Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Election Cases (Digest)

Uploaded by

Rowneylin SiaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Election Cases (Digest)

Uploaded by

Rowneylin SiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Garchitorena v. Crescini and Imperial Ponente: Johnson, J.

(December 18, 1918) FACTS: It appears from the record that on the 6th day of June, 1916, an election was held in said province for governor, and other provincial and municipal officers. At said election, Andres Garchitorena, Manuel Crescini, Engracio Imperial, and Francisco Botor were candidates for the office of governor. The election was closed. The returns were made by the inspectors of the various municipalities to the provincial board of inspectors which, after an examination of said returns, reached the conclusion that Andres Garchitorena had received 2,468 votes; that Manuel Crescini had received 3,198 votes; that Engracio Imperial had received 1,954 votes and Francisco Botor had received 692 votes. Upon that result the provincial board of inspectors decided that Manuel Crescini had received a plurality of all votes cast, made a proclamation declaring that he had been elected Governor, and issued to him a certificate to that effect. Immediately upon notice of said proclamation, Andres Garchitorena presented a protest against said election, alleging that many frauds and irregularities had been committed in various municipalities of said province, and that he had, in fact, received a majority of all legal votes cast. Two trials were conducted, and the judges (Mina and Paredes) both found in favor of petitioner. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner won the elections. RULING: Yes, petitioner is the winner in the elections. The presumption is that an election is honestly conducted, and the burden of proof to show it otherwise is on the party assailing the return. But when the return is clearly shown to be willfully and corruptly false, the whole of it becomes worthless as proof. When the election has been conducted so irregularly and fraudulently that the true result cannot be ascertained, the whole return must be rejected. It is impossible to make a list of all the frauds which will invalidate an election. Each case must rest upon its own evidence. The record of the frauds and irregularities committed in the said municipalities in which Judges Mina and Paredes annulled the entire vote, not only shows that legal voters were prevented from voting, but in some instances, legal ballots were tampered with and destroyed after they had been cast, to such an extent that no confidence can be placed in the return. The return in no sense discloses the expressed will of the voters. Search has been made in vain for cases in jurisprudence in which the frauds and irregularities committed were more glaring and more atrocious, and in which the real will of the voters were more effectively defeated, than is found in the records in said municipalities in the present case. The statements of fact made by Judges Mina and Paredes relating to said frauds and irregularities are fully sustained by the evidence adduced during the trial of the cause.

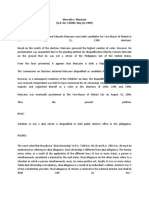

Crisologo Villanueva Y Paredes v. COMELEC Ponente: Teehankee, J. (December 4, 1985) FACTS: Narciso Mendoza, Jr. had filed on January 4, 1980, the last day for filing of certificates of candidacy in the January 30, 1980 local elections, his sworn certificate of candidacy as independent for the office of vice-mayor of the municipality of Dolores, Quezon. But later on the very same day, Mendoza filed an unsworn letter in his own handwriting withdrawing his said certificate of candidacy "for personal reasons." Later on January 25, 1980, petitioner Crisologo Villanueva, upon learning of his companion Mendoza's withdrawal, filed his own sworn "Certificate of Candidacy in substitution" of Mendoza's for the said office of vice mayor as a one-man independent ticket. ... The results showed petitioner to be the clear winner over respondent with a margin of 452 votes. But the Municipal Board of Canvassers disregarded all votes cast in favor of petitioner as stray votes on the basis of the Provincial Election Officer's erroneous opinion that since petitioner's name does not appear in the Comelec's certified list of candidates for that municipality, it could be presumed that his candidacy was not duly approved by the Comelec so that his votes could not be "legally counted. " ... The canvassers accordingly proclaimed respondent Vivencio G. Lirio as the only unopposed candidate and as the duly elected vice mayor of the municipality of Dolores. The COMELEC denied his petition because Mendoza's withdrawal of his certificate is not under oath, as required under Section 27 of the Code; hence it produces no legal effect. For another, said withdrawal was made not after the last day (January 4, 1980) for filing certificates of candidacy, as contemplated under Sec. 28 of the Code, but on that very same day. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner was able to file his certificate of candidacy on time and with the forms prescribed by law and thus, making him the winner of the said elections. RULING: The fact that Mendoza's withdrawal was not sworn is but a technicality which should not be used to frustrate the people's will in favor of petitioner as the substitute candidate. In Guzman us, Board of Canvassers, 48 Phil. 211, clearly applicable, mutatis mutandis this Court held that "(T)he will of the people cannot be frustrated by a technicality that the certificate of candidacy had not been properly sworn to, This legal provision is mandatory and noncompliance therewith before the election would be fatal to the status of the candidate before the electorate, but after the people have expressed their will, the result of the election cannot be defeated by the fact that the candidate has not sworn to his certificate or candidacy."

The Comelec's post-election act of denying petitioner's substitute candidacy certainly does not seem to be in consonance with the substance and spirit of the law. Section 28 of the 1978 Election Code provides for such substitute candidates in case of death. withdrawal or disqualification up to mid-day of the very day of the elections. Mendoza's withdrawal was filed on the last hour of the last day for regular filing of candidacies on January 4, 1980, which he had filed earlier that same day. For all intents and purposes, such withdrawal should therefore be considered as having been made substantially and in truth after the last day, even going by the literal reading of the provision by the Comelec. Nicolas-Lewis v. COMELEC Ponente: Garcia, J. (August 4, 2006) FACTS: Petitioners are successful applicants for recognition of Philippine citizenship under R.A. 9225 which accords to such applicants the right of suffrage, among others. Long before the May 2004 national and local elections, petitioners sought registration and certification as "overseas absentee voter" only to be advised by the Philippine Embassy in the United States that, per a COMELEC letter to the Department of Foreign Affairs dated September 23, 2003, they have yet no right to vote in such elections owing to their lack of the one-year residence requirement prescribed by the Constitution. The same letter, however, urged the different Philippine posts abroad not to discontinue their campaign for voters registration, as the residence restriction adverted to would contextually affect merely certain individuals who would likely be eligible to vote in future elections. A little over a week before the May 10, 2004 elections, or on April 30, 2004, the COMELEC filed a Comment, therein praying for the denial of the petition. As may be expected, petitioners were not able to register let alone vote in said elections. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioners, and others who might have meanwhile retained and/or reacquired Philippine citizenship pursuant to R.A. 9225, may vote as absentee voter under R.A. 9189. RULING: The Court resolves the poser in the affirmative, and thereby accords merit to the petition. As may be noted, there is no provision in the dual citizenship law - R.A. 9225 - requiring "duals" to actually establish residence and physically stay in the Philippines first before they can exercise their right to vote. On the contrary, R.A. 9225, in implicit acknowledgment that duals are most likely non-residents, grants under its Section 5(1) the same right of suffrage as that granted an absentee voter under R.A. 9189. It cannot be overemphasized that R.A. 9189 aims, in essence, to enfranchise as much as possible all overseas Filipinos who, save for the residency requirements exacted of an ordinary voter under ordinary conditions, are qualified to vote.

Also, based from the debates in Congress pertaining to the said law, residence is deemed equivalent to that of domicile, and thus, what the law requires is not physical presence but a mere intent to return to ones country: And the fact that a Filipino may have been physically absent from the Philippines and may be physically a resident of the United States, for example, but has a clear intent to return to the Philippines, will make him qualified as a resident of the Philippines under this law. The members have also stated that the reason Section 2 of Article V was placed immediately after the six-month/one-year residency requirement is to demonstrate unmistakably that Section 2 which authorizes absentee voting is an exception to the six-month/one-year residency requirement. Thus, herein petitioners may exercise their right to vote.

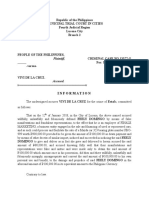

People of the Philippines v. Amadeo Corral Ponente: Abad Santos, J. (January 31, 1936) FACTS: Appellant was charged having voted illegally at the general elections held on June 5, 1934. After due trial, he was convicted on the ground that he had voted while laboring under a legal disqualification. The judgment of conviction was based on section 2642, in connection with section 432. of the Revised Administrative Code. And section 2642 provides: Whoever at any election votes or attempts to vote knowing that he is not entitled so to do, shall be punished by imprisonment for not less than one month nor more than one year and by a fine of not less than one hundred pesos nor more than one thousand pesos, and in all cases by deprivation of the right of suffrage and disqualification from public office for a period of not more than four years. It is undisputed that appellant was sentenced by final judgment of this court promulgated on March 3, 1910, to suffer eight years and one day of presidio mayor. No evidence was presented to show that prior to June 5, 1934, he had been granted a plenary pardon. It is likewise undisputed that at the general elections held on June 5, 1934, the voted in election precinct No. 18 of the municipality of Davao, Province of Davao. ISSUE: Whether or not Corral was entitled to vote during the June 5, 1934 elections. RULING:

Upon the facts established in this case, it seems clear that the appellant was not entitled to vote on June 5 1934, because of section 432 of the Revised Administrative Code which disqualified from voting any person who, since the 13th day of August, 1898, had been sentenced by final judgment to offer not less than eighteen months of imprisonment, such disability not having been removed by plenary pardon. As above stated, the appellant had been sentenced by final judgment to suffer eight years and one day of presidio mayor, and had not been granted a plenary pardon. Counsel for the appellant contend that inasmuch as the latter voted in 1928 his offense had already prescribed, and he could no longer be prosecuted for illegal voting at the general election held on June 5, 1934. This contention is clearly without merit. The disqualification for crime imposed under section 432 of the Revised Administrative Code having once attached on the appellant and not having been subsequently removed by a plenary pardon, continued and rendered it illegal for the appellant to vote at the general elections of 1934.

Occea v. COMELEC PONENTE: Plana, J. (January 31, 1984) FACTS: This petition for prohibition seeks the declaration as unconstitutional of sections 4 and 22 of Batas Pambansa Blg. 222, otherwise known as the Barangay Election Act of 1982, insofar as it prohibits any candidate in the Barangay Election of May 17, 1982 from representing or allowing himself to be represented as a candidate of any political party, political group, political committee...from intervening in the nomination of a candidate in the barangay election or in the filing of his certificate of candidacy, or giving aid or support directly, or indirectly, material or otherwise, favourable to or against his campaign for election. ISSUE: Whether or not the said sections are unconstitutional because it violates the right to form associations and societies for purposes not contrary to law. RULING: It is CONSTITUIONAL. The right to form associations or societies for purposes not contrary to law is neither absolute nor illimitable. It is always subject to the pervasive and dominant police power of the state and may be regulated or curtailed to serve appropriate and important public interests. The right to organize remains intact in Section 4 of the Barangay Elections Act of 1982. Political parties may freely be formed although there is a restriction on their

activities. The ban is merely narrow and not total. It operates only on concerted or group action of political parties. Members of political and kindred organizations, acting individually, may intervene in the barangay election, may intervene in the barangay election. Members of the family of a candidate within the fourth civil degree of consanguinity or affinity as well as personal campaign staff of a candidate can engage in individual or group action to promote the election of their candidate. The provisions of the law which provides that barangay elections must be non-partisan would definitely enhance the objective and impartial discharge of duties for barangay officials to be shielded from political party loyalty. In fine, the ban against the participation of political parties in the barangay election is an appropriate legislative response to the unwholesome effects of partisan bias in the impartial discharge of duties imposed on the barangay and its officials as the basic unit of our political structure.

Rulloda v. COMELEC PONENTE: Ynares-Santiago, J. (January 20, 2003) FACTS: In the barangay elections of July 15, 2002, Romeo N. Rulloda and Remegio L. Placido were the contending candidates for Barangay Chairman of Sto. Tomas, San Jacinto, Pangasinan. On June 22, 2002, Romeo suffered a heart attack and passed away at the Mandaluyong City Medical Center. His widow, petitioner Petronila Betty Rulloda, wrote a letter to the Commission on Elections on June 25, 2002 seeking permission to run as candidate for Barangay Chairman of Sto. Tomas in lieu of her late husband. Petitioners request was supported by the Appeal-Petition containing several signatures of people purporting to be members of the electorate of Barangay Sto. Tomas. Based on the tally of petitioners watchers who were allowed to witness the canvass of votes during the July 15, 2002 elections, petitioner garnered 516 votes while respondent Remegio Placido received 290 votes. Despite this, the Board of Canvassers proclaimed Placido as the Barangay Chairman of Sto. Tomas. A resolution was also released by the COMELEC removing the name of herein petitioner from the name of candidates in accordance with Section 9 of Resolution No. 4801 which states that: There

shall be no substitution of candidates for barangay and sangguniang kabataan officials. ISSUE: Whether or not substitution is allowed in the barangay elections. RULING: Private respondent argues that inasmuch as the barangay election is nonpartisan, there can be no substitution because there is no political party from which to designate the substitute. Such an interpretation, aside from being non sequitur, ignores the purpose of election laws which is to give effect to, rather than frustrate, the will of the voters. It is a solemn duty to uphold the clear and unmistakable mandate of the people. It is well-settled that in case of doubt, political laws must be so construed as to give life and spirit to the popular mandate freely expressed through the ballot. Contrary to respondents claim, the absence of a specific provision governing substitution of candidates in barangay elections cannot be inferred as a prohibition against said substitution. Such a restrictive construction cannot be read into the law where the same is not written. Indeed, there is more reason to allow the substitution of candidates where no political parties are involved than when political considerations or party affiliations reign, a fact that must have been subsumed by law.

Nicacio M. Vivero v. Mateo G. Murillo Ponente: Villareal, J. (January 30, 1929) FACTS: Mateo G. Murillo, the defendant-appellee, was born in the barrio of Paliway, municipality of La Paz, of the Province of Leyte, where he lived with his parents and received his primary education. In order to continue his studies he moved first to Tacloban, Leyte, and later to Calbayog, Samar, and finally to Manila until the year 1927, while acting as private secretary to Senator Veloso. Every year he returns to his native town to spend his vacations which usually lasted from two weeks to one month, remaining alternately in his parents house and in that of his brothers. While he studied he was supported by his parents. With the approach of the general elections of 1925 Senator Veloso assigned him to Burauen, Leyte, for the purpose of campaigning for him, and he became a registered voter these. But before the elections of that year, Murillo returned to Manila in order to continue his law studies. In

December 1926, he went back to La Paz and formally, though verbally, announced his candidacy for the office of municipal president of said municipality at the general elections of 1928. In the same year of 1926 he ordered some wood to be prepared or sawed to be used in the construction of a house for his residence. Later on Murillo returned to Manila and thence wrote to his friends, relatives, and acquaintances, telling them of his candidacy for the office of municipal president of La Paz. For the purposes of said candidacy, Murillo frequently went to his native town. In the month of February, 1927, he brought his family there, leaving them in his parents house when he went back to Manila. In the month of July of the same year he returned to La Paz and lived there with his aforesaid family and later came to Manila. Lastly, in the month of November, 1927, he returned to his said municipality, and did not leave it until the general elections in, June, 1928. On April 4, 1928, Mateo G. Murillo went to Pascual Esplanada, a notary public in the town of the municipality of Burauen, Leyte, to subscribe to a petition under oath which was presented to the municipal treasurer of that municipality to have his name as a voter in Burauen cancelled. On April 14 of the same year, in registering as a voter in the second precinct of La Paz, said defendant Mateo G. Murillo presented a copy of his petition for cancellation to the chairman of the board of inspectors of said municipality, Pedro Tubio. The municipality of La Paz was formely a barrio of the municipality of Burauen, having been organized as an independent municipality in 1918. ISSUE: Whether or not the defendant-appellee, Mateo G. Murillo, had a legal residence in the municipality of La Paz before the general elections of 1928 in order to be eligible to the office of the president of said municipality. RULING: It will be seen that Mateo G. Murillo has always, since his childhood, been a resident of La Paz, not only while it was still a barrio of the Municipality of Burauen, but also after it became an independent municipality, and he did not absent himself therefrom except when studying, first in Tacloban, Leyte, later in Calbayog, Samar, and finally in Manila. By the mere fact of having lived in Tacloban, Leyte, In Calbayog, Samar, and in Manila, as a student, the defendant-appellee did not acquire legal residence in said towns, nor lose his residence in La Paz, because, being single, and supported by his parents while studying, he was dependent on them and their residence was his and it does not appear that he acquired an independent legal residence anywhere else. While it is true that the defendant-appellee registered as a voter in Burauen in the general elections of 1925, yet he did so without any thereto, for it does not appear that he resided in Burauen at any time after the separation of the barrio of La Paz from said municipality and its organization as an independent municipality, nor that he transferred his residence to the former abandoning that of his parents. On the contrary, having continued his studies in Manila, supported by his parents, returning to the latters home during his vacations, it is presumed that he continued to reside with them until the month of November, 1927, when he established his residence in the town of La Paz. Moreover it is sufficiently proven that Mateo G. Murillo had applied in due time and form, for the cancellation of his name as a voter in

the municipality of Burauen, and for his registration as a voter in the municipality of La Paz.

Antonino Tanseco v. Pedro R. Arteche Ponente: Street, J. (September 13, 1932) FACTS: This action of quo warranto was begun on July 10, 1931, by Antonino Tanseco, a voter registered in the list of voters of electoral precinct No. 4 of the Municipality of Catbalogan, in the Province of Samar, for the purpose of having the respondent, Pedro R. Arteche, declared ineligible to the office of provincial governor of Samar. The action was first filed in the Supreme Court

on the last day of filing such, but owing to pressure of work, the SC passed it on to the CFI of Samar. On August 22, 1931, Judge M. L. de la Rosa filed an opinion declaring the election of the respondent to the office of governor of the Province of Samar illegal, for lack of the necessary pre-election residential qualification, and declaring him without right to take possession of the office, with costs in favor of the plaintiff. From this judgment the respondent appealed. ISSUE: Whether or not the respondent, Pedro R. Arteche, had requisite residential qualification at the time he was chosen provincial governor of Samar in the election of June 2, 1931. (The Admin Code requires that for one to be eligible for the position of provincial governor, one must be a bona fide resident of the province for at least prior to the elections.) RULING: Upon these facts we are of the opinion that the trial court committed no error in finding that the respondent had not been bona fide resident of the Province of Samar during the year immediately antedating the election of June 2, 1931. When the statute says that, in order to be eligible to a provincial office, the candidate must have been a bona fide resident in the province for at least one year prior to the election, it implies not only an intention to reside in the place but also personal presence. Bona fide residence under this statute means residence in fact coupled with an intention to make the place a home. (Nuval vs. Guray, 52 Phil., 645, 651.) In the case before us the respondent, by fixing his residence in Manila and engaging in a profession which implies dedication to a life work, effectually severed his home ties and made a new residence in the place of his chosen abode (Respondent was born in Samar, finished his law studies in UST, took the bar examinations, passed it, and decided to make a living as a notary public in Manila because there are more work opportunities in Manila rather than in his hometown.). Looking to the purpose and intent of the law in fixing this qualification, it is evident that the lawmaker intended that persons filling provincial offices should be acquainted with the conditions and needs of the province wherein official service is intended. The question of domicile is admitted question largely of intention, but this intention must be sought in contemporaneous words and acts. The circumstance that the respondent, after removing to Manila and fixing his residence in that place, may have had what is called a floating intention to return to his former domicile upon some indefinite occasion, does not give him the right to claim such former domicile as his residence. It was the fixing of his home in Manila with the intention of remaining there for an indefinite time that severed the respondent's domiciliary relation with his former home.

Raymundo A. Bautista v. COMELEC, Josefina Jareo, Mayor Raymund Apacible, Francisca Rodriguez, Agripina B. Antig, Maria Canovas, and Divina Alcoreza Ponente: Carpio, J. (October 23, 2003)

FACTS: On 10 June 2002, Bautista filed his certificate of candidacy for Punong Barangay in Lumbangan for the 15 July 2002 barangay elections. Election Officer Josefina P. Jareo refused to accept Bautista's certificate of candidacy because he was not a registered voter in Lumbangan. On 11 June 2002, Bautista filed an action for mandamus against Election Officer Jareo with the Regional Trial Court of Batangas, Branch 14. On 1 July 2002, the trial court ordered Election Officer Jareo to accept Bautista's certificate of candidacy and to include his name in the certified list of candidates for Punong Barangay. The trial court ruled that Section 7 (g) of COMELEC Resolution No. 4801 mandates Election Officer Jareo to include the name of Bautista in the certified list of candidates until the COMELEC directs otherwise. Due to this, his name was added in the list of candidates for the election, and the case was forwarded to the COMELEC law department. However, the COMELEC law department was only able to render a decision after Bautista was proclaimed as the winner. COMELEC, then, issued Resolution no. 5404 ordering for the cancellation of the name of Bautista from the list of candidates. Alcoreza, the opponent of Bautista, was declared the Punong Barangay. ISSUE: 1. Whether or not Bautista was not a registered voter of the barangay (and thus, not qualified to run for the position of the Punong Barangay). 2. Whether or not it was proper to declare Alcoreza as the winner. RULING: 1. Bautista was aware (He executed an affidavit recognizing that he was not a registered voter of the said barangay.) when he filed his certificate of candidacy for the office of Punong Barangay that he lacked one of the qualifications - that of being a registered voter in the barangay where he ran for office. He therefore made a misrepresentation of a material fact when he made a false statement in his certificate of candidacy that he was a registered voter in Barangay Lumbangan. An elective office is a public trust. He who aspires for elective office should not make a mockery of the electoral process by falsely representing himself. The importance of a valid certificate of candidacy rests at the very core of the electoral process. Under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, false representation of a material fact in the certificate of candidacy is a ground for the denial or cancellation of the certificate of candidacy. The material misrepresentation contemplated by Section 78 refers to qualifications for elective office. A candidate guilty of misrepresentation may be (1) prevented from running, or (2) if elected, from serving, or (3) prosecuted for violation of the election laws. Invoking salus populi est suprema lex, Bautista argues that the people's choice expressed in the local elections deserves respect. Bautista's invocation of the liberal interpretation of election laws is unavailing. Indeed, the electorate cannot amend or waive the qualifications prescribed by law for elective office. The will of the people as expressed through the ballot cannot cure the vice of ineligibility. The fact that Bautista, a non-registered voter, was elected to the office of Punong Barangay does not erase the fact that he lacks one of the qualifications for Punong Barangay.

2. It is now settled doctrine that the COMELEC cannot proclaim as winner the candidate who obtains the second highest number of votes in case the winning candidate is ineligible or disqualified. Although the COMELEC Law Department recommended to deny due course or to cancel the certificate of candidacy of Bautista on 11 July 2002, the COMELEC en banc failed to act on it before the 15 July 2002 barangay elections. It was only on 23 July 2002 that the COMELEC en banc issued Resolution No. 5404, adopting the recommendation of the COMELEC Law Department and directing the Election Officer to delete Bautista's name from the official list of candidates. Thus, when the electorate voted for Bautista as Punong Barangay on 15 July 2002, it was under the belief that he was qualified. There is no presumption that the electorate agreed to the invalidation of their votes as stray votes in case of Bautista's disqualification. The Court cannot adhere to the theory of respondent Alcoreza that the votes cast in favor of Bautista are stray votes. A subsequent finding by the COMELEC en banc that Bautista is ineligible cannot retroact to the date of elections so as to invalidate the votes cast for him.

Anacleto Luison v. Fidel Garcia Ponente: Bautista Angelo J. (April 25, 1981) FACTS: In the general elections held on November 8, 1955, Anacleto M. Luison and Fidel A. D. Garcia were the only candidates for mayor of Tubay, Agusan. The certificate of candidacy of Luison was filed by the Nacionalista Party of the locality duly signed by the chairman and secretary respectively, while the certificate of candidacy of Garcia was filed by the local branch of the Liberal Party but it was merely signed by one who was a candidate for vice mayor. For this reason, the executive secretary of the Nationalista Party impugned the sufficiency of the certificate of candidacy filed in behalf of Garcia, whereupon the Commission on Elections, after making its own investigation, issued Resolution No. 23 declaring Garcia ineligible to run for the Office. Consequently, the Commission on Elections who immediately implemented it by striking out the name of Garcia from the list of registered candidates. Said secretary also relayed the instruction of the Commission on Elections to the board of inspectors of every precinct and the board of canvassers so that they may be guided accordingly and votes cast for him may not be counted and instead be considered as stray votes. Notwithstanding the adverse ruling of the Commission on Elections, as well as the dismissal of the petition for prohibition sued out by Garcia, the latter continued with his candidacy and the question of his ineligibility became an issue in the campaign. And when the time came for the counting and appreciation of the ballots, the board inspectors, in spite of the adverse ruling of the Commission on Elections, counted all the votes cast for Garcia as valid and credited him with them in the election returns with the result that he garnered 869 votes as against 675 of his opponent Luison. Consequently, the municipal board of canvassers proclaimed Garcia as the mayor elect of Tubay, Agusan. ISSUE: Whether or not the protestee being ineligible and protestant having obtained the next highest number of votes, the latter can be declared entitled to hold the office to be vacated by the former. RULING: The answer is in the negative. As this Court has held, "The general rule is that the fact a plurality or a majority of the votes are cast for an ineligible candidate at a popular election does not entitle the candidate receiving the next highest number of votes to be declared elected. In such case the electors have failed to make a choice and the election is a nullity. In a subsequent case, this Court also said that where the winning candidate has been declared ineligible, the person who obtained second place in the election cannot be declared elected since our law not only does not contain an express provision authorizing such declaration but apparently seems to prohibit it.

Moreover, a protest to disqualify a protestee on the ground of ineligibility is different from that a protest based on frauds and irregularities where it may be shown that protestant was the one really elected for having obtained a plurality of the legal votes. In the first case, while the protestee may be ousted the protestant will not be seated; in the second case, the protestant may assume office after protestee is unseated.

Ellan Marie Cipriano, a minor represented by her father, Rolando Cirpiano v. COMELEC Ponente: Puno, J. (August 10, 2004) FACTS: On June 7, 2002, petitioner filed with the COMELEC her certificate of candidacy as Chairman of the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) for the SK elections held on July 15, 2002. On the date of the elections, July 15, 2002, the COMELEC issued Resolution No. 5363 adopting the recommendation of the Commissions Law Department to deny due course to or cancel the certificates of candidacy of several candidates for the SK elections, including petitioners. The ruling was based on the findings of the Law Department that petitioner and all the other candidates affected by said resolution were not registered voters in the barangay where they intended to run. Petitioner, nonetheless, was allowed to vote in the July 15 SK elections and her name was not deleted from the official list of candidates. After the canvassing of votes, petitioner was proclaimed by the Barangay Board of Canvassers the duly elected SK Chairman of Barangay 38, Pasay City. She took her oath of office on August 14, 2002. On August 19, 2002, petitioner, after learning of Resolution No. 5363, filed with the COMELEC a motion for reconsideration of said resolution. She argued that a certificate of candidacy may only be denied due course or cancelled via an appropriate petition filed by any registered candidate for the same position under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code in relation to Sections 5 and 7 of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 6646. According to petitioner, the report of the Election Officer of Pasay City cannot be considered a petition under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, and the COMELEC cannot, by itself, deny due course to or cancel ones certificate of candidacy. ISSUE: Whether or not the Commission on Elections (COMELEC), on its own, in the exercise of its power to enforce and administer election laws, look into the qualifications of a candidate and cancel his certificate of candidacy on the ground that he lacks the qualifications prescribed by law. HELD: The Commission may NOT, by itself, without the proper proceedings, deny due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy filed in due form. When a candidate files his certificate of candidacy, the COMELEC has a ministerial

duty to receive and acknowledge its receipt. This is provided in Sec. 76 of the Omnibus Election Code, thus: Sec. 76. Ministerial duty of receiving and acknowledging receipt. - The Commission, provincial election supervisor, election registrar or officer designated by the Commission or the board of election inspectors under the succeeding section shall have the ministerial duty to receive and acknowledge receipt of the certificate of candidacy. The Court has ruled that the Commission has no discretion to give or not to give due course to petitioners certificate of candidacy. The duty of the COMELEC to give due course to certificates of candidacy filed in due form is ministerial in character. While the Commission may look into patent defects in the certificates, it may not go into matters not appearing on their face. The question of eligibility or ineligibility of a candidate is thus beyond the usual and proper cognizance of said body. Nonetheless, Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code allows any person to file before the COMELEC a petition to deny due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy on the ground that any material representation therein is false. It states: Sec. 78. Petition to deny due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy. A verified petition seeking to deny due course or to cancel a certificate of candidacy may be filed by any person exclusively on the ground that any material representation contained therein as required under Section 74 hereof is false. The petition may be filed at any time not later than twentyfive days from the time of the filing of the certificate of candidacy and shall be decided, after notice and hearing, not later than fifteen days before the election.

You might also like

- Election Law CasesDocument185 pagesElection Law CasesLara Michelle Sanday BinudinNo ratings yet

- Election Law: By: Dean Hilario Justino F. MoralesDocument19 pagesElection Law: By: Dean Hilario Justino F. MoralesmarkbulloNo ratings yet

- Election LawDocument9 pagesElection LawCha GalangNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Automatic Protection United Feature V MunsingwearDocument2 pagesDoctrine of Automatic Protection United Feature V MunsingwearArah Salas PalacNo ratings yet

- CenPEG Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesCenPEG Vs ComelecJames CullaNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesIbrahim Vs ComelecMichelle Montenegro - Araujo100% (2)

- Hayudini COMELEC Certiorari PetitionDocument2 pagesHayudini COMELEC Certiorari PetitionThea Barte100% (1)

- Ututalum v. COMELECDocument3 pagesUtutalum v. COMELECLance LagmanNo ratings yet

- Election Laws Case DigestDocument12 pagesElection Laws Case DigestNeil MayorNo ratings yet

- Labo Vs Comelec Case DigestDocument3 pagesLabo Vs Comelec Case Digestxsar_xNo ratings yet

- SC rules on prescription of offenses in behest loan casesDocument3 pagesSC rules on prescription of offenses in behest loan casesaldinNo ratings yet

- Ateneo Election Law 2008 General Principles Sources of Philippine Election Law Scope of SuffrageDocument35 pagesAteneo Election Law 2008 General Principles Sources of Philippine Election Law Scope of SuffrageMyooz MyoozNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Disqualification PetitionDocument3 pagesCOMELEC Disqualification PetitionKyla Malapit Garvida100% (2)

- Bar Reviewer On Election LawDocument165 pagesBar Reviewer On Election LawYam LicNo ratings yet

- Villaber Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesVillaber Vs COMELECLeah Marie Sernal100% (3)

- Jaramilla Vs COMELECDocument1 pageJaramilla Vs COMELECRhett GaerlanNo ratings yet

- De Guzman v. SisonDocument2 pagesDe Guzman v. SisonRaymond Roque0% (1)

- Cipriano V COMELECDocument1 pageCipriano V COMELECKimberly MagnoNo ratings yet

- Monsale Vs NicoDocument8 pagesMonsale Vs Nicobraindead_91No ratings yet

- Mauna Vs CSC 232 Scra 388Document8 pagesMauna Vs CSC 232 Scra 388Nurz A TantongNo ratings yet

- Sinsuat V ComelecDocument7 pagesSinsuat V ComelecJermaine Rae Arpia DimayacyacNo ratings yet

- Salic Dumarpa vs. Commission On Elections, G. R. No. 192249, April 02, 2013 (Case Digest)Document1 pageSalic Dumarpa vs. Commission On Elections, G. R. No. 192249, April 02, 2013 (Case Digest)Deanne Mitzi SomolloNo ratings yet

- Fernandez Vs HRET (Case Digest)Document2 pagesFernandez Vs HRET (Case Digest)Cassandra Layson80% (5)

- COMELEC decisions on election casesDocument4 pagesCOMELEC decisions on election casesMarvien M. BarriosNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Ruling on CIBAC Party-List Nominees UpheldDocument7 pagesCOMELEC Ruling on CIBAC Party-List Nominees UpheldJpagNo ratings yet

- Comelec Denies Aklat Petition for Re-Qualification as Party-List GroupDocument2 pagesComelec Denies Aklat Petition for Re-Qualification as Party-List GroupRussel GarciaNo ratings yet

- Sinaca VS Mula and ComelecDocument3 pagesSinaca VS Mula and ComelecBeya AmaroNo ratings yet

- Cawasa Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesCawasa Vs Comelectynapay100% (1)

- Digest of Santos V COMELEC G R No 155618Document1 pageDigest of Santos V COMELEC G R No 155618notaly mae badtingNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds VAT under EO 273Document18 pagesSupreme Court upholds VAT under EO 273Aya AntonioNo ratings yet

- Asistio Vs Aguirre DigestDocument1 pageAsistio Vs Aguirre Digestmrspotter100% (2)

- Ejercito v. ComelecDocument2 pagesEjercito v. ComelecMan2x Salomon75% (4)

- Philippine Election System ExplainedDocument64 pagesPhilippine Election System ExplainedEnteng KabisoteNo ratings yet

- Limbona v. ComelecDocument4 pagesLimbona v. ComelecAlmarius Cadigal100% (1)

- Zapanta v. COMELECDocument3 pagesZapanta v. COMELECnrpostreNo ratings yet

- Labor Cases Illegal RecruitmentDocument13 pagesLabor Cases Illegal Recruitmentpaul100% (1)

- LP Special Lecture ElectDocument15 pagesLP Special Lecture ElectJuvy DimaanoNo ratings yet

- PANGILINAN VS COMELEC COMELEC jurisdiction over pre-proclamation casesDocument3 pagesPANGILINAN VS COMELEC COMELEC jurisdiction over pre-proclamation casesRyan RobertsNo ratings yet

- Jalosjos vs. ComelecDocument3 pagesJalosjos vs. Comelecgianfranco0613100% (1)

- GD ExpressDocument15 pagesGD ExpresslaNo ratings yet

- Banaga v. Comelec DigestDocument3 pagesBanaga v. Comelec DigestJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Tallado v. ComelecDocument2 pagesCase Digest - Tallado v. ComelecZhairah Hassan100% (3)

- LegalCounseling Syllabus AY 2022 2023Document3 pagesLegalCounseling Syllabus AY 2022 2023Nelly Louie CasabuenaNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Digest TopicsDocument17 pagesCivil Procedure Digest TopicsKuthe Ig Toots0% (1)

- Election Strategies Affect Voter BehaviorDocument7 pagesElection Strategies Affect Voter BehaviorVioleta MalanyaonNo ratings yet

- Garchitorena Vs CresciniDocument1 pageGarchitorena Vs Crescinistephcllo100% (2)

- Agustin Vs COMELECDocument6 pagesAgustin Vs COMELECMark Alvin DelizoNo ratings yet

- Election LawDocument12 pagesElection LawJoseph Plazo, Ph.DNo ratings yet

- Banaga v. ComelecDocument2 pagesBanaga v. Comelecjaypee_magaladscribdNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Dicman Vs CarinoDocument2 pagesHeirs of Dicman Vs CarinoJonathan Santos100% (2)

- Locgov 2017Document82 pagesLocgov 2017RhodaNo ratings yet

- Election LawsDocument13 pagesElection LawsBasmuthNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Ruling on Dual Citizenship AffirmedDocument9 pagesCOMELEC Ruling on Dual Citizenship AffirmedRichard BalaisNo ratings yet

- Election Case DigestDocument16 pagesElection Case Digestthesidelinetragedy100% (1)

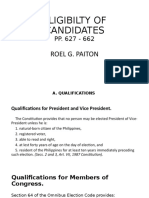

- Admin Law - Eligibility of Candidates PaitonDocument46 pagesAdmin Law - Eligibility of Candidates PaitonAejay Villaruz BariasNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesPimentel V Comelec DigestTrxc Magsino0% (1)

- I. Mariano Ll. Badelles V. Camilo P. Cabili FACTS: Two Election Protests Against The Duly Proclaimed Mayor and Councilors of Iligan City, AfterDocument15 pagesI. Mariano Ll. Badelles V. Camilo P. Cabili FACTS: Two Election Protests Against The Duly Proclaimed Mayor and Councilors of Iligan City, AfterJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Election Law CasesDocument9 pagesElection Law CasesMCg GozoNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Day For Filing of Certificates of Candidacy in The January 30, 1980 Local Elections, His SwornDocument26 pagesSupreme Court: Day For Filing of Certificates of Candidacy in The January 30, 1980 Local Elections, His SwornTtlrpqNo ratings yet

- Election Law Case Digest AY 2021-2022Document9 pagesElection Law Case Digest AY 2021-2022Law School ArchiveNo ratings yet

- AO 168-13 Manual of Operations, Policies & Guidelines For The POLO PDFDocument64 pagesAO 168-13 Manual of Operations, Policies & Guidelines For The POLO PDFRowneylin SiaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On The Imposition of Fines and Penalties PDFDocument4 pagesGuidelines On The Imposition of Fines and Penalties PDFRowneylin SiaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Cases - Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocument56 pagesEthics Cases - Code of Professional ResponsibilityRowneylin Sia97% (39)

- Atty Suspended for Disregarding Court OrdersDocument4 pagesAtty Suspended for Disregarding Court OrdersRowneylin SiaNo ratings yet

- Estes Vs Texas (Case Digest)Document3 pagesEstes Vs Texas (Case Digest)Rowneylin SiaNo ratings yet

- Tyco ScandalDocument5 pagesTyco ScandalJeraldine CerdanNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 Civil DraftingDocument3 pagesMODULE 3 Civil DraftingJaswinNo ratings yet

- Tantuico, Jr. vs. RepublicDocument2 pagesTantuico, Jr. vs. RepublicKathryn Crisostomo PunongbayanNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hoffler-Riddick, 4th Cir. (2007)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Hoffler-Riddick, 4th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff,: InformationDocument3 pagesPlaintiff,: InformationFely DesembranaNo ratings yet

- Forensic Science Textbook Chapter NotesDocument36 pagesForensic Science Textbook Chapter Noteskristyna100% (9)

- Section 156 CRPC Post CognizanceDocument66 pagesSection 156 CRPC Post CognizanceDeepak PanwarNo ratings yet

- USA V Atwell Bodybuilder Arrest Child PornDocument6 pagesUSA V Atwell Bodybuilder Arrest Child PornFile 411No ratings yet

- UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Vs TRAVON DESHAUN-RODERICK MANSKERDocument6 pagesUNITED STATES OF AMERICA Vs TRAVON DESHAUN-RODERICK MANSKERBrandon ChewNo ratings yet

- Delhi HC Bail Application for Domestic Harassment CaseDocument30 pagesDelhi HC Bail Application for Domestic Harassment CaseChetanya Kohli50% (2)

- Equal Protection of The LawDocument72 pagesEqual Protection of The LawLen Vicente - FerrerNo ratings yet

- THE ATTORNEY GENERAL V ADMINISTRATOR GENERALDocument16 pagesTHE ATTORNEY GENERAL V ADMINISTRATOR GENERALStan SeanNo ratings yet

- Judgment: Secretary of The State Capture Commission V JG ZumaDocument44 pagesJudgment: Secretary of The State Capture Commission V JG ZumaMail and GuardianNo ratings yet

- 2004 LawSuit (All) 1386Document16 pages2004 LawSuit (All) 1386Devanshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure - Case 19 Alcaraz V PeopleDocument1 pageSearch and Seizure - Case 19 Alcaraz V PeopleChristopher Jan DotimasNo ratings yet

- USA v. Moshe PoratDocument30 pagesUSA v. Moshe PoratKennedy RoseNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 197818. February 25, 2015. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ALLAN DIAZ y ROXAS, Accused-AppellantDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 197818. February 25, 2015. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ALLAN DIAZ y ROXAS, Accused-AppellantRuby Patricia MaronillaNo ratings yet

- Massachusetts Child Abuse Reporting RequirementsDocument5 pagesMassachusetts Child Abuse Reporting RequirementsBeverly TranNo ratings yet

- World Wide Web V PeopleDocument3 pagesWorld Wide Web V PeopleASGarcia24No ratings yet

- Conditional Guilty Plea For Consent JudgmentDocument12 pagesConditional Guilty Plea For Consent JudgmentForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- S I (D) U S L S, P: Ymbiosis Nternational Eemed Niversity Ymbiosis AW Chool UNEDocument3 pagesS I (D) U S L S, P: Ymbiosis Nternational Eemed Niversity Ymbiosis AW Chool UNEShreya SinghNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Rules Amendments Simplify LitigationDocument6 pagesCivil Procedure Rules Amendments Simplify LitigationLlb DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Narciso Gutierrez VsDocument1 pageNarciso Gutierrez VsFranz BiagNo ratings yet

- 1571208761-C P CDocument88 pages1571208761-C P ClaxmiNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Exam Questions Cover Statute of Limitations, Perjury, BriberyDocument10 pagesLegal Ethics Exam Questions Cover Statute of Limitations, Perjury, BriberyFrances Ann TevesNo ratings yet

- BrigandageDocument6 pagesBrigandageAmado Vallejo IIINo ratings yet

- Crime and Consequences in The Stranger and The Brothers KaramazovDocument13 pagesCrime and Consequences in The Stranger and The Brothers KaramazovDaniela Garza0% (1)

- Admission: Section 17 To 31Document12 pagesAdmission: Section 17 To 31gaurav singhNo ratings yet

- Elements of malversationDocument2 pagesElements of malversationWreigh ParisNo ratings yet

- Duran & Lim For Respondent. Attorney-General Jaranilla and Provincial Fiscal Jose For The GovernmentDocument46 pagesDuran & Lim For Respondent. Attorney-General Jaranilla and Provincial Fiscal Jose For The GovernmentYanilyAnnVldzNo ratings yet