Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Influence in The Legislature

Uploaded by

Eric AskinsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Influence in The Legislature

Uploaded by

Eric AskinsCopyright:

Available Formats

JPART 22:347371

Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

Jill Nicholson-Crotty,* Susan M. Miller

*University of Missouri; Oklahoma State University

ABSTRACT

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

An extensive literature explores the correlates of bureaucratic inuence in the implementation of public policy. Considerably less work, however, has investigated the conditions under which bureaucratic actors inuence legislative outcomes. In this article, we develop the argument that effectiveness should be a key determinant of bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process and identify a set of institutional characteristics that may facilitate or constrain this relationship. We test these expectations in an analysis of legislator perceptions of bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes in the 50 US states. The results suggest that the impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on the inuence of the bureaucracy over legislative outcomes is greater in states with legislative term limits, united governments, and fragmented executive branches.

For as long as bureaucratic actors have been recognized as important players in the governance process, rather than simply passive administrators of existing law, scholars have searched for the sources of bureaucratic power in both the administrative process (i.e., policy implementation) (see Meier and Bohte 2007; Rourke 1984) and the legislative process (i.e., policy formulation) (see Carpenter 2001; Krause 1996). The former question has generated a large, well-developed literature, and scholars have thoroughly investigated how the exercise of discretionary authority by bureaucrats inuences policy implementation. The latter subject, however, has received considerably less attention (see Carpenter 2001; Nicholson-Crotty 2009; Christensen, Goerdel, and Nicholson-Crotty 2011), and there is still a great deal we do not know about the ways in which bureaucratic actors inuence policy formulation in the legislative branch. In this article, we address this question. The identied sources of bureaucratic inuence vary widely, particularly in the implementation literature, and include both internal factors, such as expertise and cohesion, and external factors, such as client support and the relative preference positions of other institutional actors (see Meier 2000 for a review). Recent work in this area has emphasized effectiveness as a potential source of bureaucratic inuence over both the administrative process

Address correspondence to the author at nicholsoncrottyj@missouri.edu.

doi:10.1093/jopart/mur054 Advance Access publication on August 22, 2011 The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Inc. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

348

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

and the legislative process (see, e.g., Carpenter 2001).1 In terms of inuence in the legislative process, this approach suggests that when agencies are perceived as competent policy implementers, they can often parlay that reputation into inuence over the development of public policy. Given that the widespread performance and results-oriented management reforms of recent decades are explicitly targeted at making bureaucracies more effective, we nd this assertion particularly interesting. In this sense, these types of reforms, which have sometimes been intended as a means of controlling bureaucratic action (Carroll 1995), may have increased the power that the institution exercises in the legislative process. The impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes is the focus of our inquiry. We test the relationship between bureaucratic effectiveness and inuence in the legislative process in an analysis of the US states. Specically, we assess the impact of the Maxwell Schools Government Performance Project (GPP) measure, which we suggest is a good indicator of perceived bureaucratic effectiveness (or reputation for effectiveness), on state legislator perceptions of bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes. We also examine how other factors, particularly legislative term limits, divided government, and executive fragmentation, condition the impact of perceived effectiveness on perceived inuence over legislative outcomes. With this project, we contribute to the literature by exploring bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process, which has received far less attention than bureaucratic inuence in the implementation process. Moreover, by investigating the interactive effect of bureaucratic effectiveness and other factors on the inuence of the bureaucracy in legislative policy development, we outline conditions under which the impact of effectiveness is enhanced, providing a deeper understanding of the relationship of effectiveness and inuence. This project also highlights the potential link between reform and bureaucratic inuence. In recent decades, administrative reforms have become ubiquitous in state governments, and many of these reforms aim to improve bureaucratic operations. These efforts may augment the role of bureaucratic actors in the legislative process. The essay proceeds in three sections. The rst reviews the relatively limited literature on bureaucratic inuence over legislative policy formulation, highlighting recent work on the importance of effectiveness, and lays out our expectations. The next section provides detailed information about the data, variables, and methods employed in our statistical tests of the relationship between effectiveness and bureaucratic inuence over legislative policymaking. Finally, we discuss the results of those tests and draw some conclusions.

PREVIOUS WORK ON BUREAUCRATIC INFLUENCE IN POLICY FORMULATION

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

The relationship between the politics and administration of public policy is a key question in the study of public administration and democratic theory. The tension (real or perceived) between the ambitions of elected and nonelected ofcials in democratic systems has long created anxiety about the relative power that these actors enjoy in policymaking and inspired volumes of literature (see Stivers 2001 for a partial review). Authors interested in the politics/administration nexus have used power, inuence, and autonomy (often

1 For simplicity, we make a distinction between policy implementation and legislative policy formulation. When we refer to policy formulation, we are strictly referring to the role of bureaucratic actors in determining legislative policy outcomes. We acknowledge that bureaucratic actors play other roles in policy formulation, such as their rulemaking function.

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

349

interchangeably) to describe the bureaucratic inuence over legislative and administrative outcomes. For example, Meier and Bohte (2007, 14) focus on administrative power, dening it as the ability of a bureaucracy to allocate scarce societal resources. Alternatively, Carpenter (2001, 4) explores bureaucratic autonomy, which he denes as bureaucrats . . . securing the policies that they favor despite the opposition of the most powerful politicians. This focuses on self-determined authority over policy outcomes. Although distinct, both denitions point to the active role of the bureaucracy in determining who gets what, when, and how (Lasswell 1936). In this article, we consider perceived bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes, which we view as a reection of one (or perhaps a few) dimension(s) of bureaucratic power. There have been many different conceptions of power and articulations of the faces of power (see Bachrach and Baratz 1962; Dahl 1961; Dahl and Lindbloom 1953; Lukes 1974). Recently, Carpenter (2010) lays out three facets of regulatory powergatekeeping, conceptual, and directive. The inuence that bureaucrats have over legislative outcomes draws on all three. Gatekeeping power, which is the power to establish the agendas and debates that structure human activity, in this context involves bureaucrats setting the legislative agenda by calling attention to problems and inuencing where legislators devote their time. This type of power also entails an anticipatory element in which legislators may decide to disregard an issue out of concern for the reaction of bureaucrats (see Friedrich 1941; Simon 1953). Conceptual power in this setting involves shaping the concepts and vocabularies employed in legislative discussions and supplying the methods of analysis that legislators use to learn about policy problems. This type of power may be based on conscious or unconscious decisions of the bureaucracy that shape fundamental patterns of thought surrounding an issue (Carpenter 2010, 64). Finally, in some instances, bureaucrats use directive power to sway the give-and-take of legislative enactment and get legislators to do something that they would not otherwise do (see Carpenter 2001). Directive power is the traditional notion of power in which A can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do (Dahl 1957, 2023). These three facets are, as Carpenter (2010) notes, interrelated and overlapping. Bureaucratic inuence (perceived or objective) over legislative outcomes is a reection of one or all of these different kinds of power and indicates bureaucratic actors ability to mold, either directly or indirectly, the negotiations surrounding legislation. We specically focus on perceived inuence over legislative outcomes, which is an indication of the extent to which legislators think bureaucrats exercise these different facets of power and bureaucratic actors reputation for molding legislative results. An extensive literature explores bureaucratic power and inuence. A large portion of this research is devoted to evaluating bureaucratic power and/or inuence in policy implementation (e.g., see Hedge, Menzel, and Krause 1989; Khademian 1992; Maynard-Mooney 1989; Meier and Bohte 2007; Rourke 1984; Romzek 1985). Scholars have linked numerous factors, such as policy expertise, bureaucratic effectiveness, employee motivation, and the support of clientele groups and the public, to bureaucratic power over administrative processes. There is also scholarship considering, in a broad sense, bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process. For example, there have been numerous theoretical and case-based studies that suggest that expertise and the resultant information asymmetries allow bureaucratic careerists to have meaningful inuence over certain policies (see, e.g., Durant 1991; Wilson 1989; though see Rourke 1991 for the argument that this power is dwindling). Recent work also indicates the important role that bureaucrats play in legislative hearings, which could lead

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

350

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

to inuence over policy through problem denition and legislative agenda setting (Miller 2004, 2007; May, Sapotichne, and Workman 2009). Additionally, isolated pieces of research demonstrate that bureaucratic actors attempt to inuence legislative behavior (see, e.g., Freeman 1958; Lee 2001). However, research that directly addresses the question of bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes is rare (see Nicholson-Crotty 2009; Christensen, Goerdel, and Nicholson-Crotty 2010). The following section briey reviews this scholarship, paying special attention to studies, theoretical and empirical, that emphasize the importance of bureaucratic effectiveness. The literature on council-manager governments in US municipalities makes important contributions to our understanding of the role of appointed ofcials in determining policy outcomes. Regarding role perception, Nalbandian (1999) nds signicant support for the idea that city managers perceive themselves participants in the policy development process, not as neutral policy implementers. Further, in some municipalities, there is evidence that city managers wield greater political power and are able to have more inuence than elected city council members (Svara 1990). This bureaucratic inuence is traced to the relatively long tenures of city managers and their community support, which is reminiscent of claims regarding the role of expertise and clientele and public support in generating bureaucratic power in the policy implementation literature. Inasimilarvein,theroleofpolicyanalystsinthelegislativeprocesshasalsobeenexplored.In the Canadian provinces, Howlett and Newman (2010) nd that provincial analysts are less experienced and have less training in formal policy analytical techniques than their national counterparts, which they suggest has signicant implications for their ability to inuence policy deliberations in the direction of enhanced evidence-based policy-making (133). The notion that more effective, experienced bureaucratic policy analysts are more inuential in the policymaking process comports well with the argument that general bureaucrats who are more competent have greater legislative inuence. Comparably, in a study of the US states, Hird (2005a, 2005b) nds that based on the perceptions of legislators, larger, more analytical nonpartisan research organizations have signicantly more inuence over policymaking than smaller, more descriptive organizations. He also nds that legislators from states with larger, moreanalyticalnonpartisanresearchorganizationsviewtheseorganizationstohaveapositive impact on their access to quality information for policymaking. Taken together, these ndings indicate a link between the effectiveness of larger, more analytical nonpartisan research organizations(i.e., theirprovision ofgood policymakinginformation) andtheir inuenceover policymaking. City managers and policy analysts are, admittedly, somewhat atypical bureaucrats. However, a limited number of scholars studying bureaucratic actors more generally have also addressed the question of bureaucratic inuence over legislative policy outcomes. These approaches often combine the internal and external sources of power in the implementation process into relatively comprehensive models of inuence over policy formulation in the legislative realm. Krause (1996, 1999, 12) builds his argument on the assertion that:

existing models of bureaucracy tacitly assume that political preferences may inuence agency activity, but that the opposite possibility does not exist. Such an assumption . . . is tenuous at best given what has been established about how public policy is created.

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

As an alternative, he argues for a reciprocal relationship between bureaucrats and policy makers. More specically, he suggests that the expertise of bureaucracies allows them to

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

351

innovate, mobilize interests in support of those innovations, and force other political actors to adapt their positions in response to that support. This adaptation brings the expressed preferences of political principals in line with those of the agents. Thus, bureaucracies are able to inuence policy development by compelling other political actors to adjust their positions and adopt those of the agency. Carpenter (2001) takes a similar approach but adds the concept of bureaucratic effectiveness to his explanation of agency inuence in the formulation of policy. He suggests that the power of bureaucracies is forged politically and that with established reputations for effectiveness bureaucracies can develop the independent power and autonomy to inuence legislative policy formulation. According to Carpenter, bureaucracies build reputations for effective performances that help them assemble supportive coalitions, which, in turn, lead to political inuence. In this conception, bureaucracies attain power by performing well and networking with actors in the environment in order to build coalitions of esteem. For our purposes, the most important aspect of Carpenters (2001) work is the signicance it affords a bureaucracys reputation for effectiveness in the development and exercise of bureaucratic power. In his story, agencies are able to pursue the policies they prefer in large part because they have proven themselves to be effective managers of policies that citizens and elected ofcials value. The argument that inuence is a product of constituent relationships that result from bureaucratic competence accords well with other work on bureaucratic involvement in the policy process. Clarke and McCool (1996) argue that successful natural resource agencies are able to inuence policy, including the issues considered and ultimately adopted by Congress, when they maintain control over valued information or expertise and develop relationships with important groups. As a specic example, they highlight the Forest Services recruitment and mobilization of clientele following the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 as an explanation for the agencys inuence over the outcomes mandated in the 1976 Forest Management Act. More generally, they suggest that organizations like the Forest Service and the Army Corps of Engineers were able to use constituency relationships to become and remain important players in the policy subsystem, which enabled them to work effectively in the subsystem to produce outputs close to their preferences.

THE CONDITIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EFFECTIVENESS AND LEGISLATIVE INFLUENCE

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

The literature discussed above suggests that under certain circumstances, bureaucratic actors may have inuence on legislative outcomes, particularly when they can build support among important constituencies by being competent implementers of policy or being seen as the predominant experts in a given issue area. Carpenter (2001) suggests that politicians may be compelled to accept bureaucratic policy innovation in the face of sufcient interest group pressure. Even in less extreme cases, it is relatively easy to imagine the mechanism by which effectiveness may translate into legislative inuence for bureaucratic actors. That mechanism rests heavily on the two primary motivations of legislatorsreelection and good public policy (Mayhew 1974). If we begin with the assumption that the behavior

352

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

of state legislators is driven by these desires, then it follows that they need information to decide which policy alternatives will be most popular and/or will produce the greatest net benet for their constituents.2 Work on the linkage between bureaucratic expertise and policy inuence speaks to the latter element, with legislators turning to experts in the bureaucracy for details about policy costs and benets (Clarke and McCool 1996; Krause 1996, 1999). Likewise, the relationships that bureaucracies cultivate with important constituencies allow them to provide legislators information about the former. Bureaucracies garner support from groups in society because those groups share similar preferences regarding policy outcomes and think that the agency effectively produces those outcomes. The greater number of these relationships an agency has with important groups the more legitimate it will appear when arguing that its preferred policy is also the preferred policy of key legislative constituencies. In other words, bureaucracies viewed as effective implementers and/or as valued repositories of expertise should nd it easier to convince legislators that they not only know which policies are technically superior but also those that hold the greatest political advantage. Thus, effective bureaucracies should have more inuence in the legislative process (Hypothesis 1). The discussion thus far also suggests, however, that the relationship between effectiveness and inuence might be moderated by the needs of legislators. More precisely, we expect that the capacity of legislators to gather their own information regarding the merit and popularity of policy alternatives, as well the structural relationship between the legislature and executive within each state (which may inuence the willingness to trust bureaucratic advice) will determine the degree to which bureaucratic effectiveness translates into inuence. Research suggests two legislative characteristics that may inuence the ability of legislators to gather and utilize policy relevant information. First, scholars argue that legislative term limits reduce expertise, institutional memory, and the ability of lawmakers to craft effective solutions to complex problems. Instead of learning the intricacies of various policy areas, term limits force legislators to rely more heavily on outside experts, such as bureaucrats, lobbyists, and legislative staff, for policy information (Berman 2004; Cain and Kousser 2004; Carey et al. 2006; Moncrief and Thompson 2001; Mooney 2007; Sarbaugh-Thompson et al. 2004; Straayer and Bowser 2004). Second, research suggests that legislative professionalization, typically proxied with some combination of compensation, staff, session length, and institutional expenditures, determines the ability of legislators to gather policy relevant information and bring expertise and focus to the policymaking process (Mooney 1994; see also Bowman and Kearney 1986; Squire 1992). In states with highly competent bureaucracies, legislators with limited ability to gather policy relevant information due to the presence of term limits or low levels professionalization may choose to take policy advice from bureaucrats more often, giving them greater inuence over the development of policy. We expect, therefore, that effective bureaucracies will be able to exercise greater inuence in the lawmaking process in states with term limits or low levels of professionalization because the policy solutions that the bureaucratic actors offer are likely to be more unique, sophisticated, or sound relative to those of the legislature (Hypotheses 2 and 3).

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

2 This is the premise for informational models of interest group inuence over legislation (see, e.g., Austen-Smith 1997).

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

353

Our storyalsosuggeststhat theinuence ofbureaucraticactorsover legislative outcomes depends in part on their ability to foster alliances with a diverse and/or important set of political actors. Previous research suggests that bureaucrats are better able to build these relationships when they have discretion over the implementation of policy and the ability to innovate (see Carpenter 2001; Clark and McCool 1996). The separation of powers literature, which envisions a zone between political principals in which bureaucracies exercise discretion, leads to the expectation that divided government increases bureaucratic discretion because of the large distance between political principals with divergent preferences (see Hammond and Knott 1996; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast 1987). Thus, we expect that governments controlled by more than one party are likely to allow effective bureaucracies more discretion over implementation and room to innovate policy solutions and, thus, a greater ability to garner support from important constituencies. This, in turn, should provide greater leverage when bureaucratic actors attempt to inuence legislation. Therefore, we expect that effective bureaucracies will exercise more inuence in states where different political parties control the major governing institutions (Hypothesis 4). Finally, fragmentation in the executive branch may also enhance the relationship between effectiveness and bureaucratic inuence in determining legislative outcomes. States vary greatly in the number of separately elected ofcials who serve in the executive branch. In some states, such as Maine and New Hampshire, the governor (or governor/ lieutenant governor team) is the only elected ofcial in the executive branch, and she appoints the other positions. However, in other states, such as California and North Carolina, other major executive ofcials, such as the heads of the agriculture department and the education department, are also elected directly by the people (Beyle and Ferguson 2008). This difference has important implications for the power of the governor and the operation of state governments (Beyle 1995; Robinson 1998) and may condition the relationship between bureaucratic effectiveness and the impact of bureaucrats in legislative policy formulation.3 When the executive is consolidated and the governor and agency heads are working as a collective whole, the effectiveness of the bureaucracy may not be a signicant source of bureaucratic inuence over legislative policy outcomes. Under these circumstances, because the whole executive branch may be viewed as an extension of the governors ofce, other factors, such as shared partisanship between the governor and the legislative branches, may be more important for bureaucratic inuence over legislative policy formulation. However, when the executive is fragmented and the governor and agency heads have individual agendas, the effectiveness of the bureaucracy may be an important determinant of bureaucratic inuence. Under these circumstances, the bureaucracy will be viewed less as an extension of the governors ofce and more as an independent actor, and in order to gain inuence over legislative policy development, bureaucratic agencies and their ofcials will need to demonstrate competence in their own right and earn the condence of legislators. Thus, we expect that effectiveness will have a greater positive impact on the inuence of the bureaucracy over legislative outcomes in states with fragmented executives (Hypothesis 5).

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

3 See Berry and Gersen (2008) for more information about plural executives in the US states and an argument that an unbundled executive is ultimately more effective.

354

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

TESTING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EFFECTIVENESS AND POWER Data

To test the expectation that effectiveness leads to greater inuence over policy formulation for bureaucracies, we use state legislators perceptions of bureaucratic inuence on legislative outcomes that come from the 2002 State Legislative Survey (Carey et al. 2002). These data offer an ideal opportunity to test our hypotheses. The broader literature on interest groups has long acknowledged the difculty of identifying the actual inuence that various groups have over the decisions of elected representatives and, ultimately, over policy (see Smith 1995 for a review). Rather than look for a relationship between bureaucratic effectiveness and policy differences across the states, which would force us to contend with the myriad alternative causes and counterfactuals that accompany such an approach, the state legislator data discussed above allow us to ask lawmakers directly about the inuence that bureaucrats exert over policy formulation. The 2002 State Legislative Survey is a stratied random sample of state legislators within all 50 states. The data contain responses from 2,982 legislators, which represent a response rate of 40.1%. This is relatively standard for surveys of state legislators (Maestas, Neeley, and Richardson 2003). The survey was originally designed to evaluate the potential compositional, behavioral, and institutional effects of term limits.4 It contains information about the legislators campaigns and elections, their districts, their views on different aspects of the legislative process in their chambers, their legislative behavior, and demographic information. The data are weighted in order to correct for differences in response probability on variety of factors.5 We use the restricted-use version of the data, which includes state identiers and allows us to match state characteristics to individual legislator responses. The sources for the data on state characteristics are discussed below.

Dependent Variable

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

The dependent variable in subsequent analysis represents the perceptions of legislators regarding the inuence of bureaucratic actors in developing policy. This variable is created from legislator responses to the question What do you think is the relative inuence of the following actors in determining legislative outcomes in your chamber? We model responses regarding Bureaucrats/Civil servants. Potential responses range from 1 for No Inuence to 7 for Dictates Policy. This question allows us to capture the perceived inuence of bureaucrats in legislative policy formulation. This measure captures how bureaucratic actors participate in inuencing the interplay surrounding legislative enactment, instead of bureaucratic inuence over policy formulation in the broadest sense. This is an important distinction and allows us to test the impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on the give-and-take of legislative policy development. Unfortunately, this measure does not differentiate between the disparate types or degree of inuence that different agencies possess and instead captures the general inuence of the entire state bureaucracy. This general measure enables us to test our hypotheses but leaves questions concerning specic types of inuence open for additional research. The mean response is 3.35 with a standard deviation of 1.23. The complete descriptive statistics for these and other variables are listed in table 1.

4 5

For more information about the 2002 State Legislative Survey, see Carey et al. (2006). These include chamber, session length, gender of the legislator, district size, and region.

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

355

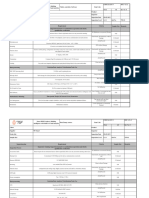

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Variables Perceived Bureaucratic Inuence Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness Term Limits Divided Government Executive Fragmentation State Employees per 10,000 citizens Chamber Size Member of Majority Party Member of Governors Party Democratic chamber Professionalization Chamber Ideology Nonwhite Legislator Democratic Legislator Citizen Ideology Perceived Legislative Staff Inuence

Observations 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705 2705

Mean 3.35 6.98 0.20 0.61 2.03 176.45 112.13 0.64 0.51 0.47 0.17 0.74 3.47 0.10 0.51 48.07 3.80

SD 1.24 1.58 0.40 0.49 1.26 52.88 85.02 0.48 0.50 0.50 0.11 0.44 1.49 0.30 0.50 15.44 1.47

Minimum 1 4 0 0 0 108 20 0 0 0 0.027 0 1 0 0 8.45 1

Maximum 7 10 1 1 4 451 400 1 1 1 0.626 1 7 1 1 95.97 7

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Independent Variable

To proxy bureaucratic effectiveness, we utilize the Maxwell Schools GPP overall management capacity grades for all states in 2001 (Barrett and Greene 2001). Although we would prefer to explore the impact of factual or actual effectiveness, creating measure across multiple agency types, service areas, and states is beyond scope of this study; thus, we rely on a validated measure of perceived effectiveness. The GPP score was designed to dissect the black box of government management in order to provide an inside look at how a government operates and how management is related to government performance. The GPP score is a measure of perceived capacity; it utilizes the judgments of state-level managers and opinion leaders on state performance in different management areas.6 The GPP assigned letter grades to the states for ve management subsystems: nancial management, capacity management, human resources management, information technology, and managing for results. Within each subsystem, criteria-based assessment was used to evaluate each state (Ingraham and Kneedler 2000), and based on a states grade for each subsystem, an overall management capacity grade was calculated. Because the states are given A through F grades, we have operationalized management capacity by assigning each state the corresponding number (i.e., F 5 0, D- 5 1, D 5 2, etc.). This variable ranges from 4 (C-) to 10 (A-).7

6 Given that we use survey instruments for the dependent variable (perceived bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes) and the key independent variable (perceived bureaucratic effectiveness), there is a potential concern that the ndings are generated by measuring the same concept on both sides of the equation. We do not think that this is a large concern because we are using different surveys to derive our dependent variable and key independent variable and the interactions provide plausible results. However, it is important to point out this potential complication in our analysis. 7 There are a number of factors that might predict the level of perceived effectiveness in a state, including bureaucratic analytic capacity. Thus, we do not this variable in the models in order to avoid an over-control. The factors leading to greater levels of perceived effectiveness is an interesting question for future research.

356

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

Before moving on, it is important to make the connection between perceived management capacity, our primary independent variable, and perceived bureaucratic effectiveness, our concept of interest. Management practices, like those measured by the GPP, have been empirically demonstrated to increase effective government performance in a variety of contexts. Evaluating county welfare-to-work programs, Sandfort (2000) shows a connection between a number of service technologies and delivery structures and the proportion of a countys caseload that is working. Similarly, student achievement is linked to initiatives aimed at ending social promotion in public schools (Roderick, Jacob, and Bryk 2000). The relationship between management characteristics and effectiveness is also found in Job Partnership Training Act programs (Heinrich and Lynn 2000; Jennings and Ewalt 1998), mental health networks (Milward and Provan 1998), and federal (Brewer 2005) and state agencies generally (Moynihan and Pandey 2005). Considering more general measures of managementcapacity,Donahue, Selden, and Ingraham (2000) nd that local governments human resources management capacity improves performance in human resources and Coggburn and Schneider (2003) link capacity to a measure of government performance (i.e., state policy priorities). As Donahue, Selden, and Ingraham (2000) note, there is a growing agreement that inuences associated with administrative arrangements do matter to the efcacy of the policy and program delivery system (384). In addition to the association between capacity and effectiveness discussed above, the GPP scores should serve as a powerful proxy for perceived effectiveness, which is ultimately what matters in the determination of power (Carpenter 2001). Bureaucracies with high management capacity scores can advertise these and the underlying elements that produced them. This should help them to be perceived as more effective by legislators, which we contend should allow them to wield more inuence over legislative policy formulation.

Interactions

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Given that there are a number of factors that could enhance the impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on the policymaking inuence of bureaucracies, we include a set of interactions drawn from both the literature on bureaucratic power in the implementation process and relevant work on legislative behavior. First, the information asymmetries that arise from bureaucratic expertise and foster bureaucratic inuence are relative and, in part, determined by the policy expertise of other institutional actors. In states, term limits have been shown to reduce policy expertise among legislators who typically have only 6 or 8 years in a given chamber to accumulate knowledge. Therefore, we include a measure indicating whether term limits were in effect in a state by 2002 and expect this measure to be positively associated with legislator perceptions of bureaucratic inuence in the policy process. In addition to this additive relationship, term limits may magnify the impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence on policy formulation by increasing the relative merit of the policy solutions offered by the bureaucracy, giving bureaucrats more sway in the negotiations surrounding legislative enactment. In order to test for this moderating effect, Model 2 includes a multiplicative interaction between our measure of effectiveness and the indicator of term limits, which we expect to be positive and signicant. Research also suggests that low levels of legislative professionalization decrease the expertise that lawmakers bring to the policy process, which we suggest may make them more likely to turn to competent bureaucratic sources. We capture legislative

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

357

professionalization with a measure that includes legislative salary, the number of days in session, and the number of legislative staff all relative to the US Congress. For details on this measure, see Squire (2007). Regarding the additive relationship, we expect professionalization to decrease the inuence of bureaucratic actors on legislative outcomes; professionalized legislators have large staffs, which may make them less likely to rely on the bureaucracy for input on legislation. To capture the potential conditional relationship between bureaucratic effectiveness and legislative professionalization, we interact these two variables; the results for this test are presented in Model 3. We expect this interaction to be negative and signicant, indicating that the impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on the inuence of the bureaucracy over legislative outcomes is greatest in the least professionalized chambers. Scholarship on the implementation process also suggests that the relative policy positions of political principals help to determine the discretionary decision-making power enjoyed by bureaucratic actors. We proxy the relative positions of institutional actors within a state with a measure of divided government. When different political parties control either the lower and upper chambers of the legislature or one chamber of the legislature and the governorship, the core within which bureaucrats have discretion to act should be larger. Thus, we expect this measure to be positively correlated with legislator perceptions of bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process. As noted above, we also expect that the relative preferences of political principals will moderate the impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic power in the legislative process because bureaucrats in divided government states work within a larger zone of discretion and may be able to foster relationships with a greater diversity of political principals. Model 4 includes a multiplicative interaction between bureaucratic effectiveness and the indicator of divided government, which we expect to be signicant and positively signed. Research on bureaucratic power suggests that leadership and cohesion have an impact on the inuence that bureaucracies have in the policymaking process. To capture the potential differences in the motivation of agency leaders and the cohesion of the administrative enterprise across states, we include a measure of executive fragmentation. Research suggests that fragmented executive arrangements within a state, where the heads of major agencies are elected rather than appointed, decreases the power of the executive branch by eliminating a shared sense of mission and set of goals among agencies (Beyle 1995). Another obvious consequence is a substitution of electoral for administrative values among agency heads who must answer to a constituency. In order to capture these differences and their potential impact on bureaucratic power, we include a 5-point measure of executive fragmentation. This measure is the reverse of Beyles separately elected state-level ofcials (SEP) measure and ranges from 0, indicating that only the governor or governor/lieutenant governor team are elected, to 4, indicating that the governor is elected with no team and that 7 or more process ofcials and several major policy ofcials are elected separately. We expect this measure to be negatively associated with legislator perceptions of bureaucratic inuence. Despite this negative main effect, we expect executive fragmentation to enhance the relationship between effectiveness and bureaucratic inuence in legislative policy development. We suggest that this should be the case because competency might be a more important source of inuence when the bureaucracy is seen as less of an extension of the governor. When bureaucratic agencies are viewed as more independent from the governor, the agencies will need to develop their own reputations for effectiveness and earn the

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

358

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

condence of legislators in their own right. Thus, bureaucratic effectiveness should be a more important source of bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes when the executive is unbundled. To capture our multiplicative expectation, we include an interaction between bureaucratic effectiveness and executive fragmentation in Model 5 and expect its coefcient to be positive and signicant.

Controls

The models include various controls capturing legislator characteristics and features of the legislative chamber and the state. First, we include controls for individual legislator traits, which may inuence their perceptions of bureaucratic power in the legislative process. The rst of these is political party, coded 1 for Democrat and zero otherwise, and separate indicators of whether the legislator is the same party as the governor and in the majority party in the chamber. We expect all these to correlate negatively with perceptions of bureaucratic inuence. We also include controls for ideology, measured on the standard 7-point scale with higher values corresponding to greater liberalism. Analogous to party, we expect this measure to correlate negatively with perceived bureaucratic power in the legislative process. As a nal individual control, we include legislator race, coded 1 for nonwhite legislators. We do not have an expectation regarding the impact of this variable on perceptions. Data on party, ideology, and race are self-reported by legislators. Models also control for characteristics of the legislative chamber and the state. We include measures of chamber type (1 5 lower chamber), relevant chamber size, which is gathered from the Book of the States, the majority party of the chamber, coded 1 for Democratic control and zero otherwise, citizen ideology (Berry et al. 1998), and the number of state employees per 10,000 state citizens. Although we do not have expectations regarding the rst four control variables, we expect the number of state employees to have a positive correlation with perceptions of bureaucratic inuence. The number of state employees is a proxy for the resources that a state dedicates to the administration of policy, which may be an important source of bureaucratic inuence (Clarke and McCool 1996; Meier 2000). Finally, all models contain a control for the differential use of Likert scales by different legislators responding to questions regarding institutional power. Some persons tend to mark higher values on these scales, regardless of the subject, whereas others systematically favor lower values. One way to address this bias is to normalize the response on the variable of interest relative to some obvious reference category. For our model, we control for the differential use of Likert scales by including the respondents perceptions regarding the power of another group involved in policymaking in their statelegislative staff. The ndings reported below are unchanged if this control is left out of the model, but the positive and signicant coefcient suggests that it should be included.

Methods

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

The models discussed below are estimated as weighted ordinary least squares regressions. As noted above, the weighting parameter ensures that legislators from all states, regions, genders, chambers, etc., have proportional inuence on observed relationships. The dependent variable is a 7-point scale, which is a sufcient number of categories for Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) to produce very similar results to an ordered logistic regression

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

359

(Jaccard and Wan 1996). As a robustness check, we estimate the models as ordered logits and the ndings remain unchanged.8 We also ran a simultaneous equations model to consider the potential for simultaneous causation between perceived bureaucratic effectiveness and perceived bureaucratic inuence, and conducted a matching analysis. The results of these analyses are available at the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory online. Thus, we report OLS models because it makes the interpretation of results more intuitive. The models report standard errors that are clustered by state.

FINDINGS

The models considering the impact of perceived effectiveness and perceived bureaucratic inuence are presented in Table 2. The results are presented in ve separate models. For each model, we review the ndings for the key independent variable, bureaucratic effectiveness, and any interaction. Because the results for the control variables are stable across the models, we discuss the control variables at the end of this section. Model 1 presents the results for the additive model, considering the direct effect of perceived bureaucratic effectiveness, as measured by the GPP management capacity score, on legislators perceptions of bureaucratic inuence over policy outcomes. As expected, bureaucratic effectiveness positively inuences perceived bureaucratic power. Substantively, shifting the effectiveness measure from its minimum (4) to its maximum value (10), or moving from Alabama to Michigan, increases bureaucratic inuence by 0.26 on the perceived inuence scale, which about the same effect on perceived bureaucratic inuence as moving from a term-limited to a nonterm-limited state. This nding suggests that bureaucracies with greater perceived effectiveness enjoy enhanced perceived inuence over legislative outcomes and corroborates previous scholars notions about the relationship between effectiveness and inuence. In Model 2, we examine whether term limits enhance the positive impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence by considering the interaction between perceived bureaucratic effectiveness and term limits. As expected, the interaction is positive and signicant, indicating that in states that have implemented legislative term limits, effectiveness has a larger impact on the perceived inuence of bureaucrats over legislative outcomes. Substantively, in states with term limits, holding all else constant, as bureaucratic effectiveness moves from is minimum value (4) to its maximum value (10), bureaucratic policymaking inuence increases by 0.71, which is almost a 10% increase in the total range of the perceived inuence scale. As indicated by the coefcient for the bureaucratic effectiveness component, in states without term limits, bureaucratic effectiveness still has a positive effect on bureaucratic inuence, just of a lesser magnitude. Holding all else constant, as bureaucratic effectiveness moves from is minimum value to its maximum value, bureaucratic policymaking inuence increases by 0.20 in nonterm-limited states.8 The impact of bureaucratic effectiveness is close to four times greater in states that have term limits than in those that do not. Taken together, the results suggest that effectiveness is an important source of bureaucratic inuence for over policy formulation regardless of term limits; however, the effect is much greater in states that have implemented this legislative reform.

8 The coefcient for term limits is negatively signed, which is somewhat counter intuitive. It is important to remember, however, that this represents the impact of this reform in states where bureaucratic effectiveness is 0, which never occurs in our data.

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Table 2 Determinants of Perceived Bureaucratic Inuence

Model 1 Coefcient (robust SE)

Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness Term Limits Term Limits 3 Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness Professionalization Professionalization 3 Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness Divided Government Divided Government 3 Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness Executive Fragmentation Executive Fragmentation 3 Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness State Employees Chamber Size Member of Majority Party Member of Governors Party Democratic Chamber Chamber Legislator Ideology Nonwhite Legislator Democratic Legislator 0.0439** (0.0175) 0.322*** (0.0856)

Model 2 Coefcient (robust SE)

0.0326* (0.0170) 20.249 (0.202) 0.0862*** (0.0296)

Model 3 Coefcient (robust SE)

0.0192 (0.0415) 0.318*** (0.0873)

Model 4 Coefcient (robust SE)

0.0589** (0.0249) 0.321*** (0.0864)

Model 5 Coefcient (robust SE)

20.0194 (0.0419) 0.305*** (0.0880)

21.504*** (0.333)

21.550*** (0.313)

22.426* (1.375) 0.142 (0.224)

21.524*** (0.333)

21.548*** (0.335)

20.114 (0.0732)

20.0933 (0.0726)

20.103 (0.0810)

0.0694 (0.275) 20.0255 (0.0390)

20.155* (0.0796)

20.0422 (0.0312)

20.0357 (0.0302)

20.0417 (0.0309)

20.0372 (0.0334)

20.232** (0.0982) 0.0265* (0.0142)

0.000555 (0.000634) 0.000140 (0.000472) 20.263*** (0.0454) 0.107** (0.0472) 0.151* (0.0775) 0.111 (0.0816) 0.0490** (0.0213) 0.198** (0.0932) 20.0331 (0.0669)

0.000585 (0.000627) 0.000613 (0.000637) 0.000602 (0.000651) 8.65 10205 (0.000725) 205 205 0.000101 (0.000454) 4.08 10 (0.000530) 9.75 10 (0.000465) 20.000304 (0.000511) 20.261*** (0.0460) 20.262*** (0.0462) 20.264*** (0.0454) 20.265*** (0.0457) 0.110** (0.0475) 0.107** (0.0477) 0.109** (0.0465) 0.105** (0.0477) 0.157** (0.0764) 0.105 (0.0802) 0.0491** (0.0210) 0.193** (0.0927) 20.0303 (0.0668) 0.156** (0.0760) 0.115 (0.0817) 0.0499** (0.0214) 0.196** (0.0930) 20.0350 (0.0674) 0.152* (0.0777) 0.113 (0.0813) 0.0494** (0.0214) 0.198** (0.0933) 20.0341 (0.0674) 0.160** (0.0786) 0.144* (0.0852) 0.0477** (0.0213) 0.184* (0.0951) 20.0271 (0.0665)

Continued

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Table 2 (continued) Determinants of Perceived Bureaucratic Inuence

Model 1 Coefcient (robust SE)

Citizen Ideology Perception of Legislative Staff Constant Observations R2 29.77 1025 (0.00214) 0.244*** (0.0184) 2.141*** (0.262) 2705 0.121

Model 2 Coefcient (robust SE)

20.000281 (0.00215) 0.244*** (0.0185) 2.207*** (0.250) 2705 0.122

Model 3 Coefcient (robust SE)

20.000140 (0.00214) 0.244*** (0.0185) 2.284*** (0.324) 2705 0.121

Model 4 Coefcient (robust SE)

29.64 1025 (0.00220) 0.244*** (0.0183) 2.018*** (0.316) 2705 0.121

Model 5 Coefcient (robust SE)

20.000246 (0.00236) 0.244*** (0.0181) 2.742*** (0.473) 2705 0.122

***p , .01, **p , .05, *p , .10, two-tailed test. Note: Bold entries indicate our key independent variables.

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

362

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

Model 3 considers the potential interaction between legislative professionalization and bureaucratic effectiveness. The coefcient for professionalization is negative and signicant, indicating that legislators in more professionalized chambers are less likely to perceive high levels of bureaucratic inuence in the policy process when bureaucratic effectiveness equals 0 (an effectiveness value that does not exist in our data). Contrary to our expectations, the interaction term is not statistically signicant, suggesting that the level of professionalization does not moderate the impact of effectiveness on perceived bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process. We offer some discussion of the potential explanations for this nding, along with an acknowledgement of the need for further research, in the conclusion. The impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on perceived inuence as moderated by divided government is considered in Model 4. In this model, we do not nd the expected relationship. Effectiveness does not have a greater impact on bureaucratic inuence over policy formulation in states with divided government. It is actually states with united governments where effectiveness enhances bureaucratic inuence. In united government states, holding all other variables constant, perceived bureaucratic inuence increases by 0.35 as effectiveness shifts from its minimum to its maximum value. This suggests that in states where there is no party competition between the branches or chambers, effective bureaucracies enjoy greater policymaking inuence than ineffective bureaucracies. However, when the branches and chambers are engaged in partisan battles, effectiveness is not a source of bureaucratic inuence. This contrary result may suggest that when the government is divided, particularly between the executive and legislative branches, bureaucratic actors become less inuential in the policymaking process, regardless of competency.9 Despite the fact that the bureaucracy has more room to maneuver in the implementation process when the branches and chambers are divided by partisanship, a partisan lter may devalue bureaucratic expertise and limit the bureaucracys inuence in legislative policy discussions. The negative and signicant effect of divided government in Model 5 is suggestive of this explanation. Model 5 presents the results for the interaction between perceived bureaucratic effectiveness and executive fragmentation. The results suggest that when the executive branch is consolidated (i.e., fragmentation 5 0), effectiveness does not play a signicant role in determining bureaucratic inuence, as indicated by the null coefcient for the bureaucratic effectiveness variable.10 However, as the executive branch becomes more fragmented, effectiveness becomes an important source of bureaucratic inuence over policy formulation, which is evidenced by the signicant coefcient for the interaction. This relationship is consistent with our expectations and suggests that when bureaucracies are not viewed as extensions of the governors ofce and agency ofcials have to cultivate their own reputations, effectiveness becomes increasingly important for determining bureaucratic inuence over policy formulation.

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

9 When including a measure of divided government only between the executive and legislative branches (i.e., only divided if the governor is from one party and the two chamber majorities are from another party) and the interaction with bureaucratic effectiveness, the results are consistent with those presented. 10 The coefcient for fragmentation is negatively signed, which indicates that when bureaucratic effectiveness equals 0, executive fragmentation diminishes perceived bureaucratic inuence. It is important to remember that bureaucratic effectiveness never equals 0 in our data.

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

363

Figure 1 Impact of Perceived Bureaucratic Effectiveness by Executive Fragmentation with 95% Condence Interval

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

This relationship is further explored in gure 1. As illustrated by the graph, it is only when fragmentation approaches 2.5, which means that the governor is elected alone (i.e., without a lieutenant governor team) and six or fewer other ofcials are also elected separately, that effectiveness starts to have a signicant impact on perceived bureaucratic inuence, and this positive effect continues as fragmentation deepens. The marginal effect of perceived bureaucratic effectiveness increases from 20.02 (but indistinguishable from 0) to 0.09, as fragmentation moves from its minimum level (0) to its maximum (4). When executive fragmentation is at its highest level and bureaucratic effectiveness is shifted from its minimum value to its maximum value (with the interaction held at the corresponding value and all other variables held constant), perceived bureaucratic inuence increases by 0.52. This nding suggests that when the executive branch is a united team, effectiveness does not contribute to the legislative policymaking inuence of the bureaucracy, perhaps because other factors, such as partisanship, are more important. However, as the executive branch becomes increasingly fragmented and bureaucracies are viewed as more independent from the governor, it becomes increasingly important for agency ofcials to develop their own relationship with legislators. Under these circumstances, more capable bureaucracies attain greater legislative policymaking inuence. These ndings have important implications for policymakers and bureaucrats. Agency ofcials (and other government stakeholders) should be aware of the potential power of bureaucratic competency and also understand the circumstances that enhance the relationship between effectiveness and bureaucratic inuence over legislative policy formulation. Given the direct relationship between perceived bureaucratic effectiveness and perceived

364

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

Table 3 Table 3 Impact of Perceived Effectiveness (Minimum to Maximum Change)

Estimated Level of Inuence (Effectiveness 5 4) Term limits No term limits United government Fragmentation (highest level) 3.13 3.03 3.06 2.76

Estimated Level of Inuence (Effectiveness 5 10) 3.84 3.23 3.41 3.28

Difference 0.71 0.20 0.35 0.52

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

inuence over legislative outcomes, if agency ofcials seek legislative inuence, then they should be conscious of their agencys reputation for competency and expertise. Managers can work not only to improve their agencys effectiveness in the implementation of policy but also to advertise their accomplishments because reputations for excellence function as currency, purchasing inuence in the legislative process. The relationship between perceived effectiveness and perceived inuence over legislative outcomes is enhanced by three state characteristics. Expert bureaucrats have greater inuence in states with term limits, a united government, and high levels of executive fragmentation. table 3 provides point estimates for the level of bureaucratic inuence and summarizes the impact of effectiveness as it shifts from its minimum to maximum value under each of these conditions. Term limits amplify the impact of effectiveness to the greatest extent, with fragmentation and united government being associated with a more modest change in the impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes. The larger impact under term limits makes sense given that term limit completely alter the experience level of legislators, leaving a void of expertise, whereas the other two factors have a less pronounced potential connection to inuence over legislative outcomes. As a nal method for putting the results discussed above in context, we compare our empirical predictions to the actual responses from legislators in states with different mixes of characteristics. This allows us to visualize the impact of more permutations of effectiveness and institutional characteristics on perceived inuence than does an examination of predicted values because we estimate interactions of these variables in separate equations. It is also a nice check of the accuracy of our theoretical and empirical story. Our models suggest that bureaucracies should have greater perceived inuence in states with high levels of bureaucratic effectiveness (!7), term limits, unied government, and fragmented executives (!2) and that is exactly what we nd. The mean level of perceived inuence in states with these characteristics (e.g., Michigan and Florida) is 3.61. Compared to states that t all four of the criteria, the models also suggest that perceived inuence should be diminished if all these conditions are met except the state does not have term limits; the average perceived inuence score of 3.48 in these states (e.g., North Carolina and Kansas) conrms this expectation. As a nal example, the models suggest that perceived inuence should be at its lowest levels in states with ineffective bureaucracies ( 6), no term-limits, divided government, and consolidated executives ( 1). On average, legislators in the states where these conditions hold (e.g., Alaska and New Hampshire) place perceived

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

365

bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes at 3.2, which again highlights the importance of these factors for bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process.11 Before moving on to the conclusions, it is important to discuss the effect of the control variables on bureaucratic inuence. Term limits consistently increase the perceived inuence of bureaucrats, which is in line with the arguments that term limits diminish the power of the legislature relative to other institutional actors (Carey et al. 2006). As mentioned above, in Model 5, divided government reduces the perceived inuence of bureaucrats, suggesting that when the branches and chambers are engaged in partisan conict, bureaucracies have less inuence over policymaking, presumably because of their role in the executive branch. Liberal legislators, members of the governors party, and legislators serving in Democratic chambers perceive bureaucrats as more inuential. In addition, nonwhite legislators view bureaucrats as possessing greater inuence than their white counterparts, and the perceived power of legislative staff positively affects perceived bureaucratic inuence. Alternatively, professionalization decreases perceived bureaucratic inuence, indicating that more professionalized chambers view bureaucrats as less important to legislative outcomes. Also, members of the majority party hold bureaucratic inuence as less meaningful than their minority colleagues.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

In this article, we explore the relationship between perceived bureaucratic effectiveness and the perceived inuence of this institution in legislative policy formulation. We also consider factors that may moderate the impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence. When looking across the US states, we nd that greater effectiveness enables bureaucracies to exact a more meaningful inuence on outcomes in the legislative arena. This supports Carpenters (2001) claim regarding the link between effectiveness and bureaucratic autonomy in the policymaking process and the argument that competency is an important antecedent to bureaucratic power. Importantly, this nding also indicates that the effect holds (1) for assessments of the bureaucracy as a whole (rather than just for singular agencies) and (2) across 50 distinct governments. The ndings are also signicant because they suggest that the link between bureaucratic effectiveness and inuence over legislative policy formulation is moderated by institutional features of a government. We nd that term limits enhance the positive impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process. This indicates that when legislators do not have time to develop their own expertise on policy matters, they are increasingly reliant on competent bureaucratic actors for their knowledge, giving bureaucrats with a reputation for effectiveness an even greater role in formulating policy. In other words, the results suggest that, in term-limited states, effective bureaucracies are becoming even more essential to the policy process. This also signals that states with naturally high

11

As additional examples, we would expect values of perceived bureaucratic inuence somewhere in the middle of those mentioned here when (1) the government is united but legislators are not term limited and the executive branch is relatively consolidated or when (2) the executive is fragmented but legislators are not term limited and the government is divided, even if the bureaucracy is effective. Again, the actual responses of legislators bear out these expectations, with a mean level of perceived inuence of 3.32 for states tting the former description (e.g., Maryland and Utah) and 3.28 for states meeting the latter criteria (e.g., Delaware and Texas).

366

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

legislative turnover not induced by term limits may afford effective bureaucracies a more prominent policymaking role, which is an area for additional research. Additionally, united governments, as opposed to divided governments, augment the positive impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence over legislative outcomes. This indicates that when legislators and the executive are not divided by partisanship, effectiveness is linked to bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process, and when there is partisan division between the branches, effectiveness is an insignicant predictor of this inuence. Given the high levels of political polarization in the contemporary period, it would be interesting to investigate this relationship over time to see if it would manifest during a less polarized era. We also nd that perceived effectiveness is a more important determinant of bureaucratic inuence in policy development when the executive is highly fragmented. This is an intriguing nding and suggests that as the ties between bureaucrats and the executive are increasingly severed and bureaucratic agents are forced to develop their own reputations, quality performance is an important source of bureaucratic inuence in the policy process. This furthers our understanding of the relationship between effectiveness and bureaucratic inuence in that effectiveness becomes a more critical component of bureaucratic inuence when bureaucrats are increasingly removed from the executive. This points to future research considering whether effectiveness is more valuable in terms of gaining inuence in the legislative process for bureaucratic agencies that are more politically independent from the executive, such as independent regulatory commissions at the federal level. Contrary to our expectation, we do not nd evidence that bureaucratic effectiveness has a larger impact on bureaucratic inuence in less professionalized chambers. We suggested that this might be the case because these legislators are less able to gather their own policy expertise, and may, therefore, be more likely to turn to an effective bureaucracy for that expertise. There are a couple of logical explanations, however, that might address why we do not observe this relationship. First, the null interactive effect may indicate that nonprofessionalized legislators use bureaucratic advice, regardless of bureaucratic effectiveness, because they need any and all counsel that they can get, given their low levels of legislative staff. Another potential explanation may lie in the complex relationship discovered by scholars between legislative professionalization or staff resources and the design of bureaucratic agencies in the states (see Huber, Shipan, and Pfaler 2001; Reenock and Poggionne 2004). The impact of this potential relationship on the inuence of bureaucratic actors in the legislative process and other potential links between legislative professionalization and the utilization of bureaucratic expertise must be explored further in future research. As noted in the Introduction, we are interested in better understanding the impact of bureaucratic effectiveness on the inuence enjoyed by that institution in the legislative process for a variety of reasons. Most notable among these is the recognition that there has been relatively little empirical research on the topic. With this article, we contribute to this area by considering the relationship between bureaucratic effectiveness and inuence over legislative policy formulation across the US states and outlining conditions that enhance this relationship. Our ndings add to our knowledge of how bureaucratic agents achieve inuence in the policy process and when effectiveness is an important contributor. The results are also interesting from larger governmental reform perspective. The institutional features of government that condition bureaucratic inuence are not static. Obviously, divided government is the least stable characteristic and can change every

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

367

2 years in most states. The level of executive fragmentation in a state is also occasionally revised, with seven states altering the extent to which their executive branch was bundled between 2002 and 2007.12 Although Nebraska was the last state to adopt term limits in 2000, term limits could easily be enacted in more states (most likely in those that allow citizen initiatives). Even more likely is the possibility that limits will be repealed in the states that currently utilize them; Wyoming was the most recent state to do so in 2004. If governmental actors are interested in (or concerned about) increased bureaucratic inuence in the legislative process, then they must be cognizant that such inuence may be an externality of these types of institutional reforms. Additionally, the questions addressed in this article merit attention because of the recent focus on accountability and performance in the public sector. Many recent reforms of bureaucratic and management systems at both the federal and state levels have targeted performance and explicitly sought to increase bureaucratic effectiveness (Bourdeaux and Chikoto 2008; Ingraham and Kneedler 2000), and there is some evidence of their success (Governmental Accounting Standards Board 2000; Liner et al. 2001). Our ndings suggest that state-level reforms that have been successful in increasing bureaucratic effectiveness have also amplied the power of bureaucracies in the legislative process. As such, management reforms directed at improving bureaucratic performance can be viewed as sources of bureaucratic inuence, and those who wish to build the inuence of bureaucrats in the policymaking process would do well to implement them (and vice versa). Taking these ndings into account, myriad questions regarding bureaucratic inuence over policy formulation still remain, and we echo previous calls for more research on the subject. Several questions are suggested by this research, such as further consideration of factors that enhance the impact of effectiveness on bureaucratic inuence. Moreover, there is a great deal of room for research not only exploring how bureaucrats gain power and under what conditions but also considering the consequences of extensive bureaucratic participation in the policy formulation process. This is an important topic, one that is vital for a comprehensive understanding of the role of the bureaucracy in our democratic system, and there are many questions left to address.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Supplementary material is available at the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory online.

REFERENCES

Austen-Smith, David. 1997. Interest groups: Money, information, and inuence. In Perspectives on public choice, ed. Dennis C. Mueller. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press. Bachrach, Peter, and Morton S. Baratz. 1962. Two faces of power. The American Political Science Review 56:94752. Barrett, Katherine, Richard Greene and Michele Mariani. February 2001. Grading the states: A management report card. Governing.

12

This calculation is based on the number of states that changed scores on Beyles scale of separately elected executive branch ofcials between 2002 and 2007. These data are available at http://www.unc.edu/~beyle/ gubnewpwr.html.

368

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

Berman, David. 2004. Effects of legislative term limits in Arizona. Final Report for the Joint Project on Term Limits. http://www.ncsl.org/jptl/casestudies/CaseContents.htm (accessed August 2, 2011). Berry, Christopher R., and Jacob E. Gersen. 2008. The unbundled executive. The University of Chicago Law Review 75:1385434. Berry, William D., Evan J. Ringquist, Richard C. Fording, and Russell L. Hanson. 1998. Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American states, 196093. American Journal of Political Science 42:32748. Beyle, T. 1995. Enhancing executive leadership in the states. State and Local Government Review 27:1835. Beyle, Thad, and Margaret Ferguson. 2008. Governors and the executive branch. In Politics in the American states: A comparative analysis, 9th ed., ed. Virginia Gray and R. L. Hanson, 192228. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Bourdeaux, Carolyn, and Grace Chikoto. 2008. Legislative inuences on performance management reform. Public Administration Review 68:25365. Bowman, Ann, and Richard C. Kearney. 1986. The Resurgence of the States. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Brewer, Gene. 2005. In the eye of the storm: Frontline supervisors and federal agency performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15:50527. Cain, Bruce E., and Thad Kousser. 2004. Adapting to term limits: Recent experiences and new directions. Final Report for the Joint Project on Term Limits. http://www.ncsl.org/jptl/casestudies/Case Contents.htm. (accessed August 2, 2011). Carey, John M., Richard G. Niemi, Lynda W. Powell, and Gary Moncrief. 2002. 2002 State Legislative Survey. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. ICPSR 20960. Carey, John M., Richard G. Niemi, Lynda W. Powell, and Gary F. Moncrief. 2006. The effects of term limits on state legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly 31:10534. Carpenter, Daniel. 2001. The forging of bureaucratic autonomy: Reputations, networks, and policy innovation in executive agencies 18621928. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. . 2010. Reputation and power: Organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Carroll, James D. 1995. The rhetoric of reform and political reality in the national performance review. Public Administration Review 55:30212. Christensen, Robert, Holly Goerdel, and Sean Nicholson-Crotty. 2011. Management, law, and the pursuit of the public good in administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (Suppl 1): 12540. Clarke, Jeanne Nienaber, and Daniel McCool. 1996. Staking out the terrain: Power and performance among natural resource agencies. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. Coggburn, Jerrell D., and Saundra K. Schneider. 2003. The quality of management and government performance: An empirical analysis of the American states. Public Administration Review 63:20613. Dahl, Robert A. 1957. The concept of power. Behavioral Science 2:20115. . 1961. Who governs?: Democracy and power in an American city. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press. Dahl, R. A., and C. E. Lindblom. 1953. Politics, economics and welfare. New York: Harper and Brothers. Donahue, Amy K., Sally C. Selden, and Patricia W. Ingraham. 2000. Measuring government management capacity: A comparative analysis of city human resource management systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10:381411. Durant, Robert F. 1991. Whither bureaucratic inuence?: A cautionary note. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 1:46176. Freeman, J. Leiper. 1958. The bureaucracy in pressure politics. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 319:109. Friedrich, Carl J. 1941. Constitutional government and democracy. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Downloaded from http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/ at Hunter College Library on September 4, 2012

Nicholson-Crotty and Miller Bureaucratic Effectiveness and Inuence in the Legislature

369