Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DTCW 33 Love Madness

Uploaded by

bartneilerOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DTCW 33 Love Madness

Uploaded by

bartneilerCopyright:

Available Formats

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

Love Madness

by Dorothy Tennov

... L

ove, is nothing but a blind instinct . . . an appetite which directs us toward one object rather than another without our being able to account for our taste.

Ninon de LEnclos (Seventeenth Century)

Love is like a fever that comes and goes quite independently of the will. Stendhal The disease that is love brings into conflict our conscious intelligence and our basic will. Andre Maurois Another aspect of the pattern is that one falls in love not by design and conscious choice, but according to some accident of fate over which the victim has no control. Sidney M. Greenfield The idea that human beings are unique among creatures is so fully accepted that most people think of either people OR animals, not people AND other animals. With a logic and persistence similar to that which finds human beings special and superior, we have also tended to view ourselves as free of such constraints as are genetically imposed on other species. In contrast with the beast who is moved by blind instinct, human beings are rational and free of instinct, moved by individual inclinations that are rooted in experience, not by hardwired animal necessity. But if it were experience and reason alone that make us what we are, even many years of childhood are insufficient for the development of the complex emotional and behavioral repertoires shared by all humans whatever their culture. Granting that human beings do not operate through full-blown instincts in the sense of prewired complex patterns fully prewired, it is likely that human nature includes built-in tendencies that facilitate the learning of significant strategies for survival and reproduction. Culture does not operate on the proverbial blank slate. The concept that some aspects of mental life are special function brain

A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It Limerence:

mechanisms, or modules, has become widely accepted due to confirmatory observations by neuroscientists and evolutionary psychologists, and if any human actions are under the direct influence of the genes, surely those related to reproduction are likely candidates.

Limerence Defined

he subjective experience identified by the term limerence as revealed in personal testimonies 10 is such a candidate. The emotional state generally displayed the following elements: intrusive thinking about the person who is the object of desire (the limerent object or LO), acute longing for reciprocation from LO, dependency of mood on LOs actions or, more accurately, interpretation of LOs actions strictly in terms of the probability of reciprocation; inability to react limerently to more than one person at a time; some fleeting relief from unrequited limerent passion through vivid imagination of action by LO from which reciprocation can be inferred; fear of rejection and shyness in LOs presence, especially at the beginning and whenever uncertainty strikes; intensification through adversity (at least, up to a point); acute sensitivity to any act, thought or condition that can be interpreted favorably; extraordinary ability to find reasonable explanations for why the neutrality or even rejection that the disinterested observer might see in LOs behavior is in fact a sign of hidden passion; an aching of the heart (a region in the center front of the chest) when uncertainty is strong, buoyancy (a feeling of walking on air) when reciprocation seems evident; a general intensity of feeling that often leaves other concerns in the background; and a remarkable ability to emphasize what is truly admirable in LO and to avoid dwelling on less favorable characteristics. Limerence theory holds, first, that the underlying mechanism of limerence is universal. Second, the state of limerence comes into being automatically when barriers to receptivity are down and a likely object appears. Third, as limerence takes hold, there is a predictable regularity of response to the complex of external circumstances 11. The persons experience thereafter depends on, for example, how strongly it seems that the hoped-for reciprocation will occur. The basis for hope is largely, although perhaps not entirely, a matter of LOs actions. Small doses of attention from LO increase the intensity of the limerence experience. Finally, when reciprocation occurs, it leads to a unique-type euphoria. This is what the early nineteenth-century writer, Stendhal, called the greatest happiness. This euphoria is followed by a union that may be stable or unstable, and that may or may not endure.

10 11

For a description of the original research and findings, see Tennov (1979). Before writing Love and Limerence, I drew a diagram of it, but the publishers declined to include it because it looked like a graph but it wasnt scientific. It was just something made up. Someday Id like to say more about that response. It has to do with the scientific mystique and with innumeracy.

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

Through the Purview of Human Evolution

imilarity of experience of limerence among many types of people in many cultures and its involuntariness suggest that it is well rooted in the very nature of humanness (Harris, 1995; Brown, 1966). In many species, mates form attachments that aid the survival of offspring. But by what mechanism are we humans guided toward our partners? Our ancestors mated successfully but they also avoided inbreeding (mating with very close relatives) by a lack of sexual attraction for their closest childhood familiars, who were probably related. Many people have seen being in love as a madness.12 Not everyone considers it illogical or abnormal, but even so strong an advocate of romantic love as Stendhal spoke of it as a disease. Interviewees who had (fully) recovered from limerence agreed. If limerence was replaced by an affectional bonding with their LO they might reminisce about the wonderful, ecstatic, honeymoon days which were gradually replaced by an affectionate and companionable partnership, We were very much in love when we were married; today we love each other very much. How often and under what conditions limerence is followed by satisfactory companionship is a subject for future research. People are either limerent or not and, if limerent, then what happens to them is not under their control. They are caught in the grip of a madness. A hallmark of limerence is that there is only one LO (at a time). When that person fails to reciprocate, the result may be long hours of sustained lovesickness relieved only slightly, by achieving the limerence goal in imagination. And when all bases for hope have been exhausted, there may come a time when the sufferer has had enough and wants to end the pain of prepossession only to find and this is the madness that thoughts of LO cannot be turned off. Scarlett OHara (who said she would think about it tomorrow, might have been over-optimistic, or she might have mainly been suffering loss of pride and fear of being left alone in her old age. If limerent, she will not stop thinking about Rhett, and will probably relapse to alcoholism in an attempt to stop the anguish. The intrusions and literal aches of unfulfilled desires, and the lost pieces of ones life during which the mind traveled relentlessly down a dead-end course force recognition that there are limits to human self-control. Limerence is not something a person does, any more than is the common cold. At the beginning of my research, I was convinced by the multitudinous contradictions in what has been said and written about love that it appears in numerous guises, depending on time, circumstance, and persons13. In contrast, I found sameness across diverse situations. Limerence is limerence wherever its found, and I began to apply ideas that were emerging from the biological sciences, especially the study of hereditary mechanisms, genetic theories, and evolutionary disciplines that cross the traditional barriers between psychology and biology. Scientists consider the possibility that, over the course of biological history, certain social behavioral tendencies have evolved along with the more easily observable physiological features (Barash, 1975), but the relationships among inborn tendencies and environmental influences are complex (Maynard Smith and Szathmary, 1995). In many species, learning appears to be involved in the development of basically instinctive reactions (Wilson, 1975). Very few complex behavioral reactions are fully programmed in the nervous system of any of the more complex animals. Although universality does not necessarily imply innateness, evidence suggests a clear genetic base for certain human traits. For example, in a survey of sculpture and paintings from various parts of the world and different historical eras, it was found that roughly 93 percent

A 750-word magazine article about limerence research using the term love madness rather than limerence, brought a response of several hundred letters from people who wrote much the same kinds of things as did readers of Love and Limerence. And several of those said they didnt even wait to finish the book. The implication? That the condition is well known. 13 The general attitude is that love is so complicated and so individual that anything said about it is probably true for some people, or under some conditions (e. g., Wilson and Nias, 1976).

12

A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It Limerence:

were rendered with the right hand, a proportion maintained regardless of historical era or culture (Coren and Porac, 1977), evidence that favors the theory of a genetic predisposition to righthandedness in humans. I see limerence as a normal and ordinary feature of the human species, and my approach to its study is basically that of the ethologist who observes animals in natural settings and analyzes the behavior from an evolutionary perspective (Bateson and Hinde, 1976). A main difference between limerence research with human beings and traditional ethological studies is that the observations on which limerence theory is based come by means of self-reports. Any pattern observed, whether it be salmon migration, the retrieval of pups that stray from the maternal rats nest, courtship displays by certain birds, or limerence in humans, can be considered in the light of how the specific behavior was adaptive. Evolution is not an ever-upward drive toward perfection. This is not to say that it is a totally random process. If it were, there would be no evolving. The environment selects from among the variations chance throws out for consideration. Thus the process of natural selection is bungling, inefficient, and often cruel. Still, the fundamental principle is simple: the inherited you (or genotype) is the final (up to now, that is) product of traits that have been selected by nature in a continuous line through the generations from your parents to their parents and so on through all the organisms that were your progenitors back to the primordial substance in which the spark of life first began on this isolated planet (Dawkins, 1976). Step by minute step across eons of incredible duration, life proliferated and changed through the single essential principle of selection. If a behavior or a state is genetically programmed, it is one that enhanced or, at least, did not in any way diminish the ability of organisms carrying its controlling gene or genes to pass that hereditary substance to the next generation (Williams, 1966). The traits of courtship, mating, and the nature and duration of pair bonds (if any) that exist between partners, sexual behavior, and child rearing have been the focus of many ethological, evolutionary psychology and sociobiological studies (e.g., Symons, 1979).

Disadvantageous Remnants of the Past

volutionary thinking can also explain the existence of less desirable traits. For example, motion sickness would appear to be an evolutionary anomaly. However, evolutionary theorists speculate about its having had advantages in an earlier time, with vestigial carry-over. Humans are not alone. Some birds, horses, monkeys, and even certain fish also exhibit signs of motion sickness. But other species rabbits and guinea pigs do not. This presents a confusing array of possibilities. In what way is a monkey like a codfish but not like a rabbit? Treisman (1977) reasoned that malaise and vomiting in response to some forms of motion is unlikely to be sheer accident. One would expect natural selection to have eliminated such a disruptive reaction unless there exists or once existed positive reason for its persistence. Treisman reasons that, though malaise and vomiting are inappropriate in the case of motion it would have been adaptive if it eliminated ingested poisons. It turns out that certain types of trigger conditions are similar to those produced by the ingestion of toxins. Corroborating evidence is the finding that motion sickness does not occur in infancy, when food is likely to be free of toxins and when an infant is frequently carried about, or in species that subsist on specialized diets. Although the

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

malaise does not itself assist the process of toxin elimination, it may also be an adaptation which serves to teach the organism to stay away from such substances. Thus vomiting and malaise are part of an early warning system that is inappropriate as a response to motion, but important in inhibiting the ingestion of toxins. Treismans evolutionary hypothesis is that motion sickness is an accidental by-product of the organisms response to certain head and eye movements that occur in food poisoning. Thus, evolutionary thinking assists the scientific process of theorizing in more complex ways than simply conjecturing about survival value.14 The force behind the way a particular trait functions to permit its own survival through a continual supply of individuals who carry the genes for it is known as the ultimate cause of the adaptive process. The specific way the trait functions is known as the mechanism or proximate cause 15. For what ultimate cause might the state of limerence be a proximate cause? Why were limerent people successful, maybe more successful than others, in passing their genes to succeeding generations? Limerence may have evolved back a few hundred thousand or a million years ago when human heads grew larger and fathers who left mother and child to fend for themselves were less reproductively successful in the long run, that is (Morgan, 1995). Did limerence evolve to cement a relationship between parents for long enough to get the offspring up and running? To understand why the environment of our ancestors selected limerence, we might consider the behavior it induces. Like motion sickness, some effects of limerence may now be undesirable. Some aspects of limerence are antisocial, even socially disruptive. It deflects interest from affairs of business, of state, and even of family. In the midst of battle, the soldiers despair over a letter of rejection from LO is not forgotten. A king gives up his crown. An artists career languishes. But the usual result of limerence is mating, not merely sexual interaction but commitment, the establishment of a shared domicile in the form of a cozy nest built for the enjoyment of ecstasy, for reproduction, and for the rearing of children. In human beings limerence does not ensure the permanent monogamy found in some other species, but its usual duration of several years enables a woman to keep a man around at least for a time (Money and Ehrhardt, 1972). Voluntary testimony suggests that a lower limit for the duration of limerence may be as long as three years, at least among mature adults, and that there is no upper limit. Not that limerence is the only mechanism in the human system to help offspring on their way in life. There is, for example, an inborn response to creatures perceived as cute, creatures with such features as large eyes and a head that is out of proportion to the rest of the body. These characteristics are shared by most mammalian young (Wickler, 1973), and human beings are not the only mammals to respond affectionately and protectively to cuteness in members of their own and other species. Many animals also form pair bonds. Some species mate for life, and others for only a season. Reproductive patterns also differ among species in care of the offspring. By the time the young of some species emerge from egg or pupa, the parents have long since departed, and the generations never meet except by chance. The new generation fends for itself from the outset. But the range of strategies is wide. Wickler described the behavior of the native European bird, the Panurus biamicus (the bearded tit):

Other sources of information concerning the unfortunate leavings of prior adaptations, see Morgan (1993) and Nesse and Williams (1995). 15 The term proximate case can refer to mechanisms at any lower level. Limerence theory focuses on the level of experience. There has been much speculation, but, as yet, few definitive conclusions regarding the physiological level (Fisher, 1992).

14

A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It Limerence:

The partners spend their whole lives in very close permanent monogamy and can only be separated by force.... Two or three days after the male has concentrated his attention on a particular female and she has tolerated it willingly, the matter is decided, and the two sleep closely clumped together at night and not with brothers and sisters as before. During cleaning and drinking, foraging, bathing, and sleeping, the one will hardly leave the side of the other, and they continually preen each others ruffled feathers. If one flies a grass blade farther away, the other will land beside it a moment later. If one loses sight of the other, it will call loudly until they have found each other again. Although two months later the call alone is enough . . . so that they can tolerate a separation of a few meters. But the marital partners sleep close together throughout their life. If one dies, the other will fly around excitedly, searching and constantly calling and becoming extremely agitated the moment it hears the call of another bearded tit or a sudden rustling in the bushes, as though hoping that at last its partner was about to land beside it (pp. 95-96). The duration of a typical sustained pairing in humans is proportionately shorter than the lifelong attachment of these little birds. On the other hand, who can say that what the bearded tit feels for its mate is not basically the same as what the human limerent feels for LO; the outward signs look very similar. Konrad Lorenz, founder of ethology, noted in geese that Such a bond may arise explosively, almost before one has realized it, joining two individuals together for life. We say then . . . that the two have fallen in love (Lorenz, 1966). The term imprinting has referred to a kind of attachment at first sight in which young birds thereafter follow whatever it is that appeared in their visual field at a certain critical period during early development. Under natural conditions, that stimulus is usually the mother bird, but in the laboratory, chicks and ducklings have become attached to red rubber balls, and experimenters 16. This phenomenon is a good example of built-in ability to adapt to unusual environments. If something happens to the mother, the newborn animal loves the father, foster mother, or whoever happens to be around at the time, (even a predator, I assume, but that would be a short-lived love affair.) The image of geese hopping along in the wake of an experimenter (Lorenz in a famous photograph) excited the imagination of many behavioral scientists, some of whom attempted to detect the phenomenon in other species and at other times in the life span. One investigator (Salk, 1962) reported prenatal imprinting of the human infant to the mothers heartbeat which he felt might predispose the child to certain musical tempos in later life, whereas others contended that imprinting, when it occurred, was limited to visual, not auditory stimuli. Controversy broke out in scientific journals concerning appropriate use of the term imprinting when some researchers seemed ready to apply the label wherever the faintest degree of resemblance to the behavior of geese appeared (Sluckin, 1973). At least one attempt to repeat the heartbeat research was unsuccessful. Although there may be controversy in the details, evidence is abundant that environmental conditions at a certain time of life can affect the organism thereafter. The effect ranges from prenatal susceptibility to certain substances during the first weeks of gestation to language learning, and to the types of attachments that develop among family and group members. It was inevitable that someone would wonder whether falling in love could be classified as imprinting. Applying findings of geneticists, embryologists, endocrinologists, neuroendocrinologists, psychologists, and anthropologists in an analysis of gender identity and focusing on the interactions between heredity and environment, Money

16

Of course, it isnt that simple. For a discussion of imprinting research, see Bateson (1987).

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

and Ehrhardt (1972) also describe romantic love to include prepossession with and emotional dependency on the words, looks, and actions of the loved person. Also consistent with limerence research is their finding that falling in love does not differ between the sexes and their assumption that it is both involuntary and largely genetically determined. Although the first in love experience may precede or follow the onset of hormonal puberty, Money and Ehrhardt clearly assume a biological basis for falling in love. Better than the term imprinting, which refers to events that occur at a certain time during development, limerence resembles another ethological concept: the fixed action pattern (Salzen, 1966). At a certain point during the transition from nonlimerence to limerence, an event takes place that Stendhal called crystallization in which the mind fashions an image of perfections from LOs actual attractive features. The process of redefining LO in the best light usually is one of emphasis rather than invention.

n impressive case for the existence of involuntary and unconscious mechanisms in humans is provided by mate selection among people raised in Israeli kibbutzim (Talmon, 1973). Children who are reared together do not in later life regard each other as erotically desirable. Despite parental preferences, data on 2,769 marriages that took place in second-generation offspring of kibbutzim dwellers show no intermarriages between persons reared together uninterruptedly during the first five years. Childhood intimacy prevented adult limerence. Such automatic mechanisms that cause animals to respond to circumstances with a complex yet distinct reaction is likely to be a species universal. This idea is consistent with the idea that limerence is a human universal rather than the result of a culture saturated with romantic love in its stories and songs. Anti-incest imprinting has value, because mating between too-close relatives tend to result in inferior offspring. (Observations of higher primates reveal disinclination toward mating on the part of mothers and male offspring.) Cultures differ in whether they condone or condemn romantic love as well as in relation to who is and is not an acceptable marriage partner or whether the selection is made by the individuals or by their elders. The kibbutzim finding does not rule out cultural influence over some aspects of limerence, but it clearly supports the notion that limerence is at least partly governed by forces that are not under social control.

The Mechanism of Incest Taboo

Physical Attractiveness 17

The role of physical attractiveness in romantic attachment and human courting behavior has been researched by psychologists and sociologists. In study after study, the conclusion was the same as the one we all intuit: better-looking people have the advantage. Because physical features contribute so heavily to attractiveness, the person in limerence becomes greatly even extraordinarily concerned

17

Attractiveness is one of several concepts in limerence theory that are without unequivocal referents. (Other terms in this category are reciprocation and unrequited). Because these terms are currently without objective referents, limerence theory can rightly be said to lack some attributes of a scientific theory. However, I concur with Calvin (1996) and other scientists who see speculation as an integral part of the scientific process, the only constraint being that known facts are not violated.

A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It Limerence:

about his or her own facade. As one interviewee put it, in an attempt to elicit similar limerent reactions in another, they will alter their posture and try to hide baldness or what they believe to be their unattractive facial features. Some people develop nervous gestures designed to distract the viewer from the ugly sight. Hair dyes, makeup, attire, diet, and exercise regimens are regularly featured in popular magazines because they make the user feel more able to stimulate the limerent reaction in LO. When limerence is intense, no aspect of living is as important as is hope of achieving the persistently envisioned goal of reciprocation. Surely it is no accident that the time of life during which, by group consensus, human beings are most attractive post adolescence and early adulthood is also the time at which most reproductive matings are initiated. Physical attractiveness and youth are rough indications of good health and other attributes that relate to breeding capability and thus genetic fitness. But the question can be raised as to whether producing healthy and desirable children would be more likely if it did not depend on superficial physical traits when other features of the individuals involved may be of greater importance? The answer might be that the large role physical attractiveness plays in mate selection permits traits uncorrelated with beauty to be selected as a by-product of the admiration of beauty. That is, there may be greater genetic benefit from not allowing individuals to choose mates entirely by conscious, rational means. What appears to be a good match by such criteria might in fact amount to a genetically unfit form of inbreeding. Physical attractiveness draws individuals to a mate who may be unlike themselves in other respects. The ability of cultures to change standards of beauty seems to be limited to a certain range. That it occurs at all suggests interplay between environmental influence and genetic makeup, an interplay that scientists have found in abundance in all cultures (Wilson, 1975). Whatever factors govern an individuals selection of a particular person as LO, limerence cements the limerent response to that person and locks the gates against competitors. This exclusivity weakens the effect of physical attractiveness, since once limerence has taken hold the most beautiful individual in the world cannot compete with LO. Thus, persons who vary from one another across a wide range of physical appearances can still manage to stimulate the limerent reaction. When I gave my first paper on my research on romantic love (Tennov, 1973), as I called it then, a man in the audience reacted with indignation at the idea of exposing the sacred subject of love to the cold light of science. In the two decades since Love and Limerence was published, I have had the opportunity to witness the reactions of many people to the idea of falling in love as falling into an automatic, involuntary condition in which ones thoughts and ones happiness is under the control of another 18. Some people, mistakenly, but understandably, have assumed that limerence, referred to an extreme reaction. Although limerence can be extremely painful and extremely pleasant, extreme feeling is not its definition. Limerence is a state in which the Laws of Limerence are operative. How pleasant or painful it turns out to be in any given instance depends on force of circumstance.

18

The social, ethical, as well as scientific implications of limerence theory are dealt with elsewhere (Tennov, 1986, 1979) c.f. Endnote below

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

Bibliography

Bach, George R., and Ronald M. Deutsch (1971) Pairing. New York: Avon Books. Barash, David P. (1975) Behavior as Evolutionary Strategy. Science 190:1084-85. _______ (1977) Sociobiology and Behavior. New York: Elsevier North-Holland Bateson, P. P. G., and R. A. Hinde (1976) Growing Points in Ethology. New York: Cambridge University Press. _______ (1987) Imprinting, in Richard L. Gregory, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 355-357. Bloom, Martin (1967) Toward a Developmental Concept of Love. Journal of Human Relations 15:24663. Brown, Donald E. (1991) Human Universals New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. _______ (1996) (Personal communication.) Buss, David (1995) The Evolution of Desire. NY: Basic Books. Calvin, William H. (1996) The Cerebral Code: Thinking a Thought in the Mosaics of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Cziko, Gary (1996) Without Miracles Dawkins, Richard (1976) The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dennett, Daniel C. (1995) Darwins Dangerous Idea. New York: Simon and Schuster. Fisher, Helen. (1992). Anatomy of Love: The natural history of monogamy, adultery, and divorce. NY: W. W. Norton. Harris, Helen (1995) Rethinking Heterosexual Relationships in Polynesia: A case Study of Mangaia, Cook Island, in William Jankowiak, ed. Romantic Passion: A Universal Experience? New York: Columbia University Press. Hunt, Morton M. (1959) The Natural History of Love. New York: Alfred A. Knopf,. Kirkpatrick, Clifford, and Theodore Caplow (1945) Emotional Trends in the Courtship Experience of College Students as Expressed by Graphs, with Some Observations on Methodological Implications. American Sociological Review 5:619-26. Maurois, Andre (1944) Seven Faces of Love. New York: Didier Publishing Co. Greenfield, Sidney M. (1965) Love and Marriage in Modern America, The Sociological Quarterly 6:363364 Lorenz, Konrad (1966) On Aggression translated by Marjorie Latzke. London: Routledge. Maynard Smith, John and Eors Szathmary (1995) The Major Transitions in Evolution. New York: W. H. Freeman. Money, John and Anke A. Ehrhardt (1972) Man and Woman, Boy and Girl: The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It Limerence:

Morgan, Elaine (1993) The Scars of Evolution: What Our Bodies Tell Us about Human Origins. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. Morgan, Elaine (1995) The Descent of the Child: Human Evolution from a New Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. Nesse, Randolph M. and George C. Williams (1995) Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine. New York: Times Books. Riegel, Michelle Galler (1977) Monogamous mammals: variations of a scheme, Science News 112:7678. Salk, Lee (1962) Mothers Heartbeat as an Imprinting Stimulus, Transactions of The New York Academy of Science, 24: 753-63. Salzen, Eric (1996) Introduction to the Routledge Edition of Konrad Lorenzs On Aggression translated by Marjorie Latzke. London: Routledge Sluckin, W. (1974) Imprinting Reconsidered, Bulletin of the British Psychological Society 27: 447-51. Stendhal (1975) Love. Translated by Gilbert and Suzanne Sale; Introduction by Jean Stewart and B. C. J. G. Knight. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. Symons, Donald (1979). The Evolution of Human Sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Talmon, Yonina (1964) Mate Selection in Collective Settlements, American

Sociological Review 29: 491-508.

Tennov, Dorothy (1973) Sex Differences in Romantic Love and Depression Among College Students. Proceedings of the 81st Animal Convention of American Psychological Association, 8:421-22. _________ (1979) Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love New York: Stein and Day. _________ (1985) Limerence Retreat (unbpublished, but widely distributed). __________ (1997) Limerence and Human Nature Science. (in preparation) Treisman, Michel (1977) Motion Sickness: An Evolutionary Hypothesis, Science 197: 493-95. Washburn, Sherwood L. (1978). Human Behavior and the Behavior of Other Animals. American Psychologist 33: 405-18. Wickler, Wolfgang (1973) The Sexual Code Garden City, N. J.: Anchor Press/Doubleday Williams, George C. (1966). Adaptation and Natural Selection. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Wilson, Glenn and David Nias (1976) The Mystery of Love: How the Science of Sexual Attraction Can Work for You. New York: Quadrangle

Endnote to Love Madness

Expansion of Footnote AboveFor a description of the original research and findings, see Tennov (1979). Before writing Love and Limerence I drew a diagram of it but the publishers declined to include it because it looked like a graph but it wasnt scientific. It was just something made up. Someday Id like to say more about that response. It has to do with the scientific mystique and with innumeracy.

The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov

A 750-word magazine article about limerence research using the term love madness rather than limerence, brought a response of several hundred letters from people who wrote much the same kinds of things as did readers of Love and Limerence. And several of those said they didnt even wait to finish the book. The implication? That the condition is well known. The general attitude is that love is so complicated and so individual that anything said about it is probably true for some people, or under some conditions (e. g., Wilson and Nias, 1976). Other sources of information concerning the unfortunate leavings of prior adaptations, see Morgan (1993) and Nesse and Williams (1995). The term proximate case can refer to mechanisms at any lower level. Limerence theory focuses on the level of experience. There has been much speculation, but, as yet, few definitive conclusions regarding the physiological level (Fisher, 1992).

F lowers by Dorothy Tennov

October 4, 2001

You might also like

- DTCW 42 Concept LimDocument7 pagesDTCW 42 Concept LimbartneilerNo ratings yet

- Crazy for love: exploring the links between passionate love and mental illnessDocument3 pagesCrazy for love: exploring the links between passionate love and mental illnessJohn Rose100% (1)

- DTCW 03 ReviewsDocument8 pagesDTCW 03 ReviewsbartneilerNo ratings yet

- Pathologies of the Self: Exploring Narcissistic and Borderline States of MindFrom EverandPathologies of the Self: Exploring Narcissistic and Borderline States of MindNo ratings yet

- Brennan Transmission Affect CH 6Document17 pagesBrennan Transmission Affect CH 6GustavoVargasNo ratings yet

- Into the Abyss: A neuropsychiatrist's notes on troubled mindsFrom EverandInto the Abyss: A neuropsychiatrist's notes on troubled mindsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Totem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNo ratings yet

- The Intermediate Sex, A Study Of Some Transitional Types Of Men And WomenFrom EverandThe Intermediate Sex, A Study Of Some Transitional Types Of Men And WomenNo ratings yet

- 3 Three Essays On The Theory of Sexuality Author Sigmund FreudDocument83 pages3 Three Essays On The Theory of Sexuality Author Sigmund FreudHoàng Ngọc PhúcNo ratings yet

- Anna Freud - About Losing and Being LostDocument12 pagesAnna Freud - About Losing and Being Lostljdinet100% (1)

- Meet Your Political Mind: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorFrom EverandMeet Your Political Mind: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Roe Cooper Lorimer Elsaesser Critical EvaluationDocument75 pagesRoe Cooper Lorimer Elsaesser Critical EvaluationDBCGNo ratings yet

- Moral Minds: The Nature of Right and WrongFrom EverandMoral Minds: The Nature of Right and WrongRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (40)

- Fighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and ConsciousnessFrom EverandFighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and ConsciousnessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Reality Of Our Natures And The Nature Of Our Realities The Reality Of Our Natures And The Nature Of Our Realities: TROONATNOORFrom EverandThe Reality Of Our Natures And The Nature Of Our Realities The Reality Of Our Natures And The Nature Of Our Realities: TROONATNOORNo ratings yet

- Dorothy Tennov - Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in LoveDocument305 pagesDorothy Tennov - Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in LoveLucas Morais100% (1)

- Hylozoics LiteratureDocument129 pagesHylozoics LiteratureSean HsuNo ratings yet

- TOTEM & TABOO: Resemblances between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodFrom EverandTOTEM & TABOO: Resemblances between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNo ratings yet

- DTCW 24 About TrialDocument6 pagesDTCW 24 About TrialbartneilerNo ratings yet

- I Never Metaphor I Didn't Like: A Comprehensive Compilation of History's Greatest Analogies, Metaphors, and SimilesFrom EverandI Never Metaphor I Didn't Like: A Comprehensive Compilation of History's Greatest Analogies, Metaphors, and SimilesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- What's in It For Me? Discover The Universal Empathy of HumanityDocument8 pagesWhat's in It For Me? Discover The Universal Empathy of Humanityarajah143No ratings yet

- Meet Your Mind Volume 1: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorFrom EverandMeet Your Mind Volume 1: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Getting Through: The Wit, Wisdom, and Ignorance of Robert Newton TaylorFrom EverandGetting Through: The Wit, Wisdom, and Ignorance of Robert Newton TaylorNo ratings yet

- Paranormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological ExaminationFrom EverandParanormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological ExaminationRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- A Critical Analysis of Patriotism As an Ethical ConceptFrom EverandA Critical Analysis of Patriotism As an Ethical ConceptNo ratings yet

- Totem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksNo ratings yet

- The Awakening and the Continuum: A Manual of Life Concerning the Exposure of All Materialism, Enigmas and MysteriesFrom EverandThe Awakening and the Continuum: A Manual of Life Concerning the Exposure of All Materialism, Enigmas and MysteriesNo ratings yet

- Psychology of The Unconscious: A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoFrom EverandPsychology of The Unconscious: A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoNo ratings yet

- BROWN, Donald E. - Human UniversalsDocument12 pagesBROWN, Donald E. - Human UniversalsMONOAUTONOMONo ratings yet

- Michael Rennie: New York September 1987 From WebsiteDocument6 pagesMichael Rennie: New York September 1987 From WebsiteChaxxyNo ratings yet

- THC116 - Module1 - Lesson ProperDocument9 pagesTHC116 - Module1 - Lesson ProperRashly Virlle SullanoNo ratings yet

- Liberal Democracies' Recognition of Tensions Between Patriarchy and Equal LibertyDocument33 pagesLiberal Democracies' Recognition of Tensions Between Patriarchy and Equal LibertyAndrea LopezNo ratings yet

- The Man Who Tasted ShapesDocument23 pagesThe Man Who Tasted Shapesosamelosa2020No ratings yet

- DTCW 41 Pha Lim ResDocument3 pagesDTCW 41 Pha Lim ResbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 35 Lim QandaDocument6 pagesDTCW 35 Lim QandabartneilerNo ratings yet

- Commentaries: Conclusion Regarding ReligionDocument6 pagesCommentaries: Conclusion Regarding ReligionbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 39 Rho Hal HomDocument13 pagesDTCW 39 Rho Hal HombartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 30 Lim TheoryDocument10 pagesDTCW 30 Lim TheorybartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 37 Tho Abo Hum NatDocument6 pagesDTCW 37 Tho Abo Hum NatbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 40 Can Lim Stu SciDocument3 pagesDTCW 40 Can Lim Stu ScibartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 38 Forced ConclusionsDocument2 pagesDTCW 38 Forced ConclusionsbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 36 Racial ScienceDocument2 pagesDTCW 36 Racial SciencebartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 32 Will We Wake UpDocument2 pagesDTCW 32 Will We Wake UpbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 34 Break RoomDocument21 pagesDTCW 34 Break RoombartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 28 Lim RetreatDocument33 pagesDTCW 28 Lim RetreatbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 29 Lim Res EthologyDocument6 pagesDTCW 29 Lim Res EthologybartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 25 Reviews LandLDocument2 pagesDTCW 25 Reviews LandLbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 26 Science ReligionDocument3 pagesDTCW 26 Science ReligionbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 24 About TrialDocument6 pagesDTCW 24 About TrialbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 27 Letter From ReaderDocument1 pageDTCW 27 Letter From ReaderbartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 23 B3Q A3Document13 pagesDTCW 23 B3Q A3bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 22 B3Q A2Document13 pagesDTCW 22 B3Q A2bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 18 Trial A3 c13Document14 pagesDTCW 18 Trial A3 c13bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 21 B3Q A1Document26 pagesDTCW 21 B3Q A1bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 16 Trial A2 c11Document7 pagesDTCW 16 Trial A2 c11bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 20 Trial A3 C15 EpilogueDocument4 pagesDTCW 20 Trial A3 C15 EpiloguebartneilerNo ratings yet

- Act Iii: Love Control: Chapter XII - Peter's EpiphanyDocument10 pagesAct Iii: Love Control: Chapter XII - Peter's EpiphanybartneilerNo ratings yet

- Act Ii The Trial: Act Ii The Trial:: Chapter VIII - PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesAct Ii The Trial: Act Ii The Trial:: Chapter VIII - PsychotherapybartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 19 Trial A3 c14Document10 pagesDTCW 19 Trial A3 c14bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 15 Trial A2 c10Document14 pagesDTCW 15 Trial A2 c10bartneilerNo ratings yet

- DTCW 14 Trial A2 c9Document12 pagesDTCW 14 Trial A2 c9bartneilerNo ratings yet

- KoyoDocument4 pagesKoyovichitNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Specifications For Fiberbond ProductDocument8 pagesMechanical Specifications For Fiberbond ProducthasnizaNo ratings yet

- HVCCI UPI Form No. 3 Summary ReportDocument2 pagesHVCCI UPI Form No. 3 Summary ReportAzumi AyuzawaNo ratings yet

- Tds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Document3 pagesTds G. Beslux Komplex Alfa II (25.10.19)Iulian BarbuNo ratings yet

- Handout Tematik MukhidDocument72 pagesHandout Tematik MukhidJaya ExpressNo ratings yet

- GLOBAL Hydro Turbine Folder enDocument4 pagesGLOBAL Hydro Turbine Folder enGogyNo ratings yet

- LTE EPC Technical OverviewDocument320 pagesLTE EPC Technical OverviewCristian GuleiNo ratings yet

- Panasonic 2012 PDP Troubleshooting Guide ST50 ST Series (TM)Document39 pagesPanasonic 2012 PDP Troubleshooting Guide ST50 ST Series (TM)Gordon Elder100% (5)

- Helmitin R 14030Document3 pagesHelmitin R 14030katie.snapeNo ratings yet

- Acuity Assessment in Obstetrical TriageDocument9 pagesAcuity Assessment in Obstetrical TriageFikriNo ratings yet

- CIRC 314-AN 178 INP EN EDENPROD 195309 v1Document34 pagesCIRC 314-AN 178 INP EN EDENPROD 195309 v1xloriki_100% (1)

- Rectifiers and FiltersDocument68 pagesRectifiers and FiltersMeheli HalderNo ratings yet

- Lyceum of The Philippines University Cavite Potential of Peanut Hulls As An Alternative Material On Making Biodegradable PlasticDocument13 pagesLyceum of The Philippines University Cavite Potential of Peanut Hulls As An Alternative Material On Making Biodegradable PlasticJayr Mercado0% (1)

- Lincoln Pulse On PulseDocument4 pagesLincoln Pulse On PulseEdison MalacaraNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic Weld Examination ProcedureDocument16 pagesUltrasonic Weld Examination ProcedureramalingamNo ratings yet

- Lightwave Maya 3D TutorialsDocument8 pagesLightwave Maya 3D TutorialsrandfranNo ratings yet

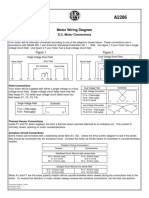

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocument1 pageMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594No ratings yet

- SECTION 303-06 Starting SystemDocument8 pagesSECTION 303-06 Starting SystemTuan TranNo ratings yet

- Metal Framing SystemDocument56 pagesMetal Framing SystemNal MénNo ratings yet

- 2 - Elements of Interior DesignDocument4 pages2 - Elements of Interior DesignYathaarth RastogiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 - Energy Transfers: I) Answer The FollowingDocument3 pagesChapter 16 - Energy Transfers: I) Answer The FollowingPauline Kezia P Gr 6 B1No ratings yet

- IS 4991 (1968) - Criteria For Blast Resistant Design of Structures For Explosions Above Ground-TableDocument1 pageIS 4991 (1968) - Criteria For Blast Resistant Design of Structures For Explosions Above Ground-TableRenieNo ratings yet

- Are Hypomineralized Primary Molars and Canines Associated With Molar-Incisor HypomineralizationDocument5 pagesAre Hypomineralized Primary Molars and Canines Associated With Molar-Incisor HypomineralizationDr Chevyndra100% (1)

- Transport of OxygenDocument13 pagesTransport of OxygenSiti Nurkhaulah JamaluddinNo ratings yet

- Gas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosDocument319 pagesGas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosLuis Eduardo LuceroNo ratings yet

- Fundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebDocument88 pagesFundermax Exterior Technic 2011gb WebarchpavlovicNo ratings yet

- Patent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection SectionsDocument11 pagesPatent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection Sectionsxyz7890No ratings yet

- Elevator Traction Machine CatalogDocument24 pagesElevator Traction Machine CatalogRafif100% (1)

- Stability Calculation of Embedded Bolts For Drop Arm Arrangement For ACC Location Inside TunnelDocument7 pagesStability Calculation of Embedded Bolts For Drop Arm Arrangement For ACC Location Inside TunnelSamwailNo ratings yet

- NDE Procedure - Radiographic TestingDocument43 pagesNDE Procedure - Radiographic TestingJeganeswaranNo ratings yet