratings yet

- Viljoen FVB Ornamentation PHD Thesis Univ Pretoria 1985Document384 pagesViljoen FVB Ornamentation PHD Thesis Univ Pretoria 1985Robert Hill100% (1)

- American Indian & Ethnographic Art - Skinner Auction 2685BDocument156 pagesAmerican Indian & Ethnographic Art - Skinner Auction 2685BSkinnerAuctions100% (1)

- Bar Chart MetroDocument105 pagesBar Chart MetroVirendra ChavdaNo ratings yet

- Demo of The Ebook Opaque Corsets Tatiana KozorovitskyDocument59 pagesDemo of The Ebook Opaque Corsets Tatiana KozorovitskyAlejandra Ramos100% (4)

- E Commerce Jury NIFTDocument21 pagesE Commerce Jury NIFTAkanksha SharmaNo ratings yet

- End-of-Term 3 Standard Without AnswersDocument4 pagesEnd-of-Term 3 Standard Without AnswersNuria GLNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument5 pagesIndustrial RevolutionSurekha ChandranNo ratings yet

- A Working List of Crafts Currently Practised in AustraliaDocument3 pagesA Working List of Crafts Currently Practised in AustraliaLaura OrbuNo ratings yet

- Alex Gappert Portfoliotrackker2Document3 pagesAlex Gappert Portfoliotrackker2api-314087783No ratings yet

- BÀI TẬP SỐ 125-126Document9 pagesBÀI TẬP SỐ 125-126cynthiadiep100% (1)

- Philippine Arts Summative Test Analyzes Regional WorksDocument2 pagesPhilippine Arts Summative Test Analyzes Regional WorksVirgitth QuevedoNo ratings yet

- LAS in Mapeh Week 1-2Document2 pagesLAS in Mapeh Week 1-2Janrey Catuday ManceraNo ratings yet

![Locality, Regeneration & Divers[c]ities](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/294396656/149x198/794c4c2929/1709261139?v=1)