Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Spain's Charles III - Science V Superstition 1

Uploaded by

AndrewOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Spain's Charles III - Science V Superstition 1

Uploaded by

AndrewCopyright:

Available Formats

NEW SOLIDARITY

September 19, 1980

Page 8

Spain's Charles III and The Reign of Science Over Superstition

by Robyn Quijano Part I

"Such is superstition that a whole people tremblingly reveres a piece of wood which wears the costume of a saint." This caption and drawing is part of a series of drawings, "Los Caprichos," by the 18th century painter Francisco Goya. Goya used biting irony against the superstitions and ignorance of the population.

Most Americans, including Catholics, know little of the true history of the Jesuit Order. Last June this newspaper ran a feature titled "Re-Ban the Jesuits," in which we reported the events that led to the suppression of the Jesuits by Clement XIV, The

Papal Bull, Dominus ac Redemptor, signed on July 21, 1773, required Jesuit houses sealed, schools closed, and property seized. We detailed the history of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal France, and Spain for crimes including regicide. The French Parliament expelled the Jesuits in 1762 for "exciting vengeance and homicide, protecting massacres," for being "contrary to the maxims of the Gospel, the examples of Jesus Christ, the doctrine of the Apostles . . . seditious, contrary to natural law, to divine law . . . opening the path to fanaticism and horrible carnages, troubling the society of men, creating an ever-present peril against the life of kings . . ." We demanded that the Jesuits be banned once again by the Pope for the same crimes including running international terrorist networks. This series of articles, "Why Nation Builders Must Fight the Jesuits," will present the history of the battles humanist leaders have waged against the Society of Jesus, and provide in this way the arms with which to dismantle the order once again, but this time for good. We will concentrate first on the history of Spain and Spanish America, the nations most dominated by Jesuit subversion since Jesuit Order founder Ignatius Loyola was born on Spanish soil. We ask our readers to look over our shoulders as we address the leaders of Latin America and the rest of the developing sector on the historical precedents to the current destabilizations of their nations, the Jesuit role in the current crisis, and the necessity to wage the final battle against the order that was founded as a weapon against the Catholic Church and the nation state.

Why Nation Builders Must Fight the Jesuits

On the morning of April 2, 1767, the same day, the same hour, in Spain, Spanish America, in Spanish dominions in North and South Africa, and Asia, and in all the islands of the realm, dispatches from Madrid were opened. All the officials were orderedsome say under pain of deathto immediately enter all Jesuit institutions, armed, to take possession of them, expel the Jesuits from their convents, and transport them within 24 hours as prisoners to the nearest port. They were to embark instantly, leaving their goods behind, never to return nor even to communicate in any way with anyone living within the realm of Charles III, Bourbon King of Spain.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, one of the greatest Platonic humanists of all time, would have smiled in great satisfaction. The deed was done. At last. Two hundred years overdue. What the thug and murderer Ignatius Loyola, native of Spain's Basque region began in founding the intelligence operation known as the Society of Jesus in 1540 after experimenting with every cultish perversion then known to man was finally put to an end. Cervantes had spent most of his life in political and polemical battles against Loyola and his Jesuit operatives who carried out the dirty work of the oligarchy with their advancing monopoly over education throughout Europe and the New World. The Jesuits assured the Hapsburg rulers of control over the backward and superstitious peasantry and used mob upheavals, directed with great precision, against factional opponents. Francisco Goya y Lucientes, the greatest painter of the Spanish world, did smile in satisfaction, Although Goya was a very young man at the time the Jesuits were expelled from Spain, the importance of this victory would be made immortal in one of his paintings depicting the expulsion of the Jesuits for crimes never fully explained by the deeply religious Charles III. Many of the most incisive of Goya's sketches would depict his own war against the evil represented by the Jesuits, the manipulation by the cultist clergy of the superstition and ignorance of the masses. April 2, 1767 should be seen as an anniversary of great importance for the entire Spanish speaking world. For despite the fact that it took the papacy seven years to officially disband the order, and the oligarchy maintained powers through use of the Dominicans and covert Jesuit networks that remained behind, the recapturing of the educational institutions by Charles and his network of humanist advisers allowed a crucial experiment in national development to take place. The works of both the poet Miguel de Cervantes and the painter Francisco Goya are characterized by a biting irony directed at pulling the Spanish population out of ignorance and degradation, the insanity and cultishness that characterized their daily lives. Both were part of networks that understood the Jesuits to represent the organization of this evil. Yet two hundred years separate the birth dates of these great men; Cervantes was born in 1547 and Goya, in 1746. The population of Spain had virtually stagnated in number, education and skill level during two hundred years. At the time of Cervantes' birth, a "mercantilist" faction in Spain put forward a new economic program for the nation which was bankrupt despite the silver and gold that was flowing into the country from the new world. Most of this wealth was going directly to the Genoese and other of Spain's

creditors. Creation of wealth was not even considered a factor in the national economy at the time.

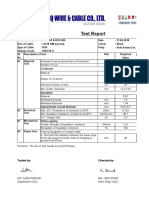

Francisco Goya painted this portrait of King Charles III as part of a commission to paint all the board members of the Bank of San Carlos, the national bank of Spain.

The mercantilists recommended the creation of national banking and customs systems, internal transport to integrate the regionalized nation, and the fostering of trade and the crafts. They saw the hidalgo class, impoverished heirs to aristocratic titles who thought it dishonorable to do any kind of work, as a great drain on the national economy and recommended that merchants and craftsmen be honored as of noble professions. National wealth could and must be generated by production and commerce. While the first Bourbon King of Spain Philip V began to impose such "mercantilist" methods to build a national economy when he took the throne after the last Hapsburg monarch in 1700, the program of the 16th century mercantilists was not implemented until the reign of Charles III (1759-1788). Charles would not have been able to create a developing national economy had he not expelled the Jesuits. The Jesuits had a capability in place to sabotage every reform he put forward. Developing nations today, faced with many of, the same problems Charles faced, would do well to study the history of his administration and the activities of the Jesuits today. Jesuit subversion of development can be most effectively combatted

by using this historical precedent, Mexico has its own historical precedent in the many expulsions of the Jesuits throughout the 19th century.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, whose famous work Don Quixote de la Mancha polemicized against the hidalgo class, the degenerate, impoverished heirs of the landed aristocracy

Political Economy and the Jesuits Why did Charles III, known as the most moral and the holiest of Catholic kings, expel the Jesuits? In a period in which the Catholic Church and the papacy were under attack, and atheism was being put forward as an "enlightened" philosophy by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Charles was a staunch defender of the faith. The monarch was deeply committed to both Christianity and science, and to a fight against the cult-like superstitions that passed as Catholicism throughout Spain. In order to bring the benefits of science into Spain, which had been totally isolated throughout the 16th and 17th centuries of Hapsburg rule when experimental science was considered heresy by the inquisition, Charles ordered a special textbook written for the Spanish universities. None of the texts from the rest of Europe could be used as none were based on the compatibility between the Catholic faith and the development of science. The new godless philosophy of the French "philosophes" was banned, but Charles ordered that the texts be written on

the basis of the philosophical systems of French philosopher Rene Descartes (1595-1650) and the German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who died the year Charles was born, 1716. Charles designed a new mandatory one year course for all Spain's universities on "the law of nature and of nations" in which student would be taught to "subject always the lights of our human reason to those of the Catholic religion, showing above all the necessary union of religion, morality, and politics." Charles III expelled the Jesuits because he was a believer in the perfectibility of man. In the nation-state dedicated to natural law, the law of man and nature, which both come from God, must triumph. Political economy, for the monarch, was the science of the perfectibility of man. This science, Charles hoped, would begin to rule the nation as the educational institutions became the guarantors of development. Charles's determination that the state must foster growth and invest in the national economy was in the tradition of his French Bourbon ancestor, Louis XIV, whose Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) advanced the mercantilist school of political economy. His economic policies created new wealth, and surplus was directed by the state back into the national economy. Educational reform was designed to make the universities become research and development centers, land reform, to assure that arable land would be cultivated instead of laying fallow in the hands of the landed aristocracy. Manufacturing centers were set up and run by the crown, trade with the American colonies was increased and wrested away from Britain which was illegally monopolizing trade with Spain's colonies. The fuero system of indian slavery was formally ended in the colonies, and a kind of commonwealth was proposed between Spain and Spanish America which would foster scientific, technological, and cultural development in the new world as well as the old. Charles defended the right of manufacturers, merchants, and artisans to be considered honorable classes, and abandoned the belief that American gold and silver could be the basis of the nation's wealth. A revolutionary idea took hold that productive labor which could be infinitely expanded through government fostered investment was the basis for the nation's wealth. This program, similar in many respects to the effort of developing sector nations today, was hampered at every point by the landed oligarchy. Development would erode the power represented by their fiefdoms. The black nobility employed the Jesuit order against King Charles and his reforms just as they had used the Society

of Jesus against the humanist city building factions since Ignatius Loyola founded the order. This time they mobilized and manipulated mobs in Madrid into rioting against the government's reforms, the first level of a "destabilization" operation designed to end in the assassination of the king. The society was well equipped to carry out this task. Regicide had been its specialty since its founding. The Sleep of Reason Goya, like Cervantes before him, never tired of creating new images to depict the backwardness and bestiality of Spanish ideology. Both masters used their art to warn against the "sleep of reason" so prevalent in Spanish society and to demonstrate the necessity of the rule of reason to the creation of a republican citizenry. When Bourbon King Phillip V took the Spanish throne from the Hapsburgs at the turn of the century, the nation was a feudalist disaster. European thought, all the important scientific and philosophical discoveries of the previous two hundred years, was outlawed by the Inquisition as heretical. The oligarchy was organized around the Mesta, a powerful grouping backed by the Jesuit-linked oligarchical faction in the Church. The Mesta saw as its privilege for centuries the right to allow sheep grazing throughout the once fertile lands of Spain at the expense of agriculture. The Mesta was so powerful that although Phillip tried to curb their power in order to encourage agricultural production in 1712, it took until 1786, two years before the death of Charles, for the government to fully abolish the Mesta's privileges of land possession. Only in 1788 were farmers given the right to enclose their lands to protect agriculture from the hoards of grazing sheep. Land reform was thus the key battle. Without some kind of dependable and growing agricultural production population growth could not be insured and plans for the expansion of manufactures and the development of urban areas would be worthless. The most powerful faction of the Spanish Church which ran the Jesuits as their intelligence operation was indistinguishable from the landed aristocracy. Both had their hands in the Mesta, both owned vast expanses of land which they refused to cultivate, and both resisted the land reform.

Charles's entire economic program depended on the triumph of agriculture, grain growing in particular, over the sheep herders. Charles and his key adviser Pedro Rodriguez, the Count of Campomanes, the architect of the agricultural reforms, believed that a prosperous peasantry would increase the wealth of the state. The government would intervene to assure the supply of food to the cities. They would distribute the land which the oligarchy refused to cultivate, and create new colonies in areas of the country with fertile land which had been totally depopulated during the reign of the Hapsburgs. Another of Charles's key economics advisers, the Count of Floridablanca, called for a nationwide fund of credit for farmers to build houses, extend irrigation, buy tools and livestock and try new crops. The real implementation of the agricultural reform would depend on the universities and the Societies of the Friends of the Country, an institution encouraged by the crown for the stated purpose of studying and popularizing new discoveries to aid in the productivity of agriculture, industry, and commerce. The societies, which opened their doors to all classes without distinction and to women in 1786, were both research and development centers and educational clubs which could ensure the most immediate upgrading of both the nation's technologies and its labor power. For every economic reform to succeed there was a great education and skill problem to solve. The societies were crucial to this effort, and the oligarchical Church was quick to recognize these organizations as a threat. But factions in the Church, particularly those centered around the Augustinian and Benedictine orders, looked to the societies as a vehicle for spreading science, faith and reason to the population. Labor Power and Superstition Under one of Goya's drawings in the Caprichos is written the following lament: "Such is superstition that a whole people tremblingly reveres a piece of wood which wears the costume of a saint!" One entire faction which had been dominant during the major part of the two centuries of Hapsburg rule promoted religious fanaticism in the population. They taught pagan cultism with a thin veneer of Catholicism as a well studied brainwashing technique to control the population and to control, by use of the "uncontrolled mob," leaders of the humanist faction. We see these same methods employed in Iran, Mexico, and throughout Latin America today. The Jesuits promote voodoo, self flagellation, and other methods

of self torture which culminate in the masochistic rites of Holy Week to maintain the population at the edge of psychosis. Populations in this state can be used by any "leader" be it Khomeini, Marat, or Danton to destroy the reign of reason. Any battle for development means a battle for labor power. Wealth is produced by man and if the population is suffering from a mass psychosis there is no way they can participate in a productive economy. This is why Charles expelled the Jesuits. But the damage of hundreds of years was hard to undo. In 1777, ten years after the Jesuits formally left Spain, and while they were still officially disbanded by the Pope, the Spanish government was forced to prohibit fanatical whipping by the mobs of penitents called "disciplinantes." The fight to allow science to reign over superstition and fanaticism was taken up early in the century by the Benedictine monk Benito Jeronimo Feijoo. Feijoo was the first religious writer within the Bourbon reform period to argue that modern science did not necessarily clash with religion, and that the sway of Aristotle in Spanish education could be broken without harm to the Catholic faith, Feijoo greatly influenced the rapid expansion of scientific study in Spain promoting the growth of observatories, botanical studies, and new schools of medicine. So strong was the movement to get the population to accept science over superstition that Charles ordered the recently discovered small pox inoculation to be broadly distributed. The Economic Boom The founding of the National Bank of Spain, the Bank of San Carlos, by Francisco Cobarrus, a close associate of Goya, in 1782, allowed for the consolidation of what can be seen as an economic miracle. In 1785, the directors of the Bank of San Carlos reported "the progress in our industry, the multiplicity of modern factories in Catalonia, the extension of those in Valencia, the growth of agriculture and the increase in demand for its products." This was the fruit of a policy of the national bank, the extension of credit into productive industry and farming which was to be implemented by the young American republic later with the creation of the national bank in Philadelphia. The building of infrastructure was probably the most important success of the reign of Charles. He was a highway builder, and constructed an important system of canals for internal transport.

The textile industry was booming. Silk looms in Valencia went from 800 in 1718 to 5000 in 1787. By the 1780s new improved spinning machines were being introduced with the aid of the Societies of the Friends of the Country, which studied the most advanced production methods being developed throughout Europe, and brought them on line with well organized speed. The greatest change in the economy was the extent to which highly productive large scale manufacturing replaced the crafts production long protected by the guilds. By 1792 the Catalan cotton industry employed 80,000 workers and exported 200 million reales worth of cottons to America. No industry in France could yet match it. Large factories were encouraged by the crown, and the textile industry itself was expanded through the government owned factories begun in 1718. The "state sector" factories produced cloth, paper, pottery, and swords. The royal cloth factory was one of the largest in the world with 40,000 spinners kept active by it. In 1777 Bilbao maintained a total crude iron production of seven thousand tons. By 1790, thanks to the credit policy of the national bank, 4000 tons were shipped to America alone. Barcelona was the most advanced urban area which boasted an advanced capitalist wool industry with factories for large scale production. The city was the high technology center of Spain where the latest local inventions and new mechanical devices were employed as well as the latest imported technologies from Europe. A seven hour work day was instituted in the factories of this city. An urban working class had been created. Spain's population had grown from 7.4 million in 1747 to 10.4 million in 1787, the year before Charles's death. In 1792 the English historian William Robertson reported that Spain's progress "must appear considerable, and is sufficient to alarm jealously, and call for the most vigorous effort of the nations now in possession of the lucrative trade which the Spaniards aim at wresting from them." Charles III had given the British aristocracy a black eye when he came to the aid of the American revolution, but the economic boom he directed in Spain and his policies for a Spanish-American commonwealth based on the same economic policy for Latin America was more than the British would tolerate.

At the death of Charles III "vigorous efforts" were used to sabotage what he had achieved. The Jesuits, many of whom had sent their treasures to England when they were disbanded by Pope Clement XIII in 1773, were back to the aid of their oligarchic masters in 1818 when they were reinstated by Pius VII.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Shape of Things To ComeDocument20 pagesThe Shape of Things To ComeAndrew100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Citroen CX Manual Series 2 PDFDocument646 pagesCitroen CX Manual Series 2 PDFFilipe Alberto Magalhaes0% (1)

- DLL CW 7Document2 pagesDLL CW 7Bea67% (3)

- IA 05 Formal MethodsDocument5 pagesIA 05 Formal MethodsAuthierlys DomingosNo ratings yet

- Proposed Multimodal Terminal: Architect Rosauro H. Jamandri, M. ArchDocument7 pagesProposed Multimodal Terminal: Architect Rosauro H. Jamandri, M. Archpepito manalotoNo ratings yet

- WAM ES Screw Conveyors Manual JECDocument43 pagesWAM ES Screw Conveyors Manual JECabbas tawbiNo ratings yet

- Tourism PlanningDocument36 pagesTourism PlanningAvegael Tonido Rotugal100% (1)

- The Northern Renaissance, The Nation State, and The Artist As CreatorDocument5 pagesThe Northern Renaissance, The Nation State, and The Artist As CreatorAndrewNo ratings yet

- Woodrow Wilson and The Democratic Party's Legacy of ShameDocument26 pagesWoodrow Wilson and The Democratic Party's Legacy of ShameAndrewNo ratings yet

- How The Malthusians Depopulated IrelandDocument12 pagesHow The Malthusians Depopulated IrelandAndrewNo ratings yet

- The Capitol Dome - A Renaissance Project For The Nation's CapitalDocument4 pagesThe Capitol Dome - A Renaissance Project For The Nation's CapitalAndrewNo ratings yet

- John Quincy Adams and PopulismDocument16 pagesJohn Quincy Adams and PopulismAndrewNo ratings yet

- Colds Are Linked To Mental StateDocument3 pagesColds Are Linked To Mental StateAndrewNo ratings yet

- John Burnip On Yordan YovkovDocument6 pagesJohn Burnip On Yordan YovkovAndrewNo ratings yet

- Don't Entrust Your Kids To Walt DisneyDocument31 pagesDon't Entrust Your Kids To Walt DisneyAndrewNo ratings yet

- How John Quincy Adams Built Our Continental RepublicDocument21 pagesHow John Quincy Adams Built Our Continental RepublicAndrewNo ratings yet

- USA Must Return To American System EconomicsDocument21 pagesUSA Must Return To American System EconomicsAndrewNo ratings yet

- Presidents Who Died While Fighting The British: Zachary TaylorDocument7 pagesPresidents Who Died While Fighting The British: Zachary TaylorAndrewNo ratings yet

- Emperor Shi Huang Ti Built For Ten Thousand GenerationsDocument3 pagesEmperor Shi Huang Ti Built For Ten Thousand GenerationsAndrewNo ratings yet

- Like William Tell, Machiavelli and Cincinnatus: WashingtonDocument6 pagesLike William Tell, Machiavelli and Cincinnatus: WashingtonAndrewNo ratings yet

- Mozart As A Great 'American' ComposerDocument5 pagesMozart As A Great 'American' ComposerAndrewNo ratings yet

- Munich's Lesson For Ronald ReaganDocument22 pagesMunich's Lesson For Ronald ReaganAndrewNo ratings yet

- America's Railroads and Dirigist Nation-BuildingDocument21 pagesAmerica's Railroads and Dirigist Nation-BuildingAndrewNo ratings yet

- William Lemke and The Bank of North DakotaDocument30 pagesWilliam Lemke and The Bank of North DakotaAndrewNo ratings yet

- Inspirational Role of Congressman John Quincy AdamsDocument5 pagesInspirational Role of Congressman John Quincy AdamsAndrewNo ratings yet

- Anniversary of Mozart's Death - The Power of Beauty and TruthDocument18 pagesAnniversary of Mozart's Death - The Power of Beauty and TruthAndrewNo ratings yet

- Mexico's Great Era of City-BuildingDocument21 pagesMexico's Great Era of City-BuildingAndrewNo ratings yet

- British Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyDocument11 pagesBritish Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyAndrewNo ratings yet

- What The Other Gulf War Did To AmericaDocument19 pagesWhat The Other Gulf War Did To AmericaAndrewNo ratings yet

- Why Project Democracy Hates Juan Domingo PeronDocument11 pagesWhy Project Democracy Hates Juan Domingo PeronAndrewNo ratings yet

- Happy 200th Birthday, Gioachino RossiniDocument2 pagesHappy 200th Birthday, Gioachino RossiniAndrewNo ratings yet

- Modern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateDocument12 pagesModern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateAndrewNo ratings yet

- Foreign Enemies Who Slandered FranklinDocument9 pagesForeign Enemies Who Slandered FranklinAndrewNo ratings yet

- Geometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleDocument12 pagesGeometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleAndrewNo ratings yet

- The Federalist Legacy: The Ratification of The ConstitutionDocument16 pagesThe Federalist Legacy: The Ratification of The ConstitutionAndrewNo ratings yet

- How Lincoln Was NominatedDocument21 pagesHow Lincoln Was NominatedAndrewNo ratings yet

- On The Importance of Learning Statistics For Psychology StudentsDocument2 pagesOn The Importance of Learning Statistics For Psychology StudentsMadison HartfieldNo ratings yet

- RV900S - IB - Series 3Document28 pagesRV900S - IB - Series 3GA LewisNo ratings yet

- Email ID: Contact No: +971562398104, +917358302902: Name: R.VishnushankarDocument6 pagesEmail ID: Contact No: +971562398104, +917358302902: Name: R.VishnushankarJêmš NavikNo ratings yet

- N6867e PXLP 3000Document7 pagesN6867e PXLP 3000talaporriNo ratings yet

- Evolution DBQDocument4 pagesEvolution DBQCharles JordanNo ratings yet

- 3.15.E.V25 Pneumatic Control Valves DN125-150-EnDocument3 pages3.15.E.V25 Pneumatic Control Valves DN125-150-EnlesonspkNo ratings yet

- S010T1Document1 pageS010T1DUCNo ratings yet

- Anth 09 3 247 07 386 Yadav V S TTDocument3 pagesAnth 09 3 247 07 386 Yadav V S TTShishir NigamNo ratings yet

- Frequency Polygons pdf3Document7 pagesFrequency Polygons pdf3Nevine El shendidyNo ratings yet

- Hayek - Planning, Science, and Freedom (1941)Document5 pagesHayek - Planning, Science, and Freedom (1941)Robert Wenzel100% (1)

- Warning: Shaded Answers Without Corresponding Solution Will Incur Deductive PointsDocument1 pageWarning: Shaded Answers Without Corresponding Solution Will Incur Deductive PointsKhiara Claudine EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Huawei Switch - Service - ConfigDocument5 pagesHuawei Switch - Service - ConfigTranHuuPhuocNo ratings yet

- DICKSON KT800/802/803/804/856: Getting StartedDocument6 pagesDICKSON KT800/802/803/804/856: Getting StartedkmpoulosNo ratings yet

- Test Report: Tested By-Checked byDocument12 pagesTest Report: Tested By-Checked byjamilNo ratings yet

- Harmony Guide DatabaseDocument7 pagesHarmony Guide DatabaseAya SakamotoNo ratings yet

- TMS320C67x Reference GuideDocument465 pagesTMS320C67x Reference Guideclenx0% (1)

- All Papers of Thermodyanmics and Heat TransferDocument19 pagesAll Papers of Thermodyanmics and Heat TransfervismayluhadiyaNo ratings yet

- Lalkitab Varshphal Chart PDFDocument6 pagesLalkitab Varshphal Chart PDFcalvinklein_22ukNo ratings yet

- Soil Liquefaction Analysis of Banasree Residential Area, Dhaka Using NovoliqDocument7 pagesSoil Liquefaction Analysis of Banasree Residential Area, Dhaka Using NovoliqPicasso DebnathNo ratings yet

- Overview of MEMDocument5 pagesOverview of MEMTudor Costin100% (1)

- Electromechani Cal System: Chapter 2: Motor Control ComponentsDocument35 pagesElectromechani Cal System: Chapter 2: Motor Control ComponentsReynalene PanaliganNo ratings yet

- Ahmed Amr P2Document8 pagesAhmed Amr P2Ahmed AmrNo ratings yet

- GARCH (1,1) Models: Ruprecht-Karls-Universit at HeidelbergDocument42 pagesGARCH (1,1) Models: Ruprecht-Karls-Universit at HeidelbergRanjan KumarNo ratings yet

- Distillation Column DesignDocument42 pagesDistillation Column DesignAakanksha Raul100% (1)