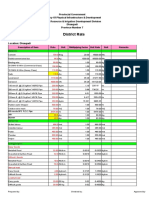

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Girls With Adhd

Uploaded by

api-313707463Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Girls With Adhd

Uploaded by

api-313707463Copyright:

Available Formats

Jenna Boyd PSIII Professional Inquiry Project, Spring 2016

jennaboydteachingportfolio.weebly.com

Girls and ADHD

What is ADHD?

ADHD stands for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. It is a neurological disorder that affects

executive function. Executive function is a set of mental skills that allow people to do things like

manage time, pay attention, switch focus, plan and organize, remember details, avoid saying or doing

the wrong thing, and apply previous experiences to current tasks. The symptoms of ADHD interfere

with, or reduce the quality of, social, academic, or occupational functioning (American Psychiatric

Association, 2013). There are three presentations of ADHD: primarily Hyperactive/Impulsive (ADHDHI), primarily Inattentive (ADHD-I), and combined (ADHD-C), which is where the criteria for both

Hyperactive/Impulsive and Inattentive are met.

How many girls have ADHD?

ADHD used to be perceived as a disorder that primarily affected boys; and it is still conceptualized as

boys disorder by most people (Littman, 2012). Boys are diagnosed with ADHD between 3 times

(community samples) and 9 times (clinic samples) as often as girls; but according to Biedermen et al.

(2012), ADHD is equally as common among women as it is among men. This means there are a

significant number of girls with ADHD who are not being diagnosed.

Why do girls get missed?

OBrien et al. (2010) found that teachers were more likely to refer a boy over a girl, even if they present

with the same symptoms. But girls do not typically present with the same symptoms as boys because

they display hyperactivity in a different way than boys do. But most girls with ADHD display little to no

hyperactivity at all because they present with the inattentive type (Groenewald et al., 2009, Guendelman

et al., 2016, Littman, 2012, & OBrien et al., 2010), making their symptoms easier to miss. These

children with ADHD-I who do not present with disruptive behaviour are less likely to be referred for

assessment, even though they may have significant difficulties. Though teachers and parents notice

difficulties in girls, they often conceptualize them as something else; usually as simply an attentional

difficulty, or emotional difficulty (Groenewald et al., 2009). The significance of girls attention

difficulties and self-control issues, is frequently underestimated.

Parents and teachers often consider low grades as one of the signs of ADHD; but girls with ADHD show

average to high average intelligence, with many even being gifted (Soffer et al., 2008). This means that

the low marks sometimes indicative of a boy with ADHD, often dont occur in girls with ADHD. These

smart girls with ADHD try very hard to hide their differences, and their good grades conceal the extreme

effort they have put forth to get them. Some of them procrastinate, then work late into the night right

before something needs to be completed. This actually helps them, because procrastinating increases

their stress level, which increases the release of noradrenalin, helping them to focus (Nadeau, 2010). For

some girls, this is the only way they can get work done.

Unfortunately for these smart girls, all of their energy goes into compensating for their cognitive

differences, leaving them drained; and successful compensation hides their ADHD from those who

could help them. These girls frequently dont get diagnosed until late adolescence or adulthood, if they

get diagnosed at all (Littman, 2012).

What does ADHD look like in girls?

Page 1 of 4

Jenna Boyd PSIII Professional Inquiry Project, Spring 2016

jennaboydteachingportfolio.weebly.com

When people think of children with ADHD, they tend to think of boys bouncing off the walls.

However, the inattentive presentation of ADHD looks quite different. Girls with ADHD-I are usually

pretty quiet and well mannered. Their difficulties are attention related. They can appear to be paying

attention, but then after instruction do not know what they are supposed to be doing. They lose things

that they need, like glasses, pencils, agendas and assignments. If they havent lost their assignments,

they may miss details in them, or do them wrong, or just forget to hand them in. It is difficult for them to

pay attention to one thing for an extended period time; or if it is something they are particularly

interested in, they might hyper-focus on it to the point where it becomes difficult to pull their attention

away from it. They start tasks, but dont finish them, because they are too difficult, or because they cant

remember what they were supposed to do, or because they take too much effort to complete to their

satisfaction.

Girls with the combined type of ADHD can show the same signs as the inattentive girls; but also show

signs of hyperactivity and impulsivity. In girls, hyperactivity can take the form of hyper-talking/chatting,

and being emotionally volatile: showing extremes of excitement, anger, happiness and sadness, at times

that seem out of place to others. Impulsiveness can take the form of interrupting, being intrusive, and

being disruptive. They can also be bossy but charismatic, and are less compliant than children without

ADHD.

How does ADHD affect girls socially?

Children with ADHD have difficulty reading social cues. When they are in a situation where they are

unsure of a persons intentions, due to an inability to read their facial expression, vocal tone, or body

language, children with ADHD tend to assume that the person has a hostile intent (Sciberras et al.,

2012). This results in reactively aggressive behavior, which is inappropriate for the intimate social

networks and social gender expectations of girls peers (Sciberras et al., 2012).

Children with ADHD are easily distracted, so even when they appear to be listening, they often are not.

They then appear uninterested in their peers, because they dont remember what friends say, or dont

respond appropriately in conversation. When trying to show interest in a conversation, the child with

ADHD may interrupt with a story about a similar experience they had, or with a story about how that

topic affects them personally; which peers see as selfish or self- centred (Giler, 2000). They appear

oblivious to others feelings, and dont recognize the impact of things that they say or do. Instead of

building rapport, AD/HD girls often alienate others. (Giler, 2000).

What happens if AHDH goes undiagnosed?

Girls with undiagnosed ADHD are frequently criticized by the adults in their life for their lack of

attention, for not listening, for failing to follow through with things, for being messy and disorganized,

for not finishing the things they start, and for forgetting important things. Accused of being lazy, selfish,

flaky, irresponsible or worse, these girls internalize that criticism, leading to feelings of shame and a

strong sense of self-blame; which can lead to permanent low self-esteem and under-functioning (Quinn

& Nadeau, 2013).

According to Sciberras et al. (2012), girls with ADHD report particularly high rates of peer

victimization, like getting bullied or excluded. They also experience high levels of peer rejection and

poor friendship stability, even as adults.

Page 2 of 4

Jenna Boyd PSIII Professional Inquiry Project, Spring 2016

jennaboydteachingportfolio.weebly.com

The DSM-V, the leading authority on diagnosing ADHD, says that adults with ADHD have a harder

time getting and keeping a job than their equally qualified peers; so they have a higher rate of

unemployment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) than adults without ADHD.

Depression frequently appears comorbid with ADHD; the most common diagnosis women have, prior to

being diagnosed with ADHD, is depression (Quinn & Nadeau, 2013). Treating the depression does not

offer much improvement if the underlying ADHD is missed.

Adult and adolescent females with undiagnosed ADHD-C are at a greater risk for antisocial, addictive,

mood, anxiety, and eating disorders (Biederman et al., 2012). They also have a high occurrence of

suicide attempts and self-harm (Hinshaw et al., 2012).

Dont kids eventually outgrow ADHD?

ADHD used to be perceived as something that boys would eventually outgrow (Guendelman et al.,

2016), because as they got older, they were less hyperactive and appeared less impulsive. However, the

symptoms of ADHD persist into adulthood for the majority of those diagnosed. For girls, symptoms

actually increase as they get older, because symptoms increase with estrogen levels (Littman, 2012). In

fact, because their symptoms went unrecognized, or were conceptualized as something else by the adults

in their lives, many people who were not diagnosed as children, are diagnosed with ADHD as adults.

Symptoms of ADHD just look different in adults. Impulsivity may manifest as interrupting people,

aggressive driving, or having addictive tendencies. Hyperactivity may manifest as constant fidgeting,

talking excessively, or getting bored quickly. Inattention may manifest as chronic lateness, constantly

misplacing phone/keys/wallet, or forgetting to pay bills or forgetting appointments. An adolescent or

adult who no longer appears hyperactive, has not necessarily outgrown the disorder.

What can we do?

More often than not, adults suspect ADHD, but decide that the child is not having enough trouble to

refer them for assessment. They wait until the child displays academic or severe social problems before

seeking out a diagnosis, but this is a mistake according to Littman (2012). Girls mature faster

neurobiologically, than boys do, so they dont need to perform as poorly as boys of the same age, in

order to be deficient enough to need help (OBrien et al., 2010).

Showing these girls that someone cares, and pointing out their academic successes, can help protect

them from some of the more significant risk factors. In fact, one of the most powerful interventions that

parents [and teachers] can offer is a consistent sense of hope (Littman, 2012). However, early

identification and intervention is key to help lessen the impact ADHD has on the lives of those who have

the disorder, their families, their peers, and their teachers.

Page 3 of 4

Jenna Boyd PSIII Professional Inquiry Project, Spring 2016

jennaboydteachingportfolio.weebly.com

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. doi:

10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01

Biederman, J., Petty, C. R., OConnor, K. B., Hyder, L. L., Faraone, S. V. (2012). Predictors of

persistence in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from an 11-year

controlled follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125, 147156.

doi:10.1111/j.16000447.2011.01797.x

Giler, J. Z., (2000). Are Girls with AD/HD Socially Adept? Retrieved from

http://www.chadd.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rDK3seKyzkc%3D

Groenewald, C., Emond, A., Sayal, K. (2009). Recognition and referral of girls with Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder: case vignette study. Child: care, health and development, 35, 6, 767

772. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00984.x

Guendelman, M. D., Owens, E. B., Galn, C., Gard, A., Hinshaw, S. P. (2016). Early-adult correlates of

maltreatment in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Increased risk for internalizing

symptoms and suicidality. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 114.

doi:10.1017/s0954579414001485

Hinshaw, S. P., Owens, E. B., Zalecki, C., Huggins, S. P., Montenegro-Nevado, A. J., Schrodek, E., et al.

(2012). Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early

adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 10411051. doi:10.1037/a0029451

Littman, E. (2012). The Secret Lives of Girls With ADHD. Attention, 1520. Retrieved from

http://drellenlittman.com/secret_life_of_girls_with_adhd.pdf

Nadeau, K. (2010). Raising Girls with ADHD. Attention, 1012. Retrieved from

http://www.chadd.org/AttentionPDFs/ATTN_8_10_ATE_Raising_Girls_Nadeau.pdf

OBrien, J. W., Dowell, L. R., Mostofsky, S. H., Denckla, M. B., Mahone, E. M. (2010).

Neuropsychological Profile of Executive Function in Girls with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 25, 656670. doi:10.1093/arclin/acq050

Sciberras, E., Ohan, J., Anderson, V. (2012). Bullying and Peer Victimisation in Adolescent Girls with

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Child Psychology Hum Dev, 43, 254270.

doi:10.1007/s10578-011-0264-z

Soffer, S. L., Mautone, J. A., & Power, T. J. (2008). Understanding girls with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): applying research to clinical practice. The International

Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 4(1), 14+. Retrieved from

http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE

%7CA214102573&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=leth89164&it=r&p=HRCA&sw=w&asid=85b5710

6b0a4cfa9bd01d4dfed801d29

Quinn, P. O., Nadeau, K. G. (2013). Understanding Girls with AD/HD Part I: Improving the

Identification of Girls with AD/HD. National Center for Gender Issues and AD/HD, Monograph

Series. Retrieved from https://roots2learning.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/girls-with-adhd.pdf

Page 4 of 4

You might also like

- Girls With Adhd FinalDocument11 pagesGirls With Adhd Finalapi-510184538No ratings yet

- AdhdDocument24 pagesAdhdramg75No ratings yet

- Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument9 pagesAttention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorderapi-608455943No ratings yet

- All About AdhdDocument27 pagesAll About AdhdVeio Macieira100% (1)

- The Effect ADHD Has On Marriage: Fostering A Strong RelationshipFrom EverandThe Effect ADHD Has On Marriage: Fostering A Strong RelationshipRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- ADHD: Diagnoses, Difficulties, and Advice for Hyperactive Children and AdultsFrom EverandADHD: Diagnoses, Difficulties, and Advice for Hyperactive Children and AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ADHD RAISING AN EXPLOSIVE CHILD: Methods for Bringing Order to Even the Most Disorganized Child That Does Not Involve Yelling (2022 Guide for Beginners)From EverandADHD RAISING AN EXPLOSIVE CHILD: Methods for Bringing Order to Even the Most Disorganized Child That Does Not Involve Yelling (2022 Guide for Beginners)No ratings yet

- ADHD: A Comprehensive Guide to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Both Adults and Children, Parenting ADHD, and ADHD Treatment OptionsFrom EverandADHD: A Comprehensive Guide to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Both Adults and Children, Parenting ADHD, and ADHD Treatment OptionsNo ratings yet

- ADHD: Symptoms and Solutions for Men and Women with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderFrom EverandADHD: Symptoms and Solutions for Men and Women with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderNo ratings yet

- Adult ADHD Treatment: The Pros And Cons - How To Treat ADHD EffectivelyFrom EverandAdult ADHD Treatment: The Pros And Cons - How To Treat ADHD EffectivelyNo ratings yet

- Understanding ADHD: What causes ADHD and how to deal with itFrom EverandUnderstanding ADHD: What causes ADHD and how to deal with itRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ADHD Guide Attention Deficit Disorder: Coping with Mental Disorder such as ADHD in Children and Adults, Promoting Adhd Parenting: Helping with Hyperactivity and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helping with Hyperactivity and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)From EverandADHD Guide Attention Deficit Disorder: Coping with Mental Disorder such as ADHD in Children and Adults, Promoting Adhd Parenting: Helping with Hyperactivity and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helping with Hyperactivity and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- ADHD Not Just Naughty: One mum's roadmap through the early challenges of ADHDFrom EverandADHD Not Just Naughty: One mum's roadmap through the early challenges of ADHDNo ratings yet

- ADHD: Traumas, Symptoms, Medication, Treatments, and TipsFrom EverandADHD: Traumas, Symptoms, Medication, Treatments, and TipsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Messy Purse Girls - Women and ADHDDocument5 pagesMessy Purse Girls - Women and ADHDgramarina100% (7)

- Misdiagnosis: ADHD or Depression?Document24 pagesMisdiagnosis: ADHD or Depression?Judie GadeNo ratings yet

- ADDventurous Women ADHD Check List 2011Document6 pagesADDventurous Women ADHD Check List 2011Judie GadeNo ratings yet

- Feature SOF Adhd: Module Output No. 1Document5 pagesFeature SOF Adhd: Module Output No. 1Jin VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Women and ADHDDocument5 pagesWomen and ADHDMaya Echegaray75% (4)

- 7 Myths About ADHD - DebunkedDocument1 page7 Myths About ADHD - DebunkedDalila VicenteNo ratings yet

- Funny Wiring: All About AutismDocument352 pagesFunny Wiring: All About AutismGail Buckley100% (4)

- Adhd - Asrs .ScreenDocument4 pagesAdhd - Asrs .ScreenKenth GenobisNo ratings yet

- Optimal Management of The Older Adult With AdhdDocument9 pagesOptimal Management of The Older Adult With Adhdkaram aliNo ratings yet

- Discipline Strategies For Adhd ChildrenDocument8 pagesDiscipline Strategies For Adhd ChildrenAngeles Rb100% (1)

- NICE. Guideline AdhdDocument664 pagesNICE. Guideline Adhddiana noliNo ratings yet

- Manage Adult ADHD with Expert TipsDocument8 pagesManage Adult ADHD with Expert TipsAndrii DutkoNo ratings yet

- ADHD Treatment: Subtypes and ComorbidityDocument22 pagesADHD Treatment: Subtypes and ComorbiditydionysiaNo ratings yet

- The Adult ADHD Handbook for Patients, Family & FriendsFrom EverandThe Adult ADHD Handbook for Patients, Family & FriendsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- RSD: What Is Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria and How Can It Be TreatedDocument3 pagesRSD: What Is Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria and How Can It Be TreatedDomingo Ignacio100% (3)

- Adhd Add Adult TestDocument1 pageAdhd Add Adult Testlogan50% (2)

- ADHD Pathway GuideDocument28 pagesADHD Pathway GuideFreditya Mahendra Putra100% (1)

- ADHD School ToolkitDocument24 pagesADHD School ToolkitClaudia Ychm100% (1)

- Adult ADHD Symptom Checklist-Observer Version #6183Document1 pageAdult ADHD Symptom Checklist-Observer Version #6183ChrisNo ratings yet

- Oppositional Defiant DisorderDocument3 pagesOppositional Defiant DisorderMANIOU KONSTANTINANo ratings yet

- AdhdDocument72 pagesAdhdalotfya100% (1)

- Adhd A Guide For Parents: Understanding Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument28 pagesAdhd A Guide For Parents: Understanding Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderMary Carmen Rodriguez100% (1)

- SNAP-IV-C Rating Scale # 6160Document1 pageSNAP-IV-C Rating Scale # 6160ChrisNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate ADHD Toolkit 1Document15 pagesThe Ultimate ADHD Toolkit 1Kirtana Jayagandan100% (6)

- Adult ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment GuideDocument19 pagesAdult ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment GuideJavier Cotobal100% (1)

- 14 Tips Parenting ADHD TeensDocument1 page14 Tips Parenting ADHD TeensCornelia AdeolaNo ratings yet

- Self-Care For Kids Es Mylemarks LLCDocument2 pagesSelf-Care For Kids Es Mylemarks LLCNYASIA GREELYNo ratings yet

- ADHD Through The Life CycleDocument34 pagesADHD Through The Life Cyclegamesh waran ganta100% (4)

- ADHD Symptoms in Healthy Adults Are Associated With Stressful Life Events and Negative Memory BiasDocument10 pagesADHD Symptoms in Healthy Adults Are Associated With Stressful Life Events and Negative Memory BiasRaúl Añari100% (1)

- ADHD Coaching ResourcesDocument2 pagesADHD Coaching Resourceshamid100% (4)

- Emotional Intelligence As An Evolutive Factor On Adult With ADHDDocument9 pagesEmotional Intelligence As An Evolutive Factor On Adult With ADHDDoctora Rosa Vera GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Adult ADHD Screening Checklist GuideDocument3 pagesAdult ADHD Screening Checklist GuideFAKESIGNUPACCOUNTNo ratings yet

- ADHD Parent Skills Training ManualDocument85 pagesADHD Parent Skills Training ManualLalita Marathe100% (1)

- ADHD Screening Test PDFDocument20 pagesADHD Screening Test PDFdcowan94% (17)

- Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale - Self Report (Wfirs-S)Document2 pagesWeiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale - Self Report (Wfirs-S)Mariana LópezNo ratings yet

- School ODD Strategies PDFDocument2 pagesSchool ODD Strategies PDFRosangela Lopez CruzNo ratings yet

- ADHD in AdultsDocument7 pagesADHD in AdultsaskdoctorjohnNo ratings yet

- Download+Resource List 0809Document7 pagesDownload+Resource List 0809JLOberli100% (1)

- Adult Adhd 2Document5 pagesAdult Adhd 2Pankti buchNo ratings yet

- PARENT - Combined ADHD and DBD Workbook PDFDocument35 pagesPARENT - Combined ADHD and DBD Workbook PDFPrachi_Pokharkar100% (1)

- 7 Crucial Tips For Parents and Teachers of Children With AdhdDocument67 pages7 Crucial Tips For Parents and Teachers of Children With AdhdmiccassNo ratings yet

- Executive Functions and ADHD in Adults EvidenceDocument13 pagesExecutive Functions and ADHD in Adults Evidencedianisvillarreal100% (1)

- Jenna Boyd Small Animals Project Grade 2 Science Topic E: Small Crawling and Flying AnimalsDocument3 pagesJenna Boyd Small Animals Project Grade 2 Science Topic E: Small Crawling and Flying Animalsapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Jennas TimetableDocument1 pageJennas Timetableapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Intern Professional Growth PlanDocument3 pagesIntern Professional Growth Planapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Weather Unit TestDocument6 pagesWeather Unit Testapi-313707463100% (1)

- Battle For Arctic WorksheetDocument2 pagesBattle For Arctic Worksheetapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Saskatoon Lesson 2Document2 pagesSaskatoon Lesson 2api-313707463No ratings yet

- Plasticine TreeDocument5 pagesPlasticine Treeapi-313707463No ratings yet

- MathunitplanDocument29 pagesMathunitplanapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Im-5 Declaration English and FrenchDocument2 pagesIm-5 Declaration English and Frenchapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Long Range PlanDocument3 pagesLong Range Planapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Science Unit Plan: Jenna BoydDocument24 pagesScience Unit Plan: Jenna Boydapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Making TenDocument3 pagesMaking Tenapi-313707463No ratings yet

- Instructional StrategiesDocument48 pagesInstructional Strategiesapi-31370746350% (2)

- 1 The Fifth CommandmentDocument10 pages1 The Fifth CommandmentSoleil MiroNo ratings yet

- HBSE-Mock ExamDocument3 pagesHBSE-Mock ExamAnneNo ratings yet

- Heal Yourself in Ten Minutes AJDocument9 pagesHeal Yourself in Ten Minutes AJJason Mangrum100% (1)

- Small Gas Turbines 4 LubricationDocument19 pagesSmall Gas Turbines 4 LubricationValBMSNo ratings yet

- Lines WorksheetDocument3 pagesLines WorksheetJuzef StaljinNo ratings yet

- Adolescent and Sexual HealthDocument36 pagesAdolescent and Sexual Healthqwerty123No ratings yet

- Peugeot 206 Fuse Diagram PDFDocument6 pagesPeugeot 206 Fuse Diagram PDFDedi dwi susanto100% (2)

- Rise School of Accountancy Test 08Document5 pagesRise School of Accountancy Test 08iamneonkingNo ratings yet

- Reading 1Document2 pagesReading 1Marcelo BorsiniNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Characterization of Galactomannan From Sugar PalmDocument4 pagesIsolation and Characterization of Galactomannan From Sugar PalmRafaél Berroya Navárro100% (1)

- Ficha Tecnica StyrofoamDocument2 pagesFicha Tecnica StyrofoamAceroMart - Tu Mejor Opcion en AceroNo ratings yet

- Solucionario. Advanced Level.Document68 pagesSolucionario. Advanced Level.Christian Delgado RamosNo ratings yet

- Khatr Khola ISP District RatesDocument56 pagesKhatr Khola ISP District RatesCivil EngineeringNo ratings yet

- Environmental Product Declaration: PU EuropeDocument6 pagesEnvironmental Product Declaration: PU EuropeIngeniero Mac DonnellNo ratings yet

- Amaryllidaceae Family Guide with Endemic Philippine SpeciesDocument28 pagesAmaryllidaceae Family Guide with Endemic Philippine SpeciesMa-anJaneDiamos100% (1)

- CASR Part 830 Amdt. 2 - Notification & Reporting of Aircraft Accidents, Incidents, or Overdue Acft & Investigation OCRDocument17 pagesCASR Part 830 Amdt. 2 - Notification & Reporting of Aircraft Accidents, Incidents, or Overdue Acft & Investigation OCRHarry NuryantoNo ratings yet

- Assessing Inclusive Ed-PhilDocument18 pagesAssessing Inclusive Ed-PhilElla MaglunobNo ratings yet

- Delta C200 Series AC Drives PDFDocument5 pagesDelta C200 Series AC Drives PDFspNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Integrative Homeopathy - Bob LeckridgeDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Integrative Homeopathy - Bob LeckridgeBob LeckridgeNo ratings yet

- Otology Fellowships 2019Document5 pagesOtology Fellowships 2019Sandra SandrinaNo ratings yet

- App 17 Venmyn Rand Summary PDFDocument43 pagesApp 17 Venmyn Rand Summary PDF2fercepolNo ratings yet

- Introduction of MaintenanceDocument35 pagesIntroduction of Maintenanceekhwan82100% (1)

- 21 - Effective Pages: Beechcraft CorporationDocument166 pages21 - Effective Pages: Beechcraft CorporationCristian PugaNo ratings yet

- IC 33 Question PaperDocument12 pagesIC 33 Question PaperSushil MehraNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 P.EDocument16 pagesGrade 9 P.EBrige SimeonNo ratings yet

- Chambal Cable Stayed Bridge Connecting ShoresDocument6 pagesChambal Cable Stayed Bridge Connecting Shoresafzal taiNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Air FilterDocument5 pagesProject Report On Air FilterEIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNo ratings yet

- 3.SAFA AOCS 4th Ed Ce 2-66 1994Document6 pages3.SAFA AOCS 4th Ed Ce 2-66 1994Rofiyanti WibowoNo ratings yet

- Bespoke Fabrication Systems for Unique Site SolutionsDocument13 pagesBespoke Fabrication Systems for Unique Site Solutionswish uNo ratings yet

- Amputation and diabetic foot questionsDocument69 pagesAmputation and diabetic foot questionspikacu196100% (1)