Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aquinas God and Being

Uploaded by

Thomas Aquinas 33Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aquinas God and Being

Uploaded by

Thomas Aquinas 33Copyright:

Available Formats

Hegeler Institute

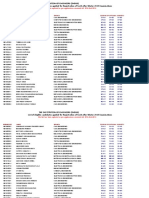

Aquinas, God, and Being Author(s): Brian Davies Reviewed work(s): Source: The Monist, Vol. 80, No. 4, Analytical Thomism (OCTOBER 1997), pp. 500-520 Published by: Hegeler Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27903547 . Accessed: 03/09/2012 23:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Hegeler Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Monist.

http://www.jstor.org

Aquinas,

God,

and

Being

At the beginning of Sein und Zeit, Martin Heidegger raises the Heidegger, Gilbert Ryle observes that,thoughsomewould quarrelwith

the assumption "that there is a problem about the of Being," he, Meaning the "question of for themoment, will not. Why not? Because, says Ryle, the relation between Being qua timeless 'substance' and existing qua existing in the world of time and space seems tome a real one."1 Other analytical philosophers, however, have been decidedly question "What is the meaning of Being?". In a celebrated review of

readily be called a "doctrine" of existence, it is one which seems to outlaw most of what we seem to find said about Being in thewritings of philoso phers like Heidegger.3 Hence, for example, Paul Edwards, basing himself on arguments of Russell, roundly declares that "Heidegger's problematic

for instance, Bertrand Russell declares that "an Logic and Knowledge, amount of false philosophy has arisen through not almost unbelievable 'existence' means." And, though Russell has what can realizing what

unhappywith talkabout Being of the sortassociatedwithHeidegger.2 In

We may wonder, for instance, how cogent it is as itoccurs in the writings

of Thomas

is a pseudo-inquiry and his quest is a non-starter."4 I am no expert on Heidegger, and Edwards may well be right inwhat he says of him. But "Being-talk" is something to be found in authors other than Heidegger, and we may wonder about its cogency as they develop it. Aquinas, where "Being-talk" abounds. According toAquinas,

God is "subsistentbeing" (ipsum esse subsistens) and the cause of the most ap being (esse) of creatures. Having asked whetherQui Est is the name forGod, Aquinas replies that it is since, among other propriate

reasons, "it does not signify any particular form, but rather existence itself the existence of God "Since is his essence," (sed ipsum esse)" says "and since this is true of nothing else ... it is clear that this name Aquinas, is especially appropriate toGod."5 Aquinas's whole philosophical and the

"Aquinas, God, and Being" by Brian Davies, O.P., The Monist, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 500-520. Copyright ? 1997, THE MONIST, La Salle, Illinois 61301.

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

501

But is theteaching any of ological outlook is dominatedby thisteaching.

importance or value?

Writers in theThomist tradition have, unsurprisingly, praised it in

terms. According, for instance, to Fr. Norris Clarke, S.J., "The

makes

crown of theentire Thomistic vision of theuniverse is thenotion ofGod as infinitely Source andGoal purePlenitudeofExistence,ultimate perfect of all otherbeing."6According to Etienne Gilson, thenotion towhich of Clarke refersconstitutesthe truegenius and originality Aquinas and of work of Yet thisendorsement Aquinas is notmuch echoed in the in the analytic tradition. the contrary. the In Quite philosopherswriting

Kenny, for instance, Aquinas's teaching about God as esse subsistens can be described as "sophistry and illusion."8 In the ipsum it is "entirely empty of content."9 According to view of Anthony O'Hear, view of Anthony him a genuine existentialist.7

glowing

undermined C. J.F. Williams, it is thoroughly by thework of Gottlob

to Terence Penelhum, it is evidence for the fact that, Frege.10 According saw that there is something wrong with the so-called "On though Aquinas tological Argument" forGod's existence, he did not see why theArgument fails. Aquinas holds that though God's existence is not "self-evident to us" essence and (per se notwn quoad nos) it is evident in itself since God's existence are identical. This conclusion, says Penelhum, is philosophical ly suspect. "The distinctive character of the concept of existence," he

explains, "precludes our saying that there can be a being whose existence follows from his essence; and also precludes the even stronger logical move of identifying the existence of anything with its essence.... To say

but the logical character of the concept of existence."11 start by defending the foes. For, in one way

that although God's existence is self-evident in itself it is not to us, is to say that it is self-evident in itself, and the error lies here. It is not our ignorance that is the obstacle to explaining God's existence by his nature,

to and foes ofAquinas we can In trying adjudicate between friends

or other, these are often

Kantian"

notion of being, and worries about such a notion are legitimate is obviously not a real and well founded.12 Kant insisted that "'Being' a on the face of it, a predicate."13 The thesis is famous one, but it is not, predicate or not before we know what the question means. Yet regardless

opposed toAquinas since theyfind in himwhat we might call a "pre

clear one. It is impossible to answer thequestionwhetherexistence is a

502

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

predicate is to say that,while there are predicates which do give us infor is not one of them. If "Brian mation about Brian Davies "_exist(s)" snores" is true, someone who comes to know this learns something Davies about Brian Davies. Davies. Or "Brian Davies This, however, so I want to suggest. But manner. snores" says something about Brian not the case with "Brian Davies exists." is let us consider the question

Brian Davies is an object or individual;and to say thatexistence is not a

serve to tell us anything about any object or individual. By "object" or "in I mean dividual" something that can be named. On my account, then,

of anything Kant says, the thesis that existence is not a predicate can, I think, be given a clear meaning on the basis of which we can treat it as can never correct. Quite simply, we can take it tomean that "_exist(s)"

in a thor

My thesis is that it is right to say that"Brian Davies exists" says nothingof Brian Davies, indefense ofwhich I offertheobservationsof might be raised in response to this thesis, objections which can be

expressed as follows.14 (1) First, we learn something about somebody or something when we I learn that Fred Smith or Jane learn that he, she, or it exists. Suppose the last paragraph but one. On the other hand, however (sed contra), there are objections which

oughly Thomistic

exists. I have surely learned something about them. Suppose I Bloggs discover that Montmartre exists. I have surely learned something about it. (2) Second, not knowing that someone or something exists is being II does not ignorant of a truth concerning that person. Queen Elizabeth know that Brian Davies exists. And here she is ignorant of a fact about My mother does not know sentences that the pen on my desk exists. exists" seem tomake

Brian Davies.

of And here she is ignorant a factabout it.

(3) Third, like "Brian Davies

sense.

The subject is Brian Davies. So it looks as though "exists" tells us

something about him.

thiswe can use theword

To (4) Fourth, some thingsare real as opposed tofictional. indicate

'exist'. Thus: "President Clinton exists but David

Copperfielddoes not exist." It follows thatthereis somethingthatis true of of PresidentClintonwhich is not true David Copperfield. Next he replies to commonly thenargues ina positiveway for the thesis.

Having raised objections to a thesis he wants to defend, Aquinas

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

503

three argu by beginwith, I shall tryto saywhymy thesis is true offering

ments.

the objections. At this point, therefore, I shall follow that practice. And,

to

do not exist" are false of necessity, like "Fun-loving Welshmen exist" are true of necessity. and (b) assertions like "Fun-loving Welshmen serves to tell us something significant if "_exist(s)" Why? Because assertions about some object or individual, then denying that "_exist(s)"

simplyby acceptingwhat I say. For ifmy thesis is false and if "_ about an object or individual,then(a) exist(s)" serves to tellus something

First, denial

of my

thesis leads to a paradox which

can be avoided

nificant (expressed by "_exists") individual. But of what non-existent

of affirmable some object or individualisdenyingthatthissomething sig

is truly affirmed of some object object or individual can "_does

is truly or

The not exist" be sayinganythingsignificant? whole point of assertions tell us somethingabout some object or individual,it looks as though

of existence must always be false. Yet that thesis surely cannot be can it be true that affirmations of existence are always true? do not exist" is to deny that there are any fun like "Fun-loving Welshmen can serve to So, on the assumption that "_exist(s)" loving Welshmen.

denials

true. Nor

though this thesis also seems to follow from the suggestion that "_ exist(s)" serves to tell us something about an object or individual. For if, on this assumption, denials of existence are always false, itwould seem that affirmations of existence are always true. in by "some" are fun-loving." Nobody, sentences like "Some Welshmen I presume, would take "some" to ascribe any kind of property or characteristic to any object or individual. But if in such cases the work done by "_exist(s)" that done is the same work To the work done by "_exist(s)" Second, exist" is the same work Welshmen loving in sentences like "Fun as

so to function as to ascribe anykind of property any object or individual.

see the force of this argument, consider Welshmen

as that done by "some,"

then "_exist(s)"

does

not

Welshmen personallyknown to us are as may be true thoughall the

anything but fun-loving. Would you feel forced to conclude that there are no fun-loving Welshmen? not. "Fun-loving Welshmen exist" Obviously

Welshmen. But suppose Ianto andDewi and Idris?all of them fun-loving come tobe thoroughly thatIantoandDewi and Idris suddenly gloomy and

exist." You may agree that this assertion

the assertion "Fun-loving is true since you know

504

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

man.

exist" gloomy as can be. In that case, however, "Fun-loving Welshmen cannot be construed as telling us something about any particular Welsh are fun-loving." Nothing It is, in fact, equivalent to "Some Welshmen exist" by "Some Welshmen is lost by rendering "Fun-loving Welshmen are fun loving." Now focus on sentences the meaning like "Some Welshmen containing of sentences

derstanding

are fun-loving." Un words like 'some' is

are we doing as we might say "Margaret is a smoker." What this assertion? We begin with a name: produce 'Margaret'. Then, in the of A. N. Prior, we try to "wrap it up" in the expression happy expression We '_is a smoker'.15 The expression '_is a smoker' is in an obvious

To achieved by grasping theirlogical structure. do thisit ishelpful to look we build up toa propositionof thistype. at thestagesbywhich, as it were,

around

'Margaret' around which that wrapping wraps. And, note, the conjunction of these wrappings creates the equivalent of not smoke," which we can wrap round another wrapping?"_does 'Margaret' assertion

is a smoker." How? negate "Margaret By using a new "It is not the case that_" and wrapping it around "Margaret wrapping a is a smoker." This new wrapping wraps around the wrapping "_is We smoker" and the name

'Margaret', ending up with a complete "Margaret is a smoker." can

sense incomplete.It is like a piece of wrapping paper waiting to have And we make something put inside it. something completebywrapping it

and intelligible expression:

Is it like thiswith "Fun-loving Welshmen exist?" I say that this

is equivalent to "Some Welshmen are fun-loving." But what are

to say "Margaret

does not smoke."

same process as that which left us arriving at "Margaret is a smoker?" If we were, we should be wrapping "_are fun-loving" around "Some But if that is how we get to "Fun-loving Welshmen Welshmen." exist" of "Margaret is a smoker," i.e., by wrapping "It is not the case around "_are And this fun-loving" and "Some Welshmen." "a new wrapping: are non-fun-loving should produce wrapping are non-fun-loving" But it does not. "Some Welshmen Welshmen." is not negation that_"

we doing as we build up to thisassertion? Could we be going through the

we then ought toget to thenegationof thisassertionjust as we got to the

compatiblewith each other. Nothing in logic tellsus thattherecannotbe

fun-loving Welshmen as well as non-fun-loving Welshmen.

the negation

of "Some Welshmen

are fun-loving."

These

assertions

are

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

505

Let us therefore try another approach. To be precise, let us entertain are fun-loving" it is "Some the thought that in "Some Welshmen that wraps around "are fun-loving." The thought proves illu Welshmen" are For now we can properly negate "Some Welshmen minating. This last ex fun-loving" by prefixing itwith "It is not the case that_." are fun-loving" in the same will wrap around "Some Welshmen pression way that "It is not the case that_" wraps around "Margaret is a smoker" to produce

dividual.16

exist" is the same work as that done by 'some' in "Fun-loving Welshmen are fun-loving." And, if that is true, "_ sentences like "Some Welshmen does not serve to ascribe any kind of property to any object or in exist(s)"

a new wrapping: "no Welshmen_" are (as in "No Welshmen to "Fun-loving Welshmen do not exist"). Or, to fun-loving"?equivalent in sentences like repeat what I said above: thework done by "_exist(s)"

objects. Frege argues that statements of number do not ascribe properties to objects. If he is right, then statements of existence (e.g., "Fun-loving Welshmen exist") do not ascribe properties to objects. propositions

where he is rejecting the suggestion thatnumbers are properties of

from comments Frege makes

The third argumentI offer in defence ofmy thesis is one derived

in The Foundations of Arithmetic at a point

like "The King's carriage is drawn by four horses" and "The King's carriage is drawn by thoroughbred horses." Going by surface ap one might that 'four' qualifies 'horses' as does pearances, suppose 'thoroughbred'. King's

To begin with, Frege draws attentionto the differencebetween

King's about any individual

But that, of course, is false. Each horse which draws the carriage may be thoroughbred, but each is not four. "Four" in "The carriage is drawn by four horses" cannot be telling us anything horse. It is telling us how many horses draw the

carriage. So, Frege argues, statements of number are primarily answers to questions of the form "How many A's are there?"; and when we make them we do not assert something of an object (e.g., some particular horse). He reinforces his point by the example "Venus has 0 moons." statements are statements about objects, about which object(s) none. If I say "Venus or agglomeration If number is "Venus

has 0 moons?"

Presumably, "simply does not exist any moon

numbers

to be asserted of." That is, if 'one' is a propertyof an object, and if

greater than one are properties of groups of objects, 'nought'

has 0 moons," there moons for anything of

506

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

must be ascribable non-existent Now, object

to non-existent is not to ascribe

Affirmationof existence is in fact nothingbut denial of the number

nought."17 And ifFrege is right about number, that is correct. Indeed, we can strengthen the claim. For statements of existence are more than

says Frege,

"In this respect, existence

objects. But to ascribe it to anything.

a property to a to number.

is analogous

questions are no less answers for being relatively vague. Nor do they fail to be answers because they are negative. In answering the question "How I many A's are there?" I need not produce one of the Natural Numbers. may just say "A lot," which is tantamount to saying "The number of A's is not small," or "A few," which is tantamount to saying "The number of A's is not large." If I say "There are some A's," this is tantamount to saying "The number of A's

to statements of number; they are statements of number. As analogous C. J. F. Williams puts it, "Statements of number are possible answers to of the form "How many As are there?" And answers to such questions

is not 0." Instead of saying "There are a lot of A's" I are numerous," and instead of saying "There are some A's" may say "A's I may these may be regarded as statements of say "A's exist." All

number."18

of existence, then, are statements of number. They are to the question "How many?", and, considered as such, they do not ascribe properties to objects. From "Welshmen are fun-loving" and Statements answers "Welshmen are numerous" and "Idris is a Welshman" I cannot conclude

"Idris is a Welshman" I can infer that Idris is fun-loving;but from

that Idris is numerous. "Idris is numerous" means nothing. From "Readers is a reader of The Monist" I can

of The Monist

is not nought" ("Fun-loving Welshmen number of fun-loving Welshmen I ought not to conclude that and "Idris is a fun-loving Welshman" exist") Mary could be scarce.

are literate" and "Mary is literate; but from "Readers of The Monist are scarce" infer thatMary I cannot conclude and "Mary is a reader of The Monist" thatMary is scarce. "Mary is scarce" means nothing. By the same token, from "The

Idrisexists.That would be like saying thatIdriscould be numerousor that

So I continue to suggest that "_exist(s)" can never serve to tell us

manner

But what of theobjections to this thesis anythingabout any individual. noted above? If my thesis can be defended, can objections to it be answered? I thinktheycan, and I shall attemptto reply to them in the

of Aquinas.

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

507

such sentences. We might make sense of them by taking the occurrences in them as intended to convey what may be asserted by of "_exist(s)" means of expressions like "_is alive" or "_is still a region of Paris" ; say that they are alive, just as we succeed in saying something about when we say that it is still a region of Paris. By itself, Montmartre does not serve to tell us anything about any object however, "_exist(s)" or individual. we

Reply to obj. 1: By themselves, sentences like "Fred Smith exists" or "Jane Bloggs exists" do not ascribe properties to any individual. The same goes for sentences like "Montmartre exists." Normally we have no use for

we aboutFred or Jane and it is truethat succeed in sayingsomething when

property. In context, however, we might make sense of someone who II does not know that Brian Davies says, for example, "Queen Elizabeth exists." Among other things, Brian Davies (the present author) is the

since "_exist(s)" does not serve to tell us anything about any object or individual, they cannot be viewed as expressing someone's ignorance to the effect that some object or individual has a particular

sense. And

like "Queen Elizabeth II does not know that Brian Davies exists"make

Reply

to obj. 2: It is by no means

clear that, by themselves,

sentences

II does not know that someone wrote The things as "Queen Elizabeth and that the same person was born in Thought of Thomas Aquinas London, is the son of Lillian like "Brian Davies

nothing about what can be truly affirmed of him. We might try to convey this by saying that she does not know that Brian Davies exists. But we shall only be able successfully to convey what the Queen's ignorance amounts to by disposing of the expression "_exists" and saying such

authorof a book called The Thoughtof ThomasAquinas. Let us suppose that Queen Elizabeth II knows nothingof such an author and knows

sense, on the assumption that is supposed to tell us something about "_exists" Brian Davies. Let us say that a 'first-level predicate' is a linguistic ex pression such as "_is fun-loving" which serves to tell us something sentences exists" make in such sentences that it is true that Fred is fun-loving, so "_is learn nothing comparable "_exist(s)" fun-loving" is a first-level when learning that Fred

Reply to obj. 3: Given the argumentsabove, we may deny that

and Brian Davies,

is a philosopher,

etc."

we learn about a specificindividual. of Hence, we learnsomething Fred if

predicate. But we exists, for reasons given above. predicate.

cannot serve as a first-level

508

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

David Copperfielddoes not exist and Reply toobj. 4: Asserting that true President PresidentClinton does, isnot tohold thatsomething of that Clinton is not trueof David Copperfield (as beingAmerican is trueof Hilary Clinton but not ofMargaret Thatcher). IfDavid Copperfielddoes

not exist (if there is and never was

have any properties. As Peter Geach observes, writing about the assertion "Cerberus doesn't exist" (i.e., is not real, like Rover): "We are not lacks; for itwould be pointing out any trait that Rover has and Cerberus nonsense more to speak of the trait of being what there is such a thing as, and nonsense to say that some things (e.g., Rover) have this trait,while

a property possessed byHilary Clinton.He isnot (and neverwas) thereto

any such person)

then he does not lack

other things(e.g., Cerberus) lack it,and are thus thingsthatthereis no

such thing as."19 As Geach says: "logically our proposition is about a dif ference not between two dogs, Cerberus and Rover, but between the uses 'Cerberus' and 'Rover'. The word 'Rover' is seriously used of two words to refer to something and does term that we only make believe

in fact so refer; the word 'Cerberus' is a has reference."20 To say thatDavid Cop names does not exist, then, is to deny that "David Copperfield" perfield When we make assertions about David Copperfield anything.21 (e.g., that he is kind-hearted) we pretend to use "David Copperfield" as a genuine

name.

language of Kant, "being" is not a real predicate. But must we therefore this says about God as ipsum esse subsistensl Does reject what Aquinas teaching offend against anything I have been arguing above? God is ipsum esse subsistens since God's essence is esse. Also according toAquinas, God brings it about that creatures have esse, considered as an is the present infinitive of the verb 'to be'. But, as Aquinas

So we may happily take sideswith those who want to say that,in the

One can see why it For Aquinas, might be thoughtto do just that.

word

effect broughtabout by God. How shallwe renderesse here?The Latin

often

were a kind of noun.And thatis how as uses it, it is best translated if it

often render it.As Aquinas often uses the word, it translators of Aquinas can literally be rendered as 'the to be'. Normally, though, when Aquinas uses esse in this sense, translators report him as talking about 'being,'

which is a perfectlyrespectable him. So the teaching way of translating that God's essence is esse might be said to amount to theclaim that God we ask whatGod is theanswer is simply"Being." By is being and thatif

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

509

might be said to amount to the claim thatGod brings it about that

creatures exist, on the understanding that it is a fact about creatures that they exist (as, for example, it is a fact about some creatures that they are then he is indeed guilty of supposing essence is esse would amount that "_exist(s)" can serve

the same token, the doctrine

thatGod

brings about

the esse of creatures

and that God brings about thisfact. If this is how we read fun-loving), to tellus somethingsignificant an object or individual. of The teaching

to the claim that just as Ianto,

Aquinas

that God's thatGod

God is being (or existence).The teaching Dewi and Idris are fun-loving,

is the cause of the esse of creatures would (being, existing) amount to the claim

brought about by God. And if this is what Aquinas thinks,thenhis is of thinking decidedly suspect.Self existing is not a property any indi thattheanswer to "What isGod?" is "God how can itbe thought vidual,

is existence?". As we have something is thus and number nought. But it hardly makes (where "anything" =

that there is a property

had by creatures?a

property

seen, affirmations of existence tell us that so. They can also be viewed as denials of the sense to reply to the question "What

as isGod?" by saying "God iswhat somethingis insofar it is anything"

"anything affirmable of some individual"): Nor does

be a truth about any object or individualthatitexistsand that God brought

this about. God, But he cannot bring it about that something exists anymore than he can bring it about thatMary (or Ianto, Dewi, or Idris) is scarce or numerous.

saying that the number of gods is not nought.22 And if "_exist(s)" cannot serve to tell us something about any object or individual, it cannot one might say, can bring it about that something is a dog

make much sense to say that "What isGod?" is intelligibly it answeredby

U.S.A. (Jane (Fido), or red (British Mansfield). post boxes), or born in the we more deeply into At thispoint,however, need todig a little what

says about God as ipsum esse subsistens and about God as the Aquinas source of the esse of creatures. For his teaching on these matters is not to

when he writes of sentences containing

To be disposed of along the linesof the lastparagraph. begin to see why whichAquinas says this is so,we can start noting some of the things by

forms of the verb

ways. As he himself puts it: "there are two proper uses of the term 'being' :

ically, according to Aquinas, theverb 'tobe' isused inat least twodistinct

'to be'. Specif

whatever falls intoone ofAristotle's tenbasic cate firstly, generallyfor

gories of thing, and secondly, for whatever makes a proposition

true.

510

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

These

differ: in the second sense anything we can express in an affirma tive proposition, however unreal, is said to be: in this sense lacks and absences are, since we say that absences are opposed to presences, and an eye. But in the first sense only what is real is, so that blindness exists in in this sense blindness

as thoughtheyare doing this,though,in fact theyare not. If I say that Paul II ispious, I am telling about a distinctin you something Pope John use Aquinas's example), I am not doing this ifI say that dividual. But (to

blindness exists. There But "blindness" Aquinas wants are, of course, people and animals who cannot see. is not the name of any individual thing. And that is what

something about a distinct individual, and sentences which

What does Aquinas have in mind in To making thisdistinction? put is distinguishingbetween sentenceswhich tell us things loosely, he

look or sound

and such are not beings."23

in "Blindness exists," which which can be called "blindness" something animals cannot see). vidual (as What is it thatAquinas

to say. On his account, existence statements can tell us something about an individual (e.g., "Pope John Paul II is pious"), or they can tell us something true without telling us something about any indi is true not because but because some people and

there is

takes existence

he says that 'being' can be understood with respect to what falls under ten categories, he does not mean that something can be said to Aristotle's be

One thinghe does not take they tellus somethingabout an individual? us themtobe doing is telling thatthesomethinginquestion exists. When

statements to be doing when

between things and itdoes not tellus anything about help us todistinguish

anything. For, on Aquinas's But, for Aquinas,

'existing' and that 'existing' can serve to tell us anything significant one way of distinguishing between individuals is in about it.For Aquinas, terms of genus and species. So we can say, for instance, that Fido is a dog cannot serve to and that Sara is a woman. Yet 'is a being', for Aquinas, account, it does not signify a way of being

woman.

(what something is). JohnPaul II is a man. And Hilary Clinton is a

there is nothing which can be characterized

is not a generic term. It cannot serve to tell us what something is.24On his account, genuine individuals are whatever they are by virtue of what he

simplyby saying thatit is.FollowingAristotle, Aquinas agrees thatthere as isno suchclass of things things which simplyare. 'Being', for Aquinas,

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

511

calls

'form'. And

it is with

this notion

in mind

Aristotle's

that he appeals

to

Thor. Thor

try to tell you about is enormously He is intelligent. He is large. younger than his parents. He lives inNew York. He is alive as I write. He sits down when he eats. He is very hairy. He chases lots of mice. And he is a cat. He is castrated.

Categories. I have a friend who has a cat called Thor. Let me

Following Aristotle,Aquinas would say that I have just told you Categories,Aristotle triesto classify quite a bit aboutwhat Thor is. In the

ways inwhich we may speak of things.We may say what something is es sentially (e.g., "is a cat"), or how big it is, or what it is like, or where it is, or what it is doing, and so on. And Aquinas agrees with this kind of clas sification. For him they are ways of saying what something is. And he a cat," "_is that when we say what something is (e.g., "_is is intelligent"), we are ascribing a form to enormously large," "_ something. Forms, for Aquinas, are nothing like the subsistent entities

holds

feline and being intelligent are factors thatmake up the being of Thor, so say. If we ask what it is for Thor to be Thor, then, so Aquinas would Aquinas would say, it is for Thor to be feline, intelligent, and whatever

it aboutThor. Being Thor; in "Thor is intelligent" also tellsus something

For themost part, a form, forAquinas, is what is signified by a predicate us something about an individual. Thus, for example, expression telling a cat' signifies a form: in "Thor is a cat" it tells us something about '_is

can be subsistent he forms. postulatedby Plato, though thinksthatthere

else can be intelligibly and truly affirmed of him. On Aquinas's account, the existence of Thor is reportable by saying what Thor is. "No entity without identity," says W. V. Quine. Or, as Aquinas puts it, existence is of given by form (forma est essendi principium).25 "Every mode "is determined by some form" (quodlibet esse existence," says Aquinas, est secundum formam).26 For Aquinas, we cannot describe something by exist is to be or to have form. Hence,

as and saying that, well as being feline,intelligent so on, italso exists.To

sense of statements like 'Thor exists'

they tell us what something is. Thor est, said of Thor the cat, means, for "Thor is a cat." Or, to change the example, according toAquinas Aquinas, names like 'Socrates' or 'Plato' signify human nature as ascribable to

for instance, Aquinas can only make (Thor est) on the understanding that

512

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

certain

individuals. Hoc secundum

nomen

humanam

quod est or Plato saying Socrates existence had by Socrates and Plato. are by nature, i.e., human.

est in hac mataer?aP

'Plato* significai naturam On Aquinas's account, est is not to inform people of a property of 'Socrates' vel It is to assert what Socrates and Plato

In short, alert to thedangersof saying that"_ Aquinas is perfectly can serve to tellus anything What about any object or individual. exist(s)" we have just seen him saying shows that could happily agreewith the he

case I made above for existence

we should indeed be Dewi, Idris and the like.And that suggests that

cautious

not being a property ascribable

to Ianto,

taining that there is a property (being, existing) had by creatures?a property broughtaboutbyGod, who in some mysterious sense just IS this

property. In that case, however, what does Aquinas mean when he speaks of God as cause of the esse of creatures and of God as ipsum esse subsistensl is derived from what we know of creatures. There is no direct human

in supposing that in speaking of God as ipsum esse subsistens, and in speaking of creatures as owing their esse toGod, Aquinas ismain

A fundamental of anyknowledgewe have ofGod teaching Aquinas is that withinour ex knowledge ofGod akin toour knowledge of objects falling

as we might call by acquaintance," perience ("knowledge account too, human knowledge of God cannot be something on the concept of God," as we might call it).28 According in this respect is remarkably empiricist: "The knowledge sensible

it). On his inferred on

of thebasis of some priorunderstanding what God is ("knowledgebased

toAquinas, who that is natural to

us has its source in the senses and extends just so faras itcan be led by

things; from these, however, our understanding cannot reach to the present life our intellect has a natural relation the divine essence_In ... In this sense cannot, of knowing thatwe experience, un since they are not subject to the senses and it is obvious that we

turning to sense images. primarily and essentially, derstand whatness God

to thenatures ofmaterial things; thus itunderstandsnothingexcept by

in themode

. imagination. . . What is understoodfirst us in thepresent life is the by

of material by way . . . [hence] ... we arrive at a of things knowledge of creatures."29 As Herbert McCabe, O.P., nicely puts it,

immaterial substances

we Aquinas's view is that"whenwe speak ofGod, although know how to

use our words, theymean. derstanding there is an important sense inwhich we do not know what . . We know how to talk about God, not because of . any un of God, but because of what we know about his creatures."30

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

513

On Aquinas's account, there are philosophical puzzles which arise with to theworld of our experience. And these puzzles are our basis for respect on esse as had by creatures, talking of God.31 So to understand Aquinas to understand what he means in speaking of God as ipsum esse sub and sistens, we shall need to startby looking a bit more at what Aquinas to note the point we need most especially of creatures. And creatures, forAquinas, assume are more than themeanings of words. are enchanted thinks is that

aboutFred thehappyunicorn. We shall Suppose I am tellinga story

I am telling the story to a group of children who

with Fred the happy unicorn from theirbook reading and television mind an interesting With this scenario in viewing. thingto note is thatI

can be wrong in what I say about Fred. Suppose I observe that Fred has no horn on his forehead. Any sensible child will rightly correct me. "But Fred is a unicorn and unicorns have horns on their foreheads," the child

will The

need tobe careful toget things my taleofFred. rightas I tell

On have horns will might say, a mythical

say. And rightly so. Of course unicorns have horns on their foreheads. fact can be quickly verified. Just consult a decent dictionary. So I the other hand, however, dictionaries which confirm that unicorns also tell us that unicorns are mythical animals. So we

animal does not exist. But in that case how can I be since I can offend against what people can of certain words. The word 'unicorn', for

of The answer,of my story Fred thehappyunicorn? wrong when telling

is that I can be wrong take to be themeaning rightly course,

mistakes

can entertain people with stories about unicorns. One can even make about unicorns, albeit that unicorns do not exist. Now suppose we ask what a unicorn is. Our answer will have to be shall start, perhaps, with a based on some literary detective work. We to other writings in which then move standard dictionary; 'unicorn' occurs. And, ifwe are very persistent, we shall, from our reading, have lots to say about unicorns. Yet there never have been any unicorns. That

instance,is not a piece of gibberish.It is therein thedictionariesand one

word 'unicorn'. what peoplemean by the We are seeking seekingto learn a kind of nominal definition. Knowing what a unicorn is simplyamounts

themeaning of a word. is perfectly aware of this fact. He Aquinas reason for rejecting a famous argument for God's to knowing of the word even appeals to it as a existence based on the

iswhy I say that our answer to the question "What is a unicorn?" will have to be settled on literary grounds. In trying to answer the question, we are

meaning

'God'.32 For him, however, we might know what

514

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

what a dictionarytellsus goes beyond learning somethingis ina way that

that a word

what

of and in this way be able to say understanding things develop a scientific

they are. There are no unicorns. But there are lots of cats. And

(e.g.,

'unicorn') means.

For, in his opinion, we might actually

can certainly get our hands on Thor and his fellow cats. And (as has on this basis we can develop an understanding of cats. As happened), Aquinas would say, we can begin to explain what it is to be a cat. Or, as

never be able to study Fred (or any of his fellow mythical unicorns),we

though we

shall

we might put it,we can begin to explain what cats actually are?some thing we cannot do with respect to unicorns and the like since they are not actually anything. For Aquinas, then, there is a difference between "A unicorn has a horn on its forehead" and anything that a scientist might come up with as an account in mind when have of what cats are. It is this difference which Aquinas he says that creatures have esse. Translators has chiefly of Aquinas

rendered him as saying that creatures have being. And we need not quarrel with the translators. The expression habere esse recurs inAquinas,

easily suggest that 'being', for is a property which something has?as, for example, redness is Aquinas, a property of most British post boxes. And that is not at all what he thinks. His idea is that in truly knowing what, for example, a cat (as opposed to a unicorn) is,we are latching onto the fact that cats have esse. And the best footnotes). "It is not simply in our capacity to use signs, that, according toAquinas: our ability for example, to understand words, but in our actual use of them things."33 Given

and I do not know how to translate it except by writing 'to have being' (or 'to have to be' which is clumsy and unintelligible without a lot of learned But such a translation could

McCabe usefullyputs it, way of expressing thisfact is to say,as Herbert we to saywhat is thecase that have need of and layhold on theesse of

what I have been saying, Aquinas's teaching on esse is

For him,we layhold on the decidedlymatterof factand even pedestrian. esse of things living in the are. world and by truly what things by saying We layhold on theesse ofThor, forexample, by notingthat Thor is a cat

which. lay hold on esse by being natural scientists exploring our and talking about it as we try to understand it.34 InAquinas's view, however, our environment itself is a puzzling thing. For how come environment . . We .

theworld in which we try to say what thingsare? At the end of his TractatusLogico Philosophicus LudwigWittgenstein says: "not how the

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

515

world when even

is, is themystical, but that it is."35 For Wittgenstein, how theworld a scientific matter with scientific answers. But, so he insists, even is is the scientific answers are in,we are still leftwith the thatness of the

world, the fact that it is.As Wittgensteinhimselfputs it; "We feel that world and develop an account ofwhat thingsin it he thinks, explore the

are. But we if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life is of the same mind. We can, have still not been touched at all."36 Aquinas are still left with a decidedly non-scientific question. How

come thatthe will be clear world is? Fromwhat I have writtenabove, it

takes the world to do. For that "ising" is not something that Aquinas there is nothing that ises.37 There are cats and dogs and readers Aquinas, of The Monist. There are all sorts of things to be explored and reported on even the sharpest ear will not tune into by scientists. But, for Aquinas, something ising.38 Yet is one which Aquinas to ask "How

come things having esseV, and he thinks of the as causal. Or, as we may also put it,Aquinas's view is that, as question well as asking "What in the world accounts for this, that, or the other?", we can also ask "Why any world at all?". How come the whole familiar natural business

the fact thatwe can think of things as having esse finds important and suggestive. For he finds it

of asking and answering "how come?". And it is here that terms of God. For him, the question "How come any thinks in Aquinas is a serious one towhich theremust be an answer. And he gives universe?" towhatever the answer is. God, forAquinas, is the reason there is any universe at all. God, he says, is the source of the esse of why fact that they are more than themeaning of words. Consid things?the ered as such, Aquinas adds, God is ipsum esse subsistens. the name "God"

us God is an is-ing We God generically.It is not telling that kind of thing.

have seen enough to warn us away from that sort of interpretation, as well

Now, however, we need to ask what work this teaching is doing in the body of Aquinas's writings. It is evidently not attempting to locate

as fromanywhich would take God Aquinas tobe identifying with being to or existencewhere thatis thought be a property objects or individu of

als.39 In that case, however, what does Aquinas is ipsum esse subsistens Aquinas answer needs a little unpacking. thatGod means mean when holding that the

answer is thatin saying that God God is ipsumesse subsistens!The short

thatGod is not created. But

doctrine

his To start withwe shouldnote howAquinas himselfcharacterises

is ipsum esse subsistens. Since the expression seems to

us be telling what God is,onemight expect Aquinas to speak of itas part

516

BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

of an account does. We

subsistens comes in. It is part of an account of ways in which God does not exist. To be more precise, it is part of an attempt to note ways inwhich God is, as Aquinas puts it, non-composite. is something that creatures can be said Being composite, forAquinas, to be. And

with considering"theways inwhich God does not exist, ratherthan the And it ishere that talkofGod as ipsumesse his which he does."40 ways in

properties or attributes. But that is not what he We must content ourselves cannot, he argues, know what God is. of God's

there are, so he thinks, various ways inwhich creatures can be to be composite.41 With our present concerns in view, however, a thought a matter of being point to grasp is that being created is, for Aquinas, are what they are not just because for Aquinas, composite. Creatures,

other creatures have brought it about that they have begun to be and not just because other creatures play a role in keeping them going. According toAquinas,

creatures are dependent in a deeper sense, which he puts by saying that their esse is derived. They are dependent in the sense thatwe can ask "How come any world at all?". Wittgenstein found it striking that

left, and just this is the questions, he says, "there is then no question a part of the world. And answer."42 We cannot speak about what is not at one level, agrees?hence his assertion that we cannot know Aquinas, what God is. He knowledge in our universe nowadays call of God does not intend to suggest that we can claim no at all. He does, however, think thatGod is not an object with respect to which we can have what we would understanding." According to Aquinas, we

theworld is. And this lead him to silence. Having asked scientific

a "scientific

material

More precisely, we know what something is world and define it. we can locate it in terms of genus and species.43 So Aquinas when denies

knowwhat somethingis (quid est)when we can single itout as partof the that God belongs to a natural class and that God can be definedon this basis. Yet Aquinas does not at thispoint lapse intosilence.One thing he can speak truly noting we what could notpossibly be true holds is that by of whatever it is thataccounts for things having esse. And since things

having esse are derived, itmakes sense, he thinks, to deny that whatever accounts for things having esse is, in the same way, derived. Or, as puts it, in God there can be no composition of esse and essence Aquinas creatures exist by being God is ipsum esse subsistens). For Aquinas, (i.e., what they essentially are. Hence, for example, for Thor to be is for Thor

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

517

to be

a cat. But

how

come

accounts

must be "outside

God with someparticular way ofbeing.As he puts it,ifthereis a God then

the realm of existents, as that exists in all its variant every thing existens, velut causa quaedam profundens entias).44 And this is the heart ofAquinas's subsistens. That forms" totum ens et omnes eius differ teaching thatGod is ipsum esse

for that, so Aquinas

that anything has an essence? Whatever thinks, cannot be something in the world

a cause from which pours forth (extra ordinem entium

teaching is not an attempt to tell us what God is. It is an to tell us that, whatever else we might want to say of God, we attempt must bear in mind that God is not created. Its content is exceedingly "doctrine" of God negative (as, so I have argued elsewhere, isAquinas's in general).45 "Our minds," Aquinas observes, "cannot grasp what God

is

him as he really is."46 And Aquinas takes this teaching to apply just as much to the assertion thatGod is ipsum esse subsistens as it does to other things we say of God. to understand Yet is it true that God expound Aquinas's teaching is ipsum esse subsistens! I have tried to so as to indicate that, if nothing else, it is

of inhimself;whateverway we have of thinking him is a way of failing

modern claim

of something which a modern philosopher mightwell takeaccount since itaccordswithwhat a modern philosopher mightwell want to say on the of existence. I am temptedto say thatit is something which a of topic

analytical philosopher might take account; but I cannot really or not we to know what makes a philosopher analytic. Whether

depend a lot on whether we can share his puzzle concerning the fact that we can talk of the world and make sense of it in its own terms (that we can be scientists). It will also depend on whether we find the word 'God' an appropriate one to use when

God is ipsumesse subsistens will agreewithAquinas inhis teachingthat

occasion.

to to that trying move on. I think Aquinas is right be puzzled as he is.And I findhim tomake a very good case for invokingthe word 'God' when But that ismatter for another seeking to talk about the esse of things.

seeking

to express

such puzzlement

and

Brian Davies, Fordham

O.P.

New York

University,

518 BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

NOTES

1. Gilbert Ryle, Collected Papers, vol. I (New York: Barnes andNoble, 1971), p. 211. 2. I employ the expression "analytical philosopher" in accordance with the usage suggested by the article on analytic philosophy in Ted Honderich (ed.), The Oxford Companion toPhilosophy (New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1995). 3. BertrandRussell, Logic and Knowledge (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1966), p. 234 and pp. 228-34. 4. Paul Edwards, "Heidegger's Quest forBeing," Philosophy 64 (1989), p. 459.

5. Summa 6. Norris

Notre Dame Press, 1995), p. 24. 7. Cf. Etienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (London: Victor Gollancz, 1961), Introduction and chs. Ill and IV. Gilson on Aquinas is heavily Existence and Analogy (London:Darton, Longman andTodd, endorsedbyE. L. Mascall in 1949). 8. AnthonyKenny,Aquinas (Oxford:Oxford UniversityPress, 1980), p. 60. 9. AnthonyO'Hear, Experience, Explanation and Faith (London; Routledge, 1984),

p. 64. 10. C.

la, 13, 11. Theologiae, S.J., Explorations Clarke,

inMetaphysics

(Notre Dame,

IN: University

of

Mitchell's

Companion toPhilosophy ofReligion (Oxford:Blackwell, 1997). InWhat isExistence? and Truth (Oxford; (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), and in Being, Identity, Williams develops a critiqueof Thomistic-sounding talk Oxford UniversityPress, 1992), about Being based on the work of Frege. 11. Terence Penelhum, "Divine Necessity,"Mind 69 (1960), reprinted Basil Mitchell in (ed.), The Philosophy ofReligion (Oxford;Oxford UniversityPress, 1971). I quote from 12.Worries about a "pre-Kantiannotion of being," as I call it,certainlypreside in the critiquesofAquinas offeredby Kenny,O'Hear, Williams, and Penelhum.

13. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (trans. Norman Kemp Smith, London, text, pp. 184f.

J. F. Williams,

"Being,"

in C.

Taliaferro

and P. Quinn

(eds.),

The

Blackwell

And fun-loving Welshman." exist' is the work Welshmen

Macmillan, 1964), p. 504. 14. In listingtheseobjections I am largely drawingon what I have read by criticsof the thesis I defend. So there may, of course, be otherobjections ofwhich I an unaware. 15. Cf. A. N. Prior, "Is theConcept of Referential opacity Really Necessary?", Acta Philosophica Fennica 16 (1963). 16. It has been argued against me that the reason why sentences like "Fun-loving Welshmen exist" can just as well be rendered sentences like "SomeWelshmen are fun by loving" is because of "the tacitassumption thatthedomain of quantificationis a domain Without this assumption the equivalence would fail" (William of existing individuals. Valicella, "Reply to Davies; Creation and Existence," International Philosophical what Iwant to say about "_exist(s)" QuarterlyXXXI, June 1991). The idea here is that only makes sense on the assumption that I am sayingwhat can be said about existing things.If you like, the charge is that"it is precisely because every individualexists that thereis no need for thepredicate '_exists'" (Valicella, p. 222). But thischarge seems me to to we miss thepoint. I am saying thatif"Fun-loving Welshmen exist" is something assent to,we are surelyassenting to nothing thatcannot be expressed by "Someone is a

done I am adding that the work done by "_exist" in 'Fun-loving in "Someone is a fun-loving Welshman." by "someone"

AQUINAS,

GOD, AND BEING

519

to see that this is so. "X is bald" is true if, for example, of "domains" "John is language is true. "Fun-loving Welshmen exist" is true if, for example, "Idris is a fun-loving bald" true because is true. It is not, I suggest, "Idris exists and is a fun-loving Welshman" is true. Welshman"

And that We do not need the work is not to ascribe a propertyto an object or individual.

17. Gottlob Frege, The Foundations of Arithmetic, trans. J. L. Austin (Oxford: Blackwell, 1980), p. 65. 18. C. J.F.Williams, What isExistence?, pp. 54-5. Readers of Williams will recognize on how very indebtedI am to him for thoughts existence. 19. PeterGeach, God and theSoul (London:Routledge, 1969), p. 55. 20. Ibid. 21. You might say itnames a fictionalcharacter. But thischaracterisno realperson (no to real character)and thenamewe use inpurporting refertohim as ifhewere a realperson a within thecontextof thenovel David Copper is therefore name only in the sense that could be field it is used as if itwere such, as if it singled out someone of whom truths

asserted.

22. In Three Philosophers (Oxford:Blackwell, 1961), pp. 88f. P. T. Geach argues that inDe Ente etEssentia Aquinas is committedto theview thattheanswer to thequestion "What isGod?" is, effectively, "There is a God." In The Five Ways (London: Routledge, endorses Geach's reading adding, in opposition toGeach, that 1969), Anthony Kenny Aquinas never abandoned thisview.The mistakes involved inbothGeach's andKenny's readingofAquinas are helpfullyexposed inStephenTheron's paper "Esse" (New Scholas ticism 53, 1979). 23. De Ente etEssentia 1.1 quote from McDermott's translation. Timothy See Timothy McDermott (ed.), Aquinas: Selected philosophical Writings (Oxford;Oxford University he Press, 1993), pp. 9If. Aquinas draws attentionto thedistinction makes here in several on other places. See, forexample, (1) his commentary Aristotle'sMetaphysics, Book V, lectio9; (2) Summa Theologiae, la. 3, 4 ad 2; (3) Summa Theologiae, Ia.48, 2 ad 2.

24. Cf. Summa Contra Gentiles that being is not a genus, Summa Theologiae I, 24-26; cannot be of the essence existence 3a, 77, 1 ad. 2 ("Seeing or of either substance

28. These theses are defended by Aquinas inmany places. They aremost succinctly defended inSumma Theologiae, Ia, 2,1. For an account ofAquinas on these theses seemy Oxford UniversityPress, 1992), chs. 2 and 3. The Thought ofThomas Aquinas (Oxford; 29. Summa Theologiae, Ia, 12, 12; Ia, 88, 1; Ia, 88, 3. Blackfriarsedition of theSumma 30. Herbert McCabe, O.P., Appendix 3 tovol. 3 of the Theologiae (New York: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1964). 31. As philosophers, thatis.Aquinas has no problem about people talkingaboutGod on thebasis of revelationand with no special interest philosophy. in We may, he thinks, we believe many thingssaid ofGod even though do not know thattheyare true.For an account ofAquinas on revelationand believing, seemy The Thought ofThomas Aquinas, ch. 14. For a detailed discussion ofAquinas and what we can say ofGod positively, see de my "Aquinas onWhat God isNot." Revue Internationale Philosophie (forthcoming).

32. Cf. Summa theologiae, la, 2, 1.

la, 76, 2. la, 5, 5 ad. 3. Cf. la, 29, 2 ad. 5; Ia.50, Theologiae, 1. 76, 3; Ia, 104, 1. Cf. De principium Naturae, " on Aristotle's 27. Commentary "Peri Hermencias, I, X. 26. Summa Theologiae,

accident"). 25. Summa

5. Ia, 75, 6; Ia.76,

2; la,

520 BRIAN DAVIES,

O.P.

33.

Herbert

Religion and Philosophy (Cambridge; Cambridge UniversityPress, 1992), p. 45. As we whichAquinas isprepared to speak ofwhat is thecase where have seen, thereis a sense in what is inquestion is somethinglacking,e.g., theability to see. So he can make sense of "Blindness exists" and the like.But only because in sentences like this(if true)something is being said of somethingwhich can be thoughtof as "having esse** For example, unable to see. according to Aquinas "Blindness exists" is trueif someone is truly 34. According toP. T. Geach, Aquinas's talkof esse may be comparedwith what Frege has inmind when he speaks ofWirklichkeitand ofwhat iswirklich.This, saysGeach, is distinguishedby Frege fromtheexistence expressed by "there is a so-and-so" (es gibt ein _). Actuality is attributableto individualobjects.The existence expressed by "there is a is not (cf.God and theSoul, p. 65). But as faras I can discover, and certainlytogo _" byMichael Dummett's exposition of Frege inhis book Frege's Philosophy ofLanguage, 2nd edn., (London: Duckworth, 1981, ch. 14),Frege's distinction between the wirklich and that which is notwirklich is a distinction between that which is concreteand that which is abstract. Wirklich inFrege means "concrete."Frege nowhere thatI know of, suggests that of wirklich is an interpretation 'existent*. does at times speak of what is wirklich as He what is not suchmay still be being capable of acting upon the senses and he adds that objective. He says, for instance, thattheequator is not wirklich though it is objective in thatitdid not begin toexist onlywhen people startedtalking theequator (cf.The Foun of dations of Arithmetic,para. 26). But, again, this is not to suggest that wirklich is an

interpretation of 'existent*. 6.44 (trans. C. K. Ogden, 35. Tractatus 36. Tractatus 6.52. 37. he was Some famous philosophers seem went London: to have Routledge, 1922). Descartes, for instance,

McCabe,

O.P.,

"The

Logic

of Mysticism?I,"

in Martin

Warner

(ed.),

seems tohave thoughtthat discovered somethingabout himself he when discovering that

(is). Fortunately, Descartes on to ask what he was.

thought otherwise.

38. J. L. Austin once mischievously suggested thatexisting is like breathing,only Oxford UniversityPress, 1963), p. quieter.Cf. J.L. Austin, Sense and Sensihilia (Oxford:

68. Penelhum

39. The critiquesofAquinas offered AnthonyO'Hear, C. J.F.Williams, andTerence by

(see notes 9-11 above) seem to be based on contrary assumptions. O'Hear reads

God with being?considered as a highly general quality which Aquinas as identifying as cannot be appealed to as giving us any information towhat God is. Williams assumes that God of Aquinas is identifying with existence considered as a property objects or indi viduals. Penelhum thinksthat able to tell Aquinas takes "being" or "existence" tobe terms us what God is in the sense that"is human" can tellus what some human being is. to 40. Cf. the introduction Summa Theologiae la, 3.

41. 43. Cf. Summa 42. la, 3. Theologiae, 6.52. Tractatus, on Peter Lombard's Cf. Commentary

Sentences, "

I, d.37, I, XIV.

p.3, a.3; Sent.,

45. Cf. my "Aquinas on What God isNot," Revue Internationale Philosophie (forth de Cf. also my "Classical Theism and the Doctrine ofDivine Simplicity" inBrian coming). Davies, O.P. (ed.), Language, Meaning and God (London:GeoffreyChapman, 1987).

46. Summa Theologiae, la, 13, 11.

a.l; Sent., Iv, d.7, q.l, a.3. on Aristotle's 44. Commentary

I, d. 43, q.l,

"Peri Hermeneias,

You might also like

- American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 528Document5 pagesAmerican Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 528Thomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Ethics 2 Says, "Happiness (Felicitas) Is The Reward of Virtue." But Intellectual Habits Do Not Pay AttentionDocument9 pagesEthics 2 Says, "Happiness (Felicitas) Is The Reward of Virtue." But Intellectual Habits Do Not Pay AttentionThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Pre Algebra HandbookDocument107 pagesPre Algebra HandbookThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- The Education of A Tactical Meathead Getting Jacked and Making Money Part 1Document10 pagesThe Education of A Tactical Meathead Getting Jacked and Making Money Part 1Thomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Sacrament of Initiation and PenanceDocument44 pagesSacrament of Initiation and PenanceThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Mcinery Prudence and ConscienceDocument11 pagesMcinery Prudence and ConscienceThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- LATINA MI Secundus DiçsDocument2 pagesLATINA MI Secundus DiçsThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Training With Purpose Strength Training Considerations For AthletesDocument7 pagesTraining With Purpose Strength Training Considerations For AthletesThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Kentucky Strong Add 100 Pounds To Your PullDocument12 pagesKentucky Strong Add 100 Pounds To Your PullThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- By The Coach For The Coach The Ladies Take OverDocument9 pagesBy The Coach For The Coach The Ladies Take OverThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Keep It Simple Stupid Part 2 Assistance WorkDocument4 pagesKeep It Simple Stupid Part 2 Assistance WorkThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Are You Training Too HeavyDocument5 pagesAre You Training Too HeavyThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Ive Got 99 Problems But My Shoulder Aint OneDocument3 pagesIve Got 99 Problems But My Shoulder Aint OneThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Set and Rep Schemes in Strength Training Part 1Document7 pagesSet and Rep Schemes in Strength Training Part 1Thomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Reignite Progress With New ScienceDocument13 pagesReignite Progress With New ScienceThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Speed Vs SpeedstrengthDocument4 pagesSpeed Vs SpeedstrengthThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- My Return To PowerliftingDocument8 pagesMy Return To PowerliftingThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- High Powered JournalingDocument6 pagesHigh Powered JournalingThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Training With Purpose Programming Thoughts and Considerations For The New YearDocument5 pagesTraining With Purpose Programming Thoughts and Considerations For The New YearThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Training With Purpose IndividualizationDocument6 pagesTraining With Purpose IndividualizationThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Training With Purpose Deep Love or Cheap LustDocument5 pagesTraining With Purpose Deep Love or Cheap LustThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Developing Your Own Training Philosophy PDFDocument5 pagesDeveloping Your Own Training Philosophy PDFThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Monster Garage Gym Its Not Always The Strongest Lifter Who Wins PDFDocument9 pagesMonster Garage Gym Its Not Always The Strongest Lifter Who Wins PDFThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- The Flexible Periodization Method Out of Sight Out of Mind Part 3Document4 pagesThe Flexible Periodization Method Out of Sight Out of Mind Part 3Thomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Coach G What Is Your Philosophy Part 2 PDFDocument11 pagesCoach G What Is Your Philosophy Part 2 PDFThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Developing Your Own Training PhilosophyDocument5 pagesDeveloping Your Own Training PhilosophyThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Facts Needed To Prevent Hamstring StrainsDocument4 pagesFacts Needed To Prevent Hamstring StrainsThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- Elitefts Classic Training The Bench Press by Jim WendlerDocument5 pagesElitefts Classic Training The Bench Press by Jim WendlerThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- OffSeason Football Training For The NFL Working With Defensive Players From The Oakland Raiders PDFDocument3 pagesOffSeason Football Training For The NFL Working With Defensive Players From The Oakland Raiders PDFThomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- The Flexible Periodization Method Program Design With Kettlebells Part 2Document7 pagesThe Flexible Periodization Method Program Design With Kettlebells Part 2Thomas Aquinas 33No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Petroleum GeomechanicsDocument35 pagesPetroleum GeomechanicsAnonymous y6UMzakPW100% (1)

- Week 3: Experimental Design Energy Transfer (Mug Experiment)Document3 pagesWeek 3: Experimental Design Energy Transfer (Mug Experiment)Kuhoo UNo ratings yet

- Primary Reformer TubesDocument10 pagesPrimary Reformer TubesAhmed ELmlahyNo ratings yet

- Science Clinic Gr10 Chemistry Questions 2016Document44 pagesScience Clinic Gr10 Chemistry Questions 2016BhekiNo ratings yet

- EDOC-Benefits & Advantages of Applying Externally Gapped Line ArrestersDocument20 pagesEDOC-Benefits & Advantages of Applying Externally Gapped Line ArrestersEl Comedor BenedictNo ratings yet

- NETZSCH NEMO BY Pumps USADocument2 pagesNETZSCH NEMO BY Pumps USAWawan NopexNo ratings yet

- CT Selection RequirementsDocument35 pagesCT Selection RequirementsRam Shan100% (1)

- R Fulltext01Document136 pagesR Fulltext01vhj gbhjNo ratings yet

- Power System Stability-Chapter 3Document84 pagesPower System Stability-Chapter 3Du TrầnNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Computational Science and EngineeringDocument434 pagesLecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineeringmuhammad nurulNo ratings yet

- Barium Strontium TitanateDocument15 pagesBarium Strontium Titanatekanita_jawwNo ratings yet

- Foundations On Friction Creep Piles in Soft ClaysDocument11 pagesFoundations On Friction Creep Piles in Soft ClaysGhaith M. SalihNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving 1 Arithmetic SequenceDocument62 pagesProblem Solving 1 Arithmetic SequenceCitrus National High SchoolNo ratings yet

- Hospital Management System: A Project Report OnDocument24 pagesHospital Management System: A Project Report OnRama GayariNo ratings yet

- Sky Telescope 201304Document90 pagesSky Telescope 201304Haydn BassarathNo ratings yet

- CBIP draft meter standardsDocument22 pagesCBIP draft meter standardslalit123indiaNo ratings yet

- Module 11A-09 Turbine Aeroplane Aerodynamics, Structures and SystemsDocument133 pagesModule 11A-09 Turbine Aeroplane Aerodynamics, Structures and SystemsИлларион ПанасенкоNo ratings yet

- Frege: Sense and Reference One Hundred Years LaterDocument215 pagesFrege: Sense and Reference One Hundred Years LaterfabioingenuoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Pets in PreadolescentDocument17 pagesThe Role of Pets in PreadolescentshimmyNo ratings yet

- Experiment 1 - Friction Losses in PipesDocument34 pagesExperiment 1 - Friction Losses in PipesKhairil Ikram33% (3)

- Angle Facts Powerpoint ExcellentDocument10 pagesAngle Facts Powerpoint ExcellentNina100% (1)

- Profit Signals How Evidence Based Decisions Power Six Sigma BreakthroughsDocument262 pagesProfit Signals How Evidence Based Decisions Power Six Sigma BreakthroughsM. Daniel SloanNo ratings yet

- The Experimental Model of The Pipe Made PDFDocument4 pagesThe Experimental Model of The Pipe Made PDFGhassan ZeinNo ratings yet

- QFD PresentationDocument75 pagesQFD PresentationBhushan Verma100% (3)

- The Tom Bearden Website-StupidityDocument7 pagesThe Tom Bearden Website-StupiditybestiariosNo ratings yet

- Standard Rotary Pulse Encoder Operation Replacement SettingDocument8 pagesStandard Rotary Pulse Encoder Operation Replacement SettingGuesh Gebrekidan50% (2)

- 034 PhotogrammetryDocument19 pages034 Photogrammetryparadoja_hiperbolicaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Installation R2000iC210FDocument25 pagesTransportation Installation R2000iC210FMeet PAtel100% (2)

- Lab 8 - LP Modeling and Simplex MethodDocument8 pagesLab 8 - LP Modeling and Simplex MethodHemil ShahNo ratings yet

- List of Eligible Candidates Applied For Registration of Secb After Winter 2015 Examinations The Institution of Engineers (India)Document9 pagesList of Eligible Candidates Applied For Registration of Secb After Winter 2015 Examinations The Institution of Engineers (India)Sateesh NayaniNo ratings yet