Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Deep Neck Abscesses and Life-Threatening Infections of The Head and Neck

Uploaded by

Robel Mae Lagos MontañoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Deep Neck Abscesses and Life-Threatening Infections of The Head and Neck

Uploaded by

Robel Mae Lagos MontañoCopyright:

Available Formats

TITLE: Deep Neck Abscesses and Life-Threatening Infections of the Head and Neck SOURCE: Grand Rounds, Dept

of Otolaryngology UTMB DATE: February 25, 1998 RESIDENT: Carl Schreiner, MD FACULTY PHYSICIAN: Francis B. Quinn, MD SERIES EDITOR: Francis B. Quinn, Jr. MD

|Return to Grand Rounds Index|

"This material was prepared by resident physicians in partial fulfillment of educational requirements established for Postgraduate Medical Education activities and was not intended for clinical use in its present form. It was prepared for the purpose of stimulating group discussion in a conference setting. No warranties, either express or implied, are made with respect to its accuracy, completeness, or timeliness. The material does not necessarily reflect the current or past opinions of subscribers or other professionals and should not be used for purposes of diagnosis or treatment without consulting appropriate literature sources and informed professional opinion." INTRODUCTION Life-threatening infections of the head and neck are much less common since the introduction of antibiotics and mortality rates are lower. The widespread use of antibiotics has not only lowered the incidence of life-threatening infections but has also altered their clinical presentation. Obvious signs of systemic toxicity, such as chills and spiking fevers and classic presentations of infectious syndromes may be lacking in patients with partially treated infections. This, combined with the increasing number of patients with severe immunosupression makes it worthwhile for the physician to review these syndromes and the unique anatomic features of the head and neck which can lead to life-threatening complications. HEAD AND NECK ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS The most common sources of life-threatening soft tissue infections of the head and neck are the dentition and tonsils. Most infections are polymicrobial and the responsible bacteria are often normal flora (Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Actimomyces, Fusobacterium and microaerophilic strep.) that become virulent and invasive when normal barriers are broken (ie. tonsillitis, dental abscess, trauma). Obligate anaerobes frequently outnumber the anaerobes by a factor of 10:1 and synergistic effects often promote invasiveness. From these sites, infection may spread

along facial planes, which serve to either separate or connect distant sites by limiting or directing the spread of infection. The most common sources for intracranial complications are the nose, sinuses and ear, which all have unique pericranial and periorbital locations. Infection from these sites may spread either through direct extension through bone or through retrograde venous spread. The following discussion will review the clinical patterns of deep neck space infections and summarize the parameningeal or intracranial complications of head and neck infections. DEEP NECK SPACE AND SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS Deep neck space infections are most commonly odontogenic in origin. The vast majority of dental infections are treated with root canal, extraction or periodontal therapy before they become serious. However, a small number of infections follow a fulminant course and may become life-threatening either through airway compromise, necrotizing fascitis, or rapid spread to involve the orbit, cranium or chest. Dierks et. al. found, in their review of fulminant odontogenic infections, that most cases involved delayed treatment of molar infections. Anaerobic infections predominated and most patients were young and without debilitating medical conditions. Before discussing individual fascial compartments of the neck, a brief review of the cervical fascial layers is necessary (2,3). Fascial compartments of the neck are potential spaces between layers of fascia. The cervical fascia is divided into two main compartments; the superficial cervical fascia and the deep cervical fascia. The superficial cervical fascia lies just below the skin, envelopes the platysma and muscles of facial expression, and completely surrounds the neck. The deep cervical fascia is subdivided into superficial, middle, and deep layers. The superficial (investing) layer of the deep cervical fascia invests the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, strap muscles, parotid and submandibular glands. The middle (visceral) layer surrounds the thyroid gland, esophagus and trachea. Its upper limit attaches to the hyoid bone and it extends inferiorly into the mediastinum. The deep layer of the deep cervical fascia splits into prevertebral and alar layers. The prevertebral layer lies immediately adjacent to the vertebral bodies and extends from the skull base to the coccyx. The alar layer is located just anterior to the prevertebral layer but extends only to the level of the second thoracic vertebra. All three layers of the deep cervical fascia contribute to the carotid sheath so that infection of any layer may spread directly to involve the great vessels of the neck, whick have direct communication to the chest. Submandibular Space The prototypical infection of this space was described by Wilhelm von Ludwig in 1836. He described a gangrenous infection of the neck with woody cellulitis without

suppuration and insidious asphyxiation. With minor changes, his definition still holds today although the term Ludwigs angina implies bilateral submandibular space involvement. The submandibular space extends from the hyoid bone to the mucosa of the floor of the mouth. It is bound anteriorly and laterally by the mandible and inferiorly by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. The mylohyoid muscle acts as a sling across the mandible and divides the submandibular space into sublingual and submylohyoid spaces. Because these spaces communicate freely around the posterior border of the mylohyoid, some feel they should be considered as a single unit, the submandibular space. Again, the definition of Ludwigs angina requires bilateral submandibular (including sublingual) space involvement. The mylohyoid muscle also plays a key role in determining the direction of spread of dental infections. It attaches to the mandible at an angle, leaving the apices of the second and third molars below the mylohyoid line and the apex of the first molar above. Most apical molar infections perforate the mandible on the lingual side, so if the tooth apex is above the mylohyoid line it will involve the sublingual space. If it perforates below the mylohyoid line is involves the submylohyoid space. The bucopharyngeal gap is a potentially dangerous connection between the submandibular and lateral pharyngeal spaces that is created by the styloglossus muscle as is passes between the middle and superior constrictors. Due to this connection, cellulitis of the submandibular space can directly spread to the lateral pharyngeal space, which, as will be discussed, is a more dangerous space for infection. Most patients with submandibular space infections are young, healthy adults with an odontogenic infection. Patients usually present with mouth pain, dysphagia, drooling and stiff neck. In the case of Ludwigs angina, massive tongue and floor of mouth edema can rapidly lead to posterior and superior displacement of the tongue as well as anterior displacement out the mouth. The patient often maintains the neck in an extended position and may have a muffled or "hot potato" voice. The neck shows a characteristic erythematous woody swelling but fluctuance is usually absent. Trismus, which indicates lateral pharyngeal or masticator space involvement, should be absent in isolated submandibular space infections. The most common cause of death in Ludwigs angina is asphyxia. Airway control is the first priority of treatment, followed by intravenous antibiotics and timely surgical drainage. The method of controlling the airway in Ludwigs angina is controversial and may include close observation, tracheotomy, fiberoptic intubation or cricothyroidotomy. Airway control is not always needed with close observation in an

ICU. Blind oral or nasotracheal intubation or attempts with neuromuscular paralysis is contraindicated in Ludwigs angina as they may precipitate an airway crisis. Tracheotomy is still the most widely used method of airway control but some authors feel the risk of aspiration pneumonia (from close proximity of the trach site to open neck wounds)and the risk of mediastinal infection as reasons to avoid tracheotomy if possible. Cricothyroidotomy is usually not a good option with in patients with massive neck edema. Penicillin has long been the drug of choice in the treatment of deep neck space infections but there appears to be a trend of increasing beta-lactamase producing organisms (particularly Bacteroides) so broader spectrum antibiotics are needed. In cases of critically ill patients or a poor response to therapy, clindamycin or metronidazole may be added, but neither drug should be used alone. Antibiotic therapy alone may be curative in the cellulitic phase but failure to respond to intravenous antibiotics may ether be due to undrainied purulent collections or extension into adjacent spaces. Surgical drainage was once universally required but now may be reserved for cases where antibiotic treatment fails or when soft tissue air or pus is noted. Intraoral drainage may be adequate in a few cases of limited sublingual involvement but drainage through submandibular incisions with splitting of the mylohyoid muscle is usually required. If the infection is odontogenic, the offending tooth should also be removed. Lateral Pharyngeal Space This space (also called the parapharyngeal space) occupies a critical area in the neck, as it communicates with all other fascial spaces. It sits as an inverted cone with its base at the base of skull and apex at the hyoid bone. Its posterior boundary is the prevertebral fascia and its anterior boundary is the raphe junction of the buccinator and superior constrictor muscles. It is bound laterally by the mandible and the parotid fascia, which is often noncontiguous over the parotid, allowing communication between the parotid and the lateral pharyngeal space. The lateral pharyngeal space can be divided into anterior (prestyloid) and posterior (retrostyloid) compartments by the styloid process. The anterior compartment contains only fat, lymph nodes and muscle. The posterior compartment contains the carotid and internal jugular vessels, as well as cranial nerves IX through XII. Infections of the anterior space present with pain, fever, neck swelling below the mandible and trismus. The source if the infection is again most often dental, but may arise from numerous sources, including the tonsils, parotid, and submandibular, peritonsilar, masticator, or retropharyngeal spaces. Rotation of the neck away from the

side of swelling causes severe pain from tension on the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle. Ominous signs of posterior involvement include Horners syndrome, CN IX through XII palsies and complications include septic jugular thrombophlebitis (most common) and carotid artery erosion or thrombosis. Sentinel bleeds, or recurrent bleeding from the nose, mouth or ear should always alert the physician of the possibility of an impending carotid rupture. Hematogenous dissemination can also occur with major vessel involvement. Airway impingement due to medial bulging of the pharyngeal wall and supraglottic edema can occasionally occur but is much less likely than in Ludwigs angina. The treatment of lateral pharyngeal abscess is similar to the treatment of Ludwigs angina except that surgical drainage is usually required and frank purulence is more often encountered in lateral pharyngeal abscesses. CT scanning is the imaging modality of choice and is helpful in confirming which compartments are involved. In complicated cases such as septic jugular vein thrombosis, several weeks of intravenous antibiotics may be required. Resection of the thrombosed internal vein is now rarely performed except in refractory cases. Retropharyngeal, Danger, And Prevertebral Spaces The retropharyngeal, danger and prevertebral spaces all lie between the deep cervical fascia surrounding the pharynx anteriorly and the spine posteriorly. The retropharyngeal space is bordered anteriorly by the constrictor muscles and posteriorly by the alar layer of the deep cervical fascia. Infections of this space can extend down to the superior mediastinum. These infections most commonly occur in children as a complication of suppurative adenitis. Presenting symptoms include fever, stiff neck, drooling and dysphagia. Bulging of the posterior pharyngeal wall is often difficult to appreciate. Properly performed lateral neck films in extension will show thickened prevertebral soft tissue but a CT scan is essential to determine the inferior limits of involvement. Retropharyngeal abscesses should be considered the most dangerous deep neck space abscess because complications include supraglottic edema with airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia due to rupture of the abscess and acute mediastinitis. Mediastinitis is the most feared complication and may result in empyema or pericardial effusions. If the infection perforates the alar layer posteriorly, it enters the danger space, which extends down the entire mediastinum to the level of the diaphragm. Further extension posteriorly enters the prevertebral space, which extends down to the coccyx. Treatment involves intravenous antibiotics and timely surgical drainage. Recent reports have shown good responses to conservative therapy so a trial of antibiotics prior to surgical drainage may be indicated. Surgical drainage should be performed in the operating room via a transoral approach with the head down to prevent rupture during intubation and septic aspiration.

Masticator Space The masticator (or masseteric space) contains the pterygoid and masseter muscles as well as the insertion of the temporalis muscle on the coronoid process of the mandible. It communicates freely with the temporal space superiorly but not usually to the adjacent more dangerous spaces. Most masticator space infections are caused by molar teeth and trismus is the most pronounced clinical feature and often precludes intraoral examination. CT is invaluable in the assessment of masticator space infections as it can often influence the surgical approach and distinguish abscess from cellulitis. Intraoral approaches are often sufficient for simple masticator space abscesses but an external approach may be required cases with extension to other spaces. Peritonsillar Abscess Peritonsillar abscess is a complication of acute tonsillitis that is rarely life- threatening in itself but, as previously discussed, can spread to involve the lateral pharyngeal space. Ther peritonsillar space is a potential space of loose areolar tissue that surrounds the tonsil and is bounded laterally by the superior constrictors. Most abscesses occur in younger patients who present with fever, sore throat and dysphagia. Treatment options include serial aspiration, local incision and drainage or surgical drainage with tonsillectomy. Local incision and drainage in the emergency room after intravenous fluid replacement and intravenous antibiotics is our method of treatment. Unless severely dehydrated or unable to tolerate fluids, the patient usually does not require admission. Necrotizing Fasciitis Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck is a progressive, polymicrobial, synergistic infection of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. Devastating facial necrosis and severe systemic toxicity and death can rapidly occur if left untreated. In general, due to its abundant vascular supply, the head and neck is rarely (compared to the trunk and extremities) involved and is often associated with diabetes or severe vascular disease. Again, dental infections are the most common source. Spankus, in his review of craniocervical necrotizing fascitis, found that involvement of the galea aponeurotica following trauma with extension into the neck to be relatively common. Most infections spread along fascial planes without any obvious skin involvement initially, but crepitance, skin anesthesia, purple discoloration and bullae may later form. The presence of necrosis is a key diagnostic point and is suggested by air or creptance in the soft tissues, failure of the infection to respond to antibiotics and dusky blue skin over the effected area. It is also important to realize that skin changes are a late sign of necrosis and significant soft tissue necrosis can occur with normal

overlying skin Radical surgical resection of all necrotic skin and soft tissue with intravenous antibiotics are essential, along with correction of any underlying systemic abnormalities. Skin grafting is often required initially to promote wound closure. Antibiotic coverage should include a pencillinase-resistant penicillin (to cover emerging resistant strains of Bacteroides) plus an aminoglycoside or third generation cephalosporin. The most commonly isolated organisms include anaerobes, streptococcus sp., S. aureus, bacteroides and occasionally clostridia. Gas formation is characteristic of clostridial infections but involvement of the neck is actually very rare and the presence of air in the neck does not always indicate infection. Air in the neck can be caused by surgical manipulation, trauma or air dissection from adjacent sites (i.e. chest) In general, necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck is a surgical emergence with a mortality rate of 22% in the head and neck if not treated aggressively. Acute Supraglottitis Although not a deep neck space infection, supraglottitis, is obviously considered lifethreatening due to potential airway compromise. Supraglottitis is a more appropriate term than epiglottis because isolated involvement of the epiglottis is rare. Although much less common after the development of H. influenzae type b vaccines, acute supraglottitis in children does still occur and prompt treatment can be life-saving. The typical child presents with a muffled (not hoarse) voice, fever, drooling and stridor. The stridor is usually most pronounced on inspiration and the child tends to maintain an upright position with the neck extended. Rapid inspiration tends to collapse the already edematous epiglottis so respirations are usually slow and deliberate. Once the diagnosis is suspected, further attempts to examine the child, especially fiberoptic examination should be avoided and the child should be taken to the operating room for airway control. Plain films of the neck will show an enlarged epiglottis but radiologic examination should not precede airway control in suspected cases. The child should escorted to the operating room with a skilled physician present at all times as the clinical course can rapidly worsen without warning. Controlled intubation should be performed in the operating room with available bronchoscopic and tracheotomy equipment. Conversion to a nasotracheal tube is usually felt to be a lower risk for extubation in the intensive care unit. Treatment should then include intubation and intravenous antibiotics in an ICU setting with controlled extubation in the operating room following the resolution of the infection and edema. LIFE THREATENING SINONASAL INFECTIONS Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis

Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis is a rapidly progressive invasive infection of the paranasal sinuses by fungi from the Mucoraceae family, which includes Absidia, Mucor, Rhizomucor and Rhizopus. These organisms ore ubiquitous and disseminated by aerosolized spores. Fulminant infections occur primarily in severe diabetics and the immunocompromized. The relationship of hyperglycemia and macrophage dysfunction has been proposed as an explanation for the involvement of diabetics. The fungi are vasculotropic an tend to grow along vessels, causing severe necrosis. Infection may extent intracranially through the thin cribiform plate, leading to meningitis or intracranial abscess formation. Clinically, the initial lesions appear as black necrotic areas involving the nasal mucosa or palate. Orbital involvement is characterized by ophthalmoplegia, proptosis, chemosis and eventual visual loss. Intracranial extension is suggested by headache, cranial nerve palsies, seizures or meningeal signs. Computerized tomography often shows opacificatioin of the involved sinuses and bone erosion or destruction. Early surgical debridement to normal bleeding tissues is mandatory and the diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of broad, nonseptate hyphae branching at right angles. Once invasion is confirmed, high dose amphotercin is also administered. Early recognition and surgical debridement has greatly improved the mortality rates fir this once almost uniformly fatal disease. Complications of Paranasal Sinusitis The anterior cranial fossa forms the roof of the ethmoid sinuses and the posterior wall of the frontal sinuses. This unique parameningeal location leads to several potential intracranial complications from sinusitis. Due to its location, direct extension from the maxillary sinus to vital structures is rare. Frontal or ethmoid sinusitis can lead to meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural empyema, or frontal lobe abscess. Frontal sinusitis can lead to thrombosis of the superior sagital venous sinus. The sphenoid sinus is surrounded by the pituitary gland, optic nerve and chiasm, internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus. Sphenoid sinusitis can spread to cause cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, temporal lobe abscess, and the superior fissure symdrome. The superior orbital fissure syndrome is characterized by orbital pain, proptosis and ophthalmoplegia (cranial nerves III, IV and VI) and numbness of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Cavernous sinus thrombosis has similar findings but signs of venous congestion (chemosis, proptosis, eyelid edema and retinal findings) are more prominent and vision loss due to involvement of the ophthalmic vein may occur. Less life-threatening but severe complications can arise from periorbital or retroorbital eye involvement (through penetration of the paper-thin lamina paprycia) or frontal osteomyelitis (Potts puffy tumor). In Clayman's review of intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis, frontal lobe abscess was the most common complication, followed by meningitis, subdural empyema and cavernous sinus

thrombosis. The most common presenting symptoms were related to increased intracranial pressure and included fever, headache, lethargy and seizure. Negative cultures for both anaerobes and anaerobes were common, likely reflecting prior antibiotic treatment. High resolution CT is the imaging study of choice and treatment requires gram-positive and anaerobic antibiotic coverage and timely surgical intervention. Complications of Otologic infections Infections the middle ear and mastoid can extend into the middle cranial fossa to involve the temporal lobe or the posterior cranial fossa to involve the cerebellum. Although the incidence of intracranial complications in patients with chronically draining ears is likely extremely low, Schwaber et. al. found the presence of purulent malodorous ear drainage, fever and headache to be warning signs of an impending intracranial complication in a patient with a "chronic ear." Half of the patients had a visible cholesteatoma on exam. The most common complication was epidural abscess, followed by meningitis and brain abscess. Lateral sinus septic thrombosis can also occur and should be suspected if persistent spiking fevers occur postoperatively. Other warning signs of an intracranial complication include vestibular symptoms or hearing loss and facial paralysis. The management of subdural empyema can be particularly challenging, as it can occur as a complication of meningitis, sinusitis or otomastoiditis. The treatment often requires a combined otolaryngology and neurosurgical approach for proper drainage. Malignant otitis externa is a necrotizing pseudomonal infection of the external ear canal that occurs almost exclusively in the severely debilitated or diabetic. An external ear infection spreads through the junction of the cartilaginous and bony junction of the ear canal to the base of the skull. Clinically, it presents as severe otalgia, purulent ear drainage and the formation of granulation tissue or a polyp at the junction of the bony and cartilaginous ear canal. Multiple cranial nerve palsies including facial paralysis may ensue. The diagnosis is confirmed with positive technetium (bone) and gallium scans and treatment includes local debridement and long-term antibiotic therapy until the gallium scan clears. --------------------------------------------------------------A neck abscess is a collection of pus in the neck. Typically, the abscess is caused by an infection. As the pus continues to accumulate, the abscess will grow larger and form a mass. This can create other significant problems. Uncommonly large neck abscesses can push on other structures in the neck, such as the throat and windpipe, and lead to problems swallowing and breathing. There are many possible causes of a neck abscess. Generally, an infection, commonly in the head or neck can lead to an abscess. An ear infection, the common cold and sinus infections are some common contributors to this condition. Another possible cause is tonsillitis, orinflammation of

the tonsils. If any of these infections extends into the tissues within the neckor throat, an abscess may form. A common type of abscess in the neck is a superficial neck abscess. This type of abscess is typically located right under the skin. It may be caused by an infection in the throat, swollenlymph nodes or a cold. The most common symptom is an irritated throat, which may appear sore, red and swollen. Other symptoms can include a fever, chills, stiffness and pain in theneck and overall feeling unwell.

NCP Nursing Care Plan For Asthma

image courtesy of students.cis.uab.edu

NCP Nursing Care Plan For Asthma.Asthma is a growing health problem, the number of children with asthma has increased markedly, unfortunately, and approximately 75% of children with asthma continue to have chronic problems in adulthood. Asthma is a reversible lung disease that may resolve spontaneously or with treatment, asthma is characterized by obstruction or narrowing of the airways, which are typically inflamed and hyperresponsive to various stimuli. Signs of asthma range from mild wheezing and Dyspnea to life-threatening respiratory failure. Symptoms of bronchial airway obstruction may persist between acute episodes.

Hyper-reactivity leads to airway obstruction due to acute onset of muscle spasm in the smooth muscle of the tracheobronchial tree, thereby leading to a narrowed lumen. In addition to muscle spasm, there is swelling of the mucosa, which leads to edema. Lastly, the mucous glands increase in number, hypertrophy, and secrete thick mucus. In asthma, the total lung capacity (TLC), functional residual capacity (FRC), and residual volume (RV) increase, but the hallmark of airway obstruction is a reduction in ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and the FEV1 to the forced vital capacity (FVC). Although asthma can result from infections (especially viral) and inhaled irritants, it often is the result of an allergic response. An allergen (antigen) is introduced to the body, and sensitizing antibodies such as immunoglobulin E (IgE) are formed. IgE antibodies bind to tissue mast cells and basophils in the mucosa of the bronchioles, lung tissue, and nasopharynx. An antigen-antibody reaction releases primary mediator substances such as histamine and slowreacting substance of anaphylaxis (SRS-A) and others. These mediators cause contraction of the smooth muscle and tissue edema. In addition, goblet cells secrete a thick mucus into the airways that causes obstruction.

Extrinsic and intrinsic asthma For many asthmatics, intrinsic and extrinsic asthma coexist. Intrinsic asthma results from all other causes except allergies, such as infections (especially viral), inhaled irritants, and other causes or etiologies. The parasympathetic nervous system becomes stimulated, which increases bronchomotor tone, resulting in bronchoconstriction. Asthma that results from sensitivity to specific external allergens is referred to as extrinsic (atopic). In those cases where the allergen isn't obvious, asthma is referred to as intrinsic (nonatopic). Allergens that cause extrinsic asthma include pollen, animal dander, house dust or mold, kapok or feather pillows, food additives containing sulfites, and any other sensitizing substance. Extrinsic asthma usually begins in childhood and is accompanied by other manifestations of atopy (type I, immunoglobulin [Ig] Emediated allergy), such as eczema and allergic rhinitis. With intrinsic asthma, no extrinsic allergen can be identified. Most cases are preceded by a severe respiratory tract infection. Irritants, emotional stress, fatigue, exposure to noxious fumes, and endocrine, temperature, and humidity changes may aggravate intrinsic asthma attacks.

Asthma Causes and Treatment Asthma also called chronic reactive airway disease, chronic inflammatory disorder episodic exacerbations of reversible inflammation and hyperreactivity and variable constriction of bronchial smooth muscle, hypersecretion of mucus, and edema. Asthma that results from sensitivity to specific external allergens is known as extrinsic. In cases in which the allergen isn't obvious, asthma is referred to as intrinsic. Extrinsic asthma Allergens include pollen, animal dander, house dust or mold, kapok or feather pillows, food additives containing sulfites, Genetic and environmental: household substances (such as dust mites, pets, cockroaches, mold), pollen, foods, latex, emotional upheaval, air pollution, cold weather, exercise, chemicals, medications, viral infections and any other sensitizing substance. Extrinsic asthma usually begins in childhood and is accompanied by other manifestations such as eczema and allergic rhinitis. In patients with intrinsic (nonatopic) asthma, no extrinsic allergen can be identified. Most cases are preceded by a severe respiratory tract infection. Irritants, emotional stress, fatigue, and exposure to noxious fumes, as well as endocrine changes and changes in temperature and humidity, may aggravate intrinsic asthma attacks. In many patients with asthma, intrinsic and extrinsic asthma coexist. Exercise may also provoke an asthma attack. In patients with exercise-induced asthma, bronchospasm may follow heat and moisture loss in the upper airways.

Treatment for Asthma Treatment of acute asthma aims to decrease bronchoconstriction, reduce bronchial airway edema, and increase pulmonary ventilation. After an acute episode, treatment focuses on avoiding or removing precipitating factors, such as environmental allergens or irritants. Drug therapy is most effective when begun soon after the onset of symptoms. A patient who doesn't respond to this treatment, whose airways remain obstructed, and who has increasing respiratory difficulty is at risk for status asthmaticus and may require mechanical ventilation.

Nursing Diagnosis Asthma Nursing Assessment for patients with asthma. An asthma attack may begin dramatically, with simultaneous onset of many severe symptoms, or insidiously, with gradually increasing respiratory distress. It typically includes progressively worsening shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness or some combination of these signs and symptoms. Patients history, obtain history of allergies thorough description of the response to allergens or other irritants. The patient may describe a sudden onset of symptoms after exposure, with a sense of suffocation. Symptoms include dyspnea, wheezing, and a cough and also chest tightness, restlessness, anxiety, and a prolonged expiratory phase. Ask if the patient has experienced a recent viral infection. Physical examination. severe shortness of breath can hardly speak, patients use their accessory muscles for breathing. Some patients have an increased anteroposterior thoracic diameter. If the patient has marked, color changes such as pallor or cyanosis or becomes confused, restless, or lethargic, increased risk of respiratory failure.

Percussion of the lungs usually produces hyper-resonance, and palpation may reveal vocal fremitus. Auscultation high-pitched inspiratory and expiratory wheezes, prolonged expiratory phase of respiration. A rapid heart rate, mild systolic hypertension, and a paradoxic pulse may also be present.

Diagnostic test for asthma

Pulmonary function tests Pulse oximetry.

NURSINGDIAGNOSIS INTERVENTIONS Evaluate respiratory ineffective Airway rate/depth and breath sounds. Clearance R/T Bronchospasm Increased production of secretions, retained secretions, thick, viscous secretions Decreased energy or fatigue Assist client to maintain a comfortable position.

RATIONALE Tachypnea is usually present to some degree and may be pronounced during respiratory stress. facilitates respiratory function using gravity; however, client in severe distress will seek the position that most eases breathing

EVALUATION Respiratory Status: Airway Patency Maintain patent airway with breath sounds clear or clearing. Demonstrate behaviors to improve or maintain clear airway.

Precipitators of allergic type of respiratory reactions that can trigger or exacerbate onset of acute episode.

Keep environmental free from sources of allergen such as dust, smoke, and feather pillows to a minimum according to individual situation.

To maximize cough effort, lung expansion and drainage, and reduce pain impairment.

Encourage/instruct in deepbreathing and directed coughing exercises

impaired Gas Exchange monitor skin and mucous Duskiness and central R/T Altered oxygen membrane color. cyanosis indicate advanced supply, obstruction of hypoxemia airways by secretions, bronchospasm Monitor vital signs Encourage adequate rest and limit activities to within client tolerance.

Demonstrate improved ventilation Demonstrate adequate oxygenation of tissues by ABGs within clients normal limits absence of symptoms of respiratory distress

Monitor and graph serial ABGs and pulse oximetry.

Administer medications as indicated Increased PaCO2 signals impending respiratory failure for asthmatics.

Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. Complete blood count. Chest X-rays. Peak Expiratory Flow Rates (PEFR)

Nursing diagnosis for Asthma

Impaired gas exchange related to Altered oxygen supply obstruction of airways by secretions, bronchospasm, air-trapping Alveoli destruction Ineffective airway clearance related to obstruction from narrowed lumen and thick mucus imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements related to Dyspnea, sputum production Medication side effects; anorexia, nausea or vomiting Fatigue Ineffective breathing pattern Anxiety Deficient knowledge (treatment regimen, self-care, and discharge needs) Fear

Nursing Care Plans for Asthma Common nursing diagnosis found in Nursing Care Plans for Asthma; Impaired gas exchange, Ineffective airway clearance, imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements, Fatigue, Ineffective breathing pattern, Anxiety, Deficient knowledge (treatment regimen, self-care, and discharge needs), Fear

Sample Nursing care plans for Asthma

Patient Teaching Discharge and Home Healthcare Guidelines For Asthma To prevent asthma attacks, teach patients the triggers that can precipitate an attack. Teach the patient and family the correct use of medications, including the dosage, route, action, and side Effects. In rare instances, asthma can lead to respiratory failure (status asthmaticus) if patients are not treated immediately or are unresponsive to treatment. Explain that any Dyspnea unrelieved by medications, and accompanied by wheezing and accessory muscle use, needs prompt attention from a healthcare provider. Patient Teaching Discharge and Home Healthcare Guidelines: Teach the patient and his family to avoid known allergens and irritants.

Teach the patient about his medications, drug interactions, including proper dosages, administration instructions, and adverse effects. Teach the patient how to use a metered-dose inhaler. Explain how to use a peak flow meter to measure the degree of airway obstruction, If the patient has moderate to severe asthma. Tell him to keep a record and Explain the importance of calling the physician at once if the peak flow drops suddenly If the patient develops a fever above 100 F (37.8 C), chest pain, shortness of breath without coughing or exercising, or uncontrollable coughing. Tell the patient to notify the physician Teach the patient and his family an uncontrollable asthma attack requires immediate attention. Teach the patient diaphragmatic and effective coughing techniques. Urge him to Increase fluid intake to help loosen secretions and maintain hydration. Teach the patient and his family important of Regular medical follow-up care, when to notify healthcare professional of changes in condition, and periodic spirometry testing, chest x-rays, and sputum cultures.

http://nurse-thought.blogspot.com/2011/03/ncp-nursing-care-plan-for-asthma.html

You might also like

- Conservative Management of Placenta Accreta in A Multiparous WomanDocument10 pagesConservative Management of Placenta Accreta in A Multiparous WomanRobel Mae Lagos MontañoNo ratings yet

- NCP DepressionDocument2 pagesNCP DepressionRobel Mae Lagos MontañoNo ratings yet

- 12 Qualities of A StrongDocument6 pages12 Qualities of A StrongRobel Mae Lagos MontañoNo ratings yet

- 12 Qualities of A StrongDocument6 pages12 Qualities of A StrongRobel Mae Lagos MontañoNo ratings yet

- MSEDocument13 pagesMSERobel Mae Lagos Montaño0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Dohsa-Hou A Japanese Psycho-Rehabilitative Program For Individuals With Motor Disorders and Other DisabilitiesDocument10 pagesDohsa-Hou A Japanese Psycho-Rehabilitative Program For Individuals With Motor Disorders and Other DisabilitiesPdk MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Sotai ExercisesDocument2 pagesSotai Exerciseskokobamba100% (4)

- Nerve PainDocument1 pageNerve PainRahafNo ratings yet

- Tom's Fourth Year Guide (2011-12)Document709 pagesTom's Fourth Year Guide (2011-12)jangyNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet Squamous Cell Carcinoma Oct 2013Document10 pagesFact Sheet Squamous Cell Carcinoma Oct 2013Triven Nair HutabaratNo ratings yet

- OB-GYN+AP FinalDocument34 pagesOB-GYN+AP FinalJoanne BlancoNo ratings yet

- Abnormal PsychologyDocument4 pagesAbnormal PsychologyTania LodiNo ratings yet

- 6.myositis OssificansDocument28 pages6.myositis OssificansBhargavNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorder 1Document44 pagesEating Disorder 1Trisha Mae MarquezNo ratings yet

- Acute Diseases and Life-Threatening Conditions: Assistant Professor Kenan KaravdićDocument33 pagesAcute Diseases and Life-Threatening Conditions: Assistant Professor Kenan KaravdićGoran MaliNo ratings yet

- Adjuvant Analgesics (2015) PDFDocument177 pagesAdjuvant Analgesics (2015) PDFsatriomega100% (1)

- Types of PsychologyDocument62 pagesTypes of PsychologyParamjit SharmaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Parameters of An Extended Aeration Activated Sludge System - Water Tech Online PDFDocument9 pagesWhat Are The Parameters of An Extended Aeration Activated Sludge System - Water Tech Online PDFZoran KostićNo ratings yet

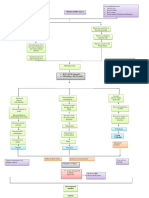

- Concept Map MarwahDocument5 pagesConcept Map MarwahAsniah Hadjiadatu AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Dr. Lazuardhi Dwipa-Simpo Lansia 97Document56 pagesDr. Lazuardhi Dwipa-Simpo Lansia 97radenayulistyaNo ratings yet

- 2 05MasteringMBBRprocessdesignforcarbonandnitrogenabatementDocument65 pages2 05MasteringMBBRprocessdesignforcarbonandnitrogenabatementYên BìnhNo ratings yet

- CBT For CandA With OCD PDFDocument16 pagesCBT For CandA With OCD PDFRoxana AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Matchstick MenDocument9 pagesMatchstick Menmichael_arnesonNo ratings yet

- Final Past Papers With Common MCQS: MedicineDocument17 pagesFinal Past Papers With Common MCQS: MedicineKasun PereraNo ratings yet

- Registered Dietitians in Primary CareDocument36 pagesRegistered Dietitians in Primary CareAlegria03No ratings yet

- AWWA Alt Disnfec Fro THM RemovalDocument264 pagesAWWA Alt Disnfec Fro THM RemovalsaishankarlNo ratings yet

- Ball Ex Chart 2014aDocument2 pagesBall Ex Chart 2014aJoao CarlosNo ratings yet

- Mechanism of Propionibacterium Acne Necrosis by Initiation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) by Porphyrin AbsorptionDocument23 pagesMechanism of Propionibacterium Acne Necrosis by Initiation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) by Porphyrin AbsorptionCaerwyn AshNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Use of The Health Belief Model For Weight ManagementDocument1 pageA Review of The Use of The Health Belief Model For Weight ManagementpatresyaNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Cardiac Risk AssessmentDocument16 pagesPreoperative Cardiac Risk Assessmentkrysmelis MateoNo ratings yet

- Mitek Anchor SurgeryDocument9 pagesMitek Anchor SurgeryHeidy IxcaraguaNo ratings yet

- A Case Study For Electrical StimulationDocument3 pagesA Case Study For Electrical StimulationFaisal QureshiNo ratings yet

- Program DevelopmentDocument16 pagesProgram Developmentapi-518559557No ratings yet

- NSTP ProjDocument11 pagesNSTP ProjLeeroi Christian Q Rubio100% (2)

- Imir Studyguide2014Document499 pagesImir Studyguide2014Sam GhaziNo ratings yet