Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Family Matters JOSEPH A. SHEPARD, Husband of Claire McCaskill, Has Seen His Financial Dealings Become The Target of Political Attacks. Now He Talks About Them.

Uploaded by

Darin Reboot CongressOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Family Matters JOSEPH A. SHEPARD, Husband of Claire McCaskill, Has Seen His Financial Dealings Become The Target of Political Attacks. Now He Talks About Them.

Uploaded by

Darin Reboot CongressCopyright:

Available Formats

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri) August 27, 2006 Sunday FOURTH EDITION Family matters JOSEPH A.

SHEPARD, husband of Claire McCaskill, has seen his financial dealings become the target of political attacks. Now he talks about them. BYLINE: By Virginia Young POST-DISPATCH JEFFERSON CITY BUREAU CHIEF SECTION: NEWSWATCH; Pg. B1 LENGTH: 1448 words When an apartment complex for the elderly in Columbia, Mo., was about to go belly-up, the owners called Joseph A. Shepard. Shepard, the husband of Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Claire McCaskill, loves fixing "a busted deal." So he snapped it up. For 30 years, Shepard has used that flair for finance to amass a housing empire that, at one point, included nearly 10,000 apartments in 23 states. Now, those far-flung holdings have given the Missouri Republican Party ammunition against McCaskill in the Nov. 7 election. Party officials have accused her of hiding family assets, taking advantage of government subsidies and conducting audits where she has conflicts of interest. The GOP has filed a complaint with the Senate Ethics Committee, alleging that Shepard's web of 264 interlocking companies is deliberately confusing. Questions revolve around how 175 of his partnerships can be valued at less than $1,000. McCaskill, the state auditor, said she has complied fully with disclosure laws. According to the statement she filed with the Senate, the couple's net worth totals between $13 million and possibly more than $30 million. She said Shepard, whom she married in 2002, is a self-made businessman who has improved housing for poor people. His first project in the Bootheel region in 1976 replaced "shacks, cardboard windows and outhouses." "Has he made money? Yes," she said. "But is there anything he's done that was wrong or illegal or not playing by the rules? No, of course not." Shepard, who avoided reporters when his nursing homes became an issue in McCaskill's unsuccessful bid for governor in 2004, agreed to an in-depth interview with the Post-Dispatch last month. For more than two hours in his white-columned office building in Webster Groves, he answered questions. But he declined to turn over his tax return, as Republicans have demanded. "That's private," he said. McCaskill "argued with me, but I'm not going to do it." While Shepard's fortune provided $1.6 million when McCaskill battled Gov. Bob Holden in 2004 for the Democratic nomination for governor, Shepard doesn't anticipate a similar outlay this time. "It's not like before," he said. "She ought to be able to make it on her own."

Who is Joe Shepard? The picture of Shepard that emerges from public records and interviews reveals a shrewd businessman who has aggressively sought public subsidies and made millions, mainly in rural, low-income housing. In the mid-1980s, he even had a Washington office and traveled there every week to lobby for the Council for Rural Housing and Development. Shepard, 60, said he has been hooked on business since his first accounting class. He attended Principia College, a school for Christian Scientists in Elsah, Ill., about 35 miles from St. Louis. Graduating in 1968, he was briefly a church practitioner, or lay minister, but found "it wasn't my calling." He soon got his first taste of deal-making. Shepard returned to his hometown of East Lansing, Mich., to help salvage his father's Red Wing shoe stores, which were threatened by the debts of a sister business. Moving to St. Louis in 1973, he ran financial projections for developers at an architectural firm, all the while looking for ways to become his own boss. He compares his entrepreneurial drive to a woman knowing she wants to be a mother. "Well, I knew I was going to have my own business," he said. "I do pro formas in my head. The more complicated it is, the more I enjoy it." In 1976, he founded Group Three Construction Co., the firm that would form the backbone of his housing network. But the company got off to a shaky start: One partner immediately died in a plane crash. That left Shepard and partner Skip Mange, now a Republican St. Louis County councilman. "Neither of us had any money," Shepard quipped. Luckily, the federal Farmers Home Administration provided 1 percent loans. Shepard wooed investors while Mange, a civil engineer, supervised construction. Together, the pair developed more than 60 apartment complexes before Mange left the firm. On the mantle in Shepard's office is a photo of the pair at their first groundbreaking -- in impoverished Hayti, Mo. Shepard also served on the board of the Children's Home Society of Missouri, which provides adoption services. He and his first wife, Suzanne Shepard, adopted four children, who now range in age from 24 to 30. How subsidies work Shepard's housing empire eventually stretched across the South and Midwest, from Kissimmee, Fla., and Roanoke, Va., to Sylvan Grove, Kan., and Wilber, Neb. It consists of overlapping partnerships, which are virtually indecipherable to a layperson. Housing experts say there are several reasons for the Byzantine business structures. The government requires a separate limited partnership for each project. Also, developers can sell their tax credits -- but only to buyers who own a share of the development. Diagrams Shepard provided look like spider webs. Take one example -- a 24-unit complex in Howardville, Mo.

Shepard developed the apartments. He also is a shareholder in six entities that have a slice of the project's ownership. However, his stake amounts to less than 4 percent, and third-party investors own the rest. The low-income housing industry is lucrative for rich investors because they can write off more money than a project produces, thus claiming a net loss for tax purposes. That helps explain why Shepard's interest in 175 companies is valued at less than $1,000 in the report McCaskill filed. As for the 192 companies listed as producing less than $201 in annual income, McCaskill's campaign says many of the projects have no return at all because the government controls the rent. Shepard has quit developing apartments and now works mainly as a middleman, selling tax credits. His other businesses include a property management company and three Red Wing shoe stores, including one outside the South County mall. GOP cites conflicts During McCaskill's last campaign, Shepard's six nursing homes drew Republican barbs. They are likely targets again, even though he has sold most of those interests. Republicans say McCaskill misled the public by saying Shepard was out of the business in 2004. Records show he still received $3 million in rent from nursing home companies that year. The GOP says the auditor should have hired an independent firm to audit the regulatory unit that licenses nursing homes. McCaskill contends she has no conflict. Her audit, which is under way, doesn't overlap with any period of time when her husband operated nursing homes, she said. He still owns a building that contains a nursing home in Moberly, Mo. Republicans also say McCaskill shouldn't audit the Missouri Housing Development Commission. They contend Shepard still benefits from subsidies because a Georgia company that bought a Shepard development received a government loan. Shepard laughs at the allegation. "You're telling me I can't even sell them? What should I do? Bomb them?" Shepard's maze of businesses could include an offshore tax shelter, Republicans say. They point to McCaskill's disclosure statement, which lists an interest in the Rural Housing Re-Insurance Co. of America Ltd., located in Bermuda. Bottom line: Republicans want Shepard's tax return. "I believe that's something the public has a right to know," says GOP executive director Jared Craighead. "There are lots of hardworking citizens who make $28,000 a year and pay way too much in income taxes." Shepard says he and other developers created the Bermuda company in 1986 because the property insurance market was tight and apartment projects were unable to secure policies. McCaskill's campaign said he owns less than 6 percent of the company. Still, Shepard's divorce from his first wife suggests that he knows how to hold taxable profits down. The divorce filing, in St. Louis County Circuit Court,

showed that the couple paid no federal income tax in 1995. All that, of course, was before McCaskill knew Shepard. So the political impact is hard to gauge. McCaskill said her husband pays "a significant amount of taxes, oodles and oodles of taxes, now." Some staunch Republicans who know Shepard well say the GOP's claims seem like a stretch. His longtime banker, prominent Republican L.B. Eckelkamp Jr., of Washington, Mo., calls Shepard a "totally honest, reputable businessman." Eckelkamp is chief executive officer of the Bank of Washington. Mange, Shepard's first business partner, said the two have remained friends since Mange sold his interests to Shepard two decades ago. Mange said campaigns should stick to the issues and avoid personal attacks like those being aimed at Shepard. "I'm a Republican, but I find it unfortunate," Mange said.

You might also like

- GUTMAN, H. G. - Slavery and The Numbers Game - A Critique of Time On The CrossDocument204 pagesGUTMAN, H. G. - Slavery and The Numbers Game - A Critique of Time On The CrossMarcos Marinho100% (1)

- Directory Police-Officers 13022019 PDFDocument9 pagesDirectory Police-Officers 13022019 PDFPrabin Brahma0% (1)

- Civics EOC Review Sheet With Answers UPDATEDDocument22 pagesCivics EOC Review Sheet With Answers UPDATEDTylerNo ratings yet

- Termination of Parental Rights Does Not Terminate Child Support - Blog - Schwartz Law FirmDocument3 pagesTermination of Parental Rights Does Not Terminate Child Support - Blog - Schwartz Law FirmVonerNo ratings yet

- Indian Muslims as Diverse and Heterogeneous CommunityDocument85 pagesIndian Muslims as Diverse and Heterogeneous Communitya r karnalkarNo ratings yet

- Democracy Inc.: How Members of Congress Have Cashed In On Their JobsFrom EverandDemocracy Inc.: How Members of Congress Have Cashed In On Their JobsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- DCCC Memo: Democrats On OffenseDocument5 pagesDCCC Memo: Democrats On Offenserobertharding22No ratings yet

- Final Exam - Readings in Philippine History Attempt 2Document17 pagesFinal Exam - Readings in Philippine History Attempt 2RadNo ratings yet

- Bush Bucks: How Public Service and Corporations Helped Make Jeb RichFrom EverandBush Bucks: How Public Service and Corporations Helped Make Jeb RichNo ratings yet

- Volume 42, Issue 28, July 15, 2011Document56 pagesVolume 42, Issue 28, July 15, 2011BladeNo ratings yet

- Korean Slang UpdatesDocument5 pagesKorean Slang UpdatesaaNo ratings yet

- Volume 45, Issue 10, March 7, 2014Document60 pagesVolume 45, Issue 10, March 7, 2014BladeNo ratings yet

- 1.2 Community Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship (CSC) - Compendium of DLPs - Class FDocument109 pages1.2 Community Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship (CSC) - Compendium of DLPs - Class FJohnLesterDeLeon67% (3)

- BANAT V COMELECDocument3 pagesBANAT V COMELECStef MacapagalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 Self-TestDocument9 pagesChapter 22 Self-TestDaniel BaoNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Constitution Volume I Reviewer MidtermsDocument17 pagesNotes On The Constitution Volume I Reviewer MidtermsHannah Plamiano TomeNo ratings yet

- Fujiki vs. Marinay Case DigestDocument1 pageFujiki vs. Marinay Case DigestRab Thomas Bartolome100% (4)

- Henrietta Lacks' immortal cells changed medicineDocument5 pagesHenrietta Lacks' immortal cells changed medicineAakash ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Democracy Fix: How to Win the Fight for Fair Rules, Fair Courts, and Fair ElectionsFrom EverandThe Democracy Fix: How to Win the Fight for Fair Rules, Fair Courts, and Fair ElectionsNo ratings yet

- Letters Fo Hazrat UmarDocument6 pagesLetters Fo Hazrat UmarIbrahim BajwaNo ratings yet

- Post-Dispatch: Joseph Shepard ProfileDocument5 pagesPost-Dispatch: Joseph Shepard ProfileRebecca BergNo ratings yet

- New York Times Article - Exhibit BDocument5 pagesNew York Times Article - Exhibit BDavid LombardoNo ratings yet

- North Suburban Republican Forum: You'll Be Able To Hear From Followed by CD-7 Candidate Joe CoorsDocument23 pagesNorth Suburban Republican Forum: You'll Be Able To Hear From Followed by CD-7 Candidate Joe CoorsThe ForumNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 07-19-2013Document36 pagesTimes Leader 07-19-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Who Is Greg LindbergDocument3 pagesWho Is Greg LindbergGeorge FinchNo ratings yet

- 121116Document52 pages121116BladeNo ratings yet

- Lembo Locks Up The Nerd Vote - CT Mirror 5-31-10Document3 pagesLembo Locks Up The Nerd Vote - CT Mirror 5-31-10jkozin1488No ratings yet

- 03-01-2012 EditionDocument28 pages03-01-2012 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 03-24-2013Document83 pagesTimes Leader 03-24-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- The Real Deal Press - Vol 1 # 12 - March 2015Document12 pagesThe Real Deal Press - Vol 1 # 12 - March 2015RTAndrewsNo ratings yet

- March 2012 NaysayerDocument1 pageMarch 2012 NaysayerdenverhistoryNo ratings yet

- County Asks State For Jail Cash: The Underdog of Digital DealsDocument28 pagesCounty Asks State For Jail Cash: The Underdog of Digital DealsSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Funding Quirk Shields Community Colleges From CutsDocument32 pagesFunding Quirk Shields Community Colleges From CutsSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Intro Gov Journal Entry 2Document3 pagesIntro Gov Journal Entry 2api-303156849No ratings yet

- Volume 44, Issue 1 - January 4, 2012Document40 pagesVolume 44, Issue 1 - January 4, 2012BladeNo ratings yet

- Inquirer Pennsylvania House Control at Stake TuesdayDocument2 pagesInquirer Pennsylvania House Control at Stake TuesdayRock QuarryNo ratings yet

- Volume 42, Issue 42 - October 21, 2011Document56 pagesVolume 42, Issue 42 - October 21, 2011BladeNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 05-30-2012Document42 pagesTimes Leader 05-30-2012The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Summary of Dark Money: by Jane Mayer | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Dark Money: by Jane Mayer | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Street Hype Newspaper - Nov 19-30, 2011 IssueDocument24 pagesStreet Hype Newspaper - Nov 19-30, 2011 IssuePatrick MaitlandNo ratings yet

- The Swing Vote The Untapped Power of IndependentsDocument12 pagesThe Swing Vote The Untapped Power of IndependentsMacmillan PublishersNo ratings yet

- June 13, 2013 Send Tips To or - Follow The Latest Developments atDocument13 pagesJune 13, 2013 Send Tips To or - Follow The Latest Developments atCWALocal1022No ratings yet

- 02-03-08 WP-Retirements From House Adding Up by Paul KaneDocument3 pages02-03-08 WP-Retirements From House Adding Up by Paul KaneMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- Volume 43, Issue 49 - December 7, 2012Document56 pagesVolume 43, Issue 49 - December 7, 2012BladeNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 10-11-2012Document46 pagesTimes Leader 10-11-2012The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- NY Gay Marriage ArticleDocument9 pagesNY Gay Marriage ArticleareedadesNo ratings yet

- 14-10-11 As Herman Cain Surges, Corporate Media Ignore His Koch ConnectionsDocument5 pages14-10-11 As Herman Cain Surges, Corporate Media Ignore His Koch ConnectionsWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- SyppaperDocument24 pagesSyppaperapi-254348257No ratings yet

- Volume 45, Issue 5, January 31, 2014Document39 pagesVolume 45, Issue 5, January 31, 2014BladeNo ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel For August 27, 2012Document8 pagesThe Daily Tar Heel For August 27, 2012The Daily Tar HeelNo ratings yet

- April 1, 2012Document2 pagesApril 1, 2012Chicago Sun-TimesNo ratings yet

- Rival Developer Blew WhistleDocument12 pagesRival Developer Blew WhistleReese DunklinNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 09-04-2013Document34 pagesTimes Leader 09-04-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 09-21-2013Document42 pagesTimes Leader 09-21-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Summary: Millionaire Republican: Review and Analysis of Wayne Allyn Root's BookFrom EverandSummary: Millionaire Republican: Review and Analysis of Wayne Allyn Root's BookNo ratings yet

- 01-19-12 EditionDocument28 pages01-19-12 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Personal InformationDocument7 pagesPersonal Informationapi-127658921No ratings yet

- Times Leader 02-15-2012Document38 pagesTimes Leader 02-15-2012The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Ranking The Mayoral Candidates - EthicsDocument1 pageRanking The Mayoral Candidates - EthicssaywhatuserNo ratings yet

- Volume 43, Issue 31 - August 3, 2012Document40 pagesVolume 43, Issue 31 - August 3, 2012BladeNo ratings yet

- Letters From Foreclosure HellDocument6 pagesLetters From Foreclosure Hell83jjmackNo ratings yet

- North Suburban Republican Forum: Making A Difference For Myself, My Business, My Industry, My CountryDocument15 pagesNorth Suburban Republican Forum: Making A Difference For Myself, My Business, My Industry, My CountryThe ForumNo ratings yet

- The Toxic TycoonDocument13 pagesThe Toxic Tycoonapi-207653909No ratings yet

- Summary: The Conscience of a Libertarian: Review and Analysis of Wayne Allyn Root's BookFrom EverandSummary: The Conscience of a Libertarian: Review and Analysis of Wayne Allyn Root's BookNo ratings yet

- Download Politics At Work How Companies Turn Their Workers Into Lobbyists 1St Edition Alexander Hertel Fernandez all chapterDocument49 pagesDownload Politics At Work How Companies Turn Their Workers Into Lobbyists 1St Edition Alexander Hertel Fernandez all chapterwilliam.charles664100% (4)

- Steve Jacobs BioDocument3 pagesSteve Jacobs Bioapi-236545094No ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1Document9 pagesReading Passage 1Kaushik RayNo ratings yet

- AD Iver Nion AD Iver NionDocument17 pagesAD Iver Nion AD Iver NionMad River UnionNo ratings yet

- March 14, 2008 News JournalDocument1 pageMarch 14, 2008 News JournalMNCOOhioNo ratings yet

- 03-18-14 EditionDocument28 pages03-18-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Ch9 Models WG1AR5 SOD Ch09 All FinalDocument218 pagesCh9 Models WG1AR5 SOD Ch09 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- SummaryForPolicymakers WG1AR5-SPM FOD FinalDocument26 pagesSummaryForPolicymakers WG1AR5-SPM FOD FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch8 Supplement WG1AR5 SOD Ch08 SM FinalDocument13 pagesCh8 Supplement WG1AR5 SOD Ch08 SM FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- TechnicalSummary WG1AR5-TS FOD All FinalDocument99 pagesTechnicalSummary WG1AR5-TS FOD All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch7 Clouds-Aerosols WG1AR5 SOD Ch07 All FinalDocument139 pagesCh7 Clouds-Aerosols WG1AR5 SOD Ch07 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch2 Obs-Atmosur WG1AR5 SOD Ch02 All FinalDocument190 pagesCh2 Obs-Atmosur WG1AR5 SOD Ch02 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch5 Paleo WG1AR5 SOD Ch05 All Final PDFDocument131 pagesCh5 Paleo WG1AR5 SOD Ch05 All Final PDFDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch6 Carbonbio WG1AR5 SOD Ch06 All FinalDocument166 pagesCh6 Carbonbio WG1AR5 SOD Ch06 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch14 Supplement WG1AR5 SOD Ch14 SM FinalDocument21 pagesCh14 Supplement WG1AR5 SOD Ch14 SM FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch8 Radiative-Forcing WG1AR5 SOD Ch08 All FinalDocument124 pagesCh8 Radiative-Forcing WG1AR5 SOD Ch08 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch3 Obs-Oceans WG1AR5 SOD Ch03 All FinalDocument89 pagesCh3 Obs-Oceans WG1AR5 SOD Ch03 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch4 Obs-Cryo WG1AR5 SOD Ch04 All FinalDocument98 pagesCh4 Obs-Cryo WG1AR5 SOD Ch04 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch14 Future-Regional WG1AR5 SOD Ch14 All FinalDocument206 pagesCh14 Future-Regional WG1AR5 SOD Ch14 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch10 Attribution WG1AR5 SOD Ch10 All FinalDocument131 pagesCh10 Attribution WG1AR5 SOD Ch10 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch12 Long-Term WG1AR5 SOD Ch12 All FinalDocument158 pagesCh12 Long-Term WG1AR5 SOD Ch12 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch11 Near-Term WG1AR5 SOD Ch11 All FinalDocument129 pagesCh11 Near-Term WG1AR5 SOD Ch11 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

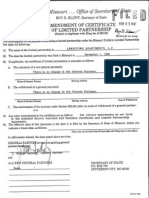

- Lewistown Apartments LPDocument12 pagesLewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch13 Sea-Level WG1AR5 SOD Ch13 All FinalDocument110 pagesCh13 Sea-Level WG1AR5 SOD Ch13 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Final Letter MandamusDocument21 pagesFinal Letter MandamusDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- CEI Appeal EPA Richard Windsor FOIADocument12 pagesCEI Appeal EPA Richard Windsor FOIADarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Ch1-Introduction WG1AR5 SOD Ch01 All FinalDocument55 pagesCh1-Introduction WG1AR5 SOD Ch01 All FinalDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Lewistown Apartments LPDocument3 pagesLewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Lewistown Apartments LPDocument14 pagesLewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- FOIA EPA Email ExchangeDocument3 pagesFOIA EPA Email ExchangeDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- 20061116-2 Lewistown Apartments LPDocument3 pages20061116-2 Lewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Lewistown Apartments LPDocument3 pagesLewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- 20061116-1 Lewistown Apartments LPDocument3 pages20061116-1 Lewistown Apartments LPDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Registered Agent Webster Agency, Inc.Document2 pagesRegistered Agent Webster Agency, Inc.Darin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Report Webster Agency IncDocument1 pageReport Webster Agency IncDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Report Webster Agency IncDocument1 pageReport Webster Agency IncDarin Reboot CongressNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of ARISTOTLEDocument17 pagesPhilosophy of ARISTOTLEYousuf KhanNo ratings yet

- Israel and Chemical-Biological Weapons: History, Deterrence, and Arms ControlDocument27 pagesIsrael and Chemical-Biological Weapons: History, Deterrence, and Arms ControlCEInquiryNo ratings yet

- Foundation ClassDocument8 pagesFoundation ClassnzinahoraNo ratings yet

- Indian Place Name Change ProposalDocument4 pagesIndian Place Name Change ProposalFrank Waabu O'Brien (Dr. Francis J. O'Brien Jr.)100% (1)

- International NegotiationREADING 4,5,6Document30 pagesInternational NegotiationREADING 4,5,6Scarley Ramirez LauriNo ratings yet

- Driving Miss Daisy SGDocument3 pagesDriving Miss Daisy SGharry.graserNo ratings yet

- Dano v. COMELECDocument2 pagesDano v. COMELECneil peirceNo ratings yet

- Alice Through The Working Class by Steve McCaffery Book PreviewDocument25 pagesAlice Through The Working Class by Steve McCaffery Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]No ratings yet

- Task 2 Comparing - Oscar - Salas - Guardia - Group - 30Document7 pagesTask 2 Comparing - Oscar - Salas - Guardia - Group - 30oscar salasNo ratings yet

- Case Study On LeadershipDocument14 pagesCase Study On LeadershipBhuvnesh Kumar ManglaNo ratings yet

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Joseph Stalin Vladimir Lenin Bolshevik RevolutionDocument11 pagesAleksandr Solzhenitsyn Joseph Stalin Vladimir Lenin Bolshevik RevolutionMythology212No ratings yet

- A Study of Estonian Migrants in FinlandDocument38 pagesA Study of Estonian Migrants in Finlandjuan martiNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Early Maliki Law - Ibn Abd Al-Hakam and His Major Compendium of JurisprudenceDocument8 pagesBook Review - Early Maliki Law - Ibn Abd Al-Hakam and His Major Compendium of JurisprudenceIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Mapping and Analysis of Efforts To Counter Information Pollution PDFDocument48 pagesMapping and Analysis of Efforts To Counter Information Pollution PDFAhmad Ridzalman JamalNo ratings yet

- Rothbard 1977 Toward A Strategy For Libertarian Social Change - TextDocument181 pagesRothbard 1977 Toward A Strategy For Libertarian Social Change - TextDerick FernandesNo ratings yet

- CV Hyejin YoonDocument3 pagesCV Hyejin Yoonapi-370360557No ratings yet