Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States. v. 2601 W. Ball Rd. - Request For Judicial Notice (SACV 12-1345)

Uploaded by

william_e_pappasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States. v. 2601 W. Ball Rd. - Request For Judicial Notice (SACV 12-1345)

Uploaded by

william_e_pappasCopyright:

Available Formats

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

MATTHEW S. PAPPAS (SBN: 171860)

DAVID R. WELCH (SBN: 251693)

LEE H. DURST (SBN: 69704)

22762 Aspan Street, Suite 202-107

Lake Forest, CA 92630

Phone: (949) 382-1485

Facsimile: (949) 242-2605

E-Mail: matt.pappas@mattpappaslaw.com

Attorneys for Claimants,

TONY JALALI and MORGAN JALAEI

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff,

v.

REAL PROPERTY LOCATED AT 2601

W. BALL ROAD, ANAHEIM,

CALIFORNIA (JALALI AND JALAEI) ,

Defendants.

__________________________________

TONY JALALI AND MORGAN JALAEI,

Titleholders.

No.: SACV 12-1345 AG (MLGx)

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR

JUDICIAL NOTICE

Date: Nov. 5, 2012

Time: 10:00 a.m.

Dept: 10 D, Santa Ana

Hon. Andrew Guilford

REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

The Claimants respectfully request, pursuant to Federal Rule of Evidence 201, that

the Court take notice of Exhibits 1 through 13 included with this request.

Exhibit 1: Letter from Scott C. Smith, city attorney for the City of Lake Forest,

California to Andr Briotte, Jr., United States Attorney for the Central District of

California dated May 3, 2011.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 1 of 109 Page ID #:56

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

2

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

Exhibit 2: Letter from Andr Briotte, Jr., United States Attorney for the Central

District of California to Scott C. Smith, city attorney for the City of Lake Forest,

California dated Oct. 7, 2011.

Exhibit 3: Opinion in California Court of Appeal case People v. Hochanadel, 176

Cal.App.4th 997 (2010).

Exhibit 4: U.S. Dept. of Justice Website page located at http://www.justice.gov

/usao/cac/Pressroom/2011/144.html accessed on February 25, 2012.

Exhibit 5: Orange County Register, Article, Costa Mesa asked feds for help in

pot crackdown, Sean Greene, Reporter, February 7, 2012.

Exhibit 6: DC ST 7-1671.05 and 7-1671.06, parts of the District of Columbia

Legalization of Marijuana for Medical Treatment Act.

Exhibit 7: Excerpts from House Report 111-202 (H.R. 3170 amended) (enacted

as Pub. Law 111-117) (111

th

Cong., 2009).

Exhibit 8: Letter from Steven R. Welk, Assistant U.S. Attorney, written to

Nutritional Concepts in Costa Mesa, California dated Jan. 18, 2012.

Exhibit 9: Text of the Legalization of Marijuana for Medical Treatment

Initiative Amendment Act of 2010.

Exhibit 10: A true and correct copy of a Webpage from the National Cancer

Institute, a part of the federal National Institutes of Health, from March, 2011.

Exhibit 11: A true and correct copy of a letter from Robert Petzel, Undersecretary

of Health for the Veterans Department, dated July, 2010.

Exhibit 12: A true and correct copy of a Veterans Administration Directive 2011-

004.

Exhibit 13: Opinion in California Court of Appeal case Qualified Patients Assn

v. City of Anaheim, 187 Cal.App.4th 734 (2010).

//

//

//

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 2 of 109 Page ID #:57

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

3

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

BASIS FOR REQUESTING JUDICIAL NOTICE

Judicial notice is appropriate for each of the items submitted by the Claimants

pursuant to Fed. R. Evid. 201. Under Rule 201(b), the Court may take judicial notice of

any matter not subject to reasonable dispute in that it is either (1) generally known

within the territorial jurisdiction of the trial court or (2) capable of accurate and ready

determination by resort to sources whose accuracy cannot reasonably be questioned.

Judicial notice may be taken at any stage of the proceeding. Fed. R. Evid. 201(f); Lowry

v. Barnhart, 329 F.3d 1019, 1024 (9th Cir. 2003); Bryant v. Carleson, 444 F.2d 353, 357-

58 (9th Cir. 1971). A Federal Court takes judicial notice of facts if requested by a party

and supplied with the necessary information. Fed. R. Evid. 201(d).

EXHIBITS 1 AND 2

This Court may take judicial notice of Exhibits 1 and 2 because each of those

exhibits is a matter of public record. See, e.g., Del Puerto Water Dist. v United States

Bureau of Reclamation, 271 F.Supp.2d 1224, 1234 (E.D. Cal. 2003) (taking judicial

notice of public documents, including Senate and House Reports); Feldman v Allegheny

Airlines, Inc. (D. Conn. 1974) 382 F.Supp. 1271, reversed on other grounds 524 F.2d 384

(2nd Cir. 1975) (taking judicial notice of data contained in Presidents Economic Report).

A Court may take judicial notice of records and reports of administrative bodies.

Interstate Natural Gas Co. v. Southern California Gas Co., 209 F.2d 380, 386 (9th Cir.

1953).

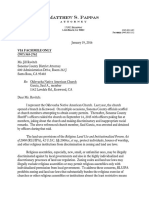

Exhibit 1 is a letter from Scott C. Smith written to Andr Briotte, Jr., the United

States Attorney for the Central District of California. In the letter, Mr. Smith states that

his law firm serves as the city attorney for the City of Lake Forest (LAKE FOREST).

The letter is signed by Mr. Smith. It is written by Mr. Smith on behalf of LAKE

FOREST in his firms capacity as city attorney for LAKE FOREST, a government entity.

Accordingly, the letter is not subject to reasonable dispute and its authenticity as well as

accuracy is not in question.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 3 of 109 Page ID #:58

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

4

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

The letter is relevant because it shows that California cities are engaged in an

effort to rid themselves of all medical marijuana collectives and it asserts that California

appellate courts are interfering with the cities ability to accomplish that goal (see, e.g.,

Ex 1, at p. 1, showing the City frustrated because the California Court of Appeal once

again stepped in to block enforcement ...). This same sentence shows some or all of the

collectives are operating properly because it is unreasonable to even consider the state

appellate court would allow entities violating state

1

law to remain operating. Moreover,

the letter shows the appellate court has intervened multiple times because that city uses

the word again describing one particular occasion the appellate court stepped in to

block enforcement apparently preventing it from being able to rid itself of the

collectives for nearly two (2) years (see, e.g., Ex. 1 at p. 2, claiming it has been stymied

at every turn in its nuisance abatement efforts). In the letter, LAKE FOREST asks the

United States Attorney to take action on its behalf (see, e.g., Ex 1, at p. 2).

Exhibit 2 is a letter from Andr Briotte, Jr. to Mr. Scott Smith. Mr. Briotte is the

United States Attorney for the Central District of California. The letter is on the official

letterhead of the U.S. Attorneys office. It is signed by Mr. Briotte. It follows there is no

basis for reasonably questioning the letters authenticity and accuracy. The letter is

relevant because it is consistent with the closure order letters sent out by Plaintiff United

States of America (UNITED STATES) to patient collectives and shows the position

taken in respect to such collective, including the collectives referred to in the Lake Forest

letter for which the state appellate court has blocked enforcement actions. The letter is

further relevant because it shows the United States Attorney is taking action in California

despite Congresss action in the federal District of Columbia (Ex. 2, at p. 1, e.g., persons

engaged in any marijuana activities are violating federal law regardless of state law.)

EXHIBIT 3

Exhibit 3 is a true and correct copy of People v. Hochanadel, 176 Cal.App.4th 997

(2010) (Hochanadel), a California Court of Appeal opinion. Courts may take judicial

1

If collectives were violating state law, the City would have brought criminal charges

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 4 of 109 Page ID #:59

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

5

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

notice of their own files, as well as the files of other courts of competent jurisdiction,

including briefs, pleadings, and rulings. See, e.g., Reyns Pasta Bella, LLC v. Visa USA,

Inc., 442 F.3d 741, 746 n.6 (9th Cir. 2006) (taking judicial notice of briefs in another

court); Meredith v. Oregon, 321 F.3d 807, 817 n.10 (9th Cir. 2003) (taking judicial notice

of Claimants filing in state court). Specifically, federal courts may take judicial notice

of proceedings in other courts, both state and federal, if those proceedings have a direct

relation to matters at issue. Allen v. City of Los Angeles, 92 F.3d 842 (9th Cir. 1992).

Likewise, federal courts may take judicial notice of state agency records that are not

subject to reasonable dispute. See City of Sausalito v. O'Neill, 386 F.3d 1186, 1224 n. 2

(9th Cir. 2004).

The opinion in Hochonadel is relevant because it shows, contrary to the

statements made by LAKE FOREST city attorney Smith and United States Attorney

Briotte, that California law does not prohibit storefront dispensaries. Hochonadel

demonstrates the mistaken assumption of a police officer in assuming that all store-front

dispensaries are prohibited under California law (Ex. 3 at p. 29, Detective Garcia's

erroneous conclusion that store front dispensaries could never operate legally did not

render him incompetent to author the search warrant). In fact, under Hochonadel,

storefront dispensaries are anticipated and acceptable when operating in compliance with

California Health and Saftey Code 11362.5 (CUA) and 11362.7 (MMPA) as well as

the 2008 California Attorney General Guidelines on the Safety and Non-Diversion of

Marijuana Grown for Medical Use. (See, e.g. Ex. 3 at pp. 2-3, [W]e also conclude that

storefront dispensaries that qualify as cooperatives or collectives under the CUA and

MMPA, and otherwise comply with those laws, may operate legally). Hochonadel is

likewise relevant because the case provides, contrary to the statements of the United

States Attorney and city attorney Smith, the Ca. MMPAs specific itemization of the

marijuana sales law indicates it contemplates the formation and operation of medicinal

marijuana cooperatives that would receive reimbursement for marijuana and the

since the CUA and MMPA do not protect those who are out of compliance.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 5 of 109 Page ID #:60

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

6

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

services provided in conjunction with the provision of that marijuana. Ex. 3 at 11

quoting People v. Urziceanu, 132 Cal.App.4th 747 (2005), 785.

EXHIBIT 4

Exhibit 4 is a page from the U.S. Department of Justice website. Courts may take

judicial notice of matters of public record, including documents appearing on a

government website. See, e.g., Daniels-Hall v. Natl Educ. Assn, 629 F.3d 992, 998-99

(9th Cir. 2010) (taking judicial notice of information displayed publicly on school district

website); Shaw v. Hahn, 56 F.3d 1128, 1129 n.1 (9th Cir. 1995) (taking judicial notice of

matter of public record). See also Cota v. Maxwell-Jolly, 688 F. Supp. 2d 980, 998 (N.D.

Cal. 2010) (The Court may properly take judicial notice of the documents appearing on

a governmental website); Paralyzed Veterans of Am. v. McPherson, No. 06-4670, 2008

WL 4183981, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2008) (taking judicial notice of a letter appearing

on the Secretary of States website).

Exhibit 4 is relevant because it shows the U.S. Attorney is stepping in when Ca.

cities ask the federal government to close all collectives. It shows the U.S. Attorney

believes that all collectives are illegal under Ca. law which is incorrect and therefore

shows the Government is taking action that contravenes state sovereignty and state law.

It also shows that Article II branch has not followed the limited scope holdings from the

Gonzales v. Oregon case. Additionally, the letter includes a quote from U.S. Attorney

Andr Briotte, Jr. providing, [W]hile California law permits collective cultivation of

marijuana in limited circumstances, it does not allow commercial distribution through the

store-front model we see across California. As noted, Ex. 3, the Hochonadel appellate

opinion, references Californias marijuana sales law that anticipates monetary

transactions and specifically holds that storefront dispensaries are lawful when operated

in conformance with the states CUA and MMPA. The U.S. Attorneys webpage also

states that medical marijuana collectives have been ordered to close by his office in

areas where local officials have taken action to eliminate marijuana stores and have

asked the [federal] government for assistance.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 6 of 109 Page ID #:61

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

7

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

EXHIBIT 5

Exhibit 5 is a February 7, 2012 article from the Orange County Register. As a

general rule, the Court may take judicial notice of the content of media articles. See, e.g.,

League of United Latin American Citizens v. Wilson, 131 F.3d 1297, 1305 (9th Cir.

1997) (quoting news articles concerning legal challenge filed to block the implementation

of a state law); Heliotrope Gen., Inc. v. Ford Motor Co., 189 F.3d 971, 981 (9th Cir.

1999) (taking judicial notice of information contained in news articles); Ieradi v. Mylan

Laboratories, Inc., 230 F.3d 594, 597-98 (3rd Cir. 2000).

The Orange County Register article is relevant because it provides that, [M]onths

before federal authorities shut down dozens of medical marijuana facilities, the city

[Costa Mesa] asked them for help. This is relevant in this case because it shows that the

federal government is stepping in to do what cities cannot do under state civil/criminal

laws. If the collectives were violating state law, the cities have the ability to shut them

down through arrests, civil nuisance proceedings, etc. They have, in fact, done so when

such illegal activity is occurring. The cities are instead calling in the federal government

to do what they cannot do to entities operating legally under state law.

EXHIBIT 6

Exhibit 6 is a copy of DC ST 7-1671.05 and 7-1671.06 provided on the federal

District of Columbia website by West Publishing. Federal courts may take judicial notice

of state agency records that are not subject to reasonable dispute. See City of Sausalito v.

O'Neill, 386 F.3d 1186, 1224 n. 2 (9th Cir. 2004). Courts may also take judicial notice of

public records. Shaw v. Hahn, 56 F.3d 1128, 1129 n.1 (9th Cir. 1995) (taking judicial

notice of matter of public record). See also Cota v. Maxwell-Jolly, 688 F. Supp. 2d 980,

998 (N.D. Cal. 2010) (The Court may properly take judicial notice of the documents

appearing on a governmental website). Exhibit 6 is relevant because it shows the law

Congress allowed the voters of Washington D.C. to vote-on and then implement. It is

also relevant because it shows DC ST 7-1671.05 and 7-1671.06 legalize and authorize

medical marijuana dispensaries and cultivation centers. If California voters were treated

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 7 of 109 Page ID #:62

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

8

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

equally in terms of their right to vote, they could, like the District of Columbia, legislate

in a manner that prevents the kinds of problems COSTA MESA officials say lead to the

wild wild west in Exhibit 5.

EXHIBIT 7

Judicial notice is appropriate for Exhibit 7 pursuant to Fed. R. Evid. 201. Under

Rule 201(b), the Court may take judicial notice of any matter not subject to reasonable

dispute in that it is either (1) generally known within the territorial jurisdiction of the trial

court or (2) capable of accurate and ready determination by resort to sources whose

accuracy cannot reasonably be questioned. Judicial notice may be taken at any stage of

the proceeding. Fed. R. Evid. 201(f); Lowry v. Barnhart, 329 F.3d 1019, 1024 (9th Cir.

2003); Bryant v. Carleson, 444 F.2d 353, 357-58 (9th Cir. 1971). A Federal Court takes

judicial notice of facts if requested by a party and supplied with the necessary

information. Fed. R. Evid. 201(d).

EXHIBIT 8

Exhibit 8 is a letter from Steven Welk, Assistant U.S. Attorney, to Nutritional

Concepts, a Costa Mesa patient group. The letter is on the official letterhead of the U.S.

Attorneys office. It is signed by Mr. Welk. Accordingly, the letter is not subject to

reasonable dispute and its authenticity as well as accuracy is not in question. The letter is

relevant because it shows Costa Mesa collectives have been ordered to close by the

UNITED STATES. It further shows the position taken by the UNITED STATES that

there is no medical marijuana in California notwithstanding Congresss recognition that

marijuana has medical value in the federal District of Columbia. (Ex. 2, at p. 1, e.g.,

persons engaged in any marijuana activities are violating federal law regardless of state

law.) The letter is further relevant because it is shows that Plaintiff UNITED STATES

has ordered closure in a manner that deprives collectives of procedural due process.

Additionally, it shows that the UNITED STATES is taking action against a large number

of collective groups because it includes a blanket notice e-mail address for response.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 8 of 109 Page ID #:63

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

9

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

EXHIBIT 9

Exhibit 9 is a matter of public record. The exhibit is the official text of the D.C.

Legalization of Marijuana for Medical Treatment Initiative Amendment Act of 2010 and

may be judicially noticed. See, e.g., Del Puerto Water Dist. v United States Bureau of

Reclamation, 271 F.Supp.2d 1224, 1234 (E.D. Cal. 2003) (taking judicial notice of public

documents, including Senate and House Reports); Feldman v Allegheny Airlines, Inc. (D.

Conn. 1974) 382 F.Supp. 1271, reversed on other grounds 524 F.2d 384 (2nd Cir. 1975)

(taking judicial notice of data contained in Presidents Economic Report). A Court may

take judicial notice of records and reports of administrative bodies. Interstate Natural

Gas Co. v. Southern California Gas Co., 209 F.2d 380, 386 (9th Cir. 1953). It is relevant

because it supports emerging awareness for purposes of substantive due process as

argued by the Claimants in this case.

EXHIBIT 10

Exhibit 4 is a government webpage from the National Cancer Institute from

March, 2011. Courts may take judicial notice of matters of public record, including

documents appearing on a government website. See, e.g., Daniels-Hall v. Natl Educ.

Assn, 629 F.3d 992, 998-99 (9th Cir. 2010) (taking judicial notice of information

displayed publicly on school district website); Shaw v. Hahn, 56 F.3d 1128, 1129 n.1 (9th

Cir. 1995) (taking judicial notice of matter of public record). See also Cota v. Maxwell-

Jolly, 688 F. Supp. 2d 980, 998 (N.D. Cal. 2010) (The Court may properly take judicial

notice of the documents appearing on a governmental website); Paralyzed Veterans of

Am. v. McPherson, No. 06-4670, 2008 WL 4183981, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2008)

(taking judicial notice of a letter appearing on the Secretary of States website). It is

relevant because it supports emerging awareness for purposes of substantive due

process as argued by the Claimants in this case.

EXHIBIT 11

This Court may take judicial notice of Exhibit 11 because: 1) is a matter of public

record; and 2) it is self-authenticating through the signature of Dr. Petzel, which appears

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 9 of 109 Page ID #:64

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

10

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

directly on the letter. See, e.g., Del Puerto Water Dist. v United States Bureau of

Reclamation, 271 F.Supp.2d 1224, 1234 (E.D. Cal. 2003) (taking judicial notice of public

documents, including Senate and House Reports); Feldman v Allegheny Airlines, Inc. (D.

Conn. 1974) 382 F.Supp. 1271, reversed on other grounds 524 F.2d 384 (2nd Cir. 1975)

(taking judicial notice of data contained in Presidents Economic Report). A Court may

take judicial notice of records and reports of administrative bodies. Interstate Natural

Gas Co. v. Southern California Gas Co., 209 F.2d 380, 386 (9th Cir. 1953).

Exhibit 11 is a letter written by Dr. Robert Petzel, Undersecretary for the Veterans

Department, a unit of the federal government. The letter is signed by Dr. Petzel. It is

written by Dr. Petzel on Veteran Department letterhead, a government entity.

Accordingly, the letter is not subject to reasonable dispute and its authenticity as well as

accuracy is not in question. It is relevant because it supports emerging awareness for

purposes of substantive due process as argued by the Claimants in this case.

EXHIBIT 12

Judicial notice is appropriate for Exhibit 12 pursuant to Fed. R. Evid. 201. Under

Rule 201(b), the Court may take judicial notice of any matter not subject to reasonable

dispute in that it is either (1) generally known within the territorial jurisdiction of the trial

court or (2) capable of accurate and ready determination by resort to sources whose

accuracy cannot reasonably be questioned. Judicial notice may be taken at any stage of

the proceeding. Fed. R. Evid. 201(f); Lowry v. Barnhart, 329 F.3d 1019, 1024 (9th Cir.

2003); Bryant v. Carleson, 444 F.2d 353, 357-58 (9th Cir. 1971). A Federal Court takes

judicial notice of facts if requested by a party and supplied with the necessary

information. Fed. R. Evid. 201(d). It is relevant because it supports emerging

awareness for purposes of substantive due process as argued by the Claimants in this

case.

//

//

//

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 10 of 109 Page ID #:65

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

11

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

EXHIBIT 13

Exhibit 3 is a true and correct copy of Qualified Patients Assn v City of Anaheim,

187 Cal.App.4th 734 (2010) (Qualified Patients), a California Court of Appeal opinion.

Courts may take judicial notice of their own files, as well as the files of other courts of

competent jurisdiction, including briefs, pleadings, and rulings. See, e.g., Reyns Pasta

Bella, LLC v. Visa USA, Inc., 442 F.3d 741, 746 n.6 (9th Cir. 2006) (taking judicial

notice of briefs in another court); Meredith v. Oregon, 321 F.3d 807, 817 n.10 (9th Cir.

2003) (taking judicial notice of Claimants filing in state court). Specifically, federal

courts may take judicial notice of proceedings in other courts, both state and federal, if

those proceedings have a direct relation to matters at issue. Allen v. City of Los Angeles,

92 F.3d 842 (9th Cir. 1992). Likewise, federal courts may take judicial notice of state

agency records that are not subject to reasonable dispute. See City of Sausalito v.

O'Neill, 386 F.3d 1186, 1224 n. 2 (9th Cir. 2004).

The opinion in Qualified Patients is relevant because it shows the City of

Anaheim was subject to a case noting it is a creature of the state and not federal

government, that it cannot be conscripted to enforce federal law, and that it cannot ban

collectives based solely on alleged federal marijuana illegality. After this case was

handed down, the City of Anaheim, following the lead of its co-counsel, Best, Best, and

Krieger, in nuisance abatement cases previously filed, has asked the federal sovereign to

do what it cannot do under state law close all the collectives in its borders.

CONCLUSION

The authenticity and content of the exhibits under submission are not subject to

any reasonable dispute because they are capable of accurate and ready determination by

reliable sources here, government websites, the website of a reputable public media

source (the Orange County Register), or court records. Likewise, for several exhibits, the

authenticity and content are not subject to reasonable dispute because they show the

signature of the person executing the document, are official statutes, or are public records

and filings of a court of competent jurisdiction.

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 11 of 109 Page ID #:66

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CLAIMANTS FIRST REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE

12

L

A

W

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

M

A

T

T

H

E

W

P

A

P

P

A

S

2

2

7

6

2

A

S

P

A

N

S

T

.

,

#

2

0

2

-

1

0

7

L

A

K

E

F

O

R

E

S

T

,

C

A

9

2

6

3

0

(

9

4

9

)

3

8

2

-

1

4

8

5

In sum, the Court may properly take judicial notice of the above-referenced

documents. Accordingly, the Claimants request that the Court so take notice of the

items.

DATED this 1

st

day of October, 2012.

_________________________________

Matthew Pappas

Attorney for Claimants

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 12 of 109 Page ID #:67

EXHIBIT 1

EX. PG.1

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 13 of 109 Page ID #:68

" ,III \

" ':. ', : ' ,'

. p. : .. ;: ... J

':"" "." 1 ' .1; :

Scott C, Smith

:"U;:'; :;I}],'S56:

';c.; ..")tt : ...., ":" . '"

AnJrc Ilirollc. Jr.

REST BEST KHltGER

, \\"1011" ,\",,\1' L\\\

:: . .. .... . : ..

2011

SlalCS (\:lIlral Ill' ( 'alilil("uia

31:! N, Spring Sireet

1.1IS A ngclcs, (' A <)0012

Mr,

.

"

.:..:.,

:'.1t . '. l ' J" . :' ; ''' ,

::-u'; J I .l. ,t )

e.;",:. : \\'1

I I

?!, . :}.' ..

This office as th..: Cit) fllr Ihe City or I.ake Foresl. Lake Fllrcst,

in Orange C\.lllIIl)' , is a Cily or approxillliltdy 75,000 petll'k in roughly lCd, squan: lIIiks, \\\:

wrile to infcmn you ur the prcsent silualilln wilh marijuana sales within I.ak..: Forest and the

CilY's dliJr\s 10 address Ihal silmlliul1, alld II) seek ynllr assislance in lhe maller. We arc

presclltly aware of 12 operating slorc:fwnt marijuana dispensaries within Ihe City, Of Ihese,

eight Im;alcd ill a single cOllllllercial strip I:cntcr Illeal..:d al :::!4602 Raymond Way, Ileaf

Inlerslate -tOS al EI Torn Wc 1\;1\'1.: rl.'cemly discll\'en:d th .. t Ihese eight. as well ;IS unc

uther dispensary across thl: street al Raymond Way, arc lucated less than 60() fect

from a MUlltess()ri school serving P/'C-SdlOOI and killdcrgflr\(,:n students.

The City of I.ake FUI'I.'SI has hec.:1\ ill\'tlJ\'cd ill k'nglhy ;Inti cxpcnsive litigatioll tu ahate

these t1ispen:;aries, \\hil.:h in auuiliun to Ibgranl violation (.f leJcral n;m:lItics laws,

roulinely ereale :;ecolllbry la\\' cntiJrCl'J1h.'llt ;111.1 land lISl' issllcs for the Cily, The City is

concerncd thaI Jill.' 10 thc largc mass (If tlll,:se bllSilll:Sscs and Iwhat WI.' beil c\'cl arc th..: huge

receipts Ihey llcrivc frolll Ihese il kgal al.:li\-ilil's, the)' \\ j II t'onlillllc to cOlllmit v,lsl resuurces In

opposing nul' abalellll'nl d"lims, The Iandlt'l'ds tIl' these husilll'SSCS h.we indicall'd Ihat thcse

.:onl i Ill/cd i IIq,!al tellandt.'s are .oj lIsl husi Ilc:;s"

Ihe City Like hll"l,,'st ' s "nllill;! rcglll ;IIIC1Us dll 11111 pl.'rlll;t marijuana dispensarics: in

Ihe CilY' s :\,1 lin ie.: ipal ('tldc prohihits lise that villl .. l..:s either slate lIr Ii:Jcral law,

At' t'ordingly, Ihe City has attempted lIearl y t\\O years now It) rid the C.lllllllllllily lll' Ihese

sltH'l'lroUI dispt'llsarit.'s by Illlis:lncl.':lh;Ill' 1I11.'Ilt 1;l\\suils ill COllrt ulllkr the City's

local land-usc allth cllnsistelll \\,ilh C'alililnl ia stak I;tw, I. a ,,,I May \\1.' wen: slIcct.!ssful ill

in,illlll'lillJls Iht.' di"pellsaries, Sen,'r:!1 ur the ddi.:nd'lllls arrl!aled.

hO\\'I:\I..'r, .lIld 11ll' ('alit'"rnia ('ollrl lit' ' \PPl';d prtllllptly Ihl' cnli.,recllleill Clf th.lse

in,illlll.:titllls , 1"hI.' apl'eal-; h;l\l' y .. ' t III h..: t!I.'(,' lll..-d .111 Iheir 1111,: ' ilS, :lIld Iho.: disp..:no.;:.rks h,,\\..' 1'1\:\.'1\

alhl\\,:d Itl rl.'lIlalll <llk'lI \\ ith "tlll'l.' tll:.1 link' (lthl.'r dd"o.:mbnts !la\''': pUI'pt>rkdly

EX. PG. 2

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 14 of 109 Page ID #:69

:\nure Hiwtlc, Jr.

.1.

Page 2

,.

't:!(lscd" their shops, \)nly 10 11:1\e .1 l1lari.illan;1 llisp.,:ns<lry in Ih .... Ille;lIioll undcr

alkgedly\lifkrelll operator" whulhe:n claim 11111 Itl he hound hy Ihl' inj lllldi(lll.

the Cali fornia Icg.islatllre l'n01l.:ll.:1.I legislat ion efl'ccli\'l' January I. 201 I Ihal

prohibits nwrijuana Jispcnsari .... ::; \\ ithin 600 k .... 1 (If sdhlols. \Vh .... n Ihe Jisclln:rco Ihal nin ....

of Ihese arc \\ ithin thaI distance of a :;ell(IOI. \ ....1: againsl sought and oblained - a

tClllpllrary rcslr;lining order fmm Ih .... stale court to dose those dispcn:;aries. 110\\'\:\'er, bdorl! th ....

l)edt'r to ::;hl.)\\ calise: rc pn:liminary injullctiOIi ClHild " .... n bc hcurd (111 Ihat matler, Ihe C'"lilornia

Court of Appeal Ollce again stepped in 10 hlock cnlllfce:IIlCIlI of the injullclioll, In shur\. the City

has occn SI) l1lied al ... ery 111m in its legal dforlS lu deal with thl..' probh:111 or commercial

milrijuan:1 d i spcns:uics.

We an: aware of U.S, DepanlllC'lIt llf Justi l.:es pusition, outlined in the :!O1)9 Ogden

Memor<lndulIl fcgarding resoun;eallocation priori tics visa-\'i:> scrit1llslyi II individuals who usc

marijll<lIl<l as part uf a lreatment fegilllt."11 ill wlllpli:lIlc .... wilh state law.

as well <'IS its policy of continuing III Ihe CIllllWllcd Substalll:cs Act \';gofllllsly against

individuals and organiz..1tions that participate ill unl'l\vful manufacturing alld distrihutiull of

marijuana, ev .... n if such activities >Ire pcrmilh:d ulIlkr stille I;IW. We alsu <I,varc thaI your

colll!:tguc! in thc r--;ll/1hl'W District, Ms. Haag, reiterateu in " Fcbru'lrY I. :!O II kiter to lhe

Oakland CilY Attorne)' (a copy of which is I!ndoscd hen.: for your rdcrell1.:e) the Justice

Department's position thai it will cniixn: the ('SA especially to prohibit the commercial

manufacture :md distrihution of lllarijuan;1.

WI! seck yuur oflke:'s assistance in combating the ilkgal stun:fr01l1 marijuana

dispensaries in LIke Forest lhat openly nUll! li.:deral. local. .lIul c\'cn slate law. yct have thus far

cffectively cV:lJcd Ihc City'S legal effurts tu duse Ih'::111. We wclwllle the opportunity to mc!!t

with you or .mother member of your oflice to disclIss how we can work logcthl..'r 10 address this.

Enl'i(lsllrc

S!,;l)1I C. Smith

kffrey V. DUlin

t bl1id Roherls

of Ikst Ikst &. f..:.ril' g.,:r I.LP

('it Y: \lIorney

( ' it ) lIfL ..

cc : Ikllll isl' \vil/ett. Chief. Santa ,\11;( Di\'i "idlt

Rphert City M;III;tger, Cily of I.:IJ...,: (-'..rl'st

EX. PG. 3

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 15 of 109 Page ID #:70

EXHIBIT 2

EX. PG. 4

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 16 of 109 Page ID #:71

Andr4 BtroueJr.

United States Attorney

(213) (telephone)

(2 13) (facsimile)

October 7, 2011

Scott C. Smith, Esq.

City Attorney

City of Lake Forest

Best, Best, & Krieger, LLP

5 Park Plaza, Suite 1500

Irvine, California 92614

Dear Mr. Smith:

U. S. Department of Justice

U"ited Slales AI/oriley

Celltral Dislr;cl of Califo",;a

Ullited States CorU'thO/lse

3 J 2 North Spring Street

Los Angeles. California 90012

O' II.

I write to respond to your earlier letter seeking the assistance of my office with the

City of Lake Forest's efforts to combat commercial marijuana stores operating in violation of

local ordinances and regulations, and other laws. We have received similar requests from other

municipalities throughout the Central District of California (the District). As a result, in

conjunction with federal and local law enforcement agencies, we have carefully examined the

situation in Lake Forest, and the problem of commercial marijuana operations in the District.

The Department of Justice has stated on many occasions that it is conunitted to the

enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in all States, including those like California

that have enacted some form of legislation relating to the medical use of marijuana. Congress

has dctennined that marijuana is a dangerous drug and that the illegal distribution and sale of

marijuana is a serious crime that provides a significant source of revenue to large scale criminal

enterprises, gangs, and drug cartels. While it would not be an efficient or reasonable use of

federal resources to focus enforcement efforts on individuals with cancer or other serious

illnesses who use drugs as part of a recommended treatment regime consistent with applicable

state law or advice from their healtheare professionals, the prosecution of significant traffickers

of illegal drugs, including marijuana, remains a core priority of the Department.

Persons who are in the business of cultivating, selling, Or distributin mari'uana and

those who knowingly facilitate such activities, are in violation of the CSA re ardless of state law.

Such persons are subject to federal criminal and civil enforcement actions. These include, but

are not limited to, actions to enforce the criminal provisions of the CSA such as Title 21, United

States Code, Section 841, which makes it illegal to manufacture, distribute, or possess with intent

to distribute any controlled substance including marijuana; Title 21, United States Code, Section

856, which makes it illegal to knowingly open, lease, rent, maintain, or use property for the

EX. PG. 5

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 17 of 109 Page ID #:72

f' ~ .

manufacturing, storing. or distribution of controlled substances including marijuana; and Title

21, United States Code, Section 846. which makes it illegal to conspire to conunit any of the

crimes set forth in the CSA. Federal money laundering and related statutes also prohibit a variety

of different types of financial activity involving the movement of drug proceeds, and the

govenunent may also pursue civil injunctions or the forfeiture of drug proceeds. property

traceable to such proceeds, and property used to facilitate drug violations.

In recent years, commercial marijuana operations have proliferated in this District,

including in cities like yours that have vigorously opposed them. This expansion has been driven

primarily by the profits generated by marijuana sales. The intent behind California's medical

marijuana laws may have been a well-meaning desire to help the seriously ill. However, based

on federal investigations, discussions with district attorneys, municipalities, and numerous law

enforcement agencies, it is clear that, in reality. and in direct violation of these state laws,

virtually all the marijuana stores operating in the this District are profit-making enterprises. In

addition to the local problems posed by these stores that you have outlined in your letter,

marijuana is being illegally grown on public and private lands to support the commercial

distribution at stores, causing harm to the environment and surrounding communities. Moreover,

marijuana and marijuana profits associated with these operations travel frequently throughout the

state and are being moved between California and other states throughout the country.

In response to this problem, my office is working with federal, state, and local law

enforcement agencies to make renewed efforts to combat the commercial marijuana industry in

your city and throughout the District. In addition to undertaking criminal prosecutions and other

enforcement actions, this office is today sending out letters to the property owners and landlords

of the marijuana stores in your city and nearby areas. These ielters provide formal notice that the

properties in question are being used to possess, distribute. or cultivate marijuana in violation of

fcderallaw, and that such activity may subject the property owners to criminal prosecution, fines,

and forfeiture of their properties as well as any money they receive from the distribution of

marijuana by the stores. At three properties -located in Lake Forest, Wildomar, and Montclair-

where the government believes that the property owners were well aware of the marijuana

operations in their properties. my office is filing civil complaints in federal court seeking

forfeiture of the properties without a preliminary warning letter. We have also acted with the

help of I.R.S. to seize a bank account containing rent money from marijuana stores. These

actions are of course only the beginning of what will be on-going efforts to help remove these

operations.

In choosing to take theses actions in your city and nearby conununities, we have noted the

substantial efforts your city has made on its own to combat commercial operations through both

civil and criminal enforcement. The commercial marijuana industry is illegal and subject to

federal enforcement wherever it is found. However, given the number of stores and other

operations in the District, in considering the efficient expenditure of federal resources, this office

will continue to give extra consideration to communities like yours that have made it clear that

commercial marijuana operations are unwanted and that have made, and continue to make, all

2

EX. PG. 6

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 18 of 109 Page ID #:73

,.

reasonable efforts to identify and remove commercial marijuana operations. This office caMot

efficiently address this problem alone. We look forward to working together with your city and

our federal, state, and local Jaw enforcement partners to uphold the law and help your

community.

United States Attorney

3

EX. PG. 7

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 19 of 109 Page ID #:74

EXHIBIT 3

EX. PG. 8

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 20 of 109 Page ID #:75

Filed 8/18/09

CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION

COURT OF APPEAL, FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT

DIVISION ONE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

THE PEOPLE, D054743

Plaintiff and Appellant,

v. (Super. Ct. No. INF056902)

STACY ROBERT HOCHANADEL et al.

Defendants and Respondents.

APPEAL from a judgment of the Superior Court of Riverside County, David P.

Downing, Judge. Reversed.

Rod Pacheco, District Attorney, and Jacqueline C. Jackson, Deputy District

Attorney, for Plaintiff and Appellant.

Marylou Hilbert, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and

Respondent Stacy Robert Hochanadel.

James M. Crawford, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and

Respondent John Reynold Bednar.

EX. PG9

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 21 of 109 Page ID #:76

Stephen M. Hinkle, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and

Respondent James Thomas Campbell.

In this case we are presented with two questions regarding the legality of

storefront dispensaries that provide medical marijuana pursuant to the Compassionate

Vse Act (CVA), approved by voters in 1996 under Proposition 215, and its implementing

legislation, the Medical Marijuana Program Act (MMP A).

First, did the MMPA unconstitutionally amend the CVA when it authorized

"cooperatives" and "collectives" to cultivate and distribute medical marijuana?

Second, did the court err in quashing a search warrant for a storefront medical

marijuana dispensary called CannaHelp located in the City of Palm Desert, California,

and dismissing the criminal charges against the defendants Stacy Robert Hochanadel,

James Thomas Campbell and John Reynold Bednar (collectively, defendants), who

operated CannaHelp, based on its findings that (1) CannaHelp was a legal "primary

caregiver" under the CVA and MMPA; and (2) the detective that authored the search

warrant affidavit was not qualified to opine as to the legality of CannaHelp?

We conclude the MMPA's authorization of cooperatives and collectives did not

amend the CVA, but rather was a distinct statutory scheme intended to facilitate the

transfer of medical marijuana to qualified medical marijuana patients under the CVA that

the CVA did not specifically authorize or prohibit. We also conclude that storefront

dispensaries that qualify as "cooperatives" or "collectives" under the CVA and MMPA,

and otherwise comply with those laws, may operate legally, and defendants may have a

2

EX. PG.10

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 22 of 109 Page ID #:77

defense at trial to the charges in this case based upon the CUA and MMPA. We further

conclude, however, that the court erred in finding that CannaHelp qualified as a primary

caregiver under the CUA and MMPA and in finding that the detective who authored the

search warrant affidavit was not qualified to opine as to the legality of CannaHelp's

activities. We conclude the facts stated in the search warrant affidavit provided probable

cause the defendants were engaged in criminal activity, and, even if the search warrant

lacked probable cause, the author of the search warrant affidavit acted in reasonable

reliance on its validity. Accordingly, the court erred in quashing the search warrant and

dismissing the charges against defendants. Finally, we conclude that, contrary to the

People's contention, defendants Campbell and Bednar had standing to challenge the

validity of the search warrant.

INTRODUCTION

Based upon evidence obtained from a search pursuant to a court-authorized

warrant, the Riverside County District Attorney's Office charged defendants with

possession of marijuana for sale (Health & Saf. Code, I 11359: count 1); transportation

of marijuana ( 11360, subd. (a): count 2); and maintaining a business for the purpose of

selling marijuana ( 11366: count 3).

Defendants brought a motion to quash the search warrant. The court granted the

motion finding (1) the detective who authored the affidavit in support of the search

warrant was not qualified as an expert on the CUA and MMP A; (2) the dispensary the

1 All further statutory references are to the Health and Safety Code unless otherwise

specified.

3

EX. PG.11

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 23 of 109 Page ID #:78

defendants operated qualified as a "primary caregiver" under the CUA and thus they did

not violate the law; and (3) the warrant and resulting evidence were therefore illegal. The

court thereafter dismissed the case based upon a lack of evidence.

The People appeal, asserting the court erred in quashing the search warrant

because (1) the MMP A, which implemented the CUA, unconstitutionally amended the

CUA by authorizing marijuana cooperatives as primary caregivers; (2) the defendants'

storefront dispensary did not qualify as a primary caregiver under the MMPA; (3) the

"collective knowledge" doctrine established probable cause for the warrant; (4) the

detective who authored the search warrant provided competent expert evidence to support

a finding of probable cause; (5) the good faith exception to the exclusionary rules applies

even if the search warrant was invalid; and (6) defendants Bednar and Campbell did not

have standing to challenge the search warrant as they were not owners of CannaHelp.

FACTUALANDPROCEDURALBACKGROUND2

A. The Investigation

In October 2005 Hochanadel opened a marijuana dispensary named "Hempies" in

the City of Palm Desert. Hochanadellater changed the name to "CannaHelp."

Hachanadel filed a certificate of use statement with the State of California, identifying it

as a dispensary for medical marijuana. CannaHelp obtained a business license from the

City of Palm Desert to operate a medical marijuana dispensary and operated it in a

transparent fashion. Access to the business was controlled by employees, who allowed

2 Because this matter was dismissed prior to trial, we take the facts from the

preliminary hearing transcript and the search warrant affidavit.

4

EX. PG.12

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 24 of 109 Page ID #:79

customers to enter a room where their medical marijuana prescription was verified. Once

it was verified the customer had a valid prescription, the customer was allowed access to

a second room where various types of marijuana were on display. Employees received

weekly training on the different strains of marijuana and offered advice to patients on

what strains were effective for different ailments. Prior to making a purchase, customers

completed paperwork designating CannaHelp as their primary caregiver. All the patients

of CannaHelp had valid doctor's statements, and CannaHelp contacted authorities when

someone tried to illegally purchase marijuana. CannaHelp operated like any other

business, with financial records, employee records, and policies and procedures.

Campbell and Bednar were the managers and co-owners of CannaHelp. All three

defendants had medical referrals for marijuana and were qualified medical marijuana

patients under the CUA.

Riverside County Sheriffs Detective Robert Garcia investigated CannaHelp.

Under his direction, police conducted surveillance of CannaHelp. They observed a

significant amount of buying activity. The customers were mostly young, without any

observable health conditions. Detective Garcia saw Gary and Krista Silva arrive in a van.

It was determined Gary Silva was a manufacturer and supplier of marijuana to

CannaHelp.

On March 14, 2006, federal agents executed a search warrant at Gary Silva's

home. While executing the search warrant, officers observed a fully operational growing

operation in a sectioned-off portion of the garage, with 69 marijuana plants and growing

equipment. Agents found "numerous" loaded firearms in Silva's residence. They also

5

EX. PG. 13

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 25 of 109 Page ID #:80

discovered several canisters of dried marijuana for sale, and marijuana on drying racks in

the master bedroom.

Detective Garcia sent an undercover officer into CannaHelp with a manufactured

physician's statement produced by the sheriffs department. That officer was denied entry

when CannaHelp employees could not verify the physician's statement was legitimate.

A second officer then went to a physician in Los Angeles and complained of

chronic back pain. He obtained a statement from that doctor allowing him to purchase

medical marijuana. He presented it to CannaHelp and was allowed to purchase

marijuana. Prior to purchasing the marijuana, he was given advice as to which strain

would be most helpful for his back pain and signed a document designating CannaHelp

as his primary caregiver.

While inside CannaHelp, the undercover agent observed an ATM machine and

three display boards listing prices for different quantities of marijuana. The agent also

observed plastic containers of marijuana inside a glass counter. An employee

recommended a specific type of marijuana for his back pain, and he purchased one ounce

of marijuana for $290. The same agent later conducted another undercover buy, this time

purchasing one-half an ounce for $290.

B. Search Warrant Affidavit

Detective Garcia executed an affidavit in support of a search warrant for

Hochanadel's residences and CannaHelp. Detective Garcia related his experience in

narcotics investigations, noting that he was assigned to the Special Investigations Bureau

charged with narcotics investigations. He stated that during his employment with the

6

EX. PG.14

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 26 of 109 Page ID #:81

Riverside County Sheriff's Department he "participated in several narcotics training and

education courses dealing with the sales, packaging, recognition, preparation,

paraphernalia, and use of narcotics, dangerous drugs and controlled substances. This

training also included instruction of the types of financial records maintained by

persons(s) who traffic in controlled substances." He also "received approximately 20

hours of instruction on narcotics, dangerous drugs, and controlled substances" while

attending the sheriff's academy. He attended an undercover operations course and a

criminal interdiction course. He also detailed his experience in narcotics arrests and

search warrants, as well as investigations of marijuana grow operations.

The affidavit then detailed the investigation of CannaHelp, discussed, ante. Based

upon that investigation, Detective Garcia concluded that CannaHelp was operating

illegally because it was "selling marijuana, which is a violation of [sections] 11359 and

11360. In California, there is no authority for the existence of storefront marijuana

businesses. The [MMP A] allows patients and primary caregivers to grow and cultivate

marijuana, no one else. A primary caregiver is defined as an 'individual' who has

consistently assumed responsibility for the housing, health or safety of a patient. A

storefront marijuana business cannot, under the law, be a primary caregiver." Detective

Garcia further opined CannaHelp was operating illegally because it was a for-profit

enterprise: "Additionally, given this is a 'cash only' business, the presence of an ATM

machine, high prices charged for small amounts of marijuana, it is also my opinion that

this criminal enterprise is 'for profit' which is outside of any of the guidelines in the

medical marijuana exceptions." Specifically, Detective Garcia opined the price for

7

EX. PG.15

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 27 of 109 Page ID #:82

marijuana at CannaHelp was approximately twice the price of "mid-grade" marijuana

available on the streets.

Based upon Detective Garcia's affidavit, the court granted the search warrant.

C. Detective Garcia's Preliminary Hearing Testimony

At the preliminary hearing, Detective Garcia admitted he had no formal training in

medical marijuana laws. He was "must given a pamphlet or some paperwork, just given

the laws just to read over."

He further admitted that based upon his review of CannaHelp's financial records, it

was losing money, with annual revenues of $1.7 million, and expenses of $2.6 million,

not including rent, utilities or other expenses. He admitted the business was "upside

down."

D. Motion To Quash

The defendants brought motions to quash the search warrant. Defendants argued

(1) CannaHelp qualified as a primary caregiver under the CUA and MMPA, and

therefore the motion should be quashed based upon a lack of probable cause; and (2) the

search warrant was invalid as Detective Garcia was not qualified to execute it.

After reading the affidavit in support of the search warrant, the transcript of the

preliminary hearing, and the pleadings in the file, the court granted defendants' motion to

quash. The court first determined Detective Garcia was not qualified to author the search

warrant as he had no training or understanding of medical marijuana laws. The court

further found CannaHelp was a valid primary caregiver. In doing so, the court first noted

Detective Garcia was incorrect in his conclusion it was operating at a profit. The court

8

EX. PG.16

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 28 of 109 Page ID #:83

also noted CannaHelp operated in the open, in compliance with city and state regulations,

and only sold to persons holding legitimate medical marijuana cards. Based upon these

facts, the court found CannaHelp was a "legal primary caregiver" and was in compliance

with the medical marijuana laws. The court thus found there was no probable cause for a

search warrant and granted the motion to quash. The court thereafter dismissed the case

based upon a lack of evidence.

DISCUSSION

I. APPLICABLE AUTHORITY

A. The CUA

The CUA was approved by California voters as Proposition 215 in 1996 and is

codified at section 11362.5. (People v. Trippet (1997) 56 Cal.App.4th 1532, 1546;

People v. Tilehkooh (2003) 113 Cal.App.4th 1433, 1436.) Subdivision (d) of section

11362.5 provides: "Section 11357, relating to the possession of marijuana, and Section

11358, relating to the cultivation of marijuana, shall not apply to a patient, or to a

patient's primary caregiver, who possesses or cultivates marijuana for the personal

medical purposes of the patient upon the written or oral recommendation or approval of a

physician." The CUA directed the Legislature to "implement a plan to provide for the

safe and affordable distribution of marijuana to all patients in medical need of

marijuana." ( 11362.5, subd. (b)(1)(C).)

Under the CUA, a "primary caregiver" is defined as "the individual designated by

the person exempted under this section who has consistently assumed responsibility for

the housing, health, or safety of that person." ( 11362.5, subd. (e).) The California

9

EX. PG.17

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 29 of 109 Page ID #:84

Supreme Court has recently held that to be a primary caregiver under this section, an

individual must show that "he or she (1) consistently provided caregiving, (2)

independent of any assistance in taking medical marijuana, (3) at or before the time he or

she assumed responsibility for assisting with medical marijuana." (People v. Mentch

(2008) 45 Ca1.4th 274,283 (Mentch).) The high court in Mentch concluded that a person

does not qualify as a primary caregiver merely by having a patient designate him or her

as such or by the provision of medical marijuana itself. (Id. at pp. 283-285.) Rather, the

person must show "a caretaking relationship directed at the core survival needs of a

seriously ill patient, not just one single pharmaceutical need." (Id. at p. 286.)

B. TheMMPA

In 2003 the Legislature enacted the MMPA, effective January 1,2004, adding

sections 11362.5 through 11362.83 to the Health and Safety Code. (People v. Wright

(2006) 40 Ca1.4th 81, 93.) The express intent of the Legislature was to: "(1) Clarify the

scope of the application of the [CUA] and facilitate the prompt identification of qualified

patients and their designated primary caregivers in order to avoid unnecessary arrest and

prosecution of these individuals and provide needed guidance to law enforcement

officers. [,-r] (2) Promote uniform and consistent application of the [CUA] among the

counties within the state. [,-r] (3) Enhance the access of patients and caregivers to

medical marijuana through collective, cooperative cultivation projects. [,-r] (c) It is also

the intent of the Legislature to address additional issues that were not included within the

[CUA], and that must be resolved in order to promote the fair and orderly implementation

of the [CUA]." (Stats. 2003, ch. 875, 1, subd. (b)(1)-(3), (c), italics added.) The

10

EX. PG.18

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 30 of 109 Page ID #:85

legislative history further states, "Nothing in [the MA1P A] shall amend or change

Proposition 215, nor prevent patients from providing a defense under Proposition

215 .... The limits set forth in [the MA1PA] only serve to provide immunity from arrest

for patients taking part in the voluntary ID card program, they do not change Section

11362.5 (Proposition 215) .... " (Sen. Rules Com., Off. of Sen. Floor Analyses, analysis

of Sen. Bill No. 420 (2003 Reg. Sess.) as amended Sept. 9,2003. p. 6, italics added.)

Of relevance to this appeal, the MMPA added section 11362.775, which provides:

"Qualified patients, persons with valid identification cards, and the

designated primary caregivers of qualified patients and persons with

identification cards, who associate within the State of California in

order collectively or cooperatively to cultivate marijuana for medical

purposes, shall not solely on the basis of that fact be subject to state

criminal sanctions under Section 11357 [possession of marijuana],

11358 [cultivation of marijuana], 11359 [possession for sale], 11360

[transportation], 11366 [maintaining a place for the sale, giving

away or use of marijuana], 11366.5 [making available premises for

the manufacture, storage or distribution of controlled substances], or

11570 [abatement of nuisance created by premises used for

manufacture, storage or distribution of controlled substance]."

The Court of Appeal in People v. Urziceanu (2005) 132 Cal.App.4th 747, 785

(Urziceanu) noted that "[t]his new law represents a dramatic change in the prohibitions

on the use, distribution, and cultivation of marijuana for persons who are qualified

patients or primary caregivers. . . . Its specific itemization of the marijuana sales law

indicates it contemplates the formation and operation of medicinal marijuana

cooperatives that would receive reimbursement for marijuana and the services provided

in conjunction with the provision of that marijuana."

11

EX. PG. 19

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 31 of 109 Page ID #:86

The MMP A also elaborates on the definition of primary caregiver in the CUA. It

first retains the definition of a primary caregiver contained in the CUA: "the individual,

designated by a qualified patient ... who has consistently assumed responsibility for the

housing, health, or safety of that patient or person .. . . " ( 11362.7, subd. (d).) The

subdivision goes on to provide three examples of persons who would qualify as primary

caregivers under this definition: (1) Owners and operators of clinics or care facilities; (2)

"An individual who has been designated as a primary caregiver by more than one

qualified patient or person with an identification card, if every qualified patient or person

with an identification card who has designated that individual as a primary caregiver

resides in the same city or county as the primary caregiver"; and (3) "An individual who

has been designated as a primary caregiver by a qualified patient or person with an

identification card who resides in a city or county other than that of the primary

caregiver, if the individual has not been designated as a primary caregiver by any other

qualified patient or person with an identification card." ( 11362.7, subd. (d)(1-3).)

The MMP A also specifies that collectives, cooperatives or other groups shall not

profit from the sale of marijuana. ( 11362.765, subd. (a) ["nothing in this section shall

authorize ... any ... group to cultivate or distribute marijuana for profit"].)

C. Attorney General Guidelines

Section 11362.81, subdivision (d) provides: "[T]he Attorney General shall

develop and adopt appropriate guidelines to ensure the security and nondiversion of

marijuana grown for medical use by patients qualified under the [CUA]."

12

EX. PG. 20

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 32 of 109 Page ID #:87

On August 25, 2008, the California Attorney General issued "Guidelines for the

Security and Non-Diversion of Marijuana Grown for Medical Use" (A.G. Guidelines)

<http://ag. ca. gov I cms _ attachments/press/pdfs/n 1601_ medicalmarijuanaguidelines. pdf>

(as of Aug. 5,2009). The A.G. Guidelines' stated purpose is to "(1) ensure that marijuana

grown for medical purposes remains secure and does not find its way to non-patients or

illicit markets, (2) help law enforcement agencies perform their duties effectively and in

accordance with California law, and (3) help patients and primary caregivers understand

how they may cultivate, transport, possess, and use medical marijuana under California

law." (Id. atp. l.)

Several of the guidelines are helpful to our analysis. First, the A.G. Guidelines

reiterate the "consistency" element of the defmition of primary caregiver contained in

both the CUA and MMPA: "Although a 'primary caregiver who consistently grows and

supplies ... medicinal marijuana for a section 1l362.5 patient is serving a health need of

a patient,' someone who merely maintains a source of marijuana does not automatically

become the party 'who has consistently assumed responsibility for the housing, health, or

safety' of that purchaser." (A.G. Guidelines, p. 4.)

Further, the A.G. Guidelines provide a definition of "cooperatives" and

"collectives." A cooperative "must file articles of incorporation with the state and

conduct its business for the mutual benefit of its members. [Citation.] No business may

call itself a 'cooperative' (or 'co-op') unless it is properly organized and registered as such

a corporation under the Corporations or Food and Agriculture Code. [Citation.]

Cooperative corporations are 'democratically controlled and are not organized to make a

l3

EX. PG. 21

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 33 of 109 Page ID #:88

profit for themselves, as such, or for their members, as such, but primarily for their

members as patrons.' [Citation. ]" (Id. at p. 8.) Further, "[c]ooperatives must follow

strict rules on organization, articles, elections, and distributions of earnings, and must

report individual transactions from individual members each year." (Ibid.)

A collective is " 'a business, farm, etc., jointly owned and operated by the

members of a group.' [Citation.]" (A.G Guidelines, supra, at p. 8.) Thus, "a collective

should be an organization that merely facilitates the collaborative efforts of patient and

caregiver members-including the allocation of costs and revenues." (Ibid.) Further, the

A.G. Guidelines opine, "The collective should not purchase marijuana from, or sell to,

non-members; instead, it should only provide a means for facilitating or coordinating

transactions between members." (Ibid.)

The A. G Guidelines further provide guidelines for the lawful operation of

cooperatives and collectives. They must be nonprofit operations. (A.G. Guidelines,

supra, at p. 9.) They may "acquire marijuana only from their constituent members,

because only marijuana grown by a qualified patient or his or her primary caregiver may

be lawfully transported by, or distributed to, other members of a collective or

cooperative .... Nothing allows marijuana to be purchasedfrom outside the collective

or cooperative for distribution to its members. Instead, the cycle should be a closed-

circuit of marijuana cultivation and consumption with no purchases or sales to or from

non-members. To help prevent diversion of medical marijuana to non-medical markets,

collectives and cooperatives should document each member's contribution of labor,

14

EX. PG. 22

Case 8:12-cv-01345-AG-MLG Document 8 Filed 10/03/12 Page 34 of 109 Page ID #:89

resources, or money to the enterprise. They should also track and record the source of

their marijuana." (Id. at p. 10, italics added.)

Distribution and sales to nonmembers is prohibited: "State law allows primary

caregivers to be reimbursed for certain services (including marijuana cultivation), but

nothing allows individuals or groups to sell or distribute marijuana to non-members.

Accordingly, a collective or cooperative may not distribute medical marijuana to any

person who is not a member in good standing of the organization. A dispensing

collective or cooperative may credit its members for marijuana they provide to the

collective, which it then may allocate to other members. [Citation.] Members may also

reimburse the collective or cooperative for marijuana that has been allocated to them.

Any monetary reimbursement that members provide to the collective or cooperative

should only be an amount necessary to cover overhead costs and operating expenses."

(A.G. Guidelines, supra, at p. 10.)

Finally, the A.G. Guidelines provide guidance to law enforcement as to whether

activities comply with the CUA and MMPA. In this regard, the guidelines specifically

address "Storefront Dispensaries." (A.G. Guidelines, supra, at p. 1l.) The Attorney

General is of the opinion that while "dispensaries, as such, are not recognized under the

law," "a properly organized and operated collective or cooperative that dispenses medical