Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Final Program Eval Paper

Uploaded by

api-280536751Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Final Program Eval Paper

Uploaded by

api-280536751Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

Motivating Students to Volunteer: Revealing Reasons to Get Involved

Ryan Bishop

Sara Hogue

Danny Ledezma

Leah Sadoian

Azusa Pacific University

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

Abstract

This research study sought to answer the question What are the motivators and benefits that

influence undergraduate college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a private

faith-based institution? The Center for Student Action (CSA) at Azusa Pacific University (APU)

was used as a case study for motivation to volunteer. Participants from a small, private, faithbased institution (APU) completed an online survey which listed various statements prompting

motivation to volunteer. Primary motivators of the participants included opportunities to engage

with diverse communities, feeling close to God, feeling a sense of purpose during

volunteerism, and past experience volunteering. This research concluded that location,

opportunity for diversity, and spiritual motivation were key reasons why participants chose to

volunteer with the CSA. These motivators aligned with the CSAs learning outcomes for

students, strengthening the credibility of the center on campus. The CSA was also evaluated

according to CAS Standards for Service-Learning Programs, with suggestions for improvement

relating to this studys findings.

Keywords: volunteer, motivation, undergraduate, student, involvement, faith

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

Volunteerism, or the decision to volunteer ones time or talents for the charitable,

educational, or other worthwhile activities in the community, is becoming a landmark trait in

individuals. From young children learning the importance of helping others, to the elderly

finding purpose in giving back to communities that supported and raised them, the act of

volunteering continues to be an important aspect of humankind.

Emerging adults, specifically college students, are also realizing the importance of

volunteerism. There is a variety of significant development that occurs during the college years,

and as students realize the world is larger than just themselves, a need to give back and volunteer

begins to grow. Many colleges and universities offer service-learning opportunities for students,

creating space to engage with a variety of communities while practicing healthy volunteerism.

This current study focused on the main factors that influence undergraduate college students

decisions to participate in volunteer service. Understanding the motivations behind volunteer

service among college students will help campuses create more opportunities and volunteer

experiences that will benefit both the students who volunteer, and those who receive their

service.

Literature Review

This current study focuses on learning the main factors that influence undergraduate

college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a private, faith-based institution.

This research is narrowed down to specific type of institution and student population, so it is

important to review other relevant literature around the topic of motivation to engage in

volunteer service. Three main categories of motivation are discussed here. First, the impact on

the individual who volunteers, second, the significant impact on the university and surrounding

community, and finally, the large emphasis on volunteering as a way for individuals to prepare

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

for their future. These three main categories of motivations lay the groundwork for why students

choose to volunteer, and provide a framework to compare and contrast the reasons why

undergraduate students participate in volunteer service at a private, faith-based institution.

Impact on the Individual

Although the focus of volunteering is on the person being helped, research shows that

becoming engaged in volunteering can impact the volunteer him/herself while in college, and

also well into adulthood. One longitudinal study that began in 1990 looked at the lasting impact

on the well-being of students who volunteered and are now adults in their mid-thirties (Bowman,

Brandenberger, Lapsley, Hill, & Quaranto, 2010). The results of the study showed that graduates

who engaged in volunteering and also taking at least one service learning course reported a

positive relation on well-being 13 years later (Bowman et al., 2010). Specifically the types of

well-being reported were personal growth, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and life

satisfaction (Bowman et al., 2010). This research is important because it shows that community

involvement while in college is a good predictor of well-being long after college is over. While

volunteering has an impact on ones well-being well into adulthood, a study done in 2010

explored the connection between Eriksons generativity or concern for others to take action and

ones faith (religiosity or spirituality) (Brady, & Hapenny, 2010). 94 undergraduates from a

religiously affiliated college were surveyed to measure their generative behavior using the

Generative Behavior Checklist. Students also took a religious assessment to measure their

religiosity (Brady, & Hapenny, 2010). Results showed three things. First, there was a correlation

between generative concern and spiritual identity. Second, there is partial support for a positive

correlation between religiosity and generative concern. Finally, results showed a positive

correlation between a high level of religious involvement and identification with the millennial

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

generation (Brady, & Hapenny, 2010). The last result was unexpected by the researchers but

showed that millennials are a group of young adults that care deeply about their faith, engage in

its customs and show a growing awareness of the needs of others (Brady, & Hapenny, 2010).

With the millennial generation entering or already in college, faith based institutions such as

Azusa Pacific University will start to see an influx in a desire to help others and students seeking

to engage in the community. This is an opportune time to build up programming for volunteering

so students will be set up for a flourishing adulthood, as the research suggests.

As volunteering encourages internal rewards for college students, colleges also provide a

way for underrepresented students, such as Latino/a students, to experience volunteering and

community engagement (Fajardo, Lott, & Contreras, 2014). Previous research shows that college

experiences impact volunteerism for Latino/a students because it seems to shape their behaviors

into adulthood (Fajardo et al., 2014). One study done in 2014 showed that Latino/as that rated

themselves with high leadership ability were more likely to volunteer because they saw it as a

vehicle to social change and were more likely to have a socially responsible leadership

disposition (Fajardo et al., 2014). Latino/a students are also more likely to volunteer if they

regularly attended a religious service. (Fajardo et al., 2014). As more research is done to expand

these findings about how educational experiences impact civil engagements especially for

Latina/o students, the influence of these experiences will have a positive impact on the lives of

Latina/o students as adults and on the broader community (Fajardo et al., 2014). For

administrators in the student affairs field, it is important to also remember the needs of all

students and develop programming that will positively impact them as well.

Although there are many positive impacts for the individual, research also exists that does

not support the benefits of volunteering in college. Sometimes, college students struggle to make

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

sense of their volunteering and have a difficulty coming to terms with the social problems that

they encounter in their volunteering (Holdsworth & Quinn, 2011). This can cause a negative

experience and cause students to avoid volunteering in the future. Volunteering can also cause

perpetuation of inequalities because students see themselves as doing good and not taking the

experience as potential for transformation (Holdsworth & Quinn, 2011). To avoid a negative

impact, institutions must allow students to deconstruct their experiences with a collective

community (Holdsworth & Quinn, 2011). It is also up to the institution to not take volunteering

as a win/win situation but communicate with students on what to expect (Holdsworth &

Quinn, 2011). Colleges also must see volunteering as a space where students can step outside of

their comfort zones and explore a world they would otherwise never know (Holdsworth &

Quinn, 2011). Programming needs to be in place for students to explore what they are doing but

also have time to deconstruct their experiences and create meaning on what they saw and

learned. As students explore a world that is new to them, they start to learn about social justice

and the impact that has on their faith and cognitive development.

A study done in 2013 explores the relationship between faith and social justice. Results

showed that there is a strong relation between social justice activities and faith maturity meaning

that college students engagement in social issues reflects their faith maturity and their attitudes

towards social justice (Kozlowski et al., 2013). Faith based institutions benefit in focusing their

programing towards social justice attitudes, faith maturity and civic engagement because there is

a call for civically engaged citizens, the understanding of the needs of others, and the mentality

to come always and serve (Kozlowski et al., 2013). If students are given the opportunity to

deconstruct what they are learning, while volunteering and also being exposed to social justice,

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

the impact on the individual creates an engaged citizen who seeks to understand and help others

well into their adult life.

Volunteer setting and students own personal beliefs are two ways students are set up for

success in volunteering. A study done in 2014 asked students what motivates them to volunteer.

The results showed that one fifth of the 406 volunteers surveyed volunteered with a faith based

organization (Moore, Warta, & Erichsen, 2014). These results show that faith based institutions

are in a prime arena to engage students to volunteer and utilize their values. The types of students

who volunteer are typically introverted and also female, but that is not to say males and

extraverts do not volunteer (Trudeau & Devlin, 1996). Students also recognize and appreciate

community service and see it as a way to give back to the community (Trudeau & Devlin, 1996).

If students are given the opportunity to seek social justice, step out of their comfort zone and

given the space to explore what they learned while they are college; colleges will be graduating

well rounded students who will go into the world with a service-oriented mindset. The impact on

the individual spreads also to the university and surrounding community, who benefit from

student volunteerism as well.

Impact on the University and the Community

Volunteer service by undergraduate students has great impact on both the university as

well as the community it is serving. One of the most vital aspects to college students

volunteering can be found in Sullivans (2013) study that emphasized campus culture of

volunteering (Sullivan, Ludden & Singleton, 2013). Sullivan created a quantitative study which

looked directly at the Universitys mission statement and what influence it had over the

volunteering of a student body (Sullivan, Ludden & Singleton, 2013). Sullivan found that a when

volunteering is being promoted by school officials, the student body is also encouraged to

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

volunteer (Sullivan, Ludden & Singleton, 2013). It is always important to remember the

institutions effect on the student body volunteering or not. For some private faith based

institutions, volunteering is required so it is important for an institutions mission statement and

culture to cultivate a sense of community service and community pride.

A college or university is able to promote and cultivate community service work by

knowing what and where its students can get involved. A 2014 study done on more than 90,000

students from 1,600 postsecondary institutions tracked the popularity of different forms of

community or volunteer service and who was involved with them. Of the over 90,000 students

surveyed nearly 50% of them volunteered with community service and 15% reported that their

college program required community service (Griffith & Thomas, 2014). An interesting finding

showed that students who were required to have community service performed activities

involving more direct assistance to the needy, whereas those who were not required to perform

community service performed activities in connection to larger, more formal institutions (Griffith

& Thomas, 2014). Where and why are very important motivational factors in how community

service and volunteer work affects the institution. At the private faith based institution, Azusa

Pacific University (APU), there is an example of what impact volunteering and community

service has had on an institution. The Center for Student Action (CSA) is a fully funded office

with the purpose to have students be a part of the local and global community. CSA learning

outcomes reflect this overarching purpose. (Center for Student Action, n.d.). The offices

learning outcomes are based on the four cornerstone of the University: Christ, Community,

Scholarship, and Service. It is here at APU and the Center for Student Action that there is an

impact of both the university and the local community. The learning outcomes of the office itself

help keep in focus all of the work that comes out of the office on the good of the student, the

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

university, and just as importantly the local and global community as a whole (Center for Student

Action, n.d.). For a more in depth look at the partnership between a university and the

community around them, Anyon (2007) studied the potentiality of community and university

partnership by focusing on bringing growth and development to both the community and its

residents (Anyon & Fernandez, 2007). Anyon and Fernandez (2007) discuss The John W.

Gardner Center for Youth and its partnership with Stanford University. This partnership is

highlighted because of the adversities it overcame to become an example for other colleges

(Anyon & Fernandez, 2007). In fact, the center now is working to build its own endowment

because of the one-time gifts it was able to secure through the university president and dean

(Anyon & Fernandez, 2007). As a community flourishes, so also does relationships between

students, staff, and the university as a whole.

Dr. John August Hoffman (2012) discovered this in his study that explored the

relationship between community service and volunteer work with students own personal feeling

of connectedness and belonging (Hoffman, 2012). Results found a strong connection between

those who engaged in community service work activities and the perceptions of the importance

of community service work as well as positive feelings of connectedness to the community

(Hoffman, 2012). The sense of reward and purpose that the students felt was belonging and

connectedness to the local community in which they served. This shows the motivation not only

for students who get involved but also a motivation for colleges and universities because of the

connection to community that does indeed take place.

Although it is very important for universities to support student engagement and create

the culture for volunteerism, requiring volunteer service may not be effective. After surveying

over 400 students, a study at the University of Oklahoma found that community connectedness

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

10

was the main factor engagement in community service and some factors, such as cost to

providing service and awareness of community needs, were lowest on the scale (Hellman,

Hoppes, & Ellison, 2006). Although this sample of students used by the study were only healthrelated professionals, it still provides a foundation that shows a main motivating factor to

volunteer and engage in community service (Hellman, Hoppes & Ellison, 2006). Community

service work and volunteering at a private faith based institution is something that impacts the

life of the university and the community it is involved in deeply. The research shows that the

motivation of connectedness and belonging being a main factor in volunteering. These aspects,

along with others, help provide preparation for an individuals future. Being prepared for the

future is another major motivation for why students choose to volunteer.

Preparing for the Future

Volunteer service has a great impact on the life of a young adult. During their

undergraduate career, young adults look for opportunities to get involved. Even if volunteer

service is not required, students are looking for meaningful experience to impact their view on

the world. Beehr, LeGro, Porter, Bowling, and Swader (2014) examined required and nonrequired volunteering. Students who are required to volunteer tend to look for rewards, while

student who volunteer on their own accord, will look for feelings of satisfaction and pleasure

(Beehr et al., 2010). Many students are looking to get involved in order to help their community.

A study identified five subscales to understand what undergraduate students are looking for from

their university; civic engagement being the most important factor for undergraduate students to

have from their university (Droege & Ferrari, 2012). Motivating students to volunteer and

engage in their community is important. In her article, Weston (2013) focuses on the importance

of volunteering before students enter college. If students are taught the importance of

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

11

volunteering and civic engagement, their undergraduate experience will be filled with civic

engagement. Students who express a desire to volunteer at the beginning of college are more

likely to become engaged showing that students desire to volunteer in college is not based solely

on college experiences (Rockenback, Hudson, & Tuchmayer, 2014).

It is important to learn which factors are associated with civic engagement in younger

generations because these factors may influence how young adults shape and contribute to the

betterment of society. Droege and Ferrari (2012) state that civic engagement, civic leadership,

community involvement, volunteering, giving to charity, and involvement with alma mater and

can positively impact communities by addressing and assisting with local needs. Engagement

can foster a sense of civic responsibility, creating positive attitudes toward involvement (Droege

& Ferrai, 2012). Community involvement may lead to a greater sense of understanding by

promoting a sense of identity, community, and purpose. As students become actively engaged in

their community, they understand national, international, and local issues that are related to

systemic injustices (Litttenberg-Tobias, 2014). Participating in civic engagement plays an

important role in the development of social justice attitudes (Littenberg-Tobias, 2014). It is

important to note that different types of service will have different effects on social justice

attitudes. Littenberg-Tobias (2014) found that group-based programs are more strongly related to

social justice attitudes than individual or one-time volunteer programs. This suggests that peers

may be an important factor in how students social justice attitudes change.

Civic engagement has begun to impact the future of undergraduate students. Students

civic involvement in college is positively correlated with attitudes supportive of civic

engagement within each of students four year in college (OLeary, 2014). Weston (2014)

explains that high school students feel more pressured to do volunteer service during their times

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

12

off or summers in order to get accepted to a university. OLeary (2014) conducted a study that

provided valuable insight about which type of civic engagement involvement was more common

and during what point in the students college experience. Overall, it displayed that those

students regularly involved in civic engagement activities in college display stronger

commitments to civic engagement ideals. Students feel a need to become employable by doing a

type of civic engagement (Holdsworth & Brewis, 2014). A degree from a university is not

enough to get a job. Undergraduate students find themselves doing volunteer work in order to

gain experience in their fields (Holdsworth & Brewis, 2014). While students have become aware

of this new trend, it has not had a positive impact in encouraging students to get involved.

Employability has become a negative factor to promoting civic engagement because students are

resenting being told what to do and feel they are being controlled (Holdsworth & Brewis, 2014).

Students success amounts to more than graduation rate, grades, degree achieved, and job

placement; it includes outcomes that reflect the capacity to make meaningful contribution to the

society in which they live (Rockenback, Hudson, & Tuchmayer, 2014). Undergraduate students

must understand how the college experience promotes values and behaviors toward citizenship,

life meaning, and purpose.

This current study focuses on learning the main factors that influence undergraduate

college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a private, faith-based institution.

Impact on the individual, university and community, and preparation for the future are three

major categories of why students choose to volunteer. These three categories also reflect

outcomes students seek in volunteering and with this in mind, we can move forward in our

research on why undergraduate students participate in volunteer service at a private, faith-based

institution.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

13

Method

Research Question

This study sought to answer the following question. What are the motivators and benefits

that influence undergraduate college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a

private faith-based institution? Our goal is to build a foundation of understanding for the

motivating factors behind why students engage in community service, building off the variables

identified in existing literature, specifically the impact on the individual, impact on

university/community, and preparation for the future. The purpose of this study is to identify the

factors that motivate college students to volunteer, in order to benefit the Center for Student

Action (CSA) at Azusa Pacific University. The Center for Student Action is an office for

undergraduate students that provide opportunities for students to volunteer. Azusa Pacific

University is a small, private, Christian university located in Southern California. We developed

a survey to help asses why students engage in volunteerism based off of existing literature, CAS

Standards, and students previous involvement with the Center for Student Action. We designed

this survey to ultimately help answer the question of why students chose to volunteer.

Participants

Students who are involved with the Center for Student Action are spread throughout

campus, so in order to reach this vast population; we chose to build an online survey through

Google Forms. This survey was then distributed to the students through the directors in the

Center for Student Action via email. The surveys went to three teams overseen by the directors at

the Center for Student Action: Action Teams, Local Ministries, and Mexico Outreach. This was

our target population and we chose to distribute through the directors to increase the likelihood

of students responding since they would be seeing a name they recognized instead of one of ours.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

14

An incentive was also provided, with students being entered to win one of two gift cards if they

completed the survey. We received 217 completed surveys of the approximate 1,800 sent out.

This form of sampling is considered convenience sampling because the survey was sent out to all

of the students involved but we are only counting the ones returned within the first week of the

survey being sent out (Schuh, 2009 pg. 85). The sample consisted of undergraduate college

students between the ages of 18 23. There were 157 Female participants and 59 Male

participants and 1 who chose not to answer this question. The racial/ethnic makeup of the sample

was 133 White, 29 Hispanic/Latino/a, 30 Asian, 4 Black/African American, 1 American Indian or

Alaskan, 14 Mixed Race, 2 Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and 3 chose not to

answer. 212 identified as Christian, 2 as Catholic, 1 as Unaffiliated and 2 chose not to answer.

Because these students have past volunteer experience with CSA, it provides a clearer picture of

what motivates students to volunteer. Strengths of this survey include reaching students via email

rather than a single event, incentives offered for participants, and the timing of the survey. The

Mexico Outreach Team (one of three main groups of participants for this survey) had recently

returned from their volunteer service trip when the survey was sent out. Because students just

returned from serving, their motivation to fill out this survey increased since they had recently

volunteered. Some weaknesses with this survey is Azusa Pacific Universitys student population,

which is predominantly White. This caused the number who responded to be predominantly

white, so the responses of minorities are not well represented. Another weakness is because of

deadlines with this project, we only collected the surveys that were returned in the first week

instead of allowing more time for students to turn in the survey. This is also the only time a

survey like this has been sent out so we cannot compare our findings to another local survey.

Materials

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

15

The data for this study was collected through a 37 item online survey distributed through

Azusa Pacific Universitys email from the Center for Student Actions database. The survey

included questions using the Likert scale, demographic questions, and close ended questions. The

Likert scale was 1-5 with strongly disagree as 1 and strongly agree as 5. Since this survey was

specifically for an office on Azusa Pacific Universitys campus, we created a local survey

drawing from research previously done, the CAS standards, and goals set by the Center for

Student Action. The survey was reviewed and approved by the directors of the Center for Student

Action as well as our professor before it was sent out to the students. A copy of our survey can be

found in the appendix (Appendix A).

Four different categories of questions were used in the survey. First were questions

relating to participants involvement with CSA. These included (a) I signed up to volunteer

because my friends were already participating, (b) I signed up to volunteer because I wanted to

visit the country or community the ministry was located in, (c) I signed up to volunteer

because I have past experience volunteering, (d) I signed up to volunteer because I need to

complete service requirements to graduate, and more. These highlighted participants history of

volunteerism and involvement with CSA. The second category of questions related to CAS

standards for Service Learning Programs. CAS Standards for Service-Learning Programs (S-LP)

are highlighted through four different areas: diversity, program, leadership, and campus and

external relations. Statements were also on a 5 point Likert scale, from Strongly Disagree to

Strongly Agree. First, Diversity. CAS Standards state that S-LP must recognize, honor, educate,

and promote respect about commonalities and differences among people within their historical

and cultural contexts and also that S-LP must address the characteristics and needs of a diverse

population when establishing and implementing policies and procedures (Dean, 2009, pg. 355).

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

16

To assess this question, participants were prompted with the statement, (a) My motivation to

volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to engage with diverse communities.

Second, programming. CAS Standards states S-LP must offer a wide range of curricular and cocurricular service-learning experiences appropriate for students at all developmental levels and

with a variety of lifestyles and abilities (Dean, 2009, pg. 352). Participants were prompted to

evaluate this standard through the statement, (b) My motivation to volunteer with CSA is

influenced by the variety of programming the office provides. Third, leadership. CAS Standards

states many aspects of leadership for Service Learning Programs, including articulating vision

and mission, setting goals and objectives, advocating programs and services, and more (Dean,

2009, pg. 352). These standards were addressed to participants through the statement, (c) My

motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the leadership of the professional staff in the

office. Fourth, and finally, campus and external relations. CAS Standards state that SL-P must

reach out to relevant individuals, campus offices and external agencies to maintain relations,

share information, and coordinate and collaborate, where appropriate (Dean, 2009, pg. 355). This

standard was addressed to participants through the statement, (d) My motivation to volunteer

with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the community outside of

the university. These questions in the survey were designed to evaluate the Center for Student

Action through various CAS Standards for Service-Learning programs, helping identify more

motivating factors in student volunteerism. The third category of questions were based off of

themes in existing literature on motivations for volunteerism, such as (a) I seek opportunities to

engage in the community. (b) I have an desire to make an impact in society. (c) I volunteer to

develop my leadership abilities. (d) I volunteer to get out of my comfort zone. The fourth

category of questions were standard demographic questions in order to help specify our data

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

17

analysis. Participants were asked their Gender, Class Year, Major, Housing situation, Work, Race,

and Religion. Collectively, these questions helped create three distinct categories relating to

motivations for volunteerism with CSA: themes present in the literature (impact on individual,

university/community, and preparation for the future), CAS standards for Service Learning

Programs, and previous involvement with CSA.

Procedure

Participants were asked to fill out a 10-15 minute survey at their convenience and were

instructed to agree to the consent form before they could move on to the survey. The students

were also notified that if they completed the survey, they would be entered into a raffle to win

one of two gift cards. When the participants completed the survey and hit submit, it was

automatically reported into a Google spreadsheet which was transferred over to SPSS for

statistical analysis. The data was then analyzed through a variety of statistical tests in order to

answer the original research question of What are the motivators and benefits that influence

undergraduate college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a private faithbased institution?

Data was first analyzed using descriptive statistics in order to reveal the demographics of

the participant population. Frequencies were calculated for Gender, Class Year, Race, and

Religion (reported above). After demographic statistics were finished, overall means for the three

categories of questions were calculated. These categories are themes present in the literature

(impact on individual, university/community, and preparation for the future), CAS standards for

Service Learning Programs, and previous involvement with CSA. The highest scoring question

of each three category is reported below as the First Tier motivators. The second highest

scoring questions of each category are also reported as the Second Tier motivators. This helped

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

18

answer the research question of what are the main motivators that influence college students

volunteerism. After these were established, one way ANOVAs were calculated for each of the

four different involvement options (Local, Action Teams, Mexico Outreach, and Two or More

Teams) and the First Tier motivators. A one way ANOVA was also calculated for Second

Tier motivators, and significant differences were reported. These reveal more specific

motivators for college student volunteerism. Additional comparative statistics were calculated

between the demographic categories. Independent t-tests were calculated between First Tier

motivators and Gender, and between First Tier motivators and Race. A one way ANOVA was

calculated between Class Year and First Tier motivators. Together, this statistical analysis

reveals the main motivators and benefits that influence college students decisions to volunteer.

Results

Frequencies

Frequencies were calculated for demographic questions in order to gain a better

understanding of the sample for this study. Gender, Class Year, Race, and Religion were

calculated, and the frequencies are reported in the Methods section above. Participants

involvement is categorized in four different groups: Local, Action Teams, Mexico Outreach, and

Two or More Teams. Frequencies were calculated for each of these involvement groups prior to

comparative statistics (See Chart 1). 37 participants (17.2%) reported involvement with Local,

39 participants (18.1%) reported involvement with Action Teams, 84 participants (39.1%)

reported involvement with Mexico Outreach, and 55 participants (25.6%) reported involvement

with Two or More Teams.

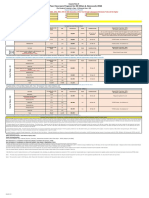

Chart 1: Pie Graph of Survey Samples Involvement with CSA

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

19

Table 1: Highest Scoring Motivators

First Tier and Second Tier Motivators (highest to lowest)

Question

Mean

Frequency (%)

I am motivated to volunteer because of my personal

values (Literature Review, first tier)

4.60

67.1%

145

I feel a sense of purpose when I volunteer (Literature

Review, second tier)

4.58

66%

142

My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by

the opportunity to build relationships with the

community outside the university. (CAS Standards, first

tier)

4.13

45.2%

98

I signed up to volunteer because I feel close to God when

I volunteer (Past experience with CSA, second tier)

3.98

41%

89

I signed up to volunteer because I have past experience

volunteering. (Past experience with CSA, first tier)

4.00

40.3%

87

My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by

the opportunity to engage with diverse communities

(CAS Standards, second tier)

3.92

37.5%

81

Table 2: One-Way ANOVA results for questions with significant differences between groups

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

I signed up to volunteer because I feel close to

God when I volunteer

20

N

Mean

Standard Deviation

Local Ministries

37

3.59

.985

Action Teams

39

3.85

.961

Mexico Outreach

84

4.10

.887

Two or More Teams

55

4.15

.951

Source

df

SS

MS

Between groups

8.81

2.94

3.37

.020

Within groups

211

184.07

.87

I signed up to volunteer because I feel close to

God when I volunteer

My motivation to volunteer with CSA is

influenced by the opportunity to engage with

diverse communities

Mean

Standard Deviation

Local Ministries

37

3.35

1.230

Action Teams

39

4.08

.929

Mexico Outreach

84

3.92

1.118

Two or More Teams

55

4.20

.970

Source

df

SS

MS

17.24

5.75

5.02

.002

My motivation to volunteer with CSA is

influenced by the opportunity to engage with

diverse communities

Between groups

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

Within groups

21

240.41

210

1.15

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

22

To figure out what are the main motivators and benefits of volunteerism, average means

were calculated for each category of questions in the survey: themes from the Lit Review, past

CAS Standard Themes, and experience volunteering with CSA. The highest scoring questions

are classified as First Tier motivators, and the second highest scoring questions are classified

as Second Tier motivators. All questions were based on a 5 point scale, making the highest

possible score a 5.

First Tier Motivators

The highest scoring question in the themes from the Lit Review category was I am

motivated to volunteer because of my personal values 145 out of 217 students reported

Strongly Agree (67.1%), (mean = 4.6). The highest scoring question in the CAS Standard

Theme category was My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to

build relationships with the community outside the university. 98 out of 217 students reported

Strongly agree (45.2%), (mean = 4.13). The highest scoring question in the Past experience

volunteering with CSA category was I signed up to volunteer because I have past experience

volunteering. 87 out of 217 students reported Strongly Agree (40.3%), (mean = 4.00). These

findings are summarized in Table 1.

Second Tier Motivators

The second highest scoring question in the Literature Review category was I feel a sense

of purpose when I volunteer 142 out of 217 students reported Strongly agree (66%), (mean =

4.58). The second highest scoring question in the CAS Standards Theme category was My

motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to engage with diverse

communities. 81 out of 217 students reported Strongly agree (37.5%), (mean = 3.92). The

second highest scoring question in the Past experience volunteering with CSA category was I

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

23

signed up to volunteer because I feel close to God when I volunteer 89 out of 217 students

reported Agree (41%), (mean = 3.98). These findings are summarized in Table 1.

Comparative Statistics

One way ANOVA.

A one-way ANOVA test was calculated between the First Tier motivators and

participant involvement (Local, Action Teams, Mexico Outreach, and Involvement in 2 or More

Teams). There was no significant difference between the four groups and I signed up to

volunteer because I have past experience volunteering (p = .258), My motivation to volunteer

with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the community outside the

university (p = .362), and I am motivated to volunteer because of my personal values (p = .

191). Therefore, none of the groups felt more strongly than the others that these motivators

influenced their decision to volunteer with CSA.

Another one-way ANOVA test was calculated between the Second Tier motivators and

the four different involvement groups. There was no significant different between the four groups

and I feel a sense of purpose when I volunteer (p = .812). There was a significant difference

between the four groups and I signed up to volunteer because I feel close to God when I

volunteer (p = .020) and My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the

opportunity to engage with diverse communities (p = .002).

An LSD post hoc test was calculated in order to identify which groups significantly

differed from each other regarding these two questions. For I signed up to volunteer because I

feel close to God when I volunteer, there was a significant difference between participants who

were involved with Local teams and participants who were involved with Mexico Outreach (p = .

007), and participants who were involved with 2 or more teams (p = .006). Participants who were

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

24

involved with Local teams averaged 3.59 for this question, Mexico Outreach averaged 4.10, and

Two or More Teams averaged 4.15. Therefore, Mexico Outreach and Two or more Teams felt

more strongly that their motivation to sign up to volunteer was because they feel close to God

when they volunteer. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

For My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to engage

with diverse communities, a significant difference was found between Local teams and Action

teams (p = .003), Mexico Outreach (p = .008), and 2 or More Teams (p = < .001). Local teams

averaged 3.35, Action Teams averaged 4.08, Mexico Outreach averaged 3.92, and Two or More

teams averaged 4.20. Therefore, Action Teams, Mexico Outreach, and Two or More Teams all

felt significantly strongly than Local Teams that their motivation to volunteer with CSA was

influenced by the opportunity to engage with diverse communities. These findings are

summarized in Table 2.

Independent Samples T-Test/One way ANOVA for Demographics.

Additional comparative statistics were calculated for demographic information reported

and the First Tier motivators.

An independent samples t-test was calculated between gender and the First Tier

motivators. There was no significant difference reported, concluding that men and women did

not differ in their motivation to volunteer for the First Tier motivators.

Race was recoded into two variables, White and Non-White in order to calculate an

independent t-test for the highest scoring questions. A one-way ANOVA could not be calculated

because at least one group in the Race variable had fewer than two cases. There was no

significant difference reported, concluding that White participants and participants of color did

not differ significantly in their agreement with the highest scoring questions.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

25

A one-way ANOVA test was calculated between class year and First Tier motivators.

There was a significant difference between the four groups and My motivation to volunteer with

CSA is influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the community outside the

university (p = .049). A post hoc test revealed the significant difference was between

Sophomores and Juniors, and Sophomores and Seniors. Sophomores reported an average of 3.80,

Juniors reported an average of 4.28, and Seniors reported an average of 4.27. Therefore, Juniors

and Seniors significantly agreed more with the statement My motivation to volunteer with CSA

is influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the community outside the

university than Sophomores. These results collectively revealed the strongest motivators and

benefits for undergraduate students decision to volunteer, as shown in the First Tier and

Second Tier motivators.

Discussion

The results of our research reveal three main points of discussion. First, there are

significant spiritual motivations for short-term volunteer trips that travel out of country. Second,

there is a significant motivation of location and diverse communities for participants who

volunteer with teams who travel out of country. Finally, demographic results reveal that

motivation to volunteer is not significantly different across gender or racial divides. Together,

these results help prompt areas of improvement for Center for Student Action and volunteer

programs at other colleges and universities.

The survey question I signed up to volunteer because I feel close to God when I

volunteer, showed a significant difference between Mexico Outreach and the other three

involvement options. Mexico Outreach had a significantly higher motivation for volunteering

because of the spiritual aspect of feeling closer to God. Although the Two or More Teams group

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

26

had a significantly higher difference, the survey data revealed that one of the multiple teams the

majority of the participants were involved in was Mexico Outreach. The spiritual aspect of

Mexico Outreach is clearly a motivating factor that plays a big part of students involvement

within the CSA. This shows that the majority of motivations found in the volunteers at the CSA

find closeness to God as a motivating factor when it comes to Mexico Outreach. What sets

Mexico Outreach apart from the other teams is that it is the only short-term volunteer

opportunity that travels outside of the country. Action Teams spend up to a month in another

country, while Local teams serve the local community around APU. A primary motivator to

volunteer in Mexico Outreach specifically is the closeness to God, which comes through an

international short-term volunteer opportunity.

Next, results revealed that local and the opportunity to engage with diverse communities

is strong motivator in why students choose to volunteer. A Second tier motivator, My

motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to engage with diverse

communities, showed a significant difference between Local Ministries and all of the other

teams (Mexico Outreach, Action Teams, and Two or More Teams). The students who filled out

the survey said they were more motivated by the opportunity to engage with diverse

communities when they were a part of all of the teams except Local Ministries. This finding

reveals that location is a big factor for students who volunteer at the CSA. Local Ministries are

the other CSA volunteer opportunity in the survey which does not travel internationally.

Therefore, location is also a primary motivator for why students choose to engage in

volunteerism.

Along with the opportunity to visit new locations, participants are also given the

opportunity to engage with diverse communities. The two second tier motivators which

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

27

revealed significant differences between groups support this conclusion. The program of Mexico

Outreach, for example, has a high volume of students who want to be closer to God as well as

being able to visit Mexico and engage with their community. This manifests itself in the many

practical service opportunities students engage with while in Mexico. With the Action Teams, the

significance was found was engaging in diverse communities. As Actions teams visit other

countries, they are also given the opportunity to engage with diverse communities abroad. This

second tier motivator does not say for sure that this is the case and needs further research to

support this. However, it can be assumed that the idea of visiting or touristing plays a

significant part in motivation for students at the CSA.

The demographic data revealed interesting findings regarding the year in school the

students reported and the top tier motivator, My motivation to volunteer with CSA is

influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the community outside the university.

Juniors and Seniors found a much higher motivation to volunteer because of the motivator,

building relationships outside of the university. Older students may also have a better

understanding of the Center and the surrounding community, thus creating credibility and

familiarity when deciding to volunteer with CSA or another opportunity. However, there was no

significant difference between gender and race/ethnicity, which means that the CSA has recruited

a wide variety of students who all share the same passion and motivation to volunteer. This is

important to keep in mind as CSA continues to recruit students for their volunteer opportunities,

as any student may be motivated as the next student to volunteer with them.

The CSA does a remarkable job of keeping students motivated for reasons that align with

the previously stated learning outcomes. Mexico Outreach and Action Teams do significant work

in creating a culture that shows significant students motivation aligns with learning outcomes

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

28

the Center works towards. There is a strength seen in the program in how it deals with creating a

culture in the global minded programs. The learning outcomes that center on Christ and

Community are seen in the both the top tier and second tier motivators. Although the

learning outcomes centered on Service and Scholarship do not seem to be a strong motivating

factor, it plays a role in what the CSA can do moving forward. The CSA also met CAS Standards

for campus/external relations and diversity. Leadership and Programming, the other two CAS

Standards reviewed in this study, can be improved within CSA through implementing new

service opportunities or restructuring existing ones, such as Local Ministries.

There are growth areas as seen in the results of the survey. The Local Ministries part of

the CSA does not seem to have a culture that has been built up within the students that have

participated in it. There was not any significance that showed motivation being a major factor for

those being a part of Local Ministries. This shows that the culture within those students is not the

same that it is for other programs in the CSA. There is also a growth area that is found with

different age groups. The CSA seems to have a great relationship with juniors and seniors and

find the motivating factors more significant with them but with sophomores there is a lack of

connection to some of the motivators. The office can grow through connecting with younger

students on campus.

The staff in the CSA has already started taking steps in working on these growth areas

and results will confirm their progress. The CSA is starting to connect with the younger students

on campus in hiring entry level student positions. These will allow first year and second year

students to get more involved with the Center. These positions will work to create culture and

motivation in all aspects. Local Ministries is also revamping their structure to increase quality

and decrease quantity. This will help to provide a better experience and begin to build up

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

29

credibility within the Local teams, which would lead to the top tier motivators mentioned in

this survey. These changes, along with others, will help the CSA reach their full potential and

increase volunteerism across the campus.

Conclusion

This research study sought to answer the question of what motivates college students to

engage in volunteer opportunity at their institution. By analyzing quantitative data from a survey

sent out to students who have volunteered with the Center for Student Action at APU, several

conclusions were reached. It was discovered that primary motivators for APU students to

volunteer centered on closeness to God and spiritual aspects of volunteerism, along with

opportunities to visit new locations and engage with diverse communities. These motivators

align with the CSAs learning outcomes for students, and strengthened the credibility of the

center on campus.

Further research could explore primary motivators for students at non-faith based

institutions, large research-based schools, or even expanding to non-traditional students. Because

our sample was very specific, conclusions may not be applicable to larger audiences. However, it

is interesting to note the primary motivators to volunteer from participants in our study, not only

to support the work the CSA is doing on campus, but also as encouragement that emerging

adults have not strayed away from volunteerism. It continues to be an important part of an

individuals development, with benefits both for the community a student serves, and the student

themselves. As colleges and universities continue to make changes to strengthen their institution

and their student body, it is vital that students are invited to participate in volunteer opportunities.

Institutions can be assured that their student body is motivated to serve both the college and its

greater community as well.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

30

References

Anyon, Y., Gardner, J. W., & Fernandez, M. A. (2007). Realizing the potential of communityuniversity partnerships. Change, 39(6), 40-45.

Beehr, T.A., LeGro, K., Porter, K., Bowling, N.A., & Swader, W. M. (2010). Required

volunteers: Community volunteerism among students in college classes. Teaching of

Psychology, 37(4), 276-280. doi: 10.1080/00986283.2010.510965

Bowman, N., Brandenberger, J., Lapsley, D., Hill, P., & Quaranto, J. (2010). Serving in college,

flourishing in adulthood: Does community engagement during the college years predict

adult well-being?. Applied Psychology: Health & Well-Being, 2(1), 14-34.

doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01020.x

Brady, L., & Hapenny, A. (2010). Giving back and growing in service: Investigating spirituality,

religiosity, and generativity in young adults. Journal of Adult Development, 17(3), 162167. doi: 10.1007/s10804-010-9094-7.

Center for Student Action Learning Outcomes. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.apu.edu/studentaction/about/outcomes/

Dean, L. A., & Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2009). CAS

professional standards for higher education.

Droege, J. R., & Ferrari, J. R. (2012). Toward a new measure for faith and civic engagement:

Exploring the structure the FACE scale. Christian Higher Education, 11(3). 146-157.

doi:10.1080/15363751003780852

Fajardo, I., Lott, J. L., & Contreras, F. (2014). Volunteerism: Latina/o students and private

college experiences. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 13(3), 139-157.doi

10.1177/1538192713516632

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

31

Griffith, J., & Thomas, T. (2014). Do college youth serve others/how and under which

circumstances? Implications for promoting community service. New Directions For

Institutional Research, 2014(162), 29-42. doi:10.1002/ir.20075

Hellman, C. M., Hoppes, S., & Ellison, G. C. (2006). Factors associated with college student

intent to engage in community service. Journal of Psychology, 140(1), 29-39.

Hoffman, A.J. (2012). The relationship among higher education, community service work

activities and connectedness: Simply a matter of doing more and expecting less.

Making Connections: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cultural Diversity, 12(2), 46-53.

http://organizations.bloomu.edu/connect/

Holdsworth, C. (2014). Volunteering, choice and control: A case study of higher education

student volunteering. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(2), 204-219. doi:

10.1080/13676261.2013.815702

Holdsworth, C., & Quinn, J. (2012). The epistemological challenge of higher education student

volunteering: Reproductive or deconstructive volunteering? Antipode, 44(2), 386405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00844.x.

Kozlowski, C., Ferrari, J. R., & Odahl, C. (2014). Social justice and faith maturity: Exploring

whether religious beliefs impact civic engagement. Education, 134(4). 427-432.

Littenberg-Tobias, J. (2014). Does how students serve matter? What characteristics of service

programs predict students social justice attitudes? Journal of College & Character,

15(4), 219-233. doi:10.1515/jcc-2014-0027.

Moore, E.W., Warta, S., & Erichsen, K. (2014). College students volunteering: Factors related

to current volunteering, volunteer settings, and motives for volunteering. College Student

Journal, 48(3), 386-396.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

32

OLeary, L. S. (2014). Civic engagement in college students: Connections between involvement

and attitudes. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2014(162), 55-65. doi:

10.1002/ir.20077

Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D., & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and

commitments to community service in college: A multidimensional conceptual model.

Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338.

Schuh, J.H. (2008). Assessment methods for student affairs. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sullivan, S. C., Ludden, A. B., & Singleton, J. A. (2013). The impact of institutional mission on

student volunteering. Journal Of College Student Development, 54(5), 511.

Trudeau, K.J., Delvin, A.S. (1996). College students and community service: Who, with whom

and why? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(21), 1867-1888. doi: 10.1111/j.15591816.1996.tb00103.x

Weston, L. A. (2013). What are you doing this summer? CollegeXpress Magazine, Spring 2013,

25-27.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

33

APPENDIX A

Copy of Survey Questions

Motivators and Benefits of Volunteer Service in College Students

The purpose of this study is to look at why college students choose to volunteer, and the impact

of service learning opportunities. Your participation in this study will help Student Affairs

Professionals learn about volunteer service among students, and also help students understand

themselves. An informed consent form for this research is below. After completing it, you will be

taken to the full survey, which should take about 10-15 minutes. Thank you for your time and

participation!

- Ryan Bishop, Sara Hogue, Danny Ledezma, & Leah Sadoian

Informed Consent

I am being asked to participate in a research project conducted by Ryan Bishop, Sara Hogue,

Danny Ledezma and Leah Sadoian in the School of Behavioral and Applied Sciences, Azusa

Pacific University (APU). I am being asked because my opinions will help Student Affairs

Professionals understand the motivating factors behind why college students volunteer. This

study is student-initiated and will be used to satisfy the completion of a graduate level course.

PURPOSE: The purpose of this study is to look at why college students choose to volunteer, and

the impact of service learning opportunities. The goal of this study is to identify the main factors

that influence undergraduate college students decisions to participate in volunteer service at a

private, faith-based institution.

PARTICIPATION: I agree to complete a survey that ask about my history of volunteer service,

interaction with the Center for Student Action (CSA) at APU, and why I choose/not choose to

volunteer. The time estimated for completing the survey is about 10 minutes.

RISKS & BENEFITS: The potential risks associated with this study are very minimal, including

personal inconvenience associated with filling out a survey and mild discomfort at thinking

through ones decision to volunteer. We expect this research to benefit society by helping

students understand themselves better.

COMPENSATION: There is no compensation for participating in this research project.

VOLUNTARY PARTICIPATION: Please understand that participation is completely voluntary.

My decision whether or not to participate will in no way affect my current or future relationship

with APU or its faculty, students, or staff. I have the right to withdraw from the research at any

time without penalty. I also have the right to refuse to answer any question(s) for any reason,

without penalty.

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

34

CONFIDENTIALITY: The information collected will remain confidential within the constraints

of state and federal law. Our responses will be totaled and combined with the responses of other

participants and the results will only be used within the context of a graduate level class at APU.

We will collect individual emails in order to notify the winners of the raffle.

If you have any questions, or would like additional information about this research, please

contact one of the researchers at the emails below. You can also contact our professor, Dr. Holly

Holloway-Frisen at hfriesen@apu.edu.

Researcher Contact Information:

Ryan Bishop: ryanbishop87@gmail.com

Sara Hogue: shogue13@apu.edu

Danny Ledezma: dledezma14@apu.edu

Leah Sadoian: lsadoian13@apu.edu

I understand the above information and have had all of my questions about participation

in this research project answered. I voluntarily consent to participate in this research

- I give my consent to participate in this research

In relation to my experience volunteering through the Center for Student Action

I am involved in

-

Local Ministries

Action Team

Mexico Outreach

Other

The following survey questions are on a 1-5 scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly

Agree

1.

I signed up to volunteer

because my friends were already participating

2.

I signed up to volunteer

because I wanted to visit the country or community the ministry was located in

1.

I signed up to

volunteer because I wanted to visit the country or community the ministry was located in

2.

I signed up to

volunteer because of a spiritual experience at chapel

3.

I signed up to

volunteer because I feel close to God when I volunteer

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

35

4.

I signed up to

volunteer because I had prior knowledge of the country or community the ministry was

located in

5.

I signed up to

volunteer because I had past experience with a specific CSA ministry

6.

I signed up to

volunteer because I have past experience volunteering

7.

I signed up to

volunteer because I need to complete service requirements to graduate

8.

I signed up to

volunteer because I have a class project requirement

9.

I signed up to

volunteer with the CSA because of my experience with City Links

10.

The information

received on Cougar Walk at a table influenced my decision to volunteer with CSA

11.

The information

received through APU 411 influenced my decision to volunteer with CSA

14. My motivation to volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to engage with diverse

communities

12.

My motivation to

volunteer with CSA is influenced by the variety of programming the office provides

13.

My motivation to

volunteer with CSA is influenced by the leadership of the professional staff in the office

14.

My motivation to

volunteer with CSA is influenced by the opportunity to build relationships with the

community outside of the university

18. I seek opportunities to engage in the local community

1.

I have a desire to make an impact in society

2.

I volunteer to develop my leadership abilities

3.

I volunteer to get out of my comfort zone

4.

Volunteering has increased my knowledge of social justice in

the world

5.

I am motivated to volunteer because of my personal values

6.

I feel encouraged by my school to volunteer

7.

I feel a sense of purpose when I volunteer

8.

I feel a sense of reward when I volunteer

9.

I volunteered in high school to strengthen my college

application

MOTIVATING STUDENTS TO VOLUNTEER

10.

I volunteer in college so I will be more employable after I

graduate

29. What is your gender?

a.

b.

11.

a.

b.

c.

d.

12.

13.

a.

b.

14.

a.

b.

15.

a.

b.

c.

16.

a.

b.

17.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

g.

18.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

g.

Male

Female

What is your class year?

Freshman

Sophomore

Junior

Senior

What is your major?

Do you live on-campus?

Yes

No

Do you currently have a job?

Yes

No

On average, how many hours do you work per week?

0-10 hours

11-29 hours

30 hours or more

Where is your job located?

On-campus

Off-campus

What is your race?

American Indian or Alaska Native

Asian

Black or African American

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

White

Multi-Racial

Other

What is your religion?

Christian

Muslim

Buddhist

Folk Religion

Sikh

Unaffiliated

Other

36

You might also like

- Final Action PlanDocument15 pagesFinal Action Planapi-280536751No ratings yet

- New ResumeDocument2 pagesNew Resumeapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Hle Flyer - Race RepresentationDocument1 pageHle Flyer - Race Representationapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Culmination PaperDocument10 pagesCulmination Paperapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Crisis Management Final Exam SadoianDocument7 pagesCrisis Management Final Exam Sadoianapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Diversitytraining rd1Document7 pagesDiversitytraining rd1api-280536751No ratings yet

- Budget ProposalDocument5 pagesBudget Proposalapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Institutional Responses PaperDocument10 pagesInstitutional Responses Paperapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Brittney Barron ContractDocument4 pagesBrittney Barron Contractapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Helms PowerpointDocument16 pagesHelms Powerpointapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Faculty Interview Paper LeahsadoianDocument9 pagesFaculty Interview Paper Leahsadoianapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Staffmeetingoctober132015 1Document2 pagesStaffmeetingoctober132015 1api-280536751No ratings yet

- Hearing Notification Template-1-2Document2 pagesHearing Notification Template-1-2api-280536751No ratings yet

- Brittney Barron ContractDocument4 pagesBrittney Barron Contractapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Ard Presentation 10 30 15Document18 pagesArd Presentation 10 30 15api-280536751No ratings yet

- Personal Theory of Helping PaperDocument13 pagesPersonal Theory of Helping Paperapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Leaheventevaluation 2Document3 pagesLeaheventevaluation 2api-280536751No ratings yet

- SCRD Meeting Dev DiscussDocument2 pagesSCRD Meeting Dev Discussapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Leahsadoian Designning Programming AssignmentDocument7 pagesLeahsadoian Designning Programming Assignmentapi-280536751No ratings yet

- Core Values Ethics PaperDocument7 pagesCore Values Ethics Paperapi-280536751No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sandy Shores: Sink or FloatDocument5 pagesSandy Shores: Sink or FloatElla Mae PabitonNo ratings yet

- T04S - Lesson Plan Unit 7 (Day 3)Document4 pagesT04S - Lesson Plan Unit 7 (Day 3)9csnfkw6wwNo ratings yet

- Book Edcoll 9789004408371 BP000012-previewDocument2 pagesBook Edcoll 9789004408371 BP000012-previewTh3Lov3OfG0dNo ratings yet

- Bulgaria Lesson Plan After LTT in SpainDocument3 pagesBulgaria Lesson Plan After LTT in Spainapi-423847502No ratings yet

- DLL English-4 Q1 W8Document5 pagesDLL English-4 Q1 W8Shiera GannabanNo ratings yet

- Dalcroze LessonDocument2 pagesDalcroze Lessonapi-531830348No ratings yet

- 1.1 Physical Qualtities CIE IAL Physics MS Theory UnlockedDocument6 pages1.1 Physical Qualtities CIE IAL Physics MS Theory Unlockedmaze.putumaNo ratings yet

- Insurance List Panipat 4 OCTDocument21 pagesInsurance List Panipat 4 OCTpark hospitalNo ratings yet

- The Four Corner Vocabulary ChartDocument4 pagesThe Four Corner Vocabulary ChartgetxotarraNo ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT2 - Question - MAT183 - MAC2023Document5 pagesASSESSMENT2 - Question - MAT183 - MAC2023Asy 11No ratings yet

- FIITJEE1Document5 pagesFIITJEE1Raunak RoyNo ratings yet

- UDM Psych Catch Up The Clinical Interview and Process RecordingDocument70 pagesUDM Psych Catch Up The Clinical Interview and Process RecordingRhea Jane Quidric BongcatoNo ratings yet

- How To Speak Fluent EnglishDocument7 pagesHow To Speak Fluent Englishdfcraniac5956No ratings yet

- Protein Synthesis QuestionarreDocument2 pagesProtein Synthesis QuestionarreRiza Sardido SimborioNo ratings yet

- Computer Studies Form 3 Schemes of WorkDocument24 pagesComputer Studies Form 3 Schemes of Workvusani ndlovuNo ratings yet

- Textbook Replacement Information and Parent LetterDocument2 pagesTextbook Replacement Information and Parent Letterapi-194353169No ratings yet

- Elements of NonfictionDocument2 pagesElements of Nonfiction본술파100% (1)

- Implementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation AlgorithmDocument5 pagesImplementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation Algorithmpurushothaman sinivasanNo ratings yet

- 1 Host - Event RundownDocument2 pages1 Host - Event RundownMonica WatunaNo ratings yet

- List of Public Administration ScholarsDocument3 pagesList of Public Administration ScholarsSubhash Pandey100% (1)

- Geoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LDocument173 pagesGeoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LPieroZizzaniaNo ratings yet

- Catrina Villalpando ResumeDocument1 pageCatrina Villalpando Resumeapi-490106460No ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae - Updated May 2020Document6 pagesCurriculum Vitae - Updated May 2020api-513020529No ratings yet

- Railway Recruitment Board: Employment Notice No. 3/2007Document4 pagesRailway Recruitment Board: Employment Notice No. 3/2007hemanth014No ratings yet

- PIDS Research On Rethinking Digital LiteracyDocument8 pagesPIDS Research On Rethinking Digital LiteracyYasuo Yap NakajimaNo ratings yet

- More Theatre Games and Exercises: Section 3Document20 pagesMore Theatre Games and Exercises: Section 3Alis MocanuNo ratings yet

- 05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasDocument18 pages05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasFghNo ratings yet

- IBM Thinkpad R40 SeriesDocument9 pagesIBM Thinkpad R40 SeriesAlexandru Si AtatNo ratings yet

- SecA - Group1 - Can Nice Guys Finish FirstDocument18 pagesSecA - Group1 - Can Nice Guys Finish FirstVijay KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Cover Page Work Immersion Portfolio 1Document7 pagesCover Page Work Immersion Portfolio 1Rosalina AnoreNo ratings yet