Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nzier RWC

Uploaded by

Stewart HaynesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nzier RWC

Uploaded by

Stewart HaynesCopyright:

Available Formats

40/2012

Independent, authoritative analysis

Insight

The host with the most?

Rethinking the costs and benefits of hosting major events

Hosting large events like the Rugby World Cup are expensive undertakings. That makes value-for-money evaluation critical. But most impact event analysis doesnt stack up, missing displacement effects. It means benefits are often far smaller than people think. Most event analysis misses visitor displacement

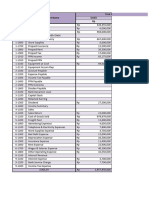

Major international events attract extra visitors during the event. But events tend to suck in visitors from before and after the event, when people coincide the timing of visits with the event. This displacement effect means the net number of visitors an event generates is much lower than the visitors to the event. The Rugby World Cup 2011 is a good example. We estimate there was little overall boost to visitor arrivals because there were fewer visitors before and after the 133,000 1 international visitors that came to New Zealand for the tournament (see figure 1).

Figure 1 People shift the timing of visits to coincide with events, displacing visitor arrivals

Seasonally adjusted and trend visitors arrivals

Source: Statistics New Zealand

Professor Dickson (Auckland University of Technology) suggests net new arrivals could be as few as 25,000.

NZIER Insights are short notes designed to stimulate discussion on topical issues or to illustrate frameworks available for analysing economic problems. They are produced by NZIER as part of its self-funded Public Good research programme. NZIER is an independent non-profit organisation, founded in 1958, that uses applied economic analysis to provide business and policy advice to clients in the public and private sectors. While NZIER will use all reasonable endeavours in undertaking contract research and producing reports to ensure the information is as accurate as practicable, the Institute, its contributors, employees, and Board shall not be liable (whether in contract, tort (including negligence), equity or on any other basis) for any loss or damage sustained by any person relying on such work whatever the cause of such loss or damage.

Independent, authoritative analysis

Most regional event analysis also misses expenditure displacement

Crucially, domestic tourism is displaced expenditure that would occur elsewhere in the economy. This significantly reduces the overall benefit from the events. Simply put, major domestic events do not make New Zealanders any wealthier. Increased spending at the major event is mostly offset by reduced spending elsewhere. This might be reductions in other holidays, spending on take-aways and eating out, or spending on household items such as TVs. Most event analyses use multipliers to capture second rounds of spending from the profits and wages captured by local events. But the multipliers used to capture second round spending also need to be applied to the reduction in spending that cannot now occur elsewhere in the economy. The displaced expenditure argument makes for a clear policy recommendation: if international events bring extra money into New Zealand they have net benefits to New Zealand. Regional events are more likely to only reallocate spending across regions. They are likely to benefit the region, but at a national level lets be clear little additional income is generated by these events.

Infrastructure expenditure also must be funded

Large international events, like the Rugby World Cup and the Olympics, leave the host region with better facilities, and sometimes upgraded transport links. But infrastructure is expensive, and the costs are largely borne by local residents once tourism displacement is considered. In addition, the costs of major events typically blow out. Research by the Sad Business School at Oxford University shows 2 that every Olympics since 1960 averaged a cost overrun of 179%. Event analysis needs to consider who pays for the infrastructure, and any likely cost overruns. For the large costs to stack up economically, the infrastructure needs to deliver lasting dividends long after the major event is finished. This means sound planning so that the business case for the infrastructure stands up over the long term. The East London development for the London 2012 Olympics appears sound, investing in an area that was otherwise run-down; similarly developments of the Barcelona waterfront for the 1992 Olympics have left lasting benefits to the city. The event analysis needs to consider the usage of infrastructure long after the event has finished.

A better approach to evaluating tourism events

There are a range of implications for evaluating the economic benefits of major events: 1. The national benefits of any major event will largely be dependent on increases in international tourism. The numbers used in evaluations must consider displacement effects. 2. The perspective of the evaluation matters. A major event might have net benefits for a region, but be welfare-reducing for the country as a whole. 3. The analysis must be consider who pays for the infrastructure. When there are few new tourists, the costs are likely to fall on the local region. 4. The analysis is complex, with different impacts across industries and regions. The economywide impact of a major event depends on how tourism crowds out other sectors. This depends on capital and labour constraints, and the state of the economy (Dwyer et al 2005). These points are the reason why NZIER has made Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) modelling the tool of choice to evaluate events. The Australian Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research

http://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/newsandevents/releases/Pages/LondonOlympicsoverbudget.aspx 2

NZIER Insight Rethinking the costs and benefits of hosting major events

Independent, authoritative analysis

Centre (STCRC) support that view. CGE modelling captures displaced expenditure across industries and regions, and who ends up paying for any infrastructure costs. An alternative approach is to use the input-output (I-O) or multiplier models. But these models do not include key economic constraints, price changes or displacement impacts and therefore overestimate the benefits of major events. Dwyer et al (2005) find I-O model estimates are 180% to 500% higher than CGE estimates.

Be clear about the impacts of major events

Major events that can bring new tourists can generate positive benefits for a region. However, these events are costly undertakings that need to be evaluated using analysis that holds up to scrutiny. Simple multiplier analysis that overstates short-run benefits by ignoring displaced visitors and displaced expenditure simply doesnt cut it.

References

Dwyer, L, Forsyth, P and Spurr, R. (2005). Estimating the impacts of Special Events on the Economy. Journal of Travel Research, Vol 43, pp 351-359. Dwyer, L and Spurr, R. (2010). Tourism Economics Summary. STCRC for Economics and Policy. MacFarlane, I and Jago, L. (2009). The role of brand equity in helping to evaluate the contribution of major events. STCRC for Economics and Policy. Oxford Economics (2012). The Economic Impact of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

This Insight was written by Chris Schilling, Senior Economist at NZIER, October 2012. For further information please contact Chris on chris.schilling@nzier.org.nz

NZIER | (04) 472 1880 | econ@nzier.org.nz | PO Box 3479 Wellington

NZIER Insight Rethinking the costs and benefits of hosting major events

You might also like

- CIR V Central LuzonDocument2 pagesCIR V Central LuzonAgnes FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Ferrari Company Presentation: Strategic AnalysisDocument25 pagesFerrari Company Presentation: Strategic AnalysisEmanuele BoreanNo ratings yet

- RESA First Pre-Board ExamDocument14 pagesRESA First Pre-Board ExamMark LagsNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal: Financial Analysis of Hospitality Sector in UKDocument13 pagesResearch Proposal: Financial Analysis of Hospitality Sector in UKRama Kedia100% (1)

- CPA Review School of the Philippines Final Pre-board ExaminationDocument67 pagesCPA Review School of the Philippines Final Pre-board ExaminationCykee Hanna Quizo Lumongsod100% (1)

- BA 99.1 Rodriguez LE 1 SamplexDocument6 pagesBA 99.1 Rodriguez LE 1 SamplexYsabella Beatriz SamsonNo ratings yet

- Case 22 Victoria Chemicals A DONEDocument14 pagesCase 22 Victoria Chemicals A DONEJordan Green100% (5)

- The Economic Impacts of EcotourismDocument4 pagesThe Economic Impacts of EcotourismShoaib MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Tourism Economic Impact GuideDocument32 pagesTourism Economic Impact Guidehaffa100% (1)

- MGBBT0FYPDocument5 pagesMGBBT0FYPnivedita singhNo ratings yet

- Tourism's Economic ImpactsDocument17 pagesTourism's Economic ImpactsmeeeeehhhNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Tourism After COVID-19: Insights and Recommendations for Asia and the PacificFrom EverandSustainable Tourism After COVID-19: Insights and Recommendations for Asia and the PacificNo ratings yet

- (已压缩)TOUR1004 Week 9 Economic Analysis for EventsDocument36 pages(已压缩)TOUR1004 Week 9 Economic Analysis for EventsWajeeha NafeesNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Major Events and Avoiding The Mercantialist FallacyDocument12 pagesEvaluating Major Events and Avoiding The Mercantialist FallacyNiclas HellNo ratings yet

- Economic Impacts of Olympic Games - 09.07.09Document11 pagesEconomic Impacts of Olympic Games - 09.07.09Cristina TalpăuNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact of The Sydney Olympic Games: January 1998Document28 pagesEconomic Impact of The Sydney Olympic Games: January 1998SashaFierce Los A&ANo ratings yet

- Economic Impact StudyDocument10 pagesEconomic Impact StudyMaddy RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Test 1Document3 pagesTest 1Jhaz OcampoNo ratings yet

- Airlines Industry Final Submission RevisedDocument10 pagesAirlines Industry Final Submission RevisedRonnie BuctolanNo ratings yet

- Business TourismDocument8 pagesBusiness TourismSipos HajniNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact Study of a Northern California Convention CenterDocument7 pagesEconomic Impact Study of a Northern California Convention CenterJosielyn ArrezaNo ratings yet

- 96f4f Example 1Document8 pages96f4f Example 1Kanan AhmadovNo ratings yet

- Asian Incentive Events NSW PDFDocument28 pagesAsian Incentive Events NSW PDFFebrian WardaniNo ratings yet

- Dissertation GDPDocument7 pagesDissertation GDPThesisPapersForSaleSingapore100% (1)

- Mega Events Economic Impact FIFA 2002 30.10.Document9 pagesMega Events Economic Impact FIFA 2002 30.10.LukaNo ratings yet

- Mice4 PPRDocument32 pagesMice4 PPRJohn Angelo SibayanNo ratings yet

- Forecast 2012 Issue 2Document34 pagesForecast 2012 Issue 2Ana Maria ToiaNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact Ex 1Document18 pagesEconomic Impact Ex 1clairecorfuNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Economic Impacts of Events - A Computable General Equilibrium ApproachDocument8 pagesAssessing The Economic Impacts of Events - A Computable General Equilibrium ApproachpadsockNo ratings yet

- EMT201 TMA01 Yhwong010 WongYongHawDocument6 pagesEMT201 TMA01 Yhwong010 WongYongHawYong HawNo ratings yet

- KFC YUM Center Report FinalDocument24 pagesKFC YUM Center Report FinalHouseLannister1No ratings yet

- Aviation Management at Emirates AirlinesDocument12 pagesAviation Management at Emirates AirlinesYamNo ratings yet

- l8 Socioeconomic Evaluation Lecture NotesDocument52 pagesl8 Socioeconomic Evaluation Lecture NotessindywangNo ratings yet

- Employment: Tourism'S Economic ImpactDocument11 pagesEmployment: Tourism'S Economic ImpactmeeeeehhhNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment Thesis TopicDocument4 pagesForeign Direct Investment Thesis TopicCustomPaperWritingServicesUK100% (1)

- Unit 1 - Impacts of TourismDocument36 pagesUnit 1 - Impacts of TourismroshanehkNo ratings yet

- Domestic Tourism - The Backbone of The IndustryDocument15 pagesDomestic Tourism - The Backbone of The IndustryZachary Thomas TanNo ratings yet

- Economic Impacts of Hosting the Olympics: A State ComparisonDocument97 pagesEconomic Impacts of Hosting the Olympics: A State Comparisonvembos100% (1)

- Chapter 005 PMDocument5 pagesChapter 005 PMHayelom Tadesse GebreNo ratings yet

- CSSI ReportDocument44 pagesCSSI ReportHimanshu RaiNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact of 2012 OlympicsDocument72 pagesEconomic Impact of 2012 OlympicsAmit JainNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five Globalization and Society: ObjectivesDocument14 pagesChapter Five Globalization and Society: ObjectivesEudora MaNo ratings yet

- Use of Tourism Statistics in Macro-Economic & Business PlanningDocument38 pagesUse of Tourism Statistics in Macro-Economic & Business PlanningEfraim EspinosaNo ratings yet

- 2.8 Socioeconomic and cultural impact assessment exampleDocument4 pages2.8 Socioeconomic and cultural impact assessment exampleMusaab MohamedNo ratings yet

- New Zealand Tourism Forecasting Methodology 2006: September 2006Document49 pagesNew Zealand Tourism Forecasting Methodology 2006: September 2006john9614No ratings yet

- DNC Economic Impact StudyDocument23 pagesDNC Economic Impact StudyPrabhat KumarNo ratings yet

- Thesis Fdi Economic GrowthDocument8 pagesThesis Fdi Economic Growthmarybrownarlington100% (2)

- Annals of Tourism Research: Onil Banerjee, Martin Cicowiez, Jamie CottaDocument24 pagesAnnals of Tourism Research: Onil Banerjee, Martin Cicowiez, Jamie Cottashitahun workuNo ratings yet

- Local Economy: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument12 pagesLocal Economy: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationMyunghee LeeNo ratings yet

- Measuring the Impact of Mega-Sport Events on Tourist ArrivalsDocument7 pagesMeasuring the Impact of Mega-Sport Events on Tourist ArrivalsAyman LAMRHANINo ratings yet

- Topic 1 ContinuationDocument6 pagesTopic 1 ContinuationJimmy AchasNo ratings yet

- Lesson4 632501919024592Document15 pagesLesson4 632501919024592HazeL Joy DegulacionNo ratings yet

- A Review of Economic Impact Analysis For Tourism and Its Implications For MacaoDocument15 pagesA Review of Economic Impact Analysis For Tourism and Its Implications For MacaoSriyantha FernandoNo ratings yet

- Whitepaper Web Final NewDocument16 pagesWhitepaper Web Final NewjantjekutNo ratings yet

- IJSBAR Financial Statement AuditDocument10 pagesIJSBAR Financial Statement AuditAkademski ServisNo ratings yet

- EMSI CCNY Economic Impact ReportDocument105 pagesEMSI CCNY Economic Impact ReportCCNY CommunicationsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 &7Document6 pagesChapter 6 &7demeketeme2013No ratings yet

- 22final Papermaria BorgaDocument30 pages22final Papermaria BorgabrakatakbrokotokNo ratings yet

- BarreraDocument27 pagesBarrerajustincasipe9No ratings yet

- Three Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsDocument25 pagesThree Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsRodrick WilbroadNo ratings yet

- Agricultural EconomicsDocument45 pagesAgricultural EconomicsMilkessa SeyoumNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Impact on Insight Vacations Capstone ProjectDocument13 pagesCOVID-19 Impact on Insight Vacations Capstone ProjectAakash ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Investment Plan ExampleDocument13 pagesInvestment Plan ExampleSan Thida SweNo ratings yet

- Use of Tourism Statistics in Macroeconomic and Business PlanningDocument38 pagesUse of Tourism Statistics in Macroeconomic and Business PlanningSarahCawasNo ratings yet

- Lab AssignmentDocument16 pagesLab Assignmentakansha mehtaNo ratings yet

- The Economic, Social, Environmental, and Psychological Impacts of Tourism DevelopmentFrom EverandThe Economic, Social, Environmental, and Psychological Impacts of Tourism DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Open Letter To Labour & The Greens PDFDocument2 pagesOpen Letter To Labour & The Greens PDFStewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Qualmark Apartment CriteriaDocument27 pagesQualmark Apartment CriteriaStewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Jasons Travel Media Financial Forecast To March 2013 PDFDocument2 pagesJasons Travel Media Financial Forecast To March 2013 PDFStewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- The Digital UniverseDocument17 pagesThe Digital UniverseStewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Qualmark NZ Motel CriteriaDocument25 pagesQualmark NZ Motel CriteriaStewart Haynes100% (1)

- Alleged Discrimination of Sole Sex Worker at MotelDocument18 pagesAlleged Discrimination of Sole Sex Worker at MotelStewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- TNZ Visitor Experience Monitor - 2011-12Document45 pagesTNZ Visitor Experience Monitor - 2011-12Stewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Mood of The New Zealand Traveller February 2010Document4 pagesMood of The New Zealand Traveller February 2010Stewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Global Travel Trends 2011Document56 pagesGlobal Travel Trends 2011Stewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- New Direction For Qualmark 2011Document43 pagesNew Direction For Qualmark 2011Stewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- South Africa Draft Tourism Bill 2011Document40 pagesSouth Africa Draft Tourism Bill 2011Stewart HaynesNo ratings yet

- Statement of Cash Flows Ca5106Document57 pagesStatement of Cash Flows Ca5106Bon juric Jr.No ratings yet

- WEEK 4 Finance and Strategic Management UU MBA 710 ZM 22033Document10 pagesWEEK 4 Finance and Strategic Management UU MBA 710 ZM 22033Obiamaka UzoechinaNo ratings yet

- Shareholder's EquityDocument10 pagesShareholder's EquityNicole Gole CruzNo ratings yet

- Correcting Entries For PPEDocument8 pagesCorrecting Entries For PPEhazel alvarezNo ratings yet

- Practice Exam Chapters 1-5 Adjusting EntriesDocument7 pagesPractice Exam Chapters 1-5 Adjusting Entriesswoop9No ratings yet

- Damodaran - Financial Services ValuationDocument4 pagesDamodaran - Financial Services ValuationBogdan TudoseNo ratings yet

- Malta TINDocument4 pagesMalta TINMelvin ScorfnaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Notes Full CompleteDocument17 pagesChapter 3 Notes Full CompleteTakreem AliNo ratings yet

- Maf 635 Chapter 3Document39 pagesMaf 635 Chapter 3anisaa_safriNo ratings yet

- Dillard - R - WK #11 Assignment Intermediate Accounting 2Document11 pagesDillard - R - WK #11 Assignment Intermediate Accounting 2Rdillard12No ratings yet

- Paystub TjmaxxDocument1 pagePaystub Tjmaxxyishii258000No ratings yet

- PartnershipDocument330 pagesPartnershipAbby Sta Ana100% (2)

- Micro Economics Study GuideDocument74 pagesMicro Economics Study GuideAdam RNo ratings yet

- Siklus Akuntansi Pada PT Adi JayaDocument11 pagesSiklus Akuntansi Pada PT Adi Jayafitrianura04No ratings yet

- MusharkaDocument33 pagesMusharkaDaniyal100% (1)

- BudgetingDocument2 pagesBudgetingKalsia RobertNo ratings yet

- Lumentum Company OverviewDocument19 pagesLumentum Company OverviewEduardoNo ratings yet

- Ep 1130 Assignment 2Document4 pagesEp 1130 Assignment 2rajelearningNo ratings yet

- Ch27 Test Bank 4-5-10Document18 pagesCh27 Test Bank 4-5-10KarenNo ratings yet

- Balakrishnan 2011Document67 pagesBalakrishnan 2011novie endi nugrohoNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle Prob 14Document24 pagesAccounting Cycle Prob 14Mc Clent CervantesNo ratings yet

- Revenue Procedure 2014-11Document10 pagesRevenue Procedure 2014-11Leonard E Sienko JrNo ratings yet

- RR No. 25-2020Document2 pagesRR No. 25-2020Kram Ynothna BulahanNo ratings yet