Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FQ-Protestant Propaganda Essay

Uploaded by

Amber Morgan FreelandOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FQ-Protestant Propaganda Essay

Uploaded by

Amber Morgan FreelandCopyright:

Available Formats

Morgan-Freeland 1

Amber Morgan Freeland English 534 Dr. Katherine Jacobs December 13, 2010

Protestant Propaganda in Spensers The Faerie Queene When Edmund Spenser first penned The Faerie Queene in 1590, England had already suffered through the worst legacy of the Tudor dynasty the Protestant Reformation and the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation. Thanks to the ever-changing mind of a lustful Henry VIII, centuries of traditional Catholic ideals were suddenly swept away when he declared himself the supreme head of the church so that he could break from his wife of 24 years, Catherine of Aragon, to marry her lady-in-waiting and his pregnant mistress, Anne Boleyn. Just three unhappy years later, heads began to roll and England was in the throes of civil strife as Catholics fought fiercely to retain their role as the one true faith and Protestants revolted against what they saw as false doctrines and ecclesiastical malpractice. After Henry VIIIs death in 1547 his only legitimate son, nineyear old Edward VI (with the help of his advisors), was quick to establish the doctrine of the Church of England thereby officially making the Protestant faith the countrys official religion. His short time as sovereign was followed by his sister, Mary, a fervent Catholic whose five year reign of terror and bloodshed are still remembered today around the

Morgan-Freeland 2

world. But it was Elizabeth, the last of the Tudor dynasty, who was able to reach across both sides and garner an uneasy compromise for the benefit of the people. This, along with her myriad accomplishments during her 60-year reign is just one of the many reasons that authors such as Edmund Spenser have memorialized her in art and literature for the entire world to remember. With all that in mind, one cannot look at Spensers Faerie Queene as simply an allegorical epic homage to his illustrious Gloriana. Instead we must look deeper into the allegory, specifically the characters of Redcrosse, Una, and Duessa, and examine its true purpose to serve as a cleverly disguised piece of Protestant propaganda designed to win over the very soul of England, just as Elizabeth won over its heart. The most obvious way to see how this piece functions as part of Spensers Protestant agenda is to look at how certain characters function within the allegory. Book 1 begins by explaining the legend of the Red Cross Knight (Redcrosse) as a way of highlighting the importance of holiness and morality in ones life, in addition to serving as the symbol for Saint George. As the patron saint of England, George has been venerated throughout Christendom as an example of bravery in defense of the poor and defenseless and of Christian faith (Collins). Georges banner, a red cross on a white background, was adopted for the uniform of the English soldiers during the reign of Richard I and later became part of the Union Jack, Englands official flag (Collins). It is because of this easily recognizable symbol that his representation as the Knight of Holiness and protector of the Virgin can also be seen as a symbol of the Anglican Church upholding the monarchy of Elizabeth I:

Morgan-Freeland 3

But on his breast a bloody Cross he bore The dear remembrance of his dying Lord, For whose sweet sake that glorious badge we wore And dead (as living) ever he adored (Book I, canto i). Because of his battle with the terrible monster, Error, many scholars have also argued that Redcrosse is designed to show Spensers believe in the errors of Catholicism and the truth of Protestantism. While there is certainly evidence for both sides of that argument, it is important to remember that Catholics and Protestants share the same bible and with that the same theme of Christian warfare as procured by Paul the apostle in the book of Ephesians Put on the full armor of God, so that when the day of evil comes, you may be able to stand your ground, and after you have done everything, to stand. Stand firm then, with the belt of truth buckled around your waist, with the breastplate of righteousness in place, and with your feet fitted with the readiness that comes from the gospel of peace. In addition to all this, take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God. (New International Version Eph. 6:13-15). As Erasmus explained in his Handbook of the Militant Christian, Spiritual living requires continual warfare against our vices, our armored enemies and against the devil, world, and flesh, enemies that attack us unceasingly with endless deceptions and secret

Morgan-Freeland 4

contrivances (Litwiller). Because of this commonality between the two faiths, Redcrosse really falls more in-line with John Bunyons Christian or Everyman who simply does what he does because it is his Christian duty to do so. That being said, Spenser clearly adds to this a Protestant emphasis by demonstrating that faith is the most critical part of the Christian suit of armor as opposed to the Catholic emphasis on obedience. As Redcross and the lady Una approach the monstor, Error, Spenser once again alludes to another common theme in the bible, the path of temptation. Una warns him of the dangers of venturing into the cave ahead, this Errours den [where] a monster vile, whom God and man does hate awaits for them in the dark. But Spenser writes that his glistering armor made a little glooming like, much like shade by which he saw the ugly monster plaine. At this, the monster hides from him because she cannot stand the light and does not want to be seen by men. This corresponds directly with biblical metaphors of light as goodness and virtue and darkness as wickedness and temptation. Once the battle begins, Redcrosse quickly realizes that he cannot fight the monster with anger and physical prowess alone, just as Paul wrote in the fourth chapter of Ephesians, In your anger do not sin and do not give the devil a foothold. That is when Una calls out to him to shew what ye bee and add faith until yourforce and be not faint. It is only when Redcrosse relies on his faith that he is able to overcome the evils of temptation (as represented by Error) just as Paul wrote in the second chapter of Ephesians, For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith and this not from yourselves. It is the gift of God, so that no one can boast. This reliance on faith to battle a fierce monster is a

Morgan-Freeland 5

marked difference from older stories, such as Beowulf, where the hero only requires physical strength and belief in their own overly inflated ego to win the battle. Where the anti-Catholic agenda does come into play is no more obvious than when Redcrosse defeats the monster. Once he slays Error, the monster vomits books and papers representative of the Catholic propaganda against the Protestants as distribution of pamphlets that clarified their doctrines and denounced what they saw as heresy were commonplace in that time. Therefore, by killing this monster Redcrosse achieves his first victory over the Roman Catholic Church. It is with the introduction of this character that we are also introduced to the primary female roles of Una and Duessa who represent the Protestant faith and the Catholic faith, respectively. Una is portrayed as pure and virtuous and throughout the book as she provides Redcrosse with the mental/moral guidance he needs to overcome the obstacles ahead of him. One of the most obvious facts that highlight her role in the allegory lies within her name. Unas name derives from the Latin root for one as it suggests that she represents the one true faith. It was, and is, a common Irish name and Spenser no doubt picked it up during his time in exile in Ireland when he was writing The Faerie Queene. But there are other ways that demonstrate that Una symbolizes the one Truth, such as the fact that her appearance is veiled throughout the story except on only two occasions when she is farre from all mens sight in Book I, canto xii. This is because truth is a valuable prize and therefore subject to exploitation as epitomized in the image of Unas virginity. That stubborn forte (I.xii.3.4) must remain closed and

Morgan-Freeland 6

protected from characters such as Sans Loy, which means without law, and Archimago the shape-changing magician. It is only when Redcrosse proves himself a true and worthy knight in book II that she finally appears to him without her veil and cloak. It is then that her true beauty is revealed as the blazing brightnesse of her beauties beame (II.xii.2.18), the alliteration of which suggests how overwhelming her beauty is just as Truth is beautiful to all who deserve to bask in its glory. The uncovering of Truth/Una is done in such a way that one must draw a parallel to the biblical parables that Jesus uses. He says in NIV John 14:6, I am the way, the truth, and the life yet spends most of his time speaking in parables as a way of conveying the truth because it is too profound and too overwhelming on its own. In this same way, Spenser has revealed the truth through Una so as to make the idea easier to grasp for the people of England. Of course all of this was clearly established in the beginning when Una enters the scene just as Jesus did in Jerusalem upon a lowly asse (I.iv) and under a vele that wimpled was full low. And when Una tames the lion, her benevolent truth is once again revealed in nature as suggested by Carol V. Kaske when she says: Unas kinship with animals and nature, while a charming and indeed a mythic touch, remains a mystery. Una can be deceived, at least temporarily byArchimago; she needs to be counseled out of her despair by Arthur; despire being borne of hevenly berth, she has human parents Adam and Eve. These three human touches force us to identify her, at least in her

Morgan-Freeland 7

public role, as a human organization, a church, not truth or wisdom in the abstract. Her liability to deception (though not to sin) illustrates Christs warning that false Christs shall rise, and false prophets, to deceive if it were possible the very elect (Mark 13.22). Thus Spenser elevated the love interest of romance, portrayed a good, redemptive and symbolic damsel [and] added a biblical symmetry by balancing her with a dark damsel [to] symbolize the false church (xix). All of this is in sharp contrast to Duessa whose name immediately suggests a duplicity as it seems to come from the Latin root duo. In Ireland however, the name has connotations to wicked customs, or evil usages. Perhaps because of this in conjunction with her role as the antagonist in The Faerie Queene where Spenser often referred to her malitious use (IV.i.31), the wicked driftes of trayterous desynes (V.ix.42), her mischievous arts (I.ii.34), and her wicked will (I.xii.32) that the name has not been in use in Ireland for nearly two centuries (Smith). Duessa prefers to cloth herself in scarlet red, purfled with gold and pearl of rich assay, in addition to wearing crowns and riches as she rode on her wanton palfrey as opposed to the lowly asse and humble white clothing that Una chooses. Just as Unas attire and mode of transportation are meant to suggest humility and purity, Duessas bring to mind the whore of Babylon: And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet colour, and decked with gold and precious stones and pearls, having a golden cup in her hand full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication (NIV Revelations 17.4). She is presented as a beautiful and tempting woman and Redcrosse is quick to be deceived by her, just as most men are

Morgan-Freeland 8

easily deceived by beautiful and tempting women. But what her clothing really brings to mind is the Catholic churchs tendency to hoard riches and dress their clergy in rich embroidered fabrics and jeweled adornments. Often times the clergy, specifically the cardinals who were also clad in scarlot red, were some of the wealthiest members of English society and this misuse of church funds bred resentment amongst the churchgoers who shouldve been the recipients of good Christian charity. It was this blatant abuse of power that helped give life to the Protestant Reformation in the first place and was one of the first problems that Henry VIII sought to put a stop to (although his reasons were more about refilling his own coffers than concern for his people). This is why Duessa, in all her richly garb, serves as a cover for the greed and corruption of the Catholic church. Redcross finds it difficult to fight off Duessas temptations in his first encounters with her where her doutfull words made that redoubted knight suspect her truth. But once he defeats Sans Foy (which means without faith in Latin), he also defeats the deceit and corruption of the faithless people of the church. But it is not only Duessas clothing that signifies her corruption as we see in her physical description in the scene where Fradubio watches her as she bathes. This scene is fraught with tension as he struggles to see her as her true self while Duessa maintains control by masking her most vital parts (Jeyathurai). The fact that her genitals are hidden by the water lends a murkiness to her power that Fradubio is incapable of fathoming. The unmasking of her body on Unas command reveals a blatantly grotesque description of her breasts, skin, and genitals:

Morgan-Freeland 9

Her dried dugs, lyke bladders lacking wind, Hong down, and filthy matter from them weld; Her wrizled skin as rough, as maple rind, So scabby was, that would haue loathd all womankind (I.viii.47) The visually shocking comparisons between her breasts and a bladder, an excretory organ, help to exemplify that she is filthy through and through and no amount of embellished garb or jewels can possibly hide the disgusting corruption underneath. This is one of Spensers most powerful images that demonstrates the depth of disgust that the Protestants had for the Catholics. But the fact that she is so disgusting underneath also does something else interesting it takes her attractiveness which in turn negates her role as the seductress, and it robs her of her ability to reproduce thereby negating her role as a mother. Even in her allegorical position as the false bride or the Catholic Church, Duessa is denied the ability to birth false knowledge (Jayathurai). Just like the thousand venomous children of the monster Error, Duessas offspring also die prematurely such as her courtship to Redcrosse under the name of Fidessa. Once she has been fully robbed of her role as mother, whore and virgin, Duessa is lopped off from the narrative like a diseased limb in what can be seen almost as a backhanded compliment to Elizabeth who fulfills all three roles (Jaythurai). In the end, readers of The Faerie Queene must be able to see through the outer layer of the allegory and into the deeper layers of politics and religion that reside with the

Morgan-Freeland 10

framework of this allegorical epic. While it can still be predominately viewed as a work designed by a sycophant to praise Queen Elizabeth I, it doesnt take much to see beyond to the political and religious implications buried within the text. Edmund Spenser was clearly a strong supporter of the Protestant Reformation and through his allegory, he hoped to support his queens agenda by subtly highlighting the evils of Catholicism through characters such as Redcrosse, our Everyman/Christian and protector of Una who represents Protestantism as the one True faith from the false seductress of Duessa/Catholicism. In the end, it is only Redcrosses hard-won faith that allows him to discern between the Truth and the lies before him and in that way, Spenser hopes that his readers will also make the same choice for themselves when tempted by the deceptive leaders of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

Morgan-Freeland 11

Works Cited Collins, Michael. "St. George - England's Patron Saint." Britannia: British History and Travel. 2007. Web. 15 Dec. 2010. <http://www.britannia.com/history/stgeorge.html>. Jeyathurai, Dashini Ann. "Exorcizing Female Power in The Faerie Queene." Lethbridge Undergraduate Research Journal. Carleton College. Web. 12 Dec. 2010. <http://www.lurj.org/article.php/vol3n2/duessa.xml>. Kirsch, Johann Peter. "The Reformation." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 13 Dec. 2010 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12700b.htm>. Lewis, C.S., ed. Major British Writers. Enlarged ed. New York: Hartcourt, Brace & World, 1959. 96-103. Print. Litwiller, Sara. "Spiritual Warfare and The Faerie Queene." History Department, Hanover College. Web. 15 Dec. 2010. <http://history.hanover.edu/hhr/00/hhr00_3.html>. Smith, Roland M. "Una and Duessa." PMLA 50.3 (1935): 917-19. Web. 12 Dec. 2010. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/458228>. Spenser, Edmund, and Carol V. Kaske. The Faerie Queene. Indianapolis (Ind.): Hackett, 2006. Print. Sommerville, J. P. "Elizabethan Catholics." History Department, University of Wisconsin. Web. 15 Dec. 2010. <http://history.wisc.edu/sommerville/361/36118.htm>.

You might also like

- Edmund Spenser Faerie QueenDocument6 pagesEdmund Spenser Faerie QueensumiNo ratings yet

- M. A. YadavDocument20 pagesM. A. YadavAnonymous wcKV14BgRNo ratings yet

- Andrew Marvell - To His Coy MistressDocument5 pagesAndrew Marvell - To His Coy MistressBassem KamelNo ratings yet

- 1st Sem EnglishDocument14 pages1st Sem EnglishSoumiki GhoshNo ratings yet

- Examples Figures of Speech and Allusions: THE TIGER by William BlakeDocument4 pagesExamples Figures of Speech and Allusions: THE TIGER by William BlakePatricia BaldonedoNo ratings yet

- CANONIZATIONDocument7 pagesCANONIZATIONNiveditha PalaniNo ratings yet

- Of Revenge by Francis BaconDocument2 pagesOf Revenge by Francis BaconJeyarajan100% (1)

- Faerie Queene Blog 28pDocument28 pagesFaerie Queene Blog 28pEbrahim MahomedNo ratings yet

- Elegy Written in A Country Churchyard SummaryDocument14 pagesElegy Written in A Country Churchyard SummaryashvinNo ratings yet

- Joseph Addison As An EssayistDocument7 pagesJoseph Addison As An EssayistGopi Parganiha100% (1)

- Affliction (I) AnalysisDocument2 pagesAffliction (I) AnalysisSTANLEY RAYENNo ratings yet

- Important Lines of Rape of The LockDocument7 pagesImportant Lines of Rape of The LockElena AiylaNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Topic: Analysis of Last Soliloquy of DR FaustusDocument2 pagesAssignment: Topic: Analysis of Last Soliloquy of DR FaustusIMCB IslamabadNo ratings yet

- On "Lady Lazarus": Eillen M. AirdDocument20 pagesOn "Lady Lazarus": Eillen M. Airdamber19995No ratings yet

- Francis Bacon - of TravelDocument2 pagesFrancis Bacon - of TravelSitesh Sil100% (1)

- Name: Binasree Ghosh: Term PaperDocument7 pagesName: Binasree Ghosh: Term PaperBinasree GhoshNo ratings yet

- The Good Morrow Analysis PDFDocument3 pagesThe Good Morrow Analysis PDFKatie50% (2)

- The Ars PoeticaDocument3 pagesThe Ars PoeticaVikki GaikwadNo ratings yet

- The Faerie Queen (Spenser)Document2 pagesThe Faerie Queen (Spenser)Amy Fowler100% (1)

- Charles Lamb 5Document31 pagesCharles Lamb 5mahiNo ratings yet

- Doctor FaustusDocument5 pagesDoctor FaustusMiguel Angel BravoNo ratings yet

- Digging by Seamus Heaney: Summary and AnalysisDocument1 pageDigging by Seamus Heaney: Summary and AnalysisTasnim Azam MoumiNo ratings yet

- Wife of Bath - Character AnalysisDocument3 pagesWife of Bath - Character AnalysisReal King100% (1)

- Sir Thomas WyattDocument2 pagesSir Thomas WyattAnonymous R99uDjYNo ratings yet

- Doctor Faustus Homework Help QuestionsDocument3 pagesDoctor Faustus Homework Help QuestionsMichelle MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Canonization by John DonneDocument2 pagesThe Canonization by John DonneTaibur Rahaman100% (2)

- Donne Is A Metaphysical PoetDocument6 pagesDonne Is A Metaphysical PoetZeenia azeemNo ratings yet

- The Value of IronyDocument2 pagesThe Value of IronyFuaFua09100% (1)

- Review On Metaphysical PoetryDocument4 pagesReview On Metaphysical PoetryHimanshi SahilNo ratings yet

- NISSIM EZEKIEL PoemsDocument7 pagesNISSIM EZEKIEL PoemsAastha SuranaNo ratings yet

- ComparisonDocument3 pagesComparisonShahid RazwanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Spider and The Bee EpisoDocument5 pagesAnalysis of The Spider and The Bee EpisoP DasNo ratings yet

- Solitary ReaperDocument2 pagesSolitary ReaperKirstenalex100% (2)

- "A Psychoanalytical Study of The Tragic History of DR Faustus" by Christopher Marlow"Document18 pages"A Psychoanalytical Study of The Tragic History of DR Faustus" by Christopher Marlow"Israr KhanNo ratings yet

- The Spectator: BackgroundDocument5 pagesThe Spectator: BackgroundGyanchand ChauhanNo ratings yet

- BaconDocument15 pagesBaconSumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- PoetDocument2 pagesPoetROSERA EDUCATION POINTNo ratings yet

- The Collar - IJSDocument20 pagesThe Collar - IJSIffat Jahan100% (1)

- Importance of Autobiography: George Eliot SDocument4 pagesImportance of Autobiography: George Eliot STasawar AliNo ratings yet

- Trimming Shakespeare's Sonnet 18Document3 pagesTrimming Shakespeare's Sonnet 18Arunava BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- The American Scholar LitChartDocument22 pagesThe American Scholar LitChartmajaA98No ratings yet

- Essays of Francis BaconDocument4 pagesEssays of Francis BaconAradhana YadavNo ratings yet

- 6Document1 page6Kainat Maheen100% (1)

- The Contribution of Charles Lamb As An Essayist To The English LiteratureDocument5 pagesThe Contribution of Charles Lamb As An Essayist To The English LiteratureHimanshuNo ratings yet

- A Valediction of WeepingDocument12 pagesA Valediction of WeepingJeffrey Fernández SalazarNo ratings yet

- Chaucer HumourDocument1 pageChaucer HumouranjumdkNo ratings yet

- A Prayer For My Daughter WB YeatsDocument5 pagesA Prayer For My Daughter WB YeatsTinku ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Troilus and Criseyde: Chaucer, GeoffreyDocument8 pagesTroilus and Criseyde: Chaucer, GeoffreyBrian O'LearyNo ratings yet

- Narrative: The General Prologue To The Canterbury Tales As FrameDocument2 pagesNarrative: The General Prologue To The Canterbury Tales As FrameFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- An Analysis On The Psyche of Richardson's: PamelaDocument5 pagesAn Analysis On The Psyche of Richardson's: PamelaNitu GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast To His Coy Mistress and Sonnet 130Document2 pagesCompare and Contrast To His Coy Mistress and Sonnet 130DeadinDecember100% (1)

- Dr. FaustusDocument10 pagesDr. FaustusEric JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Paradise Lost Essay PDFDocument5 pagesParadise Lost Essay PDFapi-266588958No ratings yet

- Fra Lippo Lippi - Study Guide YR12 LitDocument9 pagesFra Lippo Lippi - Study Guide YR12 LitMrSmithLCNo ratings yet

- Larkin Ambulances1Document4 pagesLarkin Ambulances1Sumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- Assignments Sem.1 (2013-2015) : Examine Dr. Faustus As A Morality Play PDFDocument5 pagesAssignments Sem.1 (2013-2015) : Examine Dr. Faustus As A Morality Play PDFMan PreetNo ratings yet

- Savitri Book 1 Canto 1 Post 4Document3 pagesSavitri Book 1 Canto 1 Post 4api-3740764No ratings yet

- Difference Between Poetry and Philosophy According To Philip SidneyDocument1 pageDifference Between Poetry and Philosophy According To Philip SidneyYasir MasoodNo ratings yet

- Andrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQDocument16 pagesAndrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQRania Al MasoudiNo ratings yet

- Yahoo Tab NotrumpDocument139 pagesYahoo Tab NotrumpJack Forbes100% (1)

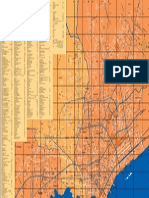

- Map Index: RD - To CE MP AR KDocument1 pageMap Index: RD - To CE MP AR KswaggerboxNo ratings yet

- Power System Planning Lec5aDocument15 pagesPower System Planning Lec5aJoyzaJaneJulaoSemillaNo ratings yet

- Performance Task in Mathematics 10 First Quarter: GuidelinesDocument2 pagesPerformance Task in Mathematics 10 First Quarter: Guidelinesbelle cutiee100% (3)

- Presentation (AJ)Document28 pagesPresentation (AJ)ronaldNo ratings yet

- Ba GastrectomyDocument10 pagesBa GastrectomyHope3750% (2)

- Case Study Diverticulosis PaperDocument12 pagesCase Study Diverticulosis Paperapi-381128376100% (3)

- Cambridge English First Fce From 2015 Reading and Use of English Part 7Document5 pagesCambridge English First Fce From 2015 Reading and Use of English Part 7JunanNo ratings yet

- Caisley, Robert - KissingDocument53 pagesCaisley, Robert - KissingColleen BrutonNo ratings yet

- A Checklist of Winning CrossDocument33 pagesA Checklist of Winning Crossmharmee100% (2)

- CRM Project (Oyo)Document16 pagesCRM Project (Oyo)Meenakshi AgrawalNo ratings yet

- MK Slide PDFDocument26 pagesMK Slide PDFPrabakaran NrdNo ratings yet

- SWOT ANALYSIS - TitleDocument9 pagesSWOT ANALYSIS - TitleAlexis John Altona BetitaNo ratings yet

- 3658 - Implement Load BalancingDocument6 pages3658 - Implement Load BalancingDavid Hung NguyenNo ratings yet

- Mehta 2021Document4 pagesMehta 2021VatokicNo ratings yet

- HSE Matrix PlanDocument5 pagesHSE Matrix Planवात्सल्य कृतार्थ100% (1)

- NAT FOR GRADE 12 (MOCK TEST) Language and CommunicationDocument6 pagesNAT FOR GRADE 12 (MOCK TEST) Language and CommunicationMonica CastroNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in PED 12Document10 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in PED 12alcomfeloNo ratings yet

- Material Concerning Ukrainian-Jewish Relations (1917-1921)Document106 pagesMaterial Concerning Ukrainian-Jewish Relations (1917-1921)lastivka978No ratings yet

- 2018 UPlink NMAT Review Social Science LectureDocument133 pages2018 UPlink NMAT Review Social Science LectureFranchesca LugoNo ratings yet

- Tutor InvoiceDocument13 pagesTutor InvoiceAbdullah NHNo ratings yet

- What Does The Scripture Say - ' - Studies in The Function of Scripture in Early Judaism and Christianity, Volume 1 - The Synoptic GospelsDocument149 pagesWhat Does The Scripture Say - ' - Studies in The Function of Scripture in Early Judaism and Christianity, Volume 1 - The Synoptic GospelsCometa Halley100% (1)

- Disciplines, Intersections and The Future of Communication Research. Journal of Communication 58 603-614iplineDocument12 pagesDisciplines, Intersections and The Future of Communication Research. Journal of Communication 58 603-614iplineErez CohenNo ratings yet

- MNLG 4Document2 pagesMNLG 4Kanchana Venkatesh39% (18)

- Massage Format..Document2 pagesMassage Format..Anahita Malhan100% (2)

- Empirical Formula MgCl2Document3 pagesEmpirical Formula MgCl2yihengcyh100% (1)

- Extraction of Non-Timber Forest Products in The PDFDocument18 pagesExtraction of Non-Timber Forest Products in The PDFRohit Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Marketing Management: by Prabhat Ranjan Choudhury, Sr. Lecturer, B.J.B (A) College, BhubaneswarDocument53 pagesFundamentals of Marketing Management: by Prabhat Ranjan Choudhury, Sr. Lecturer, B.J.B (A) College, Bhubaneswarprabhatrc4235No ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Document20 pagesCambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Balachandran PalaniandyNo ratings yet

- Fail Operational and PassiveDocument1 pageFail Operational and PassiverobsousNo ratings yet