Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Angst, J - Historical Aspects of Manic Depression & Schizophrenia, (2002) 571 Schizophrenia Research 5

Uploaded by

FulguraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Angst, J - Historical Aspects of Manic Depression & Schizophrenia, (2002) 571 Schizophrenia Research 5

Uploaded by

FulguraCopyright:

Available Formats

Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 5 13

www.elsevier.com/locate/schres

Historical aspects of the dichotomy between

manicdepressive disorders and schizophrenia

Jules Angst *

Epidemiological Research, Zurich University Psychiatric Hospital, Lenggstrasse 31, Mail Box 68, 8029 Zurich, Switzerland

Abstract

The history of psychiatric classification is highly complex and this presentation must be restricted to a simplified overview.

Guislain [Guislain, J., 1833. Traite des phrenopathies ou doctrine nouvelle des maladies mentales. Etablissement

rztl. Ver. 7 (1837) 321] established a unitarian

Encyclopedique, Brussels] and Zeller [Beil. Med. Corresp.-Bl. Wurtemb. A

concept of psychiatric disorder, permutations of which have survived until the present day. Kraepelins [Kraepelin, E., 1899.

rzte (6th edn.). Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig] dichotomy between

Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und A

manic depressive insanity and dementia praecox was built mainly on Kahlbaums [Kahlbaum, K., 1863. Die Gruppirung

der Psychischen Krankheiten und die Eintheilung der Seelenstorungen. AW Kafemann, Danzig] classification, which took

clinical symptoms, course and outcome into account. Kraepelins well-accepted approach sought to provide a basis for

diagnosis, prognosis, choice of treatment and causal research. Kraepelins dichotomy came to be questioned on several grounds:

(1) doubts about his unification of bipolar disorder [Gaz. Hop. 24 (1851) 18] with melancholia, (2) doubts about the

significance of Kraepelins diagnostic groups for causal research [Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 12 (1912) 540], illustrated best

by the work of Bonhoeffer [Bonhoefferm, K., 1912. Die symptomatischen Psychosen im Gefolge akuter Infektionen,

Allgemeinerkrankungen und innerer Krankheiten. In: Aschaffenburg, G. (Ed.), Handbuch der Psychiatrie, 3. Abt., 1. Halfte.

Deuticke, Leipzig Wien], (3) the complex psychopathological descriptions and classifications of numerous subgroups of

psychoses by Kleist [Monatsschr. Psychiatr. Neurol. 125 (1953) 526] and Leonhard [Leonhard, K., 1968. Aufteilung der

endogenen Psychosen (4th edn.). Akademie Verlag, Berlin] and (4) description of the psychoses between affective and

schizophrenic disorders (intermediate psychoses, mixed psychoses, schizo-affective psychoses) beginning with Kehrer and

Kretschmer [Kehrer, F., Kretschmer, E., 1924. Die Veranlagung zu seelischen Storungen. (Monographien aus dem

Gesamtgebiete der Neurologie 40) Springer, Berlin] and persisting up to the modern findings of a continuum between the two

major groups of psychiatric disorders. Kraepelins simplification has so far been more successful than the Kleist Leonhard

approach, but the modern and more descriptive trend in psychiatric classification favours the syndromal concept of Hoche and

the concepts of continua between affective and schizophrenic disorders and between normal and pathological behaviour.

D 2002 Published by Elsevier Science B.V.

Keywords: History; Classification; Schizophrenia; Schizo-affective disorder; Affective disorder

1. Unitarian concepts of psychiatric classification

Tel.: +41-1-384-26-11; fax: +41-1-384-24-46.

E-mail address: jangst@bli.unizh.ch (J. Angst).

A generally accepted classification system for psychiatric disorders did not exist until the end of the 19th

century. Before Kraepelin, the situation was confused.

0920-9964/02/$ - see front matter D 2002 Published by Elsevier Science B.V.

PII: S 0 9 2 0 - 9 9 6 4 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 3 2 8 - 6

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

In his historical review, Kahlbaum (1863) summarised

about 30 different systems of classification from Plater

(1625), considered to be the founder of medical and

psychiatric classification, to Morel (1851). One such

attempt to describe or classify psychiatric symptoms or

syndromes was made by Guislain (1833) in Belgium,

who devised a complex system consisting of a mosaic

of about a hundred different states. Guislain considered the cause of all psychiatric disturbances to be

consequences of psychic pain (douleur moral, Seelenschmerz), ultimately resulting in dementia. A stressor model of psychiatric disorder was implicit in

Guislains unitarian causal theory.

A logical consequence was the concept of unitary

psychosis, the history of which has been extensively

described by Vliegen (1980) and recently by Berrios

and Beer (1992, 1994). Zeller (1837), who translated

the work of Guislain, was the founder of the concept

of unitary psychosis, comprising all psychotic syndromes, which he regarded as representing no more

than different stages of a pathological process, itself

the result of an interaction of somatic and psychological factors. Other important proponents of the unitary

psychosis were Griesinger (1845), an assistant of

Zeller, and Neumann (1859). Jacksons evolutionary

view of the formation of a functional hierarchy of the

brain was influential on more recent developments

(Berrios and Beer, 1992). In his review of the unitary

psychosis, Maier (1992) notes that like Griesinger but

over a century later, Ey (1963) developed a hierarchical model based on the evolution of the brain as did

Foulds and Bedford (1975) on the basis of interpersonal communication. Another 20th century exponent of the unitary psychosis was Rennert (1965),

who developed the concept of the universal origin

(Universalgenese) of endogenous psychoses. He

explicitly set out to challenge the efforts by Wernicke,

Kleist and Leonhard to devise a sophisticated

diagnostic atomisation. The psychopathological

concepts developed by Janzarik (1969) are also compatible with a unitarian theory.

2. Forerunners of Kraepelins dichotomy

Although one source of Kraepelins dichotomy of

manic depressive insanity and dementia praecox is

probably the distinction drawn by Griesinger between

disorders of affects and ideas/will (Vliegen, 1980),

there can be little doubt that Kraepelin (1918) based

his concept chiefly on the work of Kahlbaum, who

had introduced a dichotomy based on course and

outcome, a debt he later came to acknowledge himself.

In 1863, Karl Kahlbaum published his monograph

The grouping of psychological illnesses and the

classification of mental disorders, on which the

edifice of modern nosology is built. On the basis of

symptoms, course and outcome, Kahlbaum distinguished between two large groups of mental disorders: vecordia was a limited disturbance and

vesania a complete disturbance of the mind (Table

1). The first group was characterised by a continuous

but remitting course, by continuous he meant that

the symptom complexes or states did not change their

typical symptoms over time (Kahlbaum, 1878, p.

1145). The benign group of vecordia comprised

vecordia dysthymia, which included depression

and mania. By contrast, the course of vesania showed

a changing symptomatology, was progressive and the

outcome was dementia. Vesania consisted of vesania

typica (from which dementia praecox was later

derived) and vesania progressiva, which embraced

all brain disorders such as progressive paralysis and

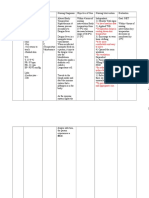

Table 1

Classification of psychotic disorders by Kahlbaum (1863)

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

Table 2

Classification of mood disorders by Kahlbaum (1882)

Cyclothymiaa

Vesania typica circularisb

. Dysthymiac

. Hyperthymiae

. Melancholiad

. Maniaf

a

b

c

d

e

f

Mood disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder.

Depression, dysthymia.

Schizo-depression.

Mania, hypomania.

Schizo-bipolar/mania.

stroke (Table 1). Later in 1879, Kahlbaum added

catatonia as a subgroup of vesania.

In 1882, he renamed vecordia dysthymia cyclothymia, which comprised dysthymia (Flemming,

1844) and hyperthymia (Table 2). The terms cyclothymia, dysthymia and hyperthymia were used by

Kahlbaum in order to distinguish remitting affective

disorders from melancholia and mania (as stages of

the vesania typica circularis) with a poor outcome.

From todays perspective, these two groups appear as

a clear description of mood disorders and schizoaffective disorders. The classification system proposed by Kahlbaum was not very successful; the

new terms that he introduced in order to separate

disorders with a good outcome from those ending in

dementia were too numerous.

3. Emil Kraepelins dichotomy

Emil Kraepelins first nosological publication was

his programmatic Compendium of 1883. As Roelcke

(1996) pointed out, Kraepelin put forward a classification based on putative somatic causation of psychiatric diseases, which was a complete break with

tradition. Kraepelin sought to establish psychiatry on

the basis of the natural sciences, adhering to an

experimental model, inspired by his teacher Wilhelm

Wundt and the results of his own first psychopharmacological study (Kraepelin, 1882, 1883). But Kraepelin also recognised our ignorance of the causation of

psychiatric disorders, which (as today) made it impossible to consider complexes of symptoms (syndromes)

as disorders. Kraepelin wanted to create a nosology

that would provide a basis for successful prognosis,

therapy, and prevention (Roelcke, 1997). For this

purpose, Kraepelin systematically compiled informa-

tion on symptomatology, family history, and the longterm course of the patients condition.

A significant breakthrough came with the fifth

edition of Kraepelins (1896) textbook, in which the

author conceptualised disease entities on the basis of

causation, symptoms, course and outcome and in

which he published a comprehensive chapter on

dementia praecox. In a presentation given the same

year in Heidelberg and published in 1897, Kraepelin

stressed the prognostic value of an early diagnosis,

validated by a careful long-term follow-up. In such a

way, he maintained, one could distinguish processes

leading to dementia from others. He also separated

depression from involutional melancholia.

A more elaborate classification was published in

the sixth edition of Kraepelins (1899) textbook,

where he integrated into the group of dementia

praecox the catatonia of Kahlbaum (1874), the

hebephrenia of Hecker, which was conceptionalised

by Kahlbaum (Hecker, 1871), and dementia paranoids. Among other disorders Kraepelin distinguished

dementia praecox from involutionary psychosis,

manic depressive insanity and paranoia as further

diagnostic categories (Table 3).

In comparison with Kahlbaum, Kraepelins terminology was simpler and his comprehensive text much

easier to read and to understand. It dispelled the

confusion that prevailed in contemporary psychiatric

classification, a task in which Kahlbaum had had little

success. The success of Kraepelins dichotomy experienced later a revival in the United States in the

Neo-Kraepelinian school of St. Louis with the

introduction of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer et al., 1978) as syndromal constructs (Kick, 1981).

Kraepelins influential classification did not however go unchallenged. Three developments in the

intervening century have cast serious doubts on Kraepelins dichotomy: the first relates to the classification

of affective disorders, the second to intermediate,

Table 3

Krapelins 1899 classification

.

.

.

.

.

.

Dementia praecox (hebephrenia, catatonia dementia paranoids)

Manic depressive insanity

Dementia paralytica

Insanity and brain diseases

Involutional psychosis

Paranoid states

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

Table 4

History of classifying affective disorders

olar psychoses. Kleist considered both mania and

depression to be monopolar psychoses and bipolar

psychosis to be due to a specific affiliation of the

two. The concept of bipolar psychosis propounded by

Kleist and his pupil Leonhard (1968) therefore differs

clearly from the concept current today, which subsumes monopolar mania under bipolar disorder. The

modern concept is mainly based on research carried

out in the 1960s (Angst, 1966; Perris, 1966; Winokur

et al., 1969), which established the distinction between

bipolar disorder and monopolar/unipolar depression

on the basis of course and genetics. With this development, Kraepelins dichotomy was questioned at least

in the field of manic depressive insanity.

5. Intermediate psychosis, mixed psychosis,

schizo-affective psychosis

mixed or schizo-affective disorders and the third

questions the validators of the dichotomy and suggests

a continuum concept of functional psychoses.

4. Bipolar disorder and unipolar depression

The history of the classification of affective disorders is briefly summarised in Table 4. From antiquity

right up until the middle of the 19th century, melancholia and mania were generally considered to be two

completely different disorders, of physical origin,

embracing all types of psychiatric syndromes including all organic brain disorders, schizophrenia and

affective disorders. As Pichot (1995) has established,

the alternation of mania and depression was accurately

described by Esquirol in 1838 but was not considered

to be a single disorder. It is to Falret that we owe the

creation of the concept of manic depressive disorder.

In 1851, Falret working in Paris (interesting details

were published by Haustgen, 1993) developed the term

la folie circulaire to describe what he considered to

be a new and separate psychiatric disorder. Kraepelin

was aware of Falrets concept but deliberately unified

mania, depression and bipolar disorder into one broad

category of manic depressive insanity. In the-mid

20th century, Kleist (1953) challenged Kraepelins

model with his distinction between bipolar and monop-

A second development, the development of the

concept of schizo-affective psychosis, undermined the

dichotomy in a more central point. As mentioned

earlier, a weak point of both Kahlbaum and Kraepelins dichotomy is that they classified manic and

depressive syndromes among both major psychoses:

manic depressive insanity and dementia praecox.

This resulted in schizo-affective states being subsumed under vesania typica, under dementia praecox

and later under schizophrenia. Table 1 demonstrates

how, in regard of affective syndromes, the dichotomy

remained ambiguous. Little wonder that Kahlbaum

and Kraepelin both noticed the existence of intermediate cases.

This gap was filled in the 1920s when the concept

of intermediate psychosis (mixed psychosis) was

developed by Kehrer and Kretschmer (1924) and

Gaupp and Mauz (1926). In 1933, Kasanin, coined

the term schizo-affective psychoses for a subgroup of

schizophreniform psychoses with a good prognosis

and simultaneous presence of schizophrenic and affective syndromes. This simultaneous co-occurrence

required for diagnosis is a constant and has been

maintained in the Diagnostic Manuals ICD-10 and

DSM-IV. Schizo-affective disorders have been defined

in a variety of ways (analysed for instance, by Brockington and Leff, 1979 who demonstrated the polymorphism of the group and the low concordance

between the concepts).

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

The modern cross-sectional concept of schizo-affective disorder suffers from the shortcoming that it does

not take into account the even more puzzling longitudinal change of syndromes, the transition of manic

depressive to paranoid or schizophrenic disorders.

(Schule, 1878; Urstein, 1909; Stransky, 1911; Smith,

1925; Mayer-Gross, 1932) or vice versa the change of

schizophrenic syndromes into manic depressive syndromes (Hoffmann, 1925; Mayer-Gross, 1932).

Kretschmer (1919) disputed the whole notion of the

existence of two separate disorders and described

circular insanity and schizophrenia as disorders of

the same stratum (Schicht). Bleuler (1922) transitionally shared Kretschmers opinion, agreeing with his

assumption of a continuum from normal to pathological in the dimensions schizothymic schizoid schizophrenic, cyclothymic (syntonic) cycloid and circular

manic depressive. Bleuler assumed that both forms of

disposition co-existed independently in every human

individuum. A differential diagnosis between schizophrenia and manic depressive insanity had therefore

to be questioned in principle. Gaupp (1939) considered

it as natural to have mixtures of symptoms of both

major psychoses.

It should not be forgotten that Kraepelin (1920)

himself came to express concern about the dichotomy,

admitting that, No expert will deny that cases which

cannot be classified safely are disturbingly frequent

(unerfreulich haufig). . . We will have to get used to

the idea that all signs are insufficient to delineate

manic depressive insanity from schizophrenia. . . .

and that overlap occurs.

Under Kretschmers influence, the dichotomy

seemed moribund and Birnbaum (1928) predicted that

nosology had come to a dead end, a point on which he

agreed with Bumke (1925). Bumke (1924) argued that

rather than Kraepelins disease entities only a typology of psychiatric syndromes was feasible, a view

which was shared by Kretschmer (1929) and later by

Schneider (1967).

6. The continuum from affective to schizophrenic

syndromes

A decisive contribution came from Hoche (1912),

who criticised the view of schizophrenia as a disorder.

Hoche distinguished between disorders, symptom

complexes (syndromes) and elementary symptoms

and maintained that psychiatric disorders such as

dementia praecox could be no more than analogies

to diagnostic groups of somatic medicine and that in

reality dementia praecox was characterised by a

chaotic symptomatology. Hoche advanced the theory

that psychiatric syndromes expressed dispositions or

reaction patterns, for instance hysterical, hypochondriacal, neurasthenic, manic, depressive or paranoid.

In fact, it is the symptomatological change (Janzarik,

1968) and not the stability that characterises the longterm course of psychotic disorders and none of the

European long-term studies on schizophrenia has

found symptomatological stability (Bleuler, 1972;

Ciompi and Muller, 1976; Huber et al., 1979; Marneros et al., 1991).

Hoches syndromal critique of Kraepelins concept

was not the only one raised; another was made on

psychopathological grounds: no specificity of any

symptom of dementia praecox could be found,

whereas complexes of symptoms came close to the

target (Birnbaum, 1928). Furthermore, the work of

Bonhoeffer (1912), which had shown that one and the

same physical disease could result in totally different

psychopathological syndromes, raised serious doubts

about a purely clinical classification. The conflict

between etiological classification and syndromal psychiatric nosology was born.

Another basic assumption, that schizophrenia ends

in dementia and that manic depressive disorders

recover, also turned out to be wrong, which meant

that outcome as a validator had to be questioned. As

early as 1909, within Kraepelins school itself, Zendig

(1909) carried out a follow-up study of 468 cases of

dementia praecox diagnosed in Kraepelins clinic in

Munich. He found a favourable outcome in 29.8% of

the cases, a fact which he ascribed to misdiagnosis.

This interpretation was disproved by Langes investigation of some of the cases (Lange, 1922, p. 4). This

early finding, true but misinterpreted, namely that

dementia praecox can recover, is consistent with the

modern studies on the course and outcome of schizophrenia by Huber et al. (1979), Ciompi and Muller

(1976), Bleuler (1972) and Marneros et al. (1991),

Moller et al. (1982). Recovery cannot be explained

merely as a result of the inclusion of schizo-affective

disorders in schizophrenia; it is also true for acute

catatonia and other acute schizophrenic psychoses.

10

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

On the other hand, affective disorders should

recover and frequently do not, as already observed

by Bumke (190963240). It is a well-established

fact that 15 or more percent of cases end in chronicity and that another substantial proportion develops

residual affective symptoms between episodes. It is

more the quality of the residual states, which differ

between affective disorders and schizophrenia than

their presence or absence and the same applies to

cases which become chronic. It is not surprising that

Kurt Schneider, a strong believer in the dichotomy,

ceased to base the diagnosis of schizophrenia on

course or outcome but considered solely the presence

of first-rank symptoms. All studies of course and

outcome have demonstrated that schizo-affective

disorders lie midway between affective disorders

and schizophrenia (Kendell and Brockington, 1980;

Angst, 1986; Gross et al., 1986; Marneros et al.,

1991).

Another issue is the psychopathological continuity

from affective to schizophrenic syndromes as established by Kendell and Gourlay (1970), Kick, 1981,

Angst et al. (1981, 1983), Angst (1986) and Yasamy

(1987), findings which are concordant with Janzariks (1969) unitarian psychopathological view on a

clinical descriptive level. Mundt (1995) demonstrated

in his presentation on the psychotic continuum or

distinct entities from a psychopathological point of

view, based on the literature, that in terms of single

symptoms there is overwhelming evidence for the

diagnostic unspecificity of overall symptoms and

outcome, first-rank symptoms of Schneider, basic

symptoms of Huber (1966), negative symptoms of

Andreasen and Olsen (1982), thought disorder of

Chapman (1966) and of the psychophysiological

orientation reaction of Heimann (1986). Mundt concludes that on the single symptom level, no specificity for schizophrenia and thus no single disease

entity can be found within the spectrum of the

idiopathic psychosis.

A continuum from a genetic point of view was

postulated by Angst and Scharfetter (1985) and

Crow (1986, 1990) in contrast to the multiple threshold model of Reich et al. (1975), as discussed in

detail by Maier (1992). The genetic findings of

Gershon et al. (1982, 1988) and Maier et al.

(1993) do not disprove the hypothesis of a continuum (Crow, 1990).

7. The way forward

In the future, some progress may be achieved

through the more recent distinction between unipolar

depressive and bipolar affective and schizo-affective

disorders. It has not only been shown that, in course

and outcome, schizo-bipolar disorders (Cadoret et al.,

1974) lie between affective and schizophrenic psychoses but also that schizo-depressive psychoses are

very similar to unipolar depression and bipolar schizoaffective disorders(?) very similar to bipolar disorders.

This fact is taken into account by the inclusion of

mood-incongruent psychotic features of bipolar

manic depressive or depressive disorders in DSM.

Recently, Maier (1992) has postulated the need for an

at least two-dimensional model for a continuum from

unipolar or bipolar affective to schizophrenic disorders. It may be worthwhile to study the whole

spectrum of idiopathic psychoses from this point of

view, because our earlier cluster analyses (Angst et al.,

1983) were unable to identify a schizophrenic symptom cluster without any depression or mania. We

therefore advanced the hypothesis that affective components could be basic and common to all endogenous psychoses.

In 1995, Crow summarised: Perhaps we should

grasp the nettle and conclude that the conditions we

are concerned with are indeed continuous. There are

no defining features such as would be necessary

to establish the existence of discrete diagnostic

entities. . . But if there are no true disease entities,

there is no basis for isolating one part of the pathological spectrumthe whole range must be considered. . . and postulated that there are no disease

entities but the psychoses can be regarded as boundary conditions of continuous variation that is present

in the general population.

Over the years, the dichotomy has repeatedly been

declared dead and buried, but it has survived and may

even have a long future on a purely descriptive

syndromal level.

References

Andreasen, N.C., Olsen, S., 1982. Negative vs. positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 789

794.

tiologie und Nosologie endogener depressiver

Angst, J., 1966. Zur A

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

Psychosen. Eine Genetische, Soziologische und Klinische Studie. (Monographien aus dem Gesamtgebiete der Neurologie und

Psychiatrie 112). Springer, Berlin, pp. 1 118.

Angst, J., 1986. The course of schizoaffective disorders. In: Marneros, A., Tsuang, M.T. (Eds.), Schizoaffective Psychoses.

Springer, Berlin, pp. 63 93.

Angst, J., Scharfetter, C., 1985. Familial aspects of schizoaffective

disorder. Affective disorders. The World Psychiatric Association

Regional Symposium, Athens 1985. Abstracts S 104, 39.

Angst, J., Scharfetter, C., Stassen, H.H., 1981. Syndromwechsel und

Remission schizophrener Psychosen. In: Huber, G. (Ed.), Schizophrenie-Stand und Entwicklungstendenzen der Forschung: 4.

Weissenauer Schizophrenie-Symposion, Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1980. Schattauer, Stuttgart, pp. 117 133.

Angst, J., Scharfetter, C., Stassen, H.H., 1983. Classification of

schizo-affective patients by multidimensional scaling and cluster-analysis. In: Gabriel, E. (Ed.), Problems of Schizo-Affective

Psychoses. Symposium of the World Psychiatric Association,

Section of Clinical Psychopathology, Vienna 1982. Psychiatria

Clinica, vol. 16. Karger, Basel, pp. 254 264.

Berrios, G.E., Beer, D., 1992. Unitary psychosis in English speaking psychiatry: a conceptual history. In: Mundt, C., Sass, H.

(Eds.), Fur und Wider die Einheitspsychose. Georg Thieme,

Stuttgart, pp. 12 21.

Berrios, G.E., Beer, D., 1994. The notion of unitary psychosis: a

conceptual history. Hist. Psychiatr. 5, 13 36.

Birnbaum, K., 1928. Zur Revision der psychiatrischen Krankheitsaufstellungen. Bonhoeffer Festschr. Monatsschr. Psychiatr.

Neurol. 68, 80 101.

Bleuler, E., 1922. Die Probleme der Schizoidie und der Syntonie. Z.

Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 78, 373 399.

Bleuler, M., 1972. Die schizophrenen Geistesstorungen im Lichte

langjahriger Kranken-und Familiengeschichten. Thieme, Stuttgart.

Bonhoeffer, K., 1912. Die Psychosen im Gefolge von akuten Infektionen, Allgemeinerkrankungen und inneren E. Erkrankungen. In: Aschaffenburg, G. (Ed.), Handbuch der Psychiatrie,

Spezieller Teil, 3. Abteilung, 1. Halfte. Franz Deuticke, Leipzig,

pp. 1 118.

Brockington, I.F., Leff, J.P., 1979. Schizo-affective psychosis: definitions and incidence. Psychol. Med. 9, 91 99.

ber die Umgrenzung manisch-depressiven IrreBumke, O., 1909. U

seins. Zentralbl. Nervenheilkd. Psychiatr, N.F. 20, 381 403.

ber die gegenwartigen Stromungen in der KliBumke, O., 1924. U

nischen Psychiatrie. Munch. Med. Wochenschr., Nr. 46, 1595

1599.

Bumke, O., 1925. 50 Jahre Psychiatrie. Munch. Med. Wochenschr.

Nr. 28, 1141 1143.

Cadoret, R., Fowler, R.C., McCabe, M.S., et al., 1974. Evidence for

heterogeneity in a group of good-prognosis schizophrenics.

Compr. Psychiatry 15, 443 450.

Chapman, J., 1966. The early symptoms of schizophrenia. Br. J.

Psychiatry 112, 225 251.

Ciompi, L., Muller, C., 1976. Lebensweg und Alter der Schizophrenen. Eine Katamnestische Langzeitstudie bis ins Senium.

(Monographien aus dem Gesamtgebiete der Psychiatrie 12).

Springer, Berlin, pp. 1 242.

11

Crow, T.J., 1986. The continuum of psychosis and its implication

for the structure of the gene. Br. J. Psychiatry 149, 419 429.

Crow, T.J., 1990. The continuum of psychosis and its genetic origins: the sixty-fifth Maudsley lecture. Br. J. Psychiatry 156,

788 797.

Crow, T.J., 1995. Psychotic continuum or disease entities? The

critical impact of nosology on the problem of aetiology. In:

Marneros, A., Andreasen, N.C., Tsuang, M.T. (Eds.), Psychotic

Continuum. Springer, Berlin, pp. 151 163.

Esquirol, J.E.D., 1838. Des Maladies Mentales Considerees Sous

les Rapports Medical, Hygienique et Medico-Legal, vol. II. JB

Baillie`re, Paris.

Ey, H., 1963. La Conscience. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

Falret, J.P., 1851. Marche de la folie. Gaz. Hop. 24, 18 19.

ber Classification der Seelenstorungen nebst

Flemming, C.F., 1844. U

einem neuen Versuche derselben mit besonderer Rucksicht auf

gerichtliche Psychologie. Allg. Z. Psychiatr. 1, 97 130.

Foulds, G.A., Bedford, A., 1975. Hierarchy of classes of psychiatric

illness. Psychol. Med. 5, 181 192.

Gaupp, R., 1939. Die Lehren Kraepelins in ihrer Bedeutung fur die

heutige Psychiatrie. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 165, 47 75.

Gaupp, R., Mauz, F., 1926. Krankheitseinheit und Mischpsychose.

Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 101, 1 44.

Gershon, E.S., Hamovit, J., Guroff, J.I., et al., 1982. A family study

of schizo-affective, bipolar I, bipolar II, unipolar and normal

control probands. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 1157 1167.

Gershon, E.S., De Lisi, L.E., Hamovit, J., et al., 1988. A controlled

family study of chronic psychoses, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 45, 328 336.

Griesinger, W., 1845. Pathologie und Therapie der psychischen

rzte und Studierende, 1st edn. A Krabbe,

Krankheiten fur A

Stuttgart.

Gross, G., Huber, G., Armbruster, B., 1986. Schizoaffective psychoseslong-term prognosis and symptomatology. In: Marneros, A., Tsuang, M.T. (Eds.), Schizo-Affective Psychoses.

Springer, Berlin, pp. 188 203.

Guislain, J., 1833. Traite Des Phrenopathies ou Doctrine Nouvelle

des Maladies Mentales Etablissement Encyclopedique, Brussels.

Haustgen, T., 1993. Jean-Pierre Falret ou les debuts de la clinique

psychiatrique moderne. Synapse 95.

Heimann, H., 1986. Spezifitat und Unspezifitat bei psychischen

Erkrankungen. Schweiz. Arch. Neurol. Neurochir. Psychiatr.

137, 67 86.

Hecker, E., 1871. Die Hebephrenie. Ein Beitrag zur klinischen

Psychiatrie. Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. Klin. Med. 52,

394 429.

Hoche, P., 1912. Die Bedeutung der Symptomenkomplexe in der

Psychiatrie. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 12, 540 551.

Hoffmann, H., 1925. Grundsatzliches zur psychiatrischen Konstitutions-und Erblichkeitsforschung. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr.

97, 541 556.

Huber, G., 1966. Reine Defektsyndrome und Basisstadien endogener Psychosen. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 34, 409 426.

Huber, G., Gross, G., Schuttler, R., 1979. Schizophrene Verlaufsund Sozial-Psychiatrische Langzeituntersuchungen an den

1945 1959 in Bonn Hospitalisierten Schizophrenen Kranken.

Springer, Berlin.

12

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

Janzarik, W., 1968. Schizophrene Verlaufe. Eine Strukturdynamische Interpretation. Springer, Berlin.

Janzarik, W., 1969. Nosographie und Einheitspsychose. In: Huber,

G. (Ed.), Schizophrenie und Zyklothymie. Ergebnisse und Probleme. Thieme, Stuttgart, pp. 29 38.

Kahlbaum, K., 1863. Die Gruppirung der Psychischen Krankheiten

und die Eintheilung der Seelenstorungen. AW Kafemann, Danzig.

Kahlbaum, K., 1874. Die Katatonie Oder Das Spannungsirresein.

Eine Klinische Form Psychischer Krankheit. August Hirschwald, Berlin.

Kahlbaum, K., 1878. Die klinisch-diagnostischen Gesichtspunkte

der Psychopathologie. In: Volkmann, R. (Ed.), Sammlung Klinischer Vortrage in Verbindung mit Deutschen Klinikern. Innere

Medizin, vol. 2. Breitkopf & Hartel, Leipzig.

ber cyklisches Irresein. Irrenfreund 24, 145

Kahlbaum, K., 1882. U

157.

Kasanin, J., 1933. The acute schizo-affective psychoses. Am. J.

Psychiatry 13, 97 126.

Kehrer, F., Kretschmer, E., 1924. Die Veranlagung zu Seelischen

Storungen. (Monographien aus dem Gesamtgebiete der Neurologie 40), Springer, Berlin.

Kendell, R.E., Brockington, I.F., 1980. The definition of disease

entities and the relationship between schizophrenics and affective psychoses. Br. J. Psychiatry 137, 324 331.

Kendell, R.E., Gourlay, J., 1970. The clinical distinction between

psychotic and neurotic depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 117, 257

266.

Kick, H., 1981. Die Dichotomie der idiopathischen Psychosen im

Syndromprofil-vergleich der Kraepelinschen Krankheitsbeschreibungen. Nervenarzt 52, 522 524.

Kleist, K., 1953. Die Gliederung der neuropsychischen Erkrankungen. Monatsschr. Psychiatr. Neurol. 125, 526 554.

Kraepelin, E., 1882. Ueber die Einwirkung einiger medicamentoser

Stoffe auf die Dauer einfacher psychischer Vorgange. Philosophische Studien 1, Heft 3 (1982), S. 417 462 und Heft 4

(1883), S. 573 605.

Kraepelin, E., 1883. Compendium der Psychiatrie. Zum Gebrauche

rzte. Verlag von Ambr. Abel, Leipzig.

fur Studirende und A

Kraepelin, E., 1896. Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und

rzte, 5th edn. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig.

A

Kraepelin, E., 1897. Ziele und Wege der klinischen Psychiatrie

(3. Sitzung, 19.9.1996). Allg. Z. Psychiatr. 53, 840 844.

Kraepelin, E., 1899. Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und

rzte, 6th edn. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig.

A

Kraepelin, E., 1918. Hundert Jahre Psychiatrie. Z. Gesamte Neurol.

Psychiatr. 38, 161 275.

Kraepelin, E., 1920. Die Erscheinungsformen des Irreseins. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 62, 1 29.

Kretschmer, E., 1919. Gedanken uber die Fortentwicklung der psychiatrischen Systematik. Bemerkungen zu vorstehender Abhandlung. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 48, 371 377.

Kretschmer, E., 1929. Geleitwort: die Prognostik der endogenen

Psychosen. Friedrich Mauz: Psychiatrische Schriften. Sofortdruck Horst Nath, Munster, Westfahlen.

Lange, J., 1922. Katatonische Erscheinungen im Rahmen manischer

Erkrankungen. (Monographien aus dem Gesamtgebiete der

Neurologie und Psychiatrie 31), Springer, Berlin.

Leonhard, K., 1968. Aufteilung der Endogenen Psychosen, 4th edn.

Akademie Verlag, Berlin.

Maier, W., 1992. Kontinuitat und Diskontinuitat funktioneller Psychosyndrome im Lichte von Familienstudien. In: Mundt, C.,

Sass, H. (Eds.), Fur und Wider die Einheitspsychose. Georg

Thieme, New York, pp. 99 109.

Maier, W., Lichtermann, D., Minges, J., Hallmayer, J., Heun, R.,

Benkert, O., Levinson, D.F., 1993. Continuity and discontinuity

of affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry

50, 871 883.

Marneros, A., Deister, A., Rohde, A., 1991. Affektive, Schizoaffektive und Schizophrene Psychosen. Eine Vergleichende Langzeitstudie. Springer, Berlin.

Mayer-Gross, W., 1932. Die Klinik. In: Bumke, O. (Ed.), Handbuch

der Geistes-krankeiten, Band 9, spezieller Teil V: Die Schizophrenie. Springer, Berlin, pp. 293 578.

Moller, H.J., von Zerssen, D., Werner-Eilert, K., Wuschner-Stockheim, M., 1982. Outcome in schizophrenic and similar paranoid

psychoses. Schizophr. Bull. 8, 99 108.

Morel, B.A., 1851. Etudes cliniques Traite Theorique et Pratique

des Maladies Mentales. Victor Masson, Paris.

Mundt, C., 1995. Psychotic continuum or distinct entities: perspectives from psychopathology. In: Marneros, A., Andreasen, N.C.,

Tsuang, M.D. (Eds.), Psychotic Continuum. Springer, Berlin,

pp. 7 15.

Neumann, H., 1859. Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. Enke, Erlangen.

Perris, C., 1966. A study of bipolar (manic depressive) and unipolar recurrent depressive psychoses. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.,

194, 1 189 (Suppl).

Pichot, P., 1995. The birth of the bipolar disorder. Eur. Psychiatr. 10,

1 10.

Plater, F., 1625. Annales de Medicine. Praxis medica, Basel.

Reich, T.T., Cloninger, C.R., Guze, S.B., 1975. The multifactorial

model of disease transmission: I. Description of the model and

its use in psychiatry. Br. J. Psychiatry 127, 1 10.

Rennert, H., 1965. Die Universalgenese der endogenen Psychosen.

Ein Beitrag zum Problem Einheitspsychose. Fortschr. Neurol.

Psychiatr. 33, 251 272.

Roelcke, V., 1996. Die wissenschaftliche Vermessung der Geisteskrankheiten. Emil Kraepelins Lehre von den endogenen Psychosen. In: Schott, H. (Ed.), Meilensteine der Medizin.

Harenberg Verlag, Dortmund, pp. 389 395.

Roelcke, V., 1997. Biologizing social facts: an early 20th century

debate on Kraepelins concept of culture, neurasthenia, and degeneration. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 21, 383 403.

Schneider, K., 1967. Klinische Psychopathologie, 8th edn. Thieme,

Stuttgart.

Schule, H., 1878. Handbuch der Geisteskrankheiten. Vogel, Leipzig.

Smith, J.C., 1925. Atypical psychoses and heterologous hereditary

taints. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 62, 1 32.

Spitzer, R.L., Endicott, J., Robins, E., 1978. Research Diagnostic

Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders,

3rd edn. Biometrics Research New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, pp. 9 11.

J. Angst / Schizophrenia Research 57 (2002) 513

Stransky, E., 1911. Das Manisch-Depressive Irresein. Franz Deuticke, Leipzig.

Urstein, M., 1909. Die Dementia Praecox und Ihre Stellung zum

Manisch-Depressiven Irresein. Eine Klinische Studie. Urban &

Schwarzenberg, Berlin.

Vliegen, J., 1980. Die Einheitspsychose. Geschichte und Problem.

Enke, Stuttgart.

Winokur, G., Clayton, P.J., Reich, T., 1969. Manic Depressive Illness. CV Mosby, Saint Louis.

13

Yasamy, M.T., 1987. Schizoaffective disorder: a dimensional approach. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 76, 609 618.

Zeller, E., 1837. Bericht uber die Wirksamkeit der Heilanstalt Winnenthal von ihrer Eroffnung den 1. Marz 1834 bis zum 28.

rztl. Ver.

February 1837. Beil. Med. Corresp.-Bl. Wurtemb. A

7, 321 335.

Zendig, 1909. Beitrage zur Differentialdiagnose des manisch-depressiven Irreseins und der Dementia praecox. Allg. Z. Psychiatr. 66, 932 933.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Body Sculpturing Techniques: Mesotherapy, Lipodissolve and CarboxytherapyDocument104 pagesBody Sculpturing Techniques: Mesotherapy, Lipodissolve and CarboxytherapyRizky Apriliana HardiantoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Mount Sinai Obstetrics and Ginecology 2020Document414 pagesMount Sinai Obstetrics and Ginecology 2020David Bonnett100% (1)

- Case ManagementDocument4 pagesCase ManagementPraveena.R100% (1)

- DENGUE CS NCP 1Document8 pagesDENGUE CS NCP 1Karyl SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Eating DisorderDocument5 pagesEtiology of Eating DisorderCecillia Primawaty100% (1)

- Merged PDF 2021 11 16T12 - 01 - 01Document15 pagesMerged PDF 2021 11 16T12 - 01 - 01Ericsson CarabbacanNo ratings yet

- Bhavnagar DrsDocument39 pagesBhavnagar DrsCHETAN MOJIDRA75% (4)

- English for Nurses: A Concise GuideDocument137 pagesEnglish for Nurses: A Concise GuideLIDYANo ratings yet

- NetworkHospital NEW UPDATEDDocument488 pagesNetworkHospital NEW UPDATEDalina0% (1)

- Azlan Shafer - Abū Alī Al - Asan Ibn Al - Asan Ibn Al-HaythamDocument3 pagesAzlan Shafer - Abū Alī Al - Asan Ibn Al - Asan Ibn Al-HaythamFulguraNo ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized Title for Document on English Language Exam QuestionsDocument22 pagesSEO-Optimized Title for Document on English Language Exam QuestionsFulguraNo ratings yet

- Fantasy TypesDocument4 pagesFantasy TypesFulguraNo ratings yet

- Fantasy TypesDocument4 pagesFantasy TypesFulguraNo ratings yet

- Ancient and Medieval History MapsDocument135 pagesAncient and Medieval History MapsFulguraNo ratings yet

- Kemal Hulus - Unique PlaceDocument1 pageKemal Hulus - Unique PlaceFulguraNo ratings yet

- CoPiino Humidity Control Workshop Using Raspberry PiDocument7 pagesCoPiino Humidity Control Workshop Using Raspberry PiFulguraNo ratings yet

- User Manual: DV F/DV F/DV F/DV2014F/DV1506FDocument163 pagesUser Manual: DV F/DV F/DV F/DV2014F/DV1506FFulguraNo ratings yet

- Bolo BoloDocument108 pagesBolo BoloBezdomny DotcomNo ratings yet

- TP-LINK TL-MR3040 Antenna Modification GuideDocument9 pagesTP-LINK TL-MR3040 Antenna Modification GuideFulguraNo ratings yet

- Khadija Salam Ullah Ala PDFDocument37 pagesKhadija Salam Ullah Ala PDFRizwan SakhawatNo ratings yet

- UW 27 VanPutten PDFDocument53 pagesUW 27 VanPutten PDFFulguraNo ratings yet

- Language and Masculinity in Roth and MametDocument10 pagesLanguage and Masculinity in Roth and MametFulguraNo ratings yet

- 10 Report 3Document2 pages10 Report 3FulguraNo ratings yet

- 02 IordanovaDocument12 pages02 IordanovaFulguraNo ratings yet

- 10 Report 1Document2 pages10 Report 1FulguraNo ratings yet

- 04 BalditDocument13 pages04 BalditFulguraNo ratings yet

- 03 NymanDocument12 pages03 NymanFulguraNo ratings yet

- 11 ReportDocument3 pages11 ReportFulguraNo ratings yet

- 03 HaneyDocument17 pages03 HaneyFulguraNo ratings yet

- 04 DelickaDocument11 pages04 DelickaFulguraNo ratings yet

- 05 PultarDocument18 pages05 PultarFulguraNo ratings yet

- 03 VegaDocument9 pages03 VegaFulguraNo ratings yet

- 02 PatellDocument8 pages02 PatellFulguraNo ratings yet

- 10 Film ReviewDocument3 pages10 Film ReviewFulguraNo ratings yet

- 06 AlvarezDocument11 pages06 AlvarezFulguraNo ratings yet

- 06 AlvarezDocument11 pages06 AlvarezFulguraNo ratings yet

- 02 KneeDocument17 pages02 KneeFulguraNo ratings yet

- Film Reviews of Independence Day, Kids, and Things to Do in DenverDocument4 pagesFilm Reviews of Independence Day, Kids, and Things to Do in DenverFulguraNo ratings yet

- 07 GatesDocument25 pages07 GatesFulguraNo ratings yet

- Differential Diagnosis of Scalp Hair FolliculitisDocument8 pagesDifferential Diagnosis of Scalp Hair FolliculitisandreinaviconNo ratings yet

- Arthritis Fact SheetDocument2 pagesArthritis Fact SheetClaire MachicaNo ratings yet

- OmronDocument19 pagesOmrondekifps9893No ratings yet

- Surgery Chapter 1 SkinDocument6 pagesSurgery Chapter 1 Skinnandoooo86No ratings yet

- Elephantiasis: Report AboutDocument8 pagesElephantiasis: Report AboutAmjadRashidNo ratings yet

- Inter Disciplinary Periodontics A Multi Disciplinary Approach To Complex Case Planning and TreatmentDocument17 pagesInter Disciplinary Periodontics A Multi Disciplinary Approach To Complex Case Planning and TreatmentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Jadwal OktoberDocument48 pagesJadwal OktoberFerbian FakhmiNo ratings yet

- 2020 Collet-Sicard Syndrome After Jefferson FractureDocument3 pages2020 Collet-Sicard Syndrome After Jefferson FractureJose ColinaNo ratings yet

- Abses Perianal JurnalDocument4 pagesAbses Perianal JurnalAnonymous tDKku2No ratings yet

- IU Vaccine LawsuitDocument55 pagesIU Vaccine LawsuitJoe Hopkins100% (2)

- DR Anuj Raj BijukchheDocument60 pagesDR Anuj Raj BijukchheMUHAMMAD JAWAD HASSANNo ratings yet

- Caring Adoption Associates: Medical Examination Report of Prospective Adoptive ParentDocument1 pageCaring Adoption Associates: Medical Examination Report of Prospective Adoptive ParentaniketsethiNo ratings yet

- Types and Causes of Phobias ExplainedDocument24 pagesTypes and Causes of Phobias ExplainedDebjyoti BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Diabetic FootDocument11 pagesDiabetic Footmuhhasanalbolkiah saidNo ratings yet

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease - Causes, Diagnosis, Cardiometabolic Consequences, and Treatment StrategiesDocument12 pagesNon-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease - Causes, Diagnosis, Cardiometabolic Consequences, and Treatment StrategiesntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- 12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudyDocument6 pages12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudymailcdgnNo ratings yet

- IMMUNOLOGY COURSE MODULE ON IMMUNOGLOBULINSDocument8 pagesIMMUNOLOGY COURSE MODULE ON IMMUNOGLOBULINSboatcomNo ratings yet

- PTJ 99 12 1587Document15 pagesPTJ 99 12 1587ganesh goreNo ratings yet

- Year 3 Undergraduate Progressive Test - Attempt reviewPDF - 231031 - 194511Document49 pagesYear 3 Undergraduate Progressive Test - Attempt reviewPDF - 231031 - 194511DR BUYINZA TITUSNo ratings yet

- AIJ Clasif PRINTO 2019Document9 pagesAIJ Clasif PRINTO 2019Michael ParksNo ratings yet

- Physical Exam of the Eye: Structures, Findings, DiagnosesDocument16 pagesPhysical Exam of the Eye: Structures, Findings, DiagnosesriveliNo ratings yet