Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Human Intelligence Sources - Challenges in Policy Development

Uploaded by

shakes21778Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Human Intelligence Sources - Challenges in Policy Development

Uploaded by

shakes21778Copyright:

Available Formats

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

Charl Crous

Police organisations are developing Intelligence Led Policing initiatives to enhance the knowledge of the criminal environment for effective resource deployment. One of the key policing techniques available to police is the use of Covert Human Sources formerly also known as criminal informers. The policeinformer relationship has been known as a high risk relationship especially in the area of ethics and integrity. A number of commissions of inquiry has also criticised this relationship. This paper reflects on the challenges for police to develop policy to ensure a professional framework for policehuman source conduct. The paper reflects on what an effective human source is in the criminal intelligence sense and what the basic elements of an effective operational framework are. Thus what enables the wise sovereign and the good general to strike and conquer, and achieve things beyond the reach of ordinary men, is foreknowledge. Now this foreknowledge cannot be elicited from spirits, it cannot be obtained inductively from experience. Knowledge of the enemies dispositions can only be obtained from other men. Sun Tzu, On The Art Of War, (Toronto: Global Language Press, 2007).

Understanding the criminal environment is the cornerstone of reducing crime and minimising victimisation. The aim of this paper is to discuss the need for police to develop and implement a professional, effective and ethical Human Source Management (HSM) framework to enhance police knowledge of the criminal environment from area level command to international policing, but also to emphasise the challenges involved in doing so. Human intelligence sources should be an integral part of police intelligence doctrine and practices. The paper broadly defines the role of human sources in contemporary policing, specifically in terms of intelligence gathering. The ethical management of sources is of paramount importance, and integrating HSM practices with the formal police intelligence framework is a challenge as the use of sources has traditionally been reserved as a detective function to be deployed when specific crimes are investigated. Police face a challenge to develop policy that will see the modernisation of this covert policing practice as the policeinformer relationship has been criticised in the past for being a relationship that lends itself to corruption and unethical behaviour. The challenge to develop policy in this regard is against a background of the need for police to expand the knowledge base

Security Challenges, vol. 5, no. 3 (Spring 2009), pp. 117-127.

- 117 -

Charl Crous

of the criminal environment as well as the emphasis on police to ensure 1 intelligence-driven, risk-based policing practices.

Defining Human Sources in Contemporary Policing

The community provides information to police in many forms. Greer 2 distinguishes between informants and informers. According to Greers definition, informants are people who provide police with information about any matter however useful this information is. In contrast, the police informer is a person who has a particular motivation to provide specific information to police, who normally associates with those in the criminal world and who expects police to maintain a level of secrecy in terms of his or her relationship with police. Over the last decade, intelligence development in policing has expanded to such an extent that the term police informer is outdated as police intelligence practices include modernising and professionalising the traditional policeinformer relationship. As part of modernising the police officerinformer relationship, the term informer has been replaced by such terms as Covert Human Intelligence Source (CHIS), Human Source (HS) or human intelligence source. There is no general single definition in police or law enforcement for human intelligence sources as policing agencies in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and the United States define sources differently. However, the various definitions have some commonality. An HS can be described as a person with specific or general knowledge about criminality and the criminal market, who has a long-term relationship with the police, who can be deployed by the police and who might seek to receive some form of reward. Sources are thus any persons who consciously and, in a covert manner, provide information to police, whether there is expectation of reward or not, 3 but with an understanding that police will protect their identity.

C. Dunningham and C. Norris, Some Ethical Dilemmas in the Handling of Police Informers, Public Money & Management (JanuaryMarch 1998), pp. 215; P. Cooper and J. Murphy, Ethical Approaches for Police Officers when Working with Informants in the Development of Criminal Intelligence in the United Kingdom, Journal of Social Policy, vol. 26, no. 1 (1997), pp. 120; R. Billingley,The Police Informer / Handler Relationship: Is it Really Unique?, International Journal of Police Science and Management, vol. 5, no. 1 (2003), pp. 50-62. R. Billinsgley, Process Deviance and the Use of Informers: The Solution', Public Research and Management, vol. 6, no. 2 (2004), pp. 6787. 2 S. Greer, Towards a Sociological Model of the Police Informant, British Journal of Sociology, vol. 46, no. 3 (1995), pp. 50927. 3 Surrey Police, Managing Informants and Contacts: Force Policy Document, (Surrey Police, 1997); New Zealand Customs Services, 'Policy on the New Zealand Customs Service Registered Informant Programme', (Wellington: New Zealand Customs Services, 2005); New Zealand Police, Informer Policy and Guidelines, (Wellington: New Zealand Police, 1996); Victoria Police, Chief Commissioner's Instruction: Informer Management Policy, (Melbourne: Victoria Police, 2004); Tasmania Police, Informant Management Policy Document (Tasmania: Tasmania Police, 1999); Queensland Police, 'Draft Policy and Procedures State Informant Management System (SIMS), (October 2000); New South Wales Police, NSW Police Informant Management (Sydney: NSW Informant Management and Intelligence Centre, 2004); South

- 118 -

Security Challenges

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

Effective HS is the product of the following three factors: Access to criminal information; Motivation to bring crime-related information to police attention; and Control of police who will direct his or her activity.

4

The Need to Develop Human Source Capability in Policing

Police are responsible for reducing crime and ensuring community safety. Contemporary policing emphasises the need for police organisations to have extensive knowledge of the criminal environment and to deploy resources in a prioritised manner. The need to engage with the community is thus now more important than ever. One effective way of doing this is to re-evaluate the way police deal with those in the community who have access to the criminal environment but who are at the same time willing to work with police. Arguably, one of the most significant enablers for HSM in modern policing came with the publication of the 1993 Audit Commission report, 5 Helping with Inquiries, Tackling Crime Effectively. The report stated that criminal informants were the lifeblood of police and advocated an emphasis on their use in the United Kingdom with the aim of reducing crime. Police can harness the knowledge and skills of those people in the community with access to the criminal world (potential sources) by implementing a structured, well-resourced HSM framework. The development of professional HSM practices is an essential tool for crime reduction and should be an integral part of the intelligence-led policing philosophy. Despite impressive advances in the intelligence management field in terms of technical data analysis and collection, the use of human intelligence sources has not always provided accurate and quality intelligence. The 9/11 Commission of Inquiry, for example, severely

Australia Police, Human Source Management: General Order (Adelaide: State Intelligence Branch, September 2005); An Garda Siochana, Code of Practice for Garda Personnel Involved in the Management and Use of Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Ireland: An Garda Siochana, 2004); Los Angeles Police Department, Informant Manual (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Police Department, 2003). 4 P. Hanvey, Identifying, Recruitment and Handling of Informants (The Home Office, Police Research Group, 1995); J. Madinger, Confidential Informant: Law Enforcements Most Valuable Tool (CRC Press LLC, 2000). 5 Audit Commission, Helping with Enquiries: Tackling Crime Effectively (London: Audit Commission, 1993).

Volume 5, Number 3 (Spring 2009)

- 119 -

Charl Crous

criticised the US Central Intelligence Agency in the aftermath of the 11 6 September 2001 bombings for a lack of HS capability. Since the start of the new millennium it became evident that police have to develop new ways of engaging with the community to reduce crime and victimisation and to secure community safety. The need for police to develop HS networks in communities, and specifically in those at-risk communities, is becoming an essential element in crime reduction and domestic security initiatives. The fragile nature of community safety was exposed by various domestic security incidents across the world during the last eight years: the 9/11 attacks in the United States, the Madrid bombings, the Bali bombings and the London bombings in 2005. Although the use of sources has developed as a major crime control technique, especially in the organised crime arena during the last thirty years in Australasia, the United Kingdom and the United States, it could be argued that police organisations 7 have not done enough to expand the practice to other areas of policing. Although the policeinformer relationship has been severely criticised, many police and law enforcement organisations have recently moved from a traditional policeinformer relationship to a more comprehensive, professional and ethical system of recruiting and managing sources. The introduction of dedicated source-handling units and HSM units in various police jurisdictions in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand is contributing significantly to the development of professionalism in intelligence gathering covering a vast area of criminality, including domestic security. The advantages of specialised HSM units are many. They provide professional management of sources and a high level of oversight in terms of the wider policeHS relationship. HSM units are also subjected to formal independent audits with a range of accountability systems in place, ensuring 8 quality standards while minimising most risks associated with HSM. For police, employing HS services remains a high-risk tactic. Police corruption, ethical source management and poor intelligence management are high-risk areas that need to be managed with adequate policy design. Nevertheless, with this warning comes the acknowledgement that the potential positive outcomes in terms of crime reduction and safer

A. Dupont, Intelligence for the Twenty-First Century, Intelligence and National Security, vol. 18, no. 4 (Winter 2002), pp. 1539. USA National Archives and Resource Center, National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the USA, The 9/11 Commission Report (2004). 7 M. Innes, Professionalizing the Role of the Police Informant: The British Experience, Policing and Society, vol. 9 (2000), pp. 35783; R. Rosenfield, B. A. Jacobs and R. Wright, Snitching and the Code of the Street, British Journal of Criminology, vol. 43 (2003), pp. 291309. 8 Innes, Professionalizing the Role of the Police Informant: The British Experience; Greer, Towards a sociological model of the police informant; M. Maguire and T. John, Intelligence, Surveillance and Informants: Integrated Approaches (London: Police Research Group, The Home Office, HMSO, 1995).

6

- 120 -

Security Challenges

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

communities by using sources in an ethical, professional and well-structured intelligence model, outweighs the risks associated with the practice. The relationship between police and sources remains controversial, 9 however, especially when participant informers receive a license to commit 10 crime by the nature of their relationship with police. Various commissions of inquiry in Australia, the United Kingdom and United States have identified the risks associated with using HS and a significant number of recommendations and guidelines have been published in different countries 11 because of this. The management of professional and ethical HS practices is about supporting the intelligence function within police services while still remaining a key investigative tool for police. Modern police intelligence practices require HS practices to be fully integrated into the intelligence management framework of the organisation. HS intelligence practices need to support and inform the development, production and dissemination of key intelligence products that support the knowledge base of police in the form of strategic assessments, tactical assessments, target profiles and problem profiles. Crime intelligence and analysis can be greatly enhanced by the addition of reliable, timely and effectively managed HS information. Developing an HSM framework from area to national level fits well with proactive community policing. The challenge is to ensure coordinated, integrated and ethical HS practice. In contrast to the traditional approach of informants being used for crime investigation per se, contemporary policing reforms require the use of sources to support proactive policing strategies which aim to understand criminality better and keep communities safe. A professional and ethical HSM framework consists of robust integrity measures and ensures alignment between various policing jurisdictions. It also allows a focused, centralised and ongoing intelligence capacity in the organisation to inform strategy development, decision making, resource allocation and guide interventions aimed at reducing crime and domestic security risks.

The participant informant is one who is allowed to carry on with committing a crime in order for police to determine who involved in organising the criminal action. 10 Billingsley, 'Process Deviance and the Use of Informers: The Solution'; Billingley, 'The Police Informer / Handler Relationship: Is it Really Unique? J. R. T. Wood, Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service, Final report, vol. 2 (Sydney: Government of the State of NSW, 1997); G. Fitzgerald, Report of the Commission of Inquiry Pursuant to Orders in Council (Brisbane: Queensland State Government, 1989); G. A. Kennedy, Royal Commission into whether there has been Corrupt or Criminal Conduct by any Western Australian Police Officer, Final Report (Perth: Government of the State of Western Australia, 2004); M. Mollen, Commission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption and the Anti-Corruption Procedures of the Police Department: Commission Report (New York: City of New York, 1994); F. R. Morris, Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into certain Gardia in the Donegal Division (Belfast: Government of Ireland 2004).

Volume 5, Number 3 (Spring 2009)

- 121 -

Charl Crous

Policy Design Challenges

The formal development of policy and guidelines governing policeHS relationships are quite a recent development in most English-speaking 12 countries. Policy governing the relationship between police and sources needs to strive towards developing ethical standards and procedures to enhance the impact HS information can have on crime reduction. However, the high-risk nature of the relationship poses certain challenges for policy design. The main challenge is for police to ensure the transformation of a traditional reactiveinvestigative use of informers to a professional proactive focus where sources are managed to enrich police knowledge of the criminal environment so as to ensure crime reduction. This transformation process has been evolving over the last few years as unethical HS practices in police organisations have been exposed. During the Wood Royal Commission of Inquiry into the New South Wales Police, Justice Wood found the relationships between New South Wales police officers and the informers they interacted with to be unethical and in certain cases corrupt. As late as 2004 the Kennedy Royal Commission investigating corruption in the Western Australia Police found that, despite significant work done in the area of structured HSM, some significant breaches of protocol and inadequate operational focus occurred when police engaged with sources. Both the Wood Royal Commission and the Kennedy Commission emphasised the need to ensure that police at all times have a structured, well-supervised system governing HSM at all levels in the organisation. Such a system always has to provide for a tiered management structure. Mollen identified similar requirements during a commission of inquiry into 13 corruption in the New York Police Service, and the same requirement was 14 recently again emphasised by the Morris Tribunal in Ireland. Research shows that police officers have a propensity to condone certain criminal acts by the sources they engage with, and that some relationships

Greer, Towards a sociological model of the police informant, points out that a mere thirty years ago, the informantpolice officer relationship was informal, unstructured and very individualised. During the 1970s, some UK police agencies moved towards the first formal attempt to engage with criminal informants in a more structured way. During that period the UK media came up with the term supergrass to refer to those offenders who were prepared to break the code of silence associated with the underworld and offer their testimony in high-level prosecutions. The supergrass system was established in the United Kingdom after a dramatic rise in organised crime during the 1970s. In Ireland a similar system was introduced and institutionalised during the 1980s as the intelligence systems of the Irish police matured throughout the previous decades. The supergrass system spearheaded the contemporary use of criminal informants as part of a sophisticated police intelligence-gathering system in order to present evidence in court with the aim of convicting large numbers of suspects. 13 Mollen, Commission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption and the Anti-Corruption Procedures of the Police Department: Commission Report. 14 Morris, 'Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into certain Gardia in the Donegal Division.

- 122 -

Security Challenges

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

between officers and their sources are characterised by manipulation and the selective dissemination of information by the police officers handling 15 these informants. Until quite recently police organisations have not made any substantial attempt to manage or regulate the relationship between police and sources or attempted to govern more effectively the process of information gathering by them. It has only been during the last decade that police organisations, particularly in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada, have promulgated policy and processes to re-evaluate and redesign a largely unstructured or even 16 unethical relationship between police and sources. An ethical and professional framework of HSM implies the deployment of sources against pre-set targets identified by strategic assessments and formal intelligence requirements. Such a framework also emphasises that all sources be formally registered with police. The policy governing this relationship between police and sources also needs to direct how these assets are to be protected and managed in a transparent and auditable manner. The policy also has to prescribe the nature of the interaction between those responsible for the management of the sources (the police handlers) and the sources. Policy governing HSM in policing needs to focus on transforming this relationship from being reactive and characterised by the passive reception of information by individual detectives to a proactive approach of integrating a professional HSM framework into the organisations intelligence doctrine and linked to the strategic framework in which the organisation operates. The aim of such a framework should always be to increase the knowledge base of the criminal environment so that police can keep local communities safe while reducing crime and victimisation. This is a paradigm shift which requires a range of different thought patterns within the policing organisation. Part of the modernisation of HSM is that the process pertains to an intelligence-driven strategy across the organisation.

Cooper and Murphy, Ethical Approaches for Police Officers when Working with Informants in the Development of Criminal Intelligence in the United Kingdom; Norris and Dunningham, Some Ethical Dilemmas in the Handling of Police Informers: Billingsley, Process Deviance and the Use of Informers: The Solution'; Rosenfield, Jacobs and Wright, Snitching and the code of the street. 16 Surrey Police, Managing Informants and Contacts: Force Policy Document; New Zealand Customs Services, 'Policy on the New Zealand Customs Service Registered Informant Programme'; New Zealand Police, Informer Policy and Guidelines; Victoria Police, Chief Commissioner's Instruction: Informer Management Policy; Tasmania Police, Informant Management Policy Document; Queensland Police, 'Draft Policy and Procedures State Informant Management System (SIMS); New South Wales Police, NSW Police Informant Management; South Australia Police, Human Source Management: General Order (Adelaide: State Intelligence Branch, September 2005); An Garda Siochana, Code of Practice for Garda Personnel Involved in the Management and Use of Covert Human Intelligence Sources; Los Angeles Police, Informant Manual.

15

Volume 5, Number 3 (Spring 2009)

- 123 -

Charl Crous

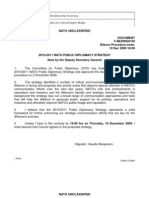

Table 1 indicates eight key differences between a traditional police officer informer relationship and that of a modernised professional and ethical HSM regime. Table 1 also shows the relationship evolving from a traditional policeinformer regime normally managed by local detectives to a formal professional HSM regime driven by a formal intelligence strategy in the organisation.

Table 1: Synopsis of the evolution of HSM in contemporary policing Traditional policeinformer regime Informal informerpolice officer practices Formal professional HSM regime Modernised, formal, professional and ethical HS practices A proactive intelligence-led policing practice to support intelligence assessment which is used for decision making on resource deployment Systematic organisation of HS recruitment, management and tasking according to standards set in the organisation and aligned to intelligence requirements Formal tasking of informants based on a set of intelligence requirements derived from a range of intelligence products Formal registration requirements; motivational and risk assessments of the HS; centrally monitored and governed Tasking and coordination of informants according to formal intelligence requirements based on strategic assessments Information obtained is part of a structured intelligence management system, including analyses and dissemination, for effective decision making; clear supervision and accountability governed by policy Recruiting sources with specific skills and attributes to target specific entities identified by a set of intelligence requirements; the role is performed by well-trained HS handlers and in some cases by full-time HS handlers who are part of dedicated source handling units Formal management regime with a set of determined processes and defined ethical practices, including registration requirements; formal roles of the registrar, the handler, the controller, co-handlers formulated

Reactive technique used by detectives and limited to specific investigations

Reliance on police officer personality and the interactivity of the police officer with a potential informer Individualistic and unstructured nature of the relationship Uncoordinated management and informal personalised management regime established by the police officer and the informer Selective information provided by informants

Selective action by police handlers and a reluctance to act against bad informants

Recruitment of any person by any police officer that presents as a potential informant

Individualised and personalised network of informants with handler individually engaging with informants

- 124 -

Security Challenges

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

There are considerable incentives for a police organisation to develop HSM 17 practices as a core element of the organisations intelligence framework. Contemporary development of professional HSM practices is directly in contrast to the traditional approach whereby the informerpolice officer relationship relied heavily upon the personality and capacity of the individual police officer who owned the informer. Professional practice stipulates that sources be an intelligence asset aligned with the police organisationthe individual preferences of handlers not being a strong consideration at all. The most significant development in modernised HSM practices has been 18 the introduction of formal tasking and directing of sources. Tasking sources entails providing them with a target to provide information on. Targets can be individual offenders or crime groups. The HS is expected to gather information on the target. The objective of tasking the HS is to discover, in a structured formal manner, more information and build knowledge about the targets activities for police to act against the target in some form, be it by way of arrest or disrupting the criminal activity of a crime group. Policy design for ethical and professional HSM practices needs to have some key generic elements. Firstly, the aim of HSM policy and processes is to enhance the intelligence process and, more specifically, police knowledge of the environment. For this reason, the information management regime regarding HSM is normally centralised. The HSM policy should also govern the way in which the tasking of sources occurs as well as govern the process of timely dissemination of intelligence obtained from such sources. A sound HSM regime needs to strive towards meeting organisational objectives in terms of crime reduction. It also needs to provide for performance reviews of the HSM system and practices, including a review of resources available to the organisation to effectively and ethically manage this type of activity. Policy also needs to guide police towards cultivating sources with particular skills or attributes to undertake specific tasks relating to crime reduction 19 priorities. A broad framework to structure the police generally consists of the following dimensions:

17 Cooper and Murphy, Ethical Approaches for Police Officers when Working with Informants in the Development of Criminal Intelligence in the United Kingdom. 18 Innes, Professionalizing the Role of the Police Informant: The British Experience. 19 Surrey Police, Managing Informants and Contacts: Force Policy Document: New Zealand Customs, 'Policy on the New Zealand Customs Service Registered Informant Programme'; New Zealand Police, Informer Policy and Guidelines; Victoria Police, Chief Commissioner's Instruction: Informer Management Policy; Tasmania Police,Informant Management Policy Document; New South Wales Police, NSW Police Informant Management; South Australia, Human Source Management: General Order; An Garda Siochana, Code of Practice for Garda Personnel Involved in the Management and Use of Covert Human Intelligence Sources; Los Angeles Police, Informant Manual.

Volume 5, Number 3 (Spring 2009)

- 125 -

Charl Crous

Setting Objectives: The management objectives for managing the HS are derived from intelligence requirements set in advance. These intelligence requirements are derived from intelligence assessments or flow from other intelligence estimates. Identifying the Target: Targets for the HS are determined in a structured way using the intelligence management process. Sources are then carefully assessed to match the best potential source to the most appropriate target. Surveying the Target: Before a potential HS is proactively tasked to target a specific person, group or network, a detailed assessment is carried out on the target. Assessing and Evaluating the Sources Potential: Police identify the most suitable person to engage with as an HS. A person is evaluated based on his or her level of access to a target, offender or group, or the relationships this person already has with such an 20 offender or group. Once police have identified the potential informant, an assessment needs to be carried out on the potential HS, including a detailed risk assessment. The motivation of the person to be registered as an HS must be established at all times as the persons motivational factors determine the nature of the relationship between police and source.

A professional HSM system has various advantages for policing, including: effective and ethical mechanisms to engage with sources and effective information management; improved understanding of the criminal environment on area, district, regional and national levels supporting sustained crime reduction and community safety, while building police capability to disrupt the criminal environment; clear accountability arrangements at all levels of the process; increased intelligence at area, district, regional and national levels for effective decision making and effective and efficient deployment of resources according to risk at all levels;

20

Once police have assessed the target in detail, they need to determine and identify which people have access to the target. The potential HS might be an associate of a high profile offender. Police will then have to devise a strategy on how to approach and ultimately engage the potential source in a long-term relationship with police (recruitment and registration) in order to provide intelligence on the target (person, offender, location or criminal network).

- 126 -

Security Challenges

Human Intelligence Sources: Challenges in Policy Development

identification of intelligence gaps at all levels and mitigation of organisational and community risks in terms of criminality level; an enhanced district-wide focus on crime reduction in general but also providing a focus on police interventions aimed at high risk communities or networks of high risk offenders; and contribution to the development of intelligence best practice and a focus on organisational ethics and integrity.

Conclusion

There are clearly a range of risk factors associated with the relationship police form with those active in the criminal environment, as was seen with the commissions of inquiry held in the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States. The relationship between police and those in the community willing to provide information will continue and, in fact, need to continue to secure communities and to reduce crime. Police organisations will be in a much stronger position when they formally recognise the relationship between police and those in the criminal environment who are able to work with police and when police develop policy governing a professional ethical framework to manage this relationship. The challenge for police is to ensure that the shackles of past behavioura reactive, individually-driven, unstructured engagement with informersmake way for a coordinated, proactive, systematic management system that provides protection for both sources and their handlers in a modern policing environment. A truly professional and ethical system will be integrated into the organisations formal intelligence framework and not be centred on individual relationships between police officers and informers. The HSM policy that governs the relationship between police and sources must be transparent, ensuring reporting of contacts and interaction between supervisors and sources, and the tasking and coordination of sources should be based on intelligence requirements identified by strategic assessments. The modernisation of HSM systems will improve the quality of intelligence management at all levels in policing from local command level to the international policing domain.

Charl Crous is the Policing Development Manager for Auckland Metro Crime and Operations Support (AMCOS) and chaired the CHIS working group of the New Zealand Police which reviewed the policy on criminal informers in the New Zealand Police. charl.crous@police.govt.nz. .

Volume 5, Number 3 (Spring 2009)

- 127 -

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Civil Procedure I Outline Explains Basic Principles and Rules of PleadingDocument31 pagesCivil Procedure I Outline Explains Basic Principles and Rules of PleadingAshley DanielleNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Micro-Participation The Role of Microblogging in Urban PlanningDocument38 pagesMicro-Participation The Role of Microblogging in Urban Planningshakes21778No ratings yet

- Automated License Plate Reader Systems - Policy and Operational Guidance For Law EnforcementDocument128 pagesAutomated License Plate Reader Systems - Policy and Operational Guidance For Law Enforcementshakes21778No ratings yet

- Obama Is Officially Charged With TREASONDocument58 pagesObama Is Officially Charged With TREASONlicservernoida0% (1)

- Informal International Police NetworksDocument205 pagesInformal International Police NetworksFrattaz100% (2)

- Who Watches The WatchmenDocument310 pagesWho Watches The Watchmen...tho the name has changed..the pix remains the same.....No ratings yet

- Sense MakingDocument233 pagesSense Makingshakes21778100% (1)

- Imperial SecretsDocument248 pagesImperial Secretsshakes21778100% (1)

- Threat Anticipation ProjectDocument7 pagesThreat Anticipation Projectshakes21778No ratings yet

- The Creation of The National Imagery and Mapping AgencyDocument121 pagesThe Creation of The National Imagery and Mapping Agencyshakes21778No ratings yet

- Managing The Private SpiesDocument90 pagesManaging The Private Spiesshakes21778100% (2)

- US State Dept Counterintelligence ProgramDocument19 pagesUS State Dept Counterintelligence Programshakes21778No ratings yet

- Attaché ExtraordinaireDocument196 pagesAttaché Extraordinaireshakes21778No ratings yet

- Culture Matters The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook PDFDocument266 pagesCulture Matters The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook PDFshakes21778No ratings yet

- Shooting The FrontDocument33 pagesShooting The Frontshakes21778100% (1)

- US National Counterterrorism Strategy, 2011Document26 pagesUS National Counterterrorism Strategy, 2011shakes21778No ratings yet

- Allegiance in A Time of GlobalizationDocument63 pagesAllegiance in A Time of Globalizationshakes21778No ratings yet

- Future of America's Forest and Rangeland.Document218 pagesFuture of America's Forest and Rangeland.shakes21778No ratings yet

- 9 Ways To Make Green Infrastructure Work in CitiesDocument32 pages9 Ways To Make Green Infrastructure Work in Citiesshakes21778No ratings yet

- Joint Publication 3-13.3 Operations SecurityDocument75 pagesJoint Publication 3-13.3 Operations Securityshakes21778No ratings yet

- Federal Highway Administration Freight and Land Use HandbookDocument138 pagesFederal Highway Administration Freight and Land Use Handbookshakes21778No ratings yet

- Nato Io PolicyDocument14 pagesNato Io Policyshakes21778No ratings yet

- NATO PublicDiplomacy 2011Document11 pagesNATO PublicDiplomacy 2011shakes21778No ratings yet

- Cyberculture and Personnel SecurityDocument184 pagesCyberculture and Personnel Securityshakes21778No ratings yet

- Joint Publication 3-13.2 Military Information Support OperationsDocument108 pagesJoint Publication 3-13.2 Military Information Support Operationsshakes21778No ratings yet

- Use of Internet For Terrorist PurposesDocument158 pagesUse of Internet For Terrorist PurposesDuarte levyNo ratings yet

- Devenney CaptGadeDocument10 pagesDevenney CaptGadeshakes21778No ratings yet

- (JCS-MILDEC) Military Deception - Jan 2012Document81 pages(JCS-MILDEC) Military Deception - Jan 2012Impello_TyrannisNo ratings yet

- Zelikow Reflections On Reform 18sep2012Document20 pagesZelikow Reflections On Reform 18sep2012shakes21778No ratings yet

- Attention! Rumor Bombs, Affect, Managed Democracy 3.0Document26 pagesAttention! Rumor Bombs, Affect, Managed Democracy 3.0shakes21778No ratings yet

- The 2012 Wisconsin Gubernatorial Recall Twitter CorpusDocument7 pagesThe 2012 Wisconsin Gubernatorial Recall Twitter Corpusshakes21778No ratings yet

- Twitter Zombie GroupDocument10 pagesTwitter Zombie Groupshakes21778No ratings yet

- Aphra BehanDocument4 pagesAphra Behansushila khileryNo ratings yet

- Hassan El-Fadl v. Central Bank of JordanDocument11 pagesHassan El-Fadl v. Central Bank of JordanBenedictTanNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Civrev 1 Minority InsanityDocument6 pagesCase Digests Civrev 1 Minority InsanityredrouxNo ratings yet

- 1920 SlangDocument11 pages1920 Slangapi-249221236No ratings yet

- RADICAL ROAD MAPS - The Web Connections of The Far Left - HansenDocument288 pagesRADICAL ROAD MAPS - The Web Connections of The Far Left - Hansenz33k100% (1)

- Rule 14 Cathay Metal Corporation vs. Laguna West Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc. G.R. No. 172204. July 2, 2014Document16 pagesRule 14 Cathay Metal Corporation vs. Laguna West Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc. G.R. No. 172204. July 2, 2014Shailah Leilene Arce BrionesNo ratings yet

- Diana Novak's ResumeDocument1 pageDiana Novak's Resumedhnovak5No ratings yet

- Resolving Construction DisputesDocument47 pagesResolving Construction DisputesJubillee MagsinoNo ratings yet

- BELARUS TV GUIDEDocument17 pagesBELARUS TV GUIDEДавайте игратьNo ratings yet

- CG Power and Industrial Solutions LimitedDocument27 pagesCG Power and Industrial Solutions LimitedMani KandanNo ratings yet

- Luna vs. RodriguezDocument1 pageLuna vs. RodriguezMP ManliclicNo ratings yet

- Delhi To Indore Mhwece: Jet Airways 9W-778Document3 pagesDelhi To Indore Mhwece: Jet Airways 9W-778Rahul Verma0% (1)

- Module4 Search For Filipino OriginsDocument16 pagesModule4 Search For Filipino OriginsJohn Carlo QuianeNo ratings yet

- Venn Diagram Customs With ReferencesDocument2 pagesVenn Diagram Customs With Referencesapi-354901507No ratings yet

- Ethics LawDocument8 pagesEthics LawDeyowin BalugaNo ratings yet

- WH - FAQ - Chaoszwerge Errata PDFDocument2 pagesWH - FAQ - Chaoszwerge Errata PDFCarsten ScholzNo ratings yet

- Themes of A Passage To India: Culture ClashDocument6 pagesThemes of A Passage To India: Culture ClashGabriela Macarei100% (4)

- Alpha Piper EnglishDocument22 pagesAlpha Piper Englishlohan_zone100% (1)

- Maglasang Vs Northwestern University IncDocument3 pagesMaglasang Vs Northwestern University Incmondaytuesday17No ratings yet

- Republic V BagtasDocument3 pagesRepublic V BagtasLoren SeñeresNo ratings yet

- FIGHT STIGMA WITH FACTSDocument1 pageFIGHT STIGMA WITH FACTSFelicity WaterfieldNo ratings yet

- Corporate Scam in IndiaDocument5 pagesCorporate Scam in Indiamohit pandeyNo ratings yet

- General PrinciplesDocument60 pagesGeneral PrinciplesRound RoundNo ratings yet

- Salah (5) NawafilDocument12 pagesSalah (5) NawafilISLAMICULTURE100% (2)

- The Nuremburg Code (Wiki)Document4 pagesThe Nuremburg Code (Wiki)Tara AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Asia Pacific Chartering Inc. vs. Farolan G.R. No.151370Document2 pagesAsia Pacific Chartering Inc. vs. Farolan G.R. No.151370rebellefleurmeNo ratings yet

- Thomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Document2 pagesThomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Francisco de Liano, Alberto Villa-Abrille JR and San Miguel Corporation Vs CA and Benjamin Tango GR No. 142316, 22 November 2001 FactsDocument2 pagesFrancisco de Liano, Alberto Villa-Abrille JR and San Miguel Corporation Vs CA and Benjamin Tango GR No. 142316, 22 November 2001 FactscrisNo ratings yet