Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Massimo Scaligero - The Tantra and The Spirit of West (1955)

Uploaded by

Piero CammerinesiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Massimo Scaligero - The Tantra and The Spirit of West (1955)

Uploaded by

Piero CammerinesiCopyright:

Available Formats

TI{8, TANTRA AND TI{E, -W.

E,ST SPIRIT OF THE,

What need is there for the Tantra when we have the Veda? In reply to this enquiry the commentator of the Tantra will tell you that they meet the needs of the men of our times, the need of the soul of that modern man who seems to have cut himself off from traditions and revelations and feels himself to be a selfreliant inclividuality, a free being: we

Westernr:rs would express

sciousness

r>.

it as

<<

self-con-

We have indeed the impre,ssion that the Tantra books speak above all to rhe Faustian, anti-mystical type of the new man, as Goethe conceived him; who wishes to base his inner experiences cn the granitic foundations of reality, courage, {reedom from prejudices. Even the love of the child {or the Mother means nuthing if it be not an act of will, the donation of something organic one really possesses. Such devotion is, indeed, an aspect of power. How can one give something one has not got? These considerations lvere aroused in us on seeing the beautiful new edition of the Tantra Tattua of Shriyukta Shiva Chandra Vidyirnava BhattachAryya Mahodaya, published under the title of Principles ,f Tarutra (Publishers: Ganesh & Co, Madras, L952, pp. 1200). As is

in Arthur Avalon's introdur:tion. To him is due the credit nf having, bv his subsequent essays and by the publication of the texts, 'World to hecome enalrled the Western acquainted with the Tantra doctrines. The central theme of the work is that of the Sakti, that is to say, the theme of the prirnordial cosmic power. What is Saftri? The usual idea man {orms of power is of something related to his mode of being and o{ knowing; but this mode, in so far as it is not possessed in its full value, cannot be the measure of polver per se. It is evident that the Tantric system in which all the metaphysical con' ceptions of India converge and interpenetrate, frorn the antique Yedic ritualism to the recent Visnuite mysticism, brings a new element into the world of tradition: the awareness of the changes that have occurred in the inner mind of nran, in his Kali-yuga, and the intuition o.[ a new type of spiritual actiyity. It would seern that the Tantras possessed that knowledge (which in the West lies at the foundation oI -od".., philosophy) of the fall

known, the Tantra-tattua, the systematic presentation of the Tantra-sdsfro, was pub' ago, edited lished forty years 'Woodroffe) by Arthur who had as Avalon (Sir John

collaborators Shri Jnanendralal Maiumdir and Shri BaradA KAnta Majumdir. This second edition contains in one volume the two then puhlished and is still the basic text required for an understanding of lhe 7'antra-shastra, thanks partly to the clear summary contained

of the ancient metaphysical conceptions accordirrg to which man is guided by the gods, hy revelations, inspirations. The Gods now leave man alone; he must stand by himself I he must fulfil in himself and by his own unaided efforts, the nature with which he has been endowed from the beginning. Those who wish to turn back, follow << the path of the dead n, for they only unbury in themselves former states of rronsciousness, beyond which malf: rnust now pass if he is to be himself ; it is the way of liberation. The Gods expect man to travel along that path: he is not to return to a state of dependence and passive remissive-

29L

ness? jrrstilierl only in anoient tirnes when rnan was not yet really born as a personality (Siua), but lay immersed in the hosom of the Mother (Sakti). Gradually, as time passed hy, accompanied hy r:orresponding revelations (the tratlitional Yoga), man acrluired an indepentlent personality; hut he paid for this individuality by the ]o,ss of the ancient states of transcendent

consciousness. Man's experient,e hecotnes rnore and more of this earth; it is rhe Kali yur:a, the darh night that precedes dawn. The ancient Mother now leaves man alone in the solitude of sensorial experience, for he rnust now face the responsibilities of freedom. Antl it is just for this that the Mother must now be fountl again in the material world, the world of sensation, in the physical body. Nor r:an this rediscovery be made any longer as a gift from the gods I it must be a free action, a personal initiative taken hy man, something he may decide to do, hut that he mav alsrr refuse. This is the path of freedom; hut it is also the way for the rediscovery of the Mother in conformity with a new Yoga, which remains an impenetrable mystery for those who are immersetl in that traditionalism in which Tradition no longer flows. If it does not flow it is because tradition may not lte confined once and for all in rhis or lhat systemI it does not allow itself to be fixed in ritualistic forms, in human hahits and custom,s, for its perennial and unchangeable character lies in its perpetual transmutations. To find once more the Mother, the primaeval

today is immersed in a dreamless sleep: this is the taslr to which the sat-cakra-sddhana points: the principle of consciousness itself , of Siuc, rrrust be reached in its abode, the sahasrdracakra, whenee it will draw strength to tlescend to the mitlildhdra-caltra, and join with the principle of creative power, the Shakti,, slurnbering there in the form of the serpent, Kundalini. The means for performing such a task is that which, in Western terminology, would be described as <<ah,solute immanence>. All forms of transcendency are now ahstractions for man lvho has no longer the direct perception of the Divine. That awareness from which the

start is made can not be replaced by intellectual postulates which make no substantial change in the far:tual condition of human nature. The awareness man already has, his physical

constitution, his lrody, are the positive points fronr which the start is made. It is a question of reconquering those modes of being in their essence. If the foundations of the world are really in the Divine, then the Divine will he found there as a positive essence. Such is the premise to the methotl taught lry rhe Tantra. Their theory develops in conformity with a doctrine of knowledge which does not seek confirmation in itself hut in the method it im' plies. It is not, therefore, a tluestion of turn' ing back, of seeking for the corpse in oneself which is what is being done tinawaredly by - West with psychoanalysis, analytical the

psyrholngy, of which such outstanding

instilling fictitious life into that which

personalities as Shri Aurobindo and Ramana Maharshi have spoken with justified severity -- it is a cluestion of going forward, not of

is

deacl by recourse to means which are themselves connected with dead things, but of resuscitating it, taking possession of the essence of one's own being, transmuting oneself . in so According to the Tarutra << being > far as it is an exterior physical or superphysiopposes thought in so far as t:al reality - is opposed to being, that is to thought itself say in so far as thought, una\Mare of the very act by which it consecrates life, lives as an abstract function, detached from the central focus of the individual. The Tantra thus conceive the reality of being, not as proceeding from a principle re' ferahle to that reality, but as arising from the relations by which the Ego can appropriate it. What distinguishes the several forms of experience to which this gives rise, is the degree of union existing betwen Siua and Sdkti, that is to say the degree in which the divine force becomes action. Thus the purely intellectual or tlevotional methods of the previous schools are eliminated, making room for the conquest of the most deep seated centre of personality, which is the starting point along rhe path leading to the possibility of dominating li{e and physical reality. The exterior order of things is in itself power, and the polver vested in a thing does not depend on intellectual recognition, i. e. reflected thought. flere, therefore, MAyA is not a value in itself but one of the ways in which Sa/cri presents itself ; it is, therefore, Mdyd-Sakti. The jiaa may even allow himself to conceive the world as a play of illusions, a dream, a phantom; but this phantom will always be able to force

power towards which human

conscience

292

itself on hirn as llrute necessity, whatever his nrental position may be. The 'Inntra, on the other hand, seek to acquire sure knowletlge of principles from their corresponding results. The prnof of power is in its action. The Divine Power itself , the Mother, becomes action in all its forrns of manifestation, down to what may appear to be Maya I hut at each degree, as knowledge and action are one ir position of absolute immanence which in some way rerninds one by analogy of the 1)erum et facutm cont)erturutur of Giovan Battista Vico it may be aroused again by the sddhaka. This arousing is neither the intellectual movement of the Jff,6na-yoga, nor the idealistir: stand taken by the Veddnta; it is the realisation, the identification with the very power of the Mother, the radical transmutation of oneself , the resolving capacity of natura ruaturata, i.e. of that lower Prakrti which is constantly asserting itself as a necessity in ordinary persons, even if in its nobler form, which is the sattvica one. The spectacle the world offers us is not something final and inexplicable in itself , except in so far as we see it take place lrefore us while we are unable to link it up with our inner decision: but what we have to realise is that we are not only the spectators llut also and above all the actors responsible for this spectacle. We must realize that this spectacle is before us hecause it is the ever r:hanging sum total nf our sensorial perceptions, and that to view this spectacle systematically, not as a r:onfu,sion of exterior nntes but as a harmonious whole made up of many mineral, vegetable or animal elements culminating in man. is in itself an act of the mind. From the perception and the control of this ,first immediate action of the spirit the possihility of liherty arises; man begins to aequire freedom in the inner source of his being, at the point in which his realisation of himself as a conscience and the at'.tual fact of his being, ooincide in a unity which is the power process of the world. Here begins the unification of his soul with the very soul of the world, alluded to in the Tantra when they speak of the union of the deua (Siua) w\th the deui (Sakti\: a union which realised in all its degrees by virtue of the Kunclalini-Sakti, is the final consummation of the sddhuna. We do not secure liberation by ohedienee ttr a law; for such a law, notwithstanding its rnetaphysical nature, would still he a necessity, a chain o{ gold binds a l-rond, a condition

no less than a chain of irorrl we secure it hy identifying ourselves with the principle {ronr which the laws arise. Those laws are needetl only by the jiaa, the uninitiated, the non-free. who cannot stand by themselves, who c.annot find in themselves the principle of their being which is the principle of the world itself . The Tantra path is therefore an ati-dhdrmi,lt. One cannot but perceive in this doctrine a position surprisingly similar to that of Vestern philosophic idealism, there where it tends to cast off not only all traditional metaphvsics, and all myths relating to a reality that stantls apart? whether,sensorial or supersensorial, but to free itself even from the limits placed on knowledge by Emmanuel Kant, who, after all continued those myths, giving them a modern form. The path towards absolute immanence

along which Hegel started, thus getting lreyond all residual << realism >, all r:onceptions whioh see in the world a realitv, whether physical or super-physical, independent of the individual who contemplate,s it, unaware of this fundamental ar:tion of his which is contemplation, this path which was pursued to its logical oonse,quences hy Giovanni Gentile, is, even if in reflected form and in the terminology of Western philosophy. sul:rstantially the same as that which in the Tantra is looked on as the methodological premise. Vestern itlealism, carried to its logical conclusions, rnay be considered as introductory to the metaphysics of the Tantra. Thought is seized at the moment when it becornes power, whep-.it arises continuously in the r:onscience without preliminaries, a reason to itself alone;

with no need of a logical reason or of a previous thought to account for its being. It is evident that when the spiritual seeher tries to translate into action this intuition of idealism, carrying it beyond the mere plane of philosophical cognition, he will have to set aside argumentation anrl reasoning. Henr:eforth the only path he can follow will be that of concentration, rneditation, contemplation. Let us consitler the ultimate meaning of < thinking thought >: it can only hecome practical experience through the possession of the act of thinking; ancl this can only be the result of mental concentration. This is the discovery that must be made. The spirit of the Vest seeks that of the East through the positive cnnclusions to which it is led by its own philosophic concept, hy the lucid vision of << tlrinking thought >>. Tlris postulate,s

293

rneditation. [t is all a rnatter of peroeiving

this.

In the realisation of thinking thought, the Western nlan rnay Legin to artluire the experience of pure utill, in as much as he hegins to wish for something that is not required of him either by the laws of his physical nature nor by those of the abstract mental sphere. In this thought, desired for itself, antl in this will, set in motion by thought which is not subject to the physico-psychic << nature >. it is evident that man begins to realise his shiuaic essence, that is to say his liherty which places hirn beyond. all dharma. The final argument not of rhat r,r hich of sound Western rhought -alley of problemahas fallen into the blind tioism entails for those of clear understanding and who are still in touch with the inner meaning of rhe phi,losophia perennis the urgent need of meditation, dhdrana, dhydna. It is not easy to understand the value of this meditation; as the culminating point of the philosophical experience it does not imply the elimination of thought but its acquisition on a higher level at which thought has not yet taken the form of logic (dialectics) nor has yet shut itsel{ in a conceptual form. Obviously, such an acquisition is only possible if that conceptual form, that dialectical logic, have been possessed and then solved. Otherwise, while believing that one is meditating and contemplating, one falls into a state of psychic illusionism, that is to say in mental states still linked to the dynamism of the nervous system. A mind still tied to the cerebral process, ri.e. conditioned by sensorial experiences, cannot go, forward towards supersensorial experience if it has not fi.rst realised in what way and in what shape it is tied to the corporeal world. Any form of metaphysics, whether Eastern or Western, that believes it can elude the cognitive function of thought, is foredoomecl to failure. Unfortunately, today it is usual among those pursuing esoteric doctrines to turn to the Spiritual 'World, or to Tradition, or to the Yoga, in a frame of mind that takes no account of the changes that have occurred in the inner constitution of the modern man as compared to that of the man of antiquity to whom, when certain special conditions were present. Tradition spohe without need of any mediation. A well cleflned < Spiritual object >, focussed in conformity with the rules of a subtle esoteric criticism, is the starting point, and as it has been so clearly fixed one believes that

294

one is advancing towards it; but one has not realised that in order to enter into real com' munion with the super-sensorial, it is not the object of knowledge that counts but the inner act aroused by that object. The object is only a rneans, a pretext; it inay be a tree, the sun, Tradition, concept, any thing. The Spiritual 'World is not to he sought outside of the meditative activity that seeks for it, for it is in, that activity that the Spiritual World ready, expresses itself . To think of it as an r< object )) that is somewhere waiting to be known. and. that can therefore be known or not, is an attitude of mind not dissimilar to that of the ingenuous realist who believes he has before him as reality per se a ( material )), a (( nature )). Tradition therefore cannot exist apart from the act of the mind that resuscitates; it in itself ;

tradition exists which stands, before us like a n thing >>, possessing a rnysterious aspect of its own which may even he identified, and that therefore one can approach it or not, be within or outside of its << orthodoxy )), mean,s that one has ingenuously mistaken an ohject or a motive of spiritual activity for that a. tivity itself ; this would be a sort of metaphysical naturalism. We have in mind more especially the position taken up by Ren6 Gu6non, an admirable critic and exponent of doctrines, but certainly not one who points out the path for attaining the essential values that are shadowed forth in those doctrines. The error consists in seeking for the spirit or the reality outside of that inner activity in which the spirit begins to express itself. Sakti, Siuo, primordial power, the transcend,ent Ego, the o priori essential principle of heing, all that of which the mere conception, in terms familiar to the Western intellect, enabled Kant to conceive a new, even if restricted, vision of the world, in primis et ante omnio, cannot be other than action, function, pure thought, inner activity, the Ego in the moment of meditation. Kant began to falsify his initial intuition when he tried to analyse the several forms of opinions so as to derive categories from them. The'se categories, deduced from the analysis of opinions so as to deduce from them categories These categories, derived from the analysis of opinions per se, considered as products of the mind, crystalised effects of the activity nf thought, could not but be and indeed turned out to be nothing but abstract modalities

it lives there alone. To believe that

without the life of thought, yet ohliged to act

the part of spiritual functions.

Categories

indeedare not ways olthirukingbut expressions of things thought, which themselves have thought as their premise. Kant did not realise this, and therefore he oould not solve the problem of gnosiology, but made it more complicated. He had to fix limits to oognition, thus preparing, in the field of philosophy, the subjection of man to modern rcate,rialinm with all the catastrophic consequen:es tr.r hich it has given and is still giving rise. The Tantra are certainly a highly rmodern way of the Yoga; provided one really possesses the key to them. That key will always remain lost for tho'se who see in the Tantra a system that will l.er realised as a result of the mere fact of .lrnowing it; the lack of that knowledge being air obstacle to its realisation. The Tantra a.s. living metaphysics cannot be an object of kno-'rledge, a mere philosophic effort, or a chance encounter. He who without knowing them, himself knows how to live the act of meditation should be held to be in touch with their eternal e,ssence; provided ihe meditation is not studied and ahstract, determined without the possession of the problem of value, carried on as the result of r< spiritual develrrpment )) through which egotism, decked out in ascetic virtues, comes again to the fore. The meditation required must be a process of which one is master; it must be meditation per se, the living and unmistakable sign of the spirit in which the spirit itself is found. Is it possible for thought that is unaware of its limits, of its deeply-rooted conformity with sensorial experience to arrive at such a meditation? It is not possible to evade the task of a conversion cf force-thought which is a elear prohlem of cognition and therefore, in the first place, a problem of value, of awareness of what one really wants, and not the acceptance and practice of Tantra merely because one sympathises with their doctrinc. It must be living meditation, not the abstract or intellectual or sentirnental cultivation of a theme set for study, which always inevitably linhs up mental activity to its instrument, the brain. If the act of being is not itself an ideal as the world hut a mere category, and if Tanlra teach a category is an inner ar:tion, how is it possible for the act of meditation to be achieved otherwise than as the identity of being and non-being, i,e. as oreation, i.e. as power? This action that wells up within one, which presupposes nothing prior to itself, is

.

pure thought. It exists in so far as it is selfcreated, drawing on a universality that is complete in itself. It cannot exist until it is selfcreated. As soon as'it defines itself as <<being>>, (catego,ry or concept)) it cease,s to be, it dies as an abstraction or as knowledge. According to Plato, the essence of a rhing or of an idea exists I but according to the new metaphysics the existence of a cogitatum in so far as it is cogitatio is always nascent; it creates itself from that nothing which is all; the measure of its existence is its infinite capacitv lo realise itself . A truth, this, that leads us back to the central thought of the Tantra. The opening out to the Sakti according to Shri Aurohindo's modern interpretation of the Tantra in which the bhaltti and, the samarpana are nothing }ut mediating attitudes, leads up to identification with the Mother, that is to the unutterable activity of the sddhana. In irs essence it must be recognised as a purely inner act; the recovery of the original spiritual life; it is an inner deepening and strengthening that tends to the bhdaa, an expression that cannot be defined which expresses that state of perfect lucidity thanhs to which rhought surges up as being, being per se, being expressed in things, in such absolute identity with them that the Ego antl the world are one. Through the process of Vestern philosophy the requirement of the bhava is postulated as the ultimate term, represented as the achievement of ( pure thought > or creative thought which will remain as a pure and motionless mental intuition, unless the evolution of philosophy, which rakes place through the activities of such great figures as Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, Gentile, conceives a thought whose purpose is to accorr-rpany by its own development this spiritual aspect of world history. The positive response of the Orient to this need is given by the Tantra which point to the dhdrana and the dhydna as the paths leading to the bhdaa. Faithful to the principle that the spirit is a reality, let us add that, thus understood, the point of contact between East and West, sooner than in the sphere of politics or sociology or culture, can be found in the ,soul of man, who will be fit for it in so for as he finds in himself the sacred source of meditation.

Massimo Scaligero

You might also like

- Arcane SchoolsDocument381 pagesArcane SchoolsYoucef Boualala100% (1)

- Seth Miller - The Spiritual Matrix - An Anthroposophical ReadingDocument24 pagesSeth Miller - The Spiritual Matrix - An Anthroposophical ReadingPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - Intro To The Karma of UntruthfulnessDocument19 pagesTerry Boardman - Intro To The Karma of UntruthfulnessPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Almaas Loving The Truth For Its Own SakeDocument10 pagesAlmaas Loving The Truth For Its Own SakeNandaKumaraDasNo ratings yet

- Karen-Claire Voss, Imagination in Mysticism and EsotericismDocument21 pagesKaren-Claire Voss, Imagination in Mysticism and EsotericismlearntransformNo ratings yet

- Kabbalah, Assagioli and Transpersonal PsychologyDocument2 pagesKabbalah, Assagioli and Transpersonal PsychologyEsteban Molina100% (2)

- Rudolf Steiner, The Problem of Jesus and Christ in Earlier TimesDocument24 pagesRudolf Steiner, The Problem of Jesus and Christ in Earlier TimesPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- P D Ouspinsky The Fourth Way Essays On GurdjieffDocument225 pagesP D Ouspinsky The Fourth Way Essays On GurdjieffMalekit6No ratings yet

- Franz Hartmann - The Axioms of AlchemyDocument6 pagesFranz Hartmann - The Axioms of Alchemynoctulius_moongod6002No ratings yet

- Michael and The New Isis MythDocument24 pagesMichael and The New Isis Myth3adrian100% (2)

- Yoga-Practice in The Roman Catholic Church: by Franz Hartmann, M.DDocument7 pagesYoga-Practice in The Roman Catholic Church: by Franz Hartmann, M.DivahdamNo ratings yet

- Gorham Munson - Beelzebubs Tales PDFDocument2 pagesGorham Munson - Beelzebubs Tales PDFJohn Papadopoulos100% (1)

- Terry Boardman - The Roots of The New World OrderDocument79 pagesTerry Boardman - The Roots of The New World OrderPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Franz Hartmann Practical WayDocument12 pagesFranz Hartmann Practical WayesagarnagaNo ratings yet

- The Lotus Flowers, by Valentin TombergDocument15 pagesThe Lotus Flowers, by Valentin Tombergdusink100% (3)

- Owen Barfield - Worlds ApartDocument210 pagesOwen Barfield - Worlds ApartPiero Cammerinesi92% (12)

- Owen Barfield - Worlds ApartDocument210 pagesOwen Barfield - Worlds ApartPiero Cammerinesi92% (12)

- Sanskrit BooksDocument15 pagesSanskrit BooksArun Iyer100% (1)

- Fichte and SchellingDocument3 pagesFichte and SchellingStrange ErenNo ratings yet

- The Act of Consecration of Man ColorDocument11 pagesThe Act of Consecration of Man ColorNana Petrone100% (4)

- The Gāyatrī MantraDocument12 pagesThe Gāyatrī MantrasharathVEMNo ratings yet

- Institute ProspectusDocument21 pagesInstitute Prospectusso_naymaNo ratings yet

- Piercing The Veil of Language, Part IDocument7 pagesPiercing The Veil of Language, Part IBill Trusiewicz100% (1)

- 44 Letters to Gustav Meyrink: English TranslationFrom Everand44 Letters to Gustav Meyrink: English TranslationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Gandaberunda Narasimha Digbanda MantramDocument5 pagesGandaberunda Narasimha Digbanda Mantrambipintiwari73% (11)

- G. de Purucker - H. P. Blavatsky The MysteryDocument37 pagesG. de Purucker - H. P. Blavatsky The Mysterydoggy7No ratings yet

- Lok Sabha Politician PDFDocument26 pagesLok Sabha Politician PDFLasik DelhiNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Steiner, How To Know Higher WorldsDocument90 pagesRudolf Steiner, How To Know Higher WorldsFaith LenorNo ratings yet

- Lectorium Rosicrucianum DossierDocument168 pagesLectorium Rosicrucianum DossierChrystian Revelles Gatti100% (2)

- Black Illumination - Zen and The Poetry of Death - The Japan TimesDocument5 pagesBlack Illumination - Zen and The Poetry of Death - The Japan TimesStephen LeachNo ratings yet

- Atencion Según G. KühlewindDocument4 pagesAtencion Según G. KühlewindCarlos.GuioNo ratings yet

- Irene Diet - Imprisoned in The Spiritual VoidDocument42 pagesIrene Diet - Imprisoned in The Spiritual Voidstephen mattoxNo ratings yet

- A Sophia Prayer by Valentin TombergDocument1 pageA Sophia Prayer by Valentin TombergCarlos Andres Guio DiazNo ratings yet

- Tomberg and AnthroposophyDocument15 pagesTomberg and AnthroposophyfoxxyNo ratings yet

- David Tacey - Jung and The New AgeDocument13 pagesDavid Tacey - Jung and The New AgeWagner de Menezes VazNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - Grail, Study On The Mistery of Sacro AmoreDocument10 pagesMassimo Scaligero - Grail, Study On The Mistery of Sacro AmorePiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Anatomy of Angels-English-Gustav Theodor Fechner.Document18 pagesComparative Anatomy of Angels-English-Gustav Theodor Fechner.gabriel brias buendiaNo ratings yet

- Law of The Universe: The Unity of Opposites & The Doctrine of FluxDocument20 pagesLaw of The Universe: The Unity of Opposites & The Doctrine of FluxPhoenix Narajos100% (1)

- LLB I ResultsDocument10 pagesLLB I ResultsVikrant GhorpadeNo ratings yet

- (Ebook - Gurdjieff - EnG) - Heyneman, Martha - Disenchantment of The DragonDocument13 pages(Ebook - Gurdjieff - EnG) - Heyneman, Martha - Disenchantment of The Dragonblueyes247No ratings yet

- Inner DevelopmentDocument63 pagesInner DevelopmentAnonimoAnonimo167% (3)

- Valentin Tomberg - Free Hermetic-Christian Study CenterDocument6 pagesValentin Tomberg - Free Hermetic-Christian Study Centertrancegodz100% (2)

- Sayings of Jane HeapDocument6 pagesSayings of Jane HeapOccult Legend50% (2)

- Fruits of AnthroposophyDocument9 pagesFruits of AnthroposophyxavilyvNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - The Doctrine of The 'Void' and The Logic of The EssenceDocument9 pagesMassimo Scaligero - The Doctrine of The 'Void' and The Logic of The EssencePiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - The Doctrine of The 'Void' and The Logic of The EssenceDocument9 pagesMassimo Scaligero - The Doctrine of The 'Void' and The Logic of The EssencePiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Steiner - Apocalyptic WritingsDocument23 pagesRudolf Steiner - Apocalyptic WritingsPiero Cammerinesi100% (2)

- Massimo Scaligero - The LightDocument19 pagesMassimo Scaligero - The LightPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- W.J.Stein - Buddha and The Mission of IndiaDocument10 pagesW.J.Stein - Buddha and The Mission of IndiaPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Holos - The Play of DistinctionDocument18 pagesHolos - The Play of DistinctionTushita LamaNo ratings yet

- GurdjieffDocument7 pagesGurdjieffkath portenNo ratings yet

- Valentin Tomberg Symposium 2009 Report1Document5 pagesValentin Tomberg Symposium 2009 Report1SoftbrainNo ratings yet

- Connecting with Nature: Earth and Humanity – What Unites Us?From EverandConnecting with Nature: Earth and Humanity – What Unites Us?No ratings yet

- Hapur Dealers Of: Tin No. Upttno Firm - Name Firm-Address SL - NoDocument77 pagesHapur Dealers Of: Tin No. Upttno Firm - Name Firm-Address SL - NoDharma TejaNo ratings yet

- Rs - Riddles of The SoulDocument4 pagesRs - Riddles of The SoulNina Elezovic SimunovicNo ratings yet

- Valentin Tomberg and AnthroposophyDocument14 pagesValentin Tomberg and Anthroposophyteddypol100% (1)

- Terry Boardman - Third Millennium, Third Way?Document13 pagesTerry Boardman - Third Millennium, Third Way?Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- The Art of Goethean ConversationDocument8 pagesThe Art of Goethean Conversationklocek100% (2)

- Dasarathajataka - Fausboll V PDFDocument44 pagesDasarathajataka - Fausboll V PDFyolotteNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - The Ongoing Struggle For The Truth About The Child of EuropeDocument39 pagesTerry Boardman - The Ongoing Struggle For The Truth About The Child of EuropePiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Mystery of the Christ: Aspects of Christology in the Work of Rudolf SteinerFrom EverandMystery of the Christ: Aspects of Christology in the Work of Rudolf SteinerNo ratings yet

- The Light of The IDocument74 pagesThe Light of The IAndre Gas100% (2)

- The Twilight and Resurrection of Humanity: The History of the Michaelic Movement since the Death of Rudolf SteinerFrom EverandThe Twilight and Resurrection of Humanity: The History of the Michaelic Movement since the Death of Rudolf SteinerNo ratings yet

- The Myths of The Flatland - A Documentation On Kangra Miniature PaintingsDocument44 pagesThe Myths of The Flatland - A Documentation On Kangra Miniature PaintingsAnkita Laraee0% (1)

- The Coronavirus Pandemic II: Further Anthroposophical PerspectivesFrom EverandThe Coronavirus Pandemic II: Further Anthroposophical PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Irina ForewordDocument5 pagesIrina Foreword3adrianNo ratings yet

- The PHILOSOPHY OF FREEDOM of Rudolf Steiner a cure by Silvano AngeliniFrom EverandThe PHILOSOPHY OF FREEDOM of Rudolf Steiner a cure by Silvano AngeliniNo ratings yet

- Carl Unger S Theory of Epistemologyby Chris BodameDocument46 pagesCarl Unger S Theory of Epistemologyby Chris BodameCarlos.GuioNo ratings yet

- Frithjof Schuon - Sophia PerennisDocument5 pagesFrithjof Schuon - Sophia PerennisenigmarahasiaNo ratings yet

- Nicoll Maurice Psychological Commentaries On The Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky Volume 6Document205 pagesNicoll Maurice Psychological Commentaries On The Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky Volume 621nomind100% (1)

- L.V. Beethoven's Eternally Beloved Josephine Von BrunswickDocument35 pagesL.V. Beethoven's Eternally Beloved Josephine Von BrunswickAnonymous wsq3lgBpNo ratings yet

- Guido de Giorgio - The Constitution of A Traditional SocietyDocument53 pagesGuido de Giorgio - The Constitution of A Traditional Societympbh91No ratings yet

- Big DipperDocument5 pagesBig DipperJim WeaverNo ratings yet

- Hartmann, Franz - MagiconDocument23 pagesHartmann, Franz - MagiconXangotNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Perennialist SchoolDocument6 pagesIntroduction To The Perennialist SchoolqilushuyuanNo ratings yet

- Nanna or About The Inner Life of Plants-English-Gustav Theodor Fechner.Document177 pagesNanna or About The Inner Life of Plants-English-Gustav Theodor Fechner.gabriel brias buendia50% (4)

- 4 Massimo Scaligero Mysticism Sacred and Profane 1957Document5 pages4 Massimo Scaligero Mysticism Sacred and Profane 1957Pimpa Bessmcneill SylviewardesNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - Swami VivekanandaDocument5 pagesMassimo Scaligero - Swami VivekanandaPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - The Enigma of Canon XIDocument10 pagesTerry Boardman - The Enigma of Canon XIPiero Cammerinesi100% (1)

- Massimo Scaligero - Sketch of A Psychology Founded On Yoga (1955)Document7 pagesMassimo Scaligero - Sketch of A Psychology Founded On Yoga (1955)Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - What The Eightfold Path May Still Mean To Mankind (1956)Document8 pagesMassimo Scaligero - What The Eightfold Path May Still Mean To Mankind (1956)Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - Knowledge and Liberation (1954)Document6 pagesMassimo Scaligero - Knowledge and Liberation (1954)Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - Asia and The West at The End of 20th CenturyDocument10 pagesTerry Boardman - Asia and The West at The End of 20th CenturyPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Piero Cammerinesi - Preconception and Free Thought, Reflections On Judith Von HalleDocument10 pagesPiero Cammerinesi - Preconception and Free Thought, Reflections On Judith Von HallePiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - The US-China RelationshipDocument31 pagesTerry Boardman - The US-China RelationshipPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - Muslim World in 2011Document15 pagesTerry Boardman - Muslim World in 2011Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - The Cataclysm of Sept 11th 2001Document49 pagesTerry Boardman - The Cataclysm of Sept 11th 2001Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Terry Boardman - Rome and Freemasony/The Greatest IronyDocument24 pagesTerry Boardman - Rome and Freemasony/The Greatest IronyPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Piero Cammerinesi - Chi Ci Proteggerà, Luogocomune - 2009Document3 pagesPiero Cammerinesi - Chi Ci Proteggerà, Luogocomune - 2009Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Piero Cammerinesi - Happy End - Www-Effedieffe-Com 2009Document4 pagesPiero Cammerinesi - Happy End - Www-Effedieffe-Com 2009Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Massimo Scaligero - Appendices To ON IMMORTAL LOVEDocument7 pagesMassimo Scaligero - Appendices To ON IMMORTAL LOVEPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Piero Cammerinesi - Eluana, Ora Parliamone Arianna Editrice, 2009Document2 pagesPiero Cammerinesi - Eluana, Ora Parliamone Arianna Editrice, 2009Piero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- M. A. Yousuf Ali: Nattika Thrissur District Nattika Thrissur District Indian MuslimDocument9 pagesM. A. Yousuf Ali: Nattika Thrissur District Nattika Thrissur District Indian Muslimindprabin007No ratings yet

- Saundarya Lahari in English - 41 SlokamsDocument5 pagesSaundarya Lahari in English - 41 SlokamsKeerthikaNo ratings yet

- The Stories of Lord Karthikeya-XiDocument2 pagesThe Stories of Lord Karthikeya-XiRSPNo ratings yet

- 12 English Core CBSE Exam Paper PTT All India Set 1Document14 pages12 English Core CBSE Exam Paper PTT All India Set 1sandeepanNo ratings yet

- 08 Sadhana PanchakamDocument11 pages08 Sadhana Panchakammeera158100% (1)

- Data Siswa FixDocument3 pagesData Siswa FixSMAN 1 MESUJI RAYANo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 3Document76 pages11 Chapter 3singhvaageesha43No ratings yet

- Hazrat Data Ganj Bakhsh Is The Most Luminous Figure of Our HistoryDocument4 pagesHazrat Data Ganj Bakhsh Is The Most Luminous Figure of Our HistoryIqra MontessoriNo ratings yet

- Rental Tempo TravellerDocument18 pagesRental Tempo Travelleranil kumarNo ratings yet

- JOA-XII-October - December-2018-4f4ay9OBo6ShtirVV PDFDocument144 pagesJOA-XII-October - December-2018-4f4ay9OBo6ShtirVV PDFsillypoloNo ratings yet

- EEElibraryDocument4 pagesEEElibraryKaarthik Raja0% (1)

- JEET ResumeDocument3 pagesJEET ResumeAkash ModiNo ratings yet

- VedicReport8 7 202010 32 00PMDocument56 pagesVedicReport8 7 202010 32 00PMVenkatNo ratings yet

- Data CumminsvalvolineDocument2 pagesData CumminsvalvolineNavnit AbotiNo ratings yet

- About PranayamDocument30 pagesAbout PranayamRamaswamy BhattacharNo ratings yet

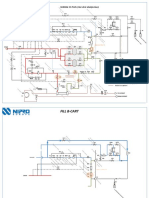

- Flowchart Surdial 55 Plus 1.0 (With Hot Citric Option)Document4 pagesFlowchart Surdial 55 Plus 1.0 (With Hot Citric Option)Hyacinthe KOSSINo ratings yet

- Nomor HP Siswa (Responses)Document36 pagesNomor HP Siswa (Responses)ibrahimovidNo ratings yet

- Bio-Code NEW UPDATE (AutoRecovered)Document111 pagesBio-Code NEW UPDATE (AutoRecovered)Patel PraweenNo ratings yet

- CatalogDocument14 pagesCatalogAmol GoreNo ratings yet

- Narayani StuthiDocument3 pagesNarayani StuthiRamesh DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Charak Chikitsa Sthana AyurDocument21 pagesCharak Chikitsa Sthana AyurHot WorksNo ratings yet