Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Termination of Psycodynamic Psychotherapy With Adolescents, Review

Uploaded by

juaromerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Termination of Psycodynamic Psychotherapy With Adolescents, Review

Uploaded by

juaromerCopyright:

Available Formats

Termination Delgado

in

and

adolescent

therapy Strawn

Termination of psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents: A review and contemporary perspective

Sergio V. Delgado, MD Jeffrey R. Strawn, MD In psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents, terminationthe phase of treatment during which the patient and his or her parents end a therapeutic relationship with a therapisthas received limited attention in the extant literature. Despite this oversight, termination is of critical clinical importance. This phase of psychotherapy with adolescents is heralded by the integration and consolidation of progress, relational changes, and the relinquishing of the symptoms that brought the adolescent to treatment. Herein, the relevant literature surrounding termination in psychodynamic psychotherapeutic work with adolescents will be reviewed. Important aspects of termination will be highlighted and discussed, including (1) criteria for termination, (2) techniques for working with parents, (3) forced terminations, (4) countertransference, and (5) common complications that arise during this phase of treatment. Finally, the complexities of the termination process as well as recent contributions to our understanding of this critically important process from attachment theory and intersubjectivity will be illustrated with clinical material. (Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 76[1], 2152)

A definition of a successful termination in adolescent psychotherapy remains as elusive as does the definition of happiness during adolescence. For decades, the treatment of adolescents who suffered from severe, functionally impairing and developDr. Delgado is Professor of Psychiatry, Child Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis at Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio. Dr. Strawn is Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, and the University of Cincinnati. Correspondence may be sent to Dr. Delgado at Cincinnati Childrens Hospital, 3333 Burnet Avenue, ML 3014, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: Sergio.Delgado@cchmc.org. (Copyright 2012 The Menninger Foundation)

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

21

Delgado and Strawn

ment-arresting psychopathology was psychoanalysis and later long-term psychoanalytically informed psychotherapy. As such, the concept of termination in adolescent psychotherapy appeared in early psychoanalytic literature and was conceptualized using Sigmund Freuds psychoanalytic work with adults. According to early psychoanalytic theory, termination required the resolution of symptoms and inhibitions with confirmation from the analyst that sufficient unconscious material had been analyzed to prevent the repetition of old neurotic patterns (Ferenczi & Rank, 1925; S. Freud, 1937/1964). However, in recent years, psychoanalytic treatments, despite their efficacy (Fonagy & Target, 1994; Target & Fonagy, 1994a, 1994b), have been used with less frequency in the treatment of youth. In fact, some have considered them to be impractical because of the decline in the availability of child and adolescent psychoanalysts, the length of treatments (usually 3 years or more), financial costs, and the limitations on session frequency and treatment duration imposed by managed care (Bleiberg, Fonagy, & Target, 1997, Plakun, 2006). Beginning in the 1960s, training in psychodynamic psychotherapy began to supplant traditional analytic training for many psychotherapists and became required for residents and fellows in child and adolescent psychiatry, as well as graduate students in psychology and social work programs. In these training programs, therapeutic work, which occurred in the context of school or program requirements, was usually limited to the students or trainees time in training (Bostic, Shadid, & Blotcky, 1996; De Bosset & Styrsky, 1986; Fox, Nelson, & Bolman, 1969). Typically, the training in adult psychiatry was a 34 year endeavor and thus allowed the trainees to have cases in psychotherapy for at least 2 years. However, in child and adolescent psychiatry training programs, trainees would, on average, have psychotherapy cases for 11 years. Therefore, the child and adolescent psychiatry fellow would have limited experience with the termination of long-term therapeutic processes during his or her training. Furthermore, over the past two decades other forms of individual psychotherapy for adolescents have been added to the psychotherapeutic armamentarium, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Southam-Geraw, Henin, Chu, Marrs, &

22

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

Kendall, 1997), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT; Moreau & Mufson, 1997), all of which are considered a short-term psychotherapy process, and thus the concept of termination has significantly evolved. However, the termination criteria in short-term psychotherapies are clearly defined by the achievement of goals and by the number of sessions. In short, the plan for termination in these psychotherapies is often determined at the beginning of treatment. By contrast, in psychodynamic psychotherapy, treatment is a mutual journey in which the ending and the duration of treatment are, in many cases, unknown at the beginning of treatment. Importantly, however, the complex process of termination in psychodynamic psychotherapy, including the countertransference aspects, has received limited attention in the extant literature (Weddington & Cavenar, 1979). Herein, the relevant writings and work surrounding termination of adolescent psychodynamic psychotherapy will be reviewed, and important aspects of this process will be highlighted, including criteria for termination, working with parents, and forced terminations. In addition, we will provide useful criteria for the termination of psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents and will describe the common complications that arise during this phase of treatment. The termination process and its complexities will be illustrated with clinical material that will highlight these aspects as well as illustrate the use of these proposed criteria for termination, all of which are influenced by the changes brought forth by attachment theory and intersubjectivity.

A working concept of termination

Certainly, the concept of termination in psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents will have to be defined in terms of contemporary psychoanalytic theories: ego psychology, attachment theory, object relations theory, and intersubjective and relational theory. That is to say, termination as a concept will also have to account for recent changes in the understanding of adolescence, not as a period of turmoil (A. Freud, 1958) but as a period during which psychological and cognitive maturation occurs (Briggs,

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

23

Delgado and Strawn

2002; Stortelder & Ploegmakers-Burg, 2010). As such, adolescence is characterized by an increasing capacity to regulate shifts in affective states, to use the abstract self, and to negotiate the complexities of the internal object world while simultaneously relating and attending to the needs of the external world (Delgado, Strawn, & Jain, 2012). Herein, we propose to define termination as the time when the adolescent and his or her parents end a therapeutic relationship with the therapist, which is marked by the adolescents resumption of a course of healthy psychological development by the integration of the work achieved during the therapy and by improvement in the symptoms that originally brought the young patient to treatment. However, we also recognize that termination is a process (Ekstein, 1965). A successful termination, in broad terms, is a dress rehearsal in which the adolescent uses newly acquired ego strengths and capacities achieved during psychotherapy to manage future, stressful life events. After all, termination centrally involves loss and separation and shifts of affect (Fox et al., 1969; Wallach, 1975) that subtend these developing ego strengths. Thus, termination is heralded by dysfunctional patterns no longer needing to be repeated, healthier relationships with new objects becoming apparent, and the relinquishing of pathological defenses (Bleiberg et al., 1997).

Review of pertinent literature

From the classic psychoanalytic perspective, termination is the completion of a process in which the patient has worked through the transference neurosis and has made intrapsychic changes that free him or her from early neurotic conflicts. Accordingly, this process allows character structure to be improved (S. Freud, 1937/1964; Sandler, Kennedy, & Tyson, 1980) and facilitates the resolution of presenting symptoms. Moreover, developmental delays from conflicts in either the preoedipal or oedipal phase have been resolved (A. Freud, 1958), and a set of stable new object relations that encourage social reciprocity is formally established (Kernberg, 1991). In addition, termination in adolescent psychotherapy has been thought to require the patients successful working through of the regressive pressures of early ties to the

24

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

parents and the capacity to intrapsychically separate and individuate within the context of his or her environment (Blos, 1967). Smirnoff (1971), in referring to analytic termination with adolescents, generally accepted the previously described elements, including symptom reduction and improved ego function, but also added that youth who were terminating treatment had to have developed a capacity for fantasy life, sublimatory activities and autonomy from fantasy (p. 330). Paulina Kernberg (1991) focused particular attention on these changes in the intrapsychic world, noting that the young patient who is nearing a successful termination has developed object constancy, including the effective integration of positive and negative object and self-images and has made significant gains in ego function (including level of defenses and affect modulation). For many, the goals for termination included symptom reduction (Kernberg, 1991; Smirnoff, 1971) and a resumption of normal development or a progression of defenses to the appropriate developmental level (Abrams, 1978; Burgner, 1988; A. Freud, 1971; Sandler et al., 1980) that allows for continued change after termination. Regarding the termination of psychotherapy with adolescents, some have viewed this process as an opportunity for a pause in the therapeutic process (Ekstein, 1983); others have conceptualized termination as a true end to treatment. Still, a minority of theorists have likened the termination process to that of successful separation (Burgner, 1988; Weis, 1991). Accordingly, students of psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents are often frustrated by these seemingly competing constructs of termination and may find themselves agreeing with Weiss (1991) observation that the field has never clearly defined for itself what is involved in termination (p. 268; see also Maholick & Turner, 1979 ). For Ferro (2006/2008), the analysts theoretical orientation is secondary to how his or her personality allows him or her to interact with the patient (p. 1317) and to be responsive to the patients level of functioning, thus, the analyst and patient mutually shape the termination process. In the nonpsychoanalytic literature, it is generally accepted that terminationa process common to most forms of psychotherapyshould occur following the completion of the goals of

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

25

Delgado and Strawn

psychotherapy outlined and agreed upon by both parties at the beginning of the psychotherapy. Importantly, however, termination is viewed differently in many of the commonly used forms of nonpsychodynamic, time-limited psychotherapy (e.g., IPT and CBT). In these therapies, session frequency and duration of treatment are often defined at the time of initial contract. Moreover, these therapies vary in the degree to which the termination process becomes explicitly part of the therapy. For example, in IPT, Weissman and colleagues (2000) recommend that termination should be discussed at least two to four sessions before it occurs (p. 117). The recognition of the loss of the therapeutic relationship, especially as it relates to the patients competence, acknowledgment of grieving, and recognition of the patients new competence are central to the process of termination in IPT. In addition, when terminating IPT for adolescents (IPT-A), it is critical that the family be involved. In fact, some texts recommend that during the termination of IPT-A, the final session should be a family session in which the following are reviewed: (1) presenting symptoms, interpersonal disputes; (2) problems and goals of the therapy; (3) achievement in therapy; and (4) family interactions and functioning (Weissman et al., 2000). Similarly, several cognitive therapy texts (A. Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; J. Beck, 1995), after emphasizing the importance of preparing the patient for termination, note that the termination phase allows for gains to be consolidated and strategies to be generalized. Beck et al. (1979) also astutely note that a patient may have a myriad of feelings and affective responses during termination, which range from anger to sadness. Cognitive therapists suggest that these feelings should be addressed by using a limited reflective process, and that the educational nature of the treatment should be emphasized and that any positive transference reactions [should be] discouraged (A. Beck et al., 1979, p. 317). In cognitive therapy, tapering of psychotherapy has been recommended such that the therapist may begin seeing the patientwho had previously been seen weeklyon an every-other-week basis, after which the therapist might see the patient monthly (J. Beck, 1995). However, some cognitive therapists also recommend booster sessions approximately 3, 6, and 12 months following termination. In the

26

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

termination of cognitive therapy, the exploration of automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions related to termination is of importance (J. Beck, 1995).

The termination process and its complexities

When the process of psychotherapy is well established, many difficult topics and questions begin to arise in the therapists mind related to when and how to make the decision to terminate with the adolescent:

When does the adolescent begin to think about termination? The process of termination occurs over time, and evenly hovering attention (S. Freud, 1912/1958; p. 111) is required as the therapist listens for early signs that termination is being considered by the adolescent. The most common sign suggesting that the adolescent is beginning to think about termination is when he or she begins to wonder if the frequency of the sessions can be reduced due to his or her improvement. Statements during the early phase of termination may reflect actual improvement (e.g., Im doing better) with altruism (e.g., I dont have much to talk about and you can use this hour for other teens that need it more) and might imply recognition that the psychotherapy has been helpful. In addition, the adolescents statements may suggest sublimation by thinking about the therapists feelings regarding termination. The adolescent begins to share the ambivalence and dilemma in feeling better although not being ready to end the therapeutic relationship with the therapist.

Adam, a 15-year-old boy, was involved in psychotherapy for 2 years for social inhibition and multiple somatic symptoms that prevented him from interacting with his peers. After these 2 years, he called his therapist from high school to say, I cant make it to the appointment today, Im going to get together with friends to finish a project on recycling energy at school. He added, with feelings of independence, I hope it doesnt hurt your feelings, but I know you would agree this is good for me, and ended with ambivalence, right?

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

27

Delgado and Strawn

Adolescents who have a history of significant losses in their lives may struggle and fear the mourning process and may begin to skip sessions, or at times may allegedly forget sessions. When the therapist openly discusses the possible link between these aspects and the adolescents past losses, the adolescent may express some remorse about missing the sessions and may experience guilt that his or her independence elicits the letting go of the therapist. Therefore, the therapist may want to serve as a transitional object (Sugarman, 2010; Winnicott, 1953) and allow the adolescent to feel reassured that the loss need not be permanent and that the adolescent should feel free to return to psychotherapy if necessary. At other times, the adolescents ambivalence can be seen as a counterphobic reaction and there may be expressions of anger at the suggestion that the missed appointments could have meaning. In addition, there may be a regressive pull related to a hope that the therapist will not agree with the adolescents progress, which will enable the adolescent to reestablish a dysfunctional pattern and allow him or her to avoid asserting competency for fear of injuring the therapist or parent. It is best to allow this back-andforth flow, similar to a reworking of the rapprochement process, until the adolescent can tolerate that the therapist was able to contain his or her fears without losing confidence in the adolescents accomplishments (Furman, 1973). As long as there is evidence that the adolescents interplay with family, school, and peers has improved, termination should be brought to the attention of the adolescent to begin the process in which ownership of the independence of continued work on future problems can continue without the repetition of early dysfunctional patterns and without the therapist.

Does termination have to be planned? In psychodynamic psychotherapy, there is no universal approach to termination or to the planning of termination that will be effective for all cases. The creative element of art that the therapist brings to the psychotherapy process is influenced by the color of the paints used by the adolescent on the canvas created by both patient and therapist in their relationship. It is therefore impor-

28

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

tant to base the decision to terminate upon when the artwork has been completed by all partiesadolescent, therapist, and parentsand when all parties agree that the criteria for termination have been met: improved capacity for love, work, and play. Some adolescents are more psychologically minded, make progress, and develop insight and self-reflective capacities with comfort. This will facilitate the termination process as a joint decision with a sense of loss and finality. The planning of the termination phase is illustrated in the following vignette, which describes the therapists consideration of a number of internal and external factors and highlights the time course of termination.

Ryan, a 17-year-old high school senior with major depressive disorder (DSM-IV-TR criteria), was referred to psychodynamic psychotherapy after a near-lethal suicide attempt. While an inpatient on the adolescent psychiatric unit, he expressed remorse and wished to understand his depression. He was able to relate, Im depressed, even though I have a lot going for me. He had a relatively brief admission and demonstrated good ego strengths in recognizing that he had become overwhelmed by the rigidity of his expectations; he wanted to be the best in school and soccer. Ryan was a likable, athletic adolescent who began psychotherapy enthusiastically, although he initially treated the process as an intellectual exercise. He immediately began to show his motivation in psychotherapy by flaunting his knowledge of what he needed to work on. He clearly felt this would help him be liked by his therapist rather than allowing himself to be seen as a troubled adolescent with serious conflicts that prevented him from being genuinely happy. His intellectual exercise, in attempting to connect with his therapist, did not permit any awareness of his tendency to maintain distance by outsmarting and outwitting others (e.g., his therapist). Initially, he spoke of his accomplishments and was puzzled by his chronic sense of failure. The brief periods during which he seemed sad and lonely were quickly hidden. Thus, these uncomfortable aspects of himself were covered with the veneer of a confident and popular young man. In the face of his own unhappiness, he seemed to perpetually struggle to keep others (i.e., representations of early objects in his life) happy. He would ask his therapist how he might help his friends as well as a girl whom he had started dating who

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

29

Delgado and Strawn struggled with anorexia and often cutthings for which Ryan felt a sense of responsibility. Nevertheless, during this opening phase of psychotherapy, Ryan would feel that any comment the therapist made had already occurred to him. Countertransferentially, this tendency often frustrated his therapist, mirroring the feelings his parents also had. Ryans parents were seen in individual sessions every 4 weeks and concurred with this sense of frustration: He thinks he knows it all, but hes unhappy. Gradually, as the middle phase emerged, comments about transference issues were more recognizable to Ryan. For example, he would become concerned for his therapists well-being, stating, You seem tired, not feeling well, being sick or working too much. Although he seemed genuinely worried, when the therapist, who did not feel tired, would reflect and wonder about why the worry, Ryan shared that he saw the therapist as frail. Ryan feared telling the therapist about being angry that he, the therapist, was not helping him, since he had not been able to talk about the events that led to his suicide attempt. After several sessions, the patient recognized that he wanted to be forced to talk about his depressive feelings because he could then believe they were outside of his awareness. Over the course of the first half-year of treatment, the therapist helped Ryan to become aware that he was keeping the therapist at a distance with a wall of obsessional intellectual capacities to avoid experiencing his own ambivalence about working through his depressive feelings. The therapist reflected that it would not be uncommon to fear that taking care of himself would force him to give up being only super Ryan. Over time, Ryan was able to speak about his anxieties and depressed self in a sophisticated manner and would at times fear that he would be experienced by the therapist as selfish for being able to not rely on you as much. As Ryan continued to make substantial progress and appear consistently happier, the therapist recognized that the early phase of termination had begun. Ryan shared events of his life that generally reflected an adolescent who was freer from his internal unrealistic expectations. He was more spontaneous and less inhibited by the fear that he might disappoint others or his therapist. He began to contemplate ending his psychotherapy, initially as a practical is-

30

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy sue, when he began to work after school as a server at a high-end restaurant. He continued to develop a capacity for self-reflection and became more tolerant of his own ambivalence in relationships with peers. He tolerated comments by his therapist and was surprised that his therapist could actually be happy for him. Several weeks before his graduation from high school, Ryan had been accepted to nearly every college to which he had applied, and he also had begun to occasionally smoke cigars (identification with his father, who also smoked cigars, something his mother vehemently disapproved of and which was the focus of one of the parent sessions). Ryan worked in the sessions, stating he knew that smoking was unhealthy but I just want to know I could make my own mistakes and be a little rebellious. He added, I also like when my mom gets mad when I act like my dad, although Ryan was aware his mother cared for him. Ryan was able to feel confident that his therapist would understand his wish to be a rebellious adolescent without serious regression or acting out within the context of loosening the parental ties (Blos, 1967) and the reworking of his second individuation of adolescence. His ego strengths helped him to recognize his actions as rebellious to the parents, as well as allowing his identification to his successful, married father. In addition, he had begun to date a bright cheerleader who despite being 2 years younger was more sexually experienced. He spent the last three sessions reflecting on how his prior inhibitions had affected his own fear of sexuality, but he was happy that his girlfriend was smart, hot, and cares about me, suggesting a resolution of his early ties to his mother.

For other adolescents who, despite significant improvement, may continue to exhibit remnants of anxious or avoidant attachment styles, the therapist will need to provide more approval and guidance, review the goals achieved, and in doing so will encourage the adolescent to feel the sense of accomplishment and to accept termination. Thus, the adolescent will be better able to tolerate the feelings of loss without experiencing the end of the psychotherapeutic process as abandonment. With such adolescents, the freedom to come back for refueling sessions may be necessary and bears a similarity to the booster sessions commonly used in brief psychotherapies such as CBT (A. Beck et al., 1979, J. Beck, 1995). Finally, some adolescents who struggle with cognitive

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

31

Delgado and Strawn

limitations and concrete capacities may require the therapist to be more active in promoting the adolescents understanding of others intentions and motives, and termination may not be indicated. As such, maintaining continuity with a benign object is important, and the transfer to another therapist, when necessary, may allow the adolescent to continue with a supportive psychotherapeutic process. The length of the termination process will vary according to the circumstances unique to each adolescents needs. In classic psychoanalytic theory, termination is based on arbitrary matters. Some feel that for a successful working through, 1 month should be spent in the termination phase for every year of psychoanalysis (Gabbard, 2009). Others believe that termination should be discussed for several months, after which, if agreed, 4 months are needed for the working through of the transference neurosis (J. C. Hirschberg, personal communication, 1987). We propose that in contemporary psychotherapy the time dedicated to termination should be based not only on the achievement of the criteria for termination, but also on the permanency of the achievements. As stated earlier, depending on the innate ego capacity of the adolescent, the termination process may occur over months or weeks, and some adolescents may benefit from continuing this process for an extended period of time.

Should a termination date be set? Can this be changed? Flexibility is needed when considering a termination date. When a date has been set and has been agreed upon by all parties, the termination process will unfold in a manner that is unique to each adolescent. For example, when there are brief periods of regression, such as when the adolescent feels youre kicking me out, a reawakening of early childhood conflicts as part of working through the loss of the therapist may be evident, and it would be best not to change the date. Accordingly, the therapist may reflect the ambivalence related to being left to handle matters independently. Such is the case with Adam, the 15-year-old boy with social inhibition and anxiety described earlier:

32

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy In the last three sessions of his therapy, Adam began to show increased anxiety and would say, Im not cured, I still worry. This was interpreted as his fear that the therapist was not confident the patient could handle things on his own. Surprisingly, Adam shared I needed your reassurance, laughed, and said, You better be worried, my life is not perfect but can be fun. I really do thank you for what you did for me.

If the regression is severe and complicated by a prolonged worsening of the patients functioning and fails to respond to an open discussion about what has occurred, a new date should be set, with more time for processing deep-rooted issues of loss and feelings of abandonment. By changing the date without losing sight of the need to work through issues of dependence, the therapist models both the capacity for reflective functioning and the capacity to keep in mind that, at times of loss, old patterns may be reawakened.

Mary, a 17-year-old girl, began treatment for a myriad of self-defeating behaviors and made remarkable progress during the course of 2 years of weekly psychotherapy. When a termination date was set, she regressed and had a serious escapade where she became intoxicated and experienced urges to inflict cuts on her arms. Her therapist interpreted these urges as the reawakening of her early feelings of being alone, which she felt would occur if she were to be without her therapist. She angrily replied, How can you do this to me when I am out of control? After this response was processed, it became clear that it reflected her need to test both her own and her therapists view of her improvement and mastery that had occurred during the last 3 months. She said, You have been the only person that has shown me how to handle ugly feelings inside. How do you do it? Needless to say, the termination date was delayed to further allow her to mourn and forgive herself for acting out the regressive pull of her conflicts. She became actively involved in support groups for teens with substance abuse, stating: That will be my new therapy!

Lastly, the termination date may need to be changed when circumstances that are out of the control of the adolescent and the

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

33

Delgado and Strawn

therapist infringe on the termination process. Such circumstances include medical illness, loss of insurance, and so on. Who decides if problem-solving skills are adequate? What if there is a split decision? It is not uncommon for the adolescent patient and the therapist to agree on the improvement made and readiness for termination, although the adolescents parents may have a much different opinion. Frequently, the parents reluctance may relate to their own fears of being abandoned by their adolescent or by the therapist, which will need to be addressed so that these fears do not interfere with the adolescents achievements. Certainly, psychotherapists working with children and adolescents have, for many years, appreciated that young patients may be greatly improved by treatment with their symptoms persisting, or conversely, childrens symptoms may disappear without the child being cured and that, in some cases, parents may be primarily aware of the manifest symptomatology (A. Freud, 1971, p. 10). Thus, careful attention should be paid to the parents reluctance to terminate the psychotherapy. When the parents reluctance is based on facts that the adolescent has not shared with the therapist, the therapist may have colluded with the adolescents excitement. The adolescent may unconsciously attempt to please the therapist by sharing only successful matters, even though he or she is not psychologically ready for termination. The adolescent may have been unable to tolerate the necessary individuation and mourning process, and he or she may have been acting out in the form of regressive self-defeating behavior or aggression with family or peers. Such a scenario is illustrated here:

Andrea, a 14-year-old girl with feelings of sadness following her brothers transition to college, began psychotherapy by describing her brother: He was my soul mate. She was also overwhelmed by her parents anxiety and intrusive behavior (i.e., their displacement, onto their daughter, of their own anxiety about their son having left home even though Andrea was a perfect teenager with good grades.) After 2 years of twice-weekly psychotherapy,

34

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy Andrea was happier and continued to hold honor roll status; she was now employed and had begun to date a well-liked peer. As termination was being planned, her parents called to schedule an urgent appointment. They informed the therapist that Andrea had been abusing pain medication and had been inflicting cuts on her legs where nobody could see them. When this was addressed with Andrea, she commented, You seemed so happy that I was doing well and I didnt think you (i.e., parental transference) could handle my rebelliousness and not being as good as my brother. The therapist sought consultation and was able to recognize the countertransference issues that had precluded successful termination. The termination process was postponed to help the patient work through her fear of feeling successful with awareness of her strengths and weaknesses.

Is working through a transference neurosis necessary? It is generally agreed that the working through of the transference neurosis is relevant to classical forms of psychoanalysis (Ferenczi & Rank, 1925; S. Freud, 1912/1958). Accordingly, the curative aspects of the treatment rely on the neutrality of the analyst to allow for the development of a transference neurosis, after which, through a process of transference interpretations, the unconscious conflicts are made conscious (i.e., where id was, ego shall be), developing insight that may lead to character changes (S. Freud, 1912/1967b). However, the existence of a transference neurosis in adolescents has been controversial (Blos, 1979; Chused, 1988; Novick, 1976, 1982). For example, Peter Blos (1979) argued that the transference neurosis cannot be formed until the end of adolescence, while others have suggested that the proximity of the adolescent to his or her primary objects makes the development of a transference neurosis difficult (Chused, 1988). However, psychodynamic psychotherapists working with adolescents increasingly appreciate that the concept of the transference neurosis may need to be redefined as an intensification of pathological character traits and modes of relating, [and the] gradual emergence of regression, fantasies, conflicts and impulses (Chused, 1988, p. 52) that the adolescent patient experiences in the relationship with his

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

35

Delgado and Strawn

or her therapist (Chused, 1988; Novick & Novick, 2006). Importantly, in the current practice of psychodynamic psychotherapy, transference issues are attended to as they emerge; the process no longer relies on absolute analytic neutrality. Rather, the therapist is active in co-creating the necessary therapeutic space with the patient to maintain the ebb and flow of the relationship and to maintain an openness to discussing distortions that are influenced by the patients past object relations (Dewald, 1982).

Is weaning the psychotherapy best, or would a trial period without psychotherapy be better? The suggestion that before termination in adolescent psychotherapy, the patient undergoes a trial period without psychotherapy1 to 2 monthsversus a period of weaning the psychotherapy process has generated significant discussion over the past several decades. Other models have suggested that the adolescent may periodically return to therapy (Van Dam, Heinicke, & Shane, 1975). However, despite this attention, there are no clear data as to the superiority of one approach over the other. Weaning the psychotherapy usually occurs by decreasing the frequency of the appointments (e.g., from weekly to every other week to monthly). In general terms, weaning can be very useful for some adolescents if they are involved in new activities related to the accomplishments made during psychotherapy. Weaning allows time for the adolescent to summarize and review, with a sense of pride in what has been achieved together with his or her therapist during treatment. Similarly, trial periods without psychotherapy may be helpful in some circumstances (e.g., summer camps, illness of family member, family moves). However, it is best for the therapist to remain available during these times to help the patient, and to begin a formal termination process upon the adolescents return, rather than a final session to say good-bye after an extended period of time. Of course, inevitably the adolescent will have opportunities for trial periods without psychotherapy when the therapist is absent for personal or business reasons, which provides a glimpse of the adolescents readiness for termination. Importantly, the attachment style of the patient needs to be considered in deciding how the trial without psychotherapy should

36

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

be conducted. An adolescent who views and experiences relationships through the lens of a secure attachment may benefit from terminating the psychotherapy without weaning, as he or she has managed to internalize healthy relational patterns. The adolescent who struggles with anxious or avoidant attachment styles will benefit from a gradual weaning process to practice holding in mind what was learned in the sessions. To this end, even those adolescents who repeat insecure attachment patterns with their parents may independently form meaningful peer relationships and intimate relationships (Allen & Land, 1999). However, psychodynamic psychotherapists terminating with adolescents would do well to remember that the patients early attachment patterns (Bowlby, 1969) are likely being further integrated and reshaped throughout adolescence (Stortelder & Ploegmakers-Burg, 2010).

During extended absences, should therapy continue by phone? As stated earlier, an extended absence from psychotherapy is not uncommon, especially as adolescents attend summer camps, celebrate holidays, or matriculate to college. In many cases, the events that precipitated the extended absences (e.g., attendance at sports camp or college) had not been possible before treatment. The therapist who wishes to share in the success of the adolescent (countertransference excitement) may be prone to agree to continue the psychotherapy by phone during the absence. In any agreement to continue psychotherapy by phone, a careful discussion must occur with the adolescent and his or her parents about their expectations and the frame about the goals and scheduling of the phone calls. In addition, it is important to clarify professional licensure requirements if the camp or college is out-ofstate. If the process has already entered the termination phase, it seems reasonable to allow phone appointments for a successful transition, as long as they are supportive in form. In the case of a summer camp, it is expected that the adolescent will return to psychotherapy and the time at camp is used as a trial to assess the readiness for termination. In the case of college, a careful decision will need to be made about whether to officially terminate

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

37

Delgado and Strawn

or to facilitate the adolescents starting psychotherapy in the new environment. Finally, an adolescents accomplishments may reawaken the therapists own adolescent conflicts. In a less successful outcome, the therapist may unconsciously be unable to tolerate the adolescents accomplishments and decline to be available by phone. In such instances, the therapist might carefully reconsider his or her availability by phone or, if in training, might raise the issue in supervision. .

When there is need for a forced termination, should the adolescent be transferred to another clinician? Forced terminations occur with increasing frequency in training programs (as a result of graduation) and as a result of managed care limits on the duration and frequency of treatment (Bostic et al., 1996; De Bosset & Styrsky, 1986). If this occurs during the termination phase of the psychotherapy, a transfer may not be necessary. In supervision, what is in the best interest of the patient should be discussed. For some, the time for a forced termination may come when the patient has accomplished a number of his or her goals; in these cases, it may be best to leave the door open such that the patient could return to psychotherapy with the former therapist, if available, or with a new therapist at a later date. However, some psychodynamic therapists have recommended that transfer be framed as a choice for the patient (Bostic et al., 1996). If the psychotherapy is in the early or middle phase of the treatment process, the termination is best classified as a forced termination, and it is generally helpful to facilitate a transfer of the patient to a new practitioner by introducing the new therapist several sessions before the final session to allow for discussion about the feelings of being abandoned and the feelings toward the new therapist. In addition, the transfer should be to a practitioner with similar beliefs regarding psychodynamic psychotherapy so as to avoid an abrupt shift to a different form of psychotherapy and risk sudden, premature termination by the adolescent or his or her family.

38

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

How is payment discussed if the adolescent patient is transferred to another clinician upon termination? In recent years, some adolescents and their families are not charged for psychotherapy sessions with residents or trainees due to federal grant funding at certain institutions.There are also regulations that prohibit collecting fees from patients because it is considered double payment to the academic training center. Thus, after the trainees graduation, if the psychotherapeutic process with the adolescent is to be continued, significant complicating factors may arise. For example, if during the termination phase there are reasons the psychotherapy cannot be continued with a trainee, a discussion with the supervisor will facilitate a decision as to what is in the best interest of the adolescent. Typically, if financially feasible, a referral should be made to the trainees departments outpatient service or to a local practitioner. Similarly, when the former child and adolescent psychiatry residents or trainees continue to work in the academic setting, the low-fee case will also need to be discussed with the department director because it may affect the newly minted clinicians productivity. When the graduating trainee joins a local private practice group, clear negotiation of the fees will need to be thoroughly discussed. Supervisors can help graduating residents understand that continuing with a case during the termination phase due to feelings of countertransference guilt (I would like to finish because he (or she) is so attached to me) may be detrimental. For example, the adolescent patient may express his or her anger at (1) having to pay for sessions, (2) having to travel to a new office, or (3) feeling inferior to private paying patients. Moreover, the adolescent may miss appointments without notifying the therapist or may miss payments to the therapist. This, in turn, may stir feelings of resentment in the therapist toward the adolescent and the parents because the therapist is subsidizing the case, causing the therapist to abruptly terminate the process. Should the therapist accept the patients good-bye gift? Frequently adolescents and their parents are grateful for the work accomplished with the therapist. At times they demonstrate their

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

39

Delgado and Strawn

gratitude in the form of a gift; accepting such a gift is reasonable if it is a small gift with limited monetary value. Nevertheless, the therapist may recognize from the content of the sessions before termination that the gift may also represent the patients unconscious wishes for reparation of the many negative feelings that were tolerated by the therapist during the process or the patients conscious wishes to be remembered. In general terms, it is best to accept the gift without disruption of the successful achievements toward autonomy and independence demonstrated by the adolescent during termination, because the therapist no longer has the opportunity to help the adolescent reflect on the possible meanings the gift may have. Furthermore, in some cultures gift giving is a common practice to show gratitude, and rejecting the gift may be perceived as an insult (Sue & Zane, 1987). When the gift is of a value that is beyond the norms of gratitude and leaves the therapist with feelings of discomfort without time to process, it is best to find a way to sensitively decline the gift. The following vignette illustrates how the therapist declined a gift and also helped the family reflect on the psychological value rather than the financial value of the therapy.

After 18 months in psychotherapy, Brian was ready to terminate therapy and attend an Ivy League school. During the last session, he and his parents brought the therapist a gift card to cover the cost of dinner for the therapist and spouse at a local fine dining restaurant. The therapist declined the gift and helped the family consider using the gift card to celebrate the work their son had accomplished or to donate the value of the gift to a charitable organization that benefited children. They opted for the latter. Thus, it is the thought that counts can be used to maintain a professional stance.

Countertransference aspects of termination

Countertransference, the therapists unconscious subjective experience influenced by the patients transference, is of central importance in psychodynamic psychotherapy (S. Freud, 1910/1967). This process helps the therapist understand the adolescent patient

40

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

within the context of his or her intersubjective and relational experiences, and is a valuable tool that informs and steers therapeutic interventions (Schowalter, 1985; Sugarman, 2010). However, countertransference in the termination phase of psychotherapy with adolescents may uniquely challenge the therapist and may resonate with the therapists experiences of turmoil during adolescence. For those therapists in supervision, an understanding of the necessary countertransferential aspects of the treatment and how he or she will use these aspects is critical. Specific potentially problematic aspects of countertransference that may emerge during the termination phase of treatment are explored here.

Colluding with the adolescents dependency, the therapist is perceived as permissive by the patient or parents During the termination phase, when the therapist does not recognize he or she is being permissive in readily agreeing with the adolescents rationalizations about his or her values vis--vis the environment, the patient and the parents will experience the therapist as being dismissive of the current conflicts and of having low expectations for improvement or change. This is particularly important regarding academic failure, substance abuse, and sexual activities. A common example occurs during the termination phase, during which the adolescent has improved in most areas but begins to miss some academic deadlines, occasionally abuses illegal substances, or is insensitive to peers anxieties. The therapist may accept these behaviors as compromises and not address the continued self-defeating behavior. In short, the therapist may understand these aspects of the adolescent as regressive behavior that will improve over time. This usually occurs when the therapists own struggles during adolescence lead to unconscious competitive feelings that in turn promote the adolescents dependency. The therapist fears letting go of the patient When the adolescents anxiety about terminating is paralleled by the therapists anxiety in letting go of the successful patient, the termination process may be unnecessarily lengthened. The therapist may ignore the comments made by the adolescent that are

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

41

Delgado and Strawn

relevant to termination, so as to avoid considering the loss of the healthy patient, and may instead perceive that the treatment has not helped the adolescent achieve a perfect life. In addition, the ending of psychotherapy with the adolescent who has done well in treatment will be a time of sadness and mourning for the therapist (Galatzer-Levy, 1991). These feelings of sadness, as well as a number of countertransference-based fears, are illustrated in the following vignette, which describes the termination phase of psychotherapy with Ryan (described earlier), a 17-year-old boy who began treatment following a near-lethal suicide attempt:

During the termination phase of Ryans psychotherapy, his therapist initially had fears that the accomplishments of therapy would not persist and often seemed to search for clinical or process data that would confirm or refute the permanence of Ryans relational changes or the stability of these changes. With consultation, it became clear that the therapist was unconsciously remembering Ryans early suicide attempt, which had occurred while he was superficially happy, which was not the case in Ryans current healthier self. As Ryan became more spontaneous and began to have intimate relationships, smoke, and occasionally drink, his therapist experienced a sense of apprehension and in some ways shared Ryans mothers concern: Did I overshoot? Also, as Ryan became more mature and less inhibited, he would sometimes flaunt his spontaneity, his relationship with his girlfriend, his teenage escapades of playing paintball late at night, and his fantasies and excitement about leaving for college. At times, these aspects elicited a sense of envy on the part of his therapist. Lastly, his therapist worked through the loss of the healthy patient that would come with termination and mourned his curiosity regarding Ryans future development.

The therapist expresses frustration by minimizing expectations Some adolescents with character disorders may have a long history of being demanding and argumentativea pattern that creates distance from others for fear of feeling close and being engulfed. In these individuals, the therapist may minimize the expectations for improvement and may rush treatment to an abrupt end or a forced termination rather than tolerating the temporary fury of

42

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

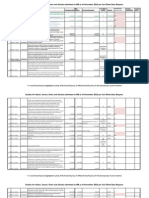

Table 1. Elements present when adolescent begins to consider termination Element Statements about the therapist or psychotherapy Examples Ambivalence or a decreased investment in the treatment For example, the adolescent is comfortable reflecting in sessions on the decreased need of the therapist: I dont have much to talk about, I did fine during on vacation, etc. Statements about loss Sublimation1 The adolescent speaks about managing conflict with parents and peers. Introduction of more material from reality, suggesting healthy, decreased investment in the treatment1 Internalization of the therapist2 The adolescent speaks about what he or she has learned in psychotherapy: I know what you would have said. Greater capacity to tolerate negative affect Improved capacity to hold and to tolerate conflicting affects Empathy with peers1 Humor1 The adolescent may use of humor in jokingly jabbing therapist about personal matters (e.g. office dcor, clothes, age). Increased self-reflective capacity Increased flexibility of defenses1 Improved adaptiveness of defenses1 Shifts toward more mature defenses Sustained improvement in symptoms The adolescent may share how he or she successfully handled unrealistic expectations or demands from his or her parents. Flaunting of accomplishments (e.g., academic knowledge, grades, awards, sports, dating experiences, beginning a job) Resumption of age-appropriate sources of enjoyment The adolescent is able to reflect on dreams Sustained decreases in interpreting resistances1 Conversation flows and therapist makes fewer comments, thus allowing the patient to discover his or her own insights. Sadness Envy Ambivalence Excitement

Note. Psychodynamic psychotherapists should pay particular attention to these elements both in the psychotherapeutic process, which largely reflects relational and intrapsychic aspects of the adolescent, and in the accounts of the young patient's external world. Adapted from Kernberg, 19911 and Smirnoff, 19712.

Affect Insight

Defenses Symptoms

Play and dreams

Therapist interventions

Countertransference

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

43

Delgado and Strawn

the negative transference, a necessary step in the promotion of self-reflection. In the treatment of such adolescents, the therapist may also feel defeated and that the case was not a good referral or that another form of psychotherapy would have better served the adolescent. At the extreme, the therapist may become frustrated and identify with the patients projectionsprojective identification(Klein, 1946), feeling that the patient was not treatable.

The therapist admires the adolescents achievements for narcissistic reasons Healthy mourning of the adolescents former dependence by both the parents and the therapist is part and parcel of a successful termination process. Thus, tolerating, admiring, and encouraging the adolescents achievements is understandable as part of the process of mourning. However, when the therapist is affected by personal narcissistic needs rather than respecting the patients decision to flaunt the wish for recognition of their progress (e.g., I am quitting), the therapist feels rejected and may make comments like you seem to feel youre ready to quit; it would be best if we can take more time to review the progress we made together, hoping for the patient to acknowledge the therapists importance. Should the therapist give the patient a good-bye gift? When the therapist has assumed the role of a transitional relational-object, it may be appealing to turn this role into a concrete object in the form of a gift (Levin & Wermer, 1966). The authors are indebted to Dr. Cotter Hirschbergs (personal communication, 1987) advice in these situations: The gift you give your psychotherapy patients is your interest in them. You have taught them that their gift to you is thinking about you when they need to. The role of parents in termination

The unique role of parents in the psychotherapeutic work with children and adolescents has been recognized and written about

44

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

extensively for nearly half a century, although most of this work has focused on the early stages of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy (Altman, Briggs, Frankel, Gensler, & Pantone, 2002; Sperling, 1997). Surprisingly, little has been written about parental participation and the role of parents during the termination phase. Therapists working dynamically with child and adolescent patients are often acutely aware of aspects of the parents unconscious, including jealousy, envy, competition, idealization, and potential guilt related to needing to seek treatment for their child, which may affect the psychotherapy and alliance. Therefore, most psychodynamic psychotherapists will maintain regular contact with their patients parents over the course of treatment so as to: (1) monitor treatment, (2) remain appraised of changes in the parental relationship, and (3) understand the parents reactions to the changes that occur in the adolescent as a result of the psychotherapy (Sperling, 1997). Importantly, this regular contact allows the parents to support the treatment and the therapist to support the parents, particularly during challenging times (Sperling, 1979). With regard to the ending of treatment, many child and adolescent therapists have idyllically imagined the successful termination as an agreement by all parties (parent, patient, and therapist). However, Anna Freud (1971) noted nearly 50 years ago, in presenting data from the Hampstead Clinic, that the agreement of all three parties was rare and occurred in only 33% of cases. Termination may also evoke secondary reactions from the adolescent toward the parents. One common reaction is the adolescents wish to distance from parental input about decisions, particularly about termination. Peter Blos (1967), in his seminal paper, The Second Individuation Process of Adolescence, suggested that adolescents would necessarily go through a phase of working through the intrapsychic pressures to loosen the libidinal ties to their parents, and that, when successful, this process would be accompanied by an experience of autonomy without fear of feeling alone. Moreover, we have often heard the unconscious, counterphobic question: Why did I have to change and not my parents? Such questions need to be addressed as part of

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

45

Delgado and Strawn

the patients ambivalence and should reflect that changes in the adolescent did in fact lead to changes in the parents. In these situations it is helpful to discuss the parents role in supporting the termination and to recognize the adolescents improvement, with realistic expectations for the future. The adolescent will need help in giving credit to his or her parents and in acknowledging that there have been changes at all (Hirschberg, 1977; Schwartz, 1974). The parents may, at times, struggle with their own narcissistic needs and demand joint sessions, wanting the adolescent to admire them for their sacrifice in allowing the treatment to occur. Finally, the feeling of no longer being needed or being given up as a narcissistic object may accentuate ... personal feelings of loss for some therapists (Goldberg, 1975, p. 699). Almost certainly, there will be difficulties with some parents during the termination phase, which may parallel the countertransference reactions of the therapist. For example, parents may collude with the adolescents fear of saying good-bye or with the patients feelings of sadness about the loss of the therapist. That is to say, the parents may be unable to acknowledge: We actually needed you and you were helpful. Other parents may experience an empty nest syndrome (Krystal & Chiriboga, 1979) and may wish to pursue treatment with their adolescents therapist after the termination. It is best not to begin a therapeutic relationship with the parents because if the adolescent wishes to return for treatment at a later date, he or she may fear that the therapist can no longer have an objective view of the adolescents issues. However, in some cases in which the parents need help with the mourning process in letting go of their adolescent, several parent sessions following termination may be helpful as long the adolescent is informed about the goals. Again, we return to the case of Ryan, but this time we focus on his parents reactions to the termination phase, which parallels the countertransference experienced by his therapist.

Like his therapist, Ryans parents also worried that the accomplishments Ryan had made in psychotherapy would not persist, and they also experienced a degree of sadness around the loss of the therapist. Ryans parents were intensely curious whether their sonif need bewould be able to return to see his therapist. 46

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

Table 2. Criteria for termination in adolescent psychotherapy Resolution of symptoms Modification of the ego to resume normal forward psychological development Stable relationships with parents and peers Tolerance of painful affects by sublimation rather than denial or more primitive defenses Capacity to love and forgive Capacity to use humor with reciprocity Capacity to feel enjoyment of academic and employment activities Capacity to accept strengths and weakness in realistic terms

Ryans mother would anxiously ask, Do you think youll ever move away? How much longer will you live here? Importantly, although these questions were directed at the therapist, it suggested that the young therapist had also served as a representation of their now mature son. In addition, as his parents began to see their son as a more carefree young man who had begun to occasionally smoke cigars and play paintball late at night with friends, his parents asked, Did you overshoot? but quickly thereafter acknowledged that their son seemed truly happy. Last, given the circumstances that had precipitated his suicide attemptat a time when he was seemingly successfulRyans parents appropriately worried that they might again miss something. They were reassured by examples of the significant changes that their son and they had made during the course of the psychotherapy.

Conclusion

Termination in psychodynamic psychotherapy, relative to termination in other types of therapy commonly used with adolescents, such as CBT, DBT, and IPT, is a process that requires active dialogue between all parties (i.e., parent, adolescent and therapist). In this exciting phase of treatment, during which the adolescent and his or her parents end a therapeutic relationship, a number of changes may have become apparent in the inner world of the patient as well as in the outside world (e.g., improvement in symptoms). The course of healthy psychological development has reVol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

47

Delgado and Strawn

sumed, the work of psychotherapy has been integrated, and the symptoms that originally brought the young patient to treatment have abated. The astute therapist will carefully examine statements about the psychotherapy (or therapist) and will carefully note changes in affect, insight, defenses, play, and dreams that may signify readiness for termination (Tables 1 and 2). However, it is critical that the psychodynamically informed psychotherapist also consider his or her own countertransference, which may either facilitate the inappropriate continuation of therapy or may result in the premature termination of the treatment. Lastly, despite the limited attention it has received in the extant literature, the role of parents in the termination process is of paramount importance. In working with parents, the successful therapist will need to remain aware of aspects of the parents unconscious that may affect termination (e.g., jealousy, envy, competition, idealization) and be cognizant of the parents possible collusion with the adolescents fear of saying good-bye or the sadness about the loss of the therapist.

References

Abrams, S. (1978). Termination in child analysis. In J. Glenn (Ed.), Child analysis and therapy (pp. 451-470). New York: Aronson. Allen, J. P., & Land, D. (1999). Attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Schaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment theory: Research and clinical implications (pp. 319335). New York: Guilford. Altman, N., Briggs, R., Frankel, J., Gensler, D., & Pantone, P. (2002). Relational child psychotherapy. New York: Other Press. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press. Beck, J. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press. Bleiberg, E., Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1997). Child psychoanalysis: Critical overview and a proposed reconsideration. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 138. Blos, P. (1967). The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 22, 162186.

48

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

Blos, P. (1979). The adolescent passage. New York: International Universities Press. Bostic, J. Q., Shadid, L. G., & Blotcky, M.J. (1996). Our time is up: Forced terminations during psychotherapy training. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 50, 347359. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books. Briggs, S. (2002). Working with adolescents: A contemporary psychodynamic approach. New York: Palgrave. Burgner, M. (1988). Analytic work with adolescents: Terminable and interminable. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 63, 179187. Chused, J. (1988). The transference neurosis in child analysis. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 43, 5182. De Bossett, F., & Styrsky, E. (1986). Termination in individual psychotherapy: A survey of residents experience. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 636641. Delgado, S. V., Strawn, J. R., & Jain, V. (2012). Psychodynamic aspects of adolescence. In J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 22102218). New York: Springer Science and Business Media. Dewald, P. A. (1982). The clinical importance of the termination phase. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 2, 441461. Ekstein, R. (1965). Working through and termination of analysis. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 13, 5778. Ekstein, R. (1983). The adolescent self during the process of termination of treatment: Termination, interruption, or intermission? Adolescent Psychiatry, 11, 125146. Ferenczi, S., & Rank, O. (1925). The development of psychoanalysis (C. Newton, Trans.). New York: Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company. Ferro, A. (2008). Curative factors and termination of analysis: A model of the mind (Summarized and translated by R. Teusch). Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 77, 13131317. (Original work published 2006) Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1994). The efficacy of psycho-analysis for children with disruptive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 4555. Fox, E. F., Nelson, M. A., & Bolman, W. M. (1969). The termination process: A neglected dimension in social work. Social Work, 12, 5363. Freud, A. (1958). Adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 13, 255278. Freud, A. (1971). Problems of termination in child analysis. In The writings of Anna Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 321). New York: International Universities Press. Freud, S. (1958). Recommendations to physicians practising psycho-analysis. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 111120). London: ogarth Press. (Original work published 1912)

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

49

Delgado and Strawn

Freud, S. (1964). Analysis terminable and interminable. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 23, pp. 216253). London: Hogarth Press, 1956. (Original work published 1937) Freud, S. (1967). The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 11, pp. 141151). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1910) Furman, E. (1973). A contribution to assessing the role of infantile separation-individuation in adolescent development. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 28, 193207. Gabbard, G. O. (2009). What is a good enough termination? Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57, 575594. Galatzer-Levy, R. M. (1991). Considerations in the psychotherapy of adolescents. In M. Slomowitz (Ed.), Adolescent psychotherapy (pp. 85100). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Goldberg, A. (1975). Narcissism and the readiness for psychotherapy termination. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 695699. Kernberg, P. (1991). Termination in child psychoanalysis: Criteria from within sessions. In A. G. Schmukler (Ed.), Saying goodbye: A casebook of termination in child and adolescent analysis and therapy (pp. 321337). Hillside, NJ: The Analytic Press. Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 27, 99110. Krystal, S., & Chiriboga, D. A. (1979). The empty nest process in mid-life men and women. Maturitas, 1, 215222. Levin, S., & Wermer, H. (1966). The significance of giving gifts to children in therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 5, 630652. Maholick, L. T., & Turner, D. W. (1979). Termination: That difficult farewell. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 33, 583591. Moreau, D., & Mufson L. (1997). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 97110. Novick J. (1976). Termination of treatment in adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 31, 389413. Novick J. (1982). Varieties of transference in the analysis of an adolescent. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 63, 139148. Novick, J., & Novick, K. K. (2006). Good goodbyes: Knowing how to end in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis. New York: Aronson. Plakun, E. M. (2006). Finding psychodynamic psychiatrys lost generation. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 34, 135150. Sandler, J., Kennedy, H. & Tyson, R. L. (1980). The technique of child analysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

50

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Termination in adolescent therapy

Schowalter, J. E. (1985). Countertransference in work with children: Review of a neglected concept, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 4045. Schwartz, I. G. (1974). Forced termination of analysis revisited. International Review Psychoanalysis, 1, 283290. Smirnoff, V. (1971). The scope of child analysis. New York: International Universities Press. Southam-Gerow, M. A., Henin, A., Chu, B., Marrs, A., & Kendall, P. C. (1997). Cognitive behavioral therapy with children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 111136. Sperling, E. (1979). Parent counseling and therapy. In J. Noshpitz (Ed.), Basic handbook of child psychiatry (pp. 136148). New York: Basic Books. Sperling, E. (1997). The collateral treatment of parents with children and adolescents in psychotherapy. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 8195. Stortelder, F., & Ploegmakers-Burg, M. (2010). Adolescence and the reorganization of infant development: A neuro-psychoanalytic model. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 38, 503531. Sue, S., & Zane, N. (1987). The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: A critique and reformulation. American Psychologist, 42, 3745. Sugarman, A. (2010). Losing a father all over again: The termination of an analysis of an adolescent boy suffering from father loss. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 58, 667690. Target, M., & Fonagy, P. (1994a). The efficacy of psychoanalysis for children: Prediction of outcome in a developmental context. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 11341144. Target, M., & Fonagy, P. (1994b). Efficacy of psychoanalysis for children with emotional disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 361371. Van Dam, H., Heinicke, C. M., & Shane, M. (1975). On termination in child analysis. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 30, 443474. Wallach, H. D. (1975). Termination of treatment as a loss. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 16, 538548. Weddington, W. W., & Cavenar, J. O. (1979). Termination initiated by the therapist: A countertransference storm. American Journal Psychiatry, 136, 13021305. Weis, S. (1991). Vicissitudes of termination: Transferences and countertransferences. In A. G. Schmukler (Ed.), Saying goodbye: A casebook of termination in child and adolescent analysis and therapy (pp. 265284). Hillside, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Vol. 76, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

51

Delgado and Strawn

Weissman, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., & Klerman, G. L. (2000). Comprehensive guide to interpersonal therapy. New York: Basic Books. Winnicott, D. W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena A study of the first not-me possession. International Journal of PsychoAnalysis, 34, 8997.

52

Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic

Copyright of Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic is the property of Guilford Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Psychodynamic Theory For Clinician PDFDocument219 pagesPsychodynamic Theory For Clinician PDFTitik Dyah AgustiniNo ratings yet

- ++L. Mark S. Micale, Paul Lerner-Traumatic Pasts - History, Psychiatry, and Trauma in The Modern Age, 1870-1930-Cambridge University Press (2001)Document333 pages++L. Mark S. Micale, Paul Lerner-Traumatic Pasts - History, Psychiatry, and Trauma in The Modern Age, 1870-1930-Cambridge University Press (2001)juaromer50% (2)

- Contemporary Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Evolving Clinical PracticeFrom EverandContemporary Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Evolving Clinical PracticeDavid KealyNo ratings yet

- Detailed History and Description of Transactional AnalysisDocument8 pagesDetailed History and Description of Transactional AnalysisWinda WidyantyNo ratings yet

- Fonagy P Target M 2003 Bowlbys Attachment Theory Model Ch. 10 in Psychoanalytic Theories. Perspectives Form Development PsychopathologyDocument13 pagesFonagy P Target M 2003 Bowlbys Attachment Theory Model Ch. 10 in Psychoanalytic Theories. Perspectives Form Development PsychopathologyAntonio TariNo ratings yet

- HinshelwoodR.D TransferenceDocument8 pagesHinshelwoodR.D TransferenceCecilia RoblesNo ratings yet

- On Misreading and Misleading Patients: Some Reflections On Communications, Miscommunications and Countertransference EnactmentsDocument11 pagesOn Misreading and Misleading Patients: Some Reflections On Communications, Miscommunications and Countertransference EnactmentsJanina BarbuNo ratings yet

- Glover (1928) Lectures On Technique 1Document29 pagesGlover (1928) Lectures On Technique 1Lorena GNo ratings yet

- Melanie Klein Origins of TransferanceDocument8 pagesMelanie Klein Origins of TransferanceVITOR HUGO LIMA BARRETONo ratings yet

- Karlen Lyons Ruth - Two Persons UnconsciousDocument28 pagesKarlen Lyons Ruth - Two Persons UnconsciousJanina BarbuNo ratings yet

- 2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesDocument11 pages2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesjuaromerNo ratings yet

- 1992, Meloy, Revisiting The Rorschach of Sirhan SirhanDocument23 pages1992, Meloy, Revisiting The Rorschach of Sirhan SirhanjuaromerNo ratings yet

- 2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesDocument11 pages2015, Standards, Accuracy, and Questions of Bias in Rorschach Meta-AnalysesjuaromerNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Study GuideDocument8 pagesAbnormal Psychology Study GuideMegan McDowellNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Sex Addiction: Cognitive - Behavioral TherapyDocument6 pagesTreatment of Sex Addiction: Cognitive - Behavioral TherapyDorothy HaydenNo ratings yet

- Depression Cognitive TheoriesDocument2 pagesDepression Cognitive TheoriesAnonymous Kv663lNo ratings yet

- Counseling Today Chapter 6 Power PointDocument30 pagesCounseling Today Chapter 6 Power PointHollis VilagosNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFDocument20 pagesCognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFAhkam BloonNo ratings yet

- Depression Conceptualization and Treatment: Dialogues from Psychodynamic and Cognitive Behavioral PerspectivesFrom EverandDepression Conceptualization and Treatment: Dialogues from Psychodynamic and Cognitive Behavioral PerspectivesChristos CharisNo ratings yet

- Teaching FCC To Psych - FullDocument9 pagesTeaching FCC To Psych - FullStgo NdNo ratings yet

- Case Formulation in PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesCase Formulation in PsychotherapySimona MoscuNo ratings yet

- Main 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentDocument25 pagesMain 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentKevin McInnes0% (1)

- Group Therapy Techniques Derived from PsychoanalysisDocument12 pagesGroup Therapy Techniques Derived from PsychoanalysisJuanMejiaNo ratings yet

- Fitzgerald - Child Psychoanalytic PsychotherapyDocument8 pagesFitzgerald - Child Psychoanalytic PsychotherapyJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Otto Kernberg's Object Relations TheoryDocument25 pagesOtto Kernberg's Object Relations TheoryHannah HolandaNo ratings yet

- Attachment Informed Psychotherapy: Psychotherapy With Attachment and The Brain in MindDocument147 pagesAttachment Informed Psychotherapy: Psychotherapy With Attachment and The Brain in MindKar GayeeNo ratings yet

- Fonagy - Psychoanalytic and Empirical Approaches To Developmental Psychopathology An Object-Relations PerspectiveDocument9 pagesFonagy - Psychoanalytic and Empirical Approaches To Developmental Psychopathology An Object-Relations PerspectiveJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Theories of PersonalityDocument29 pagesPsychoanalytic Theories of PersonalityAdriana Bogdanovska ToskicNo ratings yet

- Women in Psychology - Margaret MahlerDocument7 pagesWomen in Psychology - Margaret MahlerNadia ShinkewiczNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Supervision Group, IndianapolisDocument1 pagePsychoanalytic Supervision Group, IndianapolisMatthiasBeierNo ratings yet

- Object Relations TheoryDocument2 pagesObject Relations TheoryMonika Joseph0% (1)

- Kernberg. Psicoanalisis, Psicoterapias y T, de ApoyoDocument19 pagesKernberg. Psicoanalisis, Psicoterapias y T, de Apoyoalbertovillarrealher100% (1)

- A Kleinian Analysis of Group DevelopmentDocument11 pagesA Kleinian Analysis of Group DevelopmentOrbital NostromoNo ratings yet