Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unit 2

Uploaded by

api-259253396Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unit 2

Uploaded by

api-259253396Copyright:

Available Formats

UNIT II: 600 - 1450 C.E.

This second era is much shorter than the previous one, but during the years between 600 and 1450 C.E. many earlier

trends continued to be reinorced, while some very important new patterns emerged that shaped all subse!uent times.

QUESTIONS OF PERIODIZATION

Change over time occurs or many reasons, but three phenomena that tend to cause it are"

#ass migrations $ %henever a signiicant number o people leave one area and migrate to another, change occurs

or both the land that they let as well as their destination

&mperial con!uests $ & an empire 'or later a country( deliberately con!uers territory outside its borders, signiicant

changes tend to ollow or both the attac)ers and the attac)ed.

Cross$cultural trade and e*change $ %idespread contact among various areas o the world brings not only new

goods but new ideas and customs to all areas involved.

+uring the classical era 'about 1000 ,CE to 600 CE(, all o these phenomena occurred, as we saw in -nit &. %ith the all

o the three ma.or classical civili/ations, the stage was set or new trends that deined 600$1450 CE as another period with

dierent migrations and con!uests, and more developed trade patterns than beore. 0ome ma.or events and developments

that characteri/ed this era were"

1lder belie systems, such as Christianity, 2induism, Conucianism, and ,uddhism, came to become more

important than political organi/ations in deining many areas o the world. 3arge religions covered huge areas o

land, even though locali/ed smaller religions remained in place.

Two nomadic groups $ the ,edouins and the #ongols $ had a huge impact on the course o history during this era.

4 new religion $ &slam $ began in the 5th century and spread rapidly throughout the #iddle East, 6orthern

4rica, Europe, and 0outheast 4sia.

%hereas Europe was not a ma.or civili/ation area beore 600 CE, by 1450 it was connected to ma.or trade routes,

and some o its )ingdoms were beginning to assert world power.

#a.or empires developed in both 0outh 4merica 'the &nca( and #esoamerica 'the #aya and 4/tec.(

China grew to have hegemony over many other areas o 4sia and became one o the largest and most prosperous

empires o the time.

3ong distance trade continued to develop along previous routes, but the amount and comple*ity o trade and

contact increased signiicantly.

This unit will investigate these ma.or shits and continuities by addressing several broad topics"

The &slamic %orld $ &slam began in the 4rabian 7eninsula in the 5th century CE, impacting political and

economic structures, and shaping the development o arts, sciences and technology.

&nterregional networ)s and contacts $ 0hits in and e*pansion o trade and cultural e*change increase the power

o China, connected Europe to other areas, and helped to spread the ma.or religions. The #ongols irst disrupted

then promoted long$distance trade throughout 4sia, 4rica, and Europe.

China8s internal and e*ternal e*pansion $ +uring the Tang and 0ong +ynasties, China e*perienced an economic

revolution and e*panded its inluence on surrounding areas. This era also saw China ta)en over by a powerul

nomadic group 'the #ongols(, and then returned to 2an Chinese under the #ing +ynasty.

+evelopments in Europe $ European )ingdoms grew rom nomadic tribes that invaded the 9oman Empire in the

5th century C.E. +uring this era, eudalism developed, and Christianity divided in two $ the Catholic Church in

the west and the Eastern 1rthodo* Church in the east. &n both cases, the Church grew to have a great deal o

political and economic power.

0ocial, cultural, economic patterns in the 4merindian world $ #a.or civili/ations emerged, building on the base o

smaller, less powerul groups rom the previous era. The #aya, 4/tec, and &nca all came to control large amounts

o territory and many other native groups.

+emographic and environmental changes $ -rbani/ation continued, and ma.or cities emerged in many parts o the

world. 6omadic migrations during the era included the 4/tecs, #ongols, Tur)s, :i)ings, and 4rabs. 3ong

distance trade promoted the spread o disease, including the plague pandemics in the early ourteenth century.

THE CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS (1000 BCE - 600 CE)

The period ater the decline o river valley civili/ations 'about 1000 ,CE $ 600 CE( is oten called the classical age.

+uring this era world history was shaped by the rise o several large civili/ations that grew rom areas where the earlier

civili/ations thrived. The classical civili/ations dier rom any previous ones in these ways"

1. They )ept better and more recent records, so historical inormation about them is much more abundant. %e )now more

about not .ust their wars and their leaders, but also about how ordinary people lived.

;. The classical societies provide many direct lin)s to today8s world, so that we may reer to them as root civili/ations, or

ones that modern societies have grown rom.

<. Classical civili/ations were e*pansionist, deliberately con!uering lands around them to create large empires. 4s a result,

they were much larger in land space and population than the river civili/ations were.

Three areas where civili/ations proved to be very durable were

The #editerranean $ Two great classical civili/ations grew up around this area" the =ree)s and the 9omans.

China $ The classical era began with the >hou Empire and continued through the 2an +ynasty.

&ndia $ 4lthough political unity was diicult or &ndia, the #auryan and =upta Empire emerged during the

classical era.

COMMON FEATURES OF CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS

The three areas o classical civili/ations developed their own belies, liestyles, political institutions, and social structures.

2owever, there were important similarities among them"

7atriarchal amily structures $ 3i)e the river valley civili/ations that preceded them, the classical civili/ation

valued male authority within amilies, as well as in most other areas o lie.

4gricultural$based economies $ +espite more sophisticated and comple* .ob speciali/ation, the most common

occupation in all areas was arming.

Comple* governments $ ,ecause they were so large, these three civili/ations had to invent new ways to )eep their

lands together politically. Their governments were large and comple*, although they each had uni!ue ways o

governing

E*panding trade base $ Their economic systems were comple*. 4lthough they generally operated independently,

trade routes connected them by both land and sea.

CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS

C!"#$ P%!&"&'(! O#)(*&+("&%* S%'&(! S"#'"#$

,#$$'$ ((-%"

.00-/00 BCE)

#ost enduring inluences come rom

4thens"

:alued education, placed emphasis on

importance o human eort, human ability

to shape uture events

&nterest in political theory" which orm o

government is best?

Celebration o human individual

achievement and the ideal human orm

7hilosophy and science emphasi/ed the use

o logic

2ighly developed orm o sculpture,

literature, math, written language, and

record )eeping

7olytheism, with gods having very human

characteristics

6o centrali/ed government@

concept o polis, or a ortiied

site that ormed the centers o

many city states

=overning styles varied '0parta

a military state, 4thens

eventually a democracy or adult

males(

4thens government irst

dominated by tyrants, or strong

rulers who gained power rom

military prowess@ later came to

be ruled by an assembly o ree

men who made political

decisions.

,oth 4thens and 0parta

developed strong military

organi/ations and established

colonies around the

#editerranean. 0parta

0lavery widely practiced

#en separated rom women

in military barrac)s until age

<0@ women had relative

reedom@ women in 0parta

encouraged to be physically

it so as to have healthy

babies@ generally better

treated and more e!ual to

men than women in 4thens

4thens encouraged e!uality

or ree males, but women

and slaves had little reedom.

6either group allowed to

participate in polis aairs.

0ocial status dependent on

land holdings and cultural

sophistication

Cities relatively small

=reat seaaring s)ills, centered around

4egean, but traveling around entire

#editerranean area

theoretically e!ual@ wealth

accumulation not allowed

R%0$ ((-%"

500 BCE "% 416

CE2 (!"3%)3

$(4"$#* 3(!5

'%*"&*$6 5%#

(*%"3$#

"3%4(*6

7$(#4)

7erection o military techni!ues" con!uer

but don8t oppress@ division o army into

legions, emphasi/ing organi/ation and

rewarding military talent

4rt, literature, philosophy, science

derivative rom =reece

0uperb engineering and architecture

techni!ues@ e*tensive road, sanitation

systems@ monumental architecture

$buildings, a!ueducts, bridges

7olytheism, derivative rom =ree)s, but

religion not particularly important to the

average 9oman@ Christianity developed

during Empire period, but not dominant

until very late

=reat city o 9ome $ buildings, arenas,

design copied in smaller cities

Two eras"

9epublic $ rule by aristocrats,

with some power shared with

assemblies@ 0enate most

powerul, with two consuls

chosen to rule, generally

selected rom the military

Empire $ non$hereditary

emperor@ technically chosen by

0enate, but generally chosen by

predecessor

E*tensive coloni/ation and

military con!uest during both

eras

+evelopment o an overarching

set o laws, restrictions that all

had to obey@ 9oman law sets in

place principle o rule o law,

not rule by whim o the political

leader

,asic division between

patricians 'aristocrats( and

plebeians 'ree armers(,

although a middle class o

merchants grew during the

empire@ wealth based on land

ownership@ gap between rich

and poor grew with time

7ateramilias $ male

dominated amily structure

7atron$client system with

rich supervising elaborate

webs o people that owe

avors to them

&ne!uality increased during

the empire, with great

dependence on slavery

during the late empire@

slaves used in households,

mines, large estates, all )inds

o manual labor

C3&*( ((-%"

500 BCE "% 600

CE)

Conucianism developed during late >hou@

by 2an times, it dominated the political and

social structure.

3egalism and +aoism develop during same

era.

,uddhism appears, but not inluential yet

Threats rom nomads rom the south and

west spar) the irst construction o the

=reat %all@ clay soldiers, lavish tomb or

irst emperor 0hi 2uangdi

Chinese identity cemented during 2an era"

the A2anA Chinese

2an $ a Agolden ageA with prosperity rom

trade along the 0il) 9oad@ inventions

include water mills, paper, compasses, and

pottery and sil)$ma)ing@ calendar with

>hou $ emperor rules by

mandate o heaven, or belie that

dynasties rise and all according

to the will o heaven, or the

ancestors. Emperor was the Ason

o heaven.A

Emperor housed in the orbidden

city, separate rom all others

7olitical authority controlled by

Conucian values, with emperor

in ull control but bound by duty

7olitical power centrali/ed

under 0hi 2uangdi $ oten seen

Bamily basic unit o society,

with loyalty and obedience

stressed

%ealth generally based on

land ownership@ emergence

o scholar gentry

=rowth o a large merchant

class, but merchants

generally lower status than

scholar$bureaucrats

,ig social divide between

rural and urban, with most

wealth concentrated in cities

0ome slavery, but not as

much as in 9ome

7atriarchal society

<65.5 days

Capital o Ci8an possibly the most

sophisticated, diverse city in the world at

the time@ many other large cities

as the irst real emperor

2an $ strong centrali/ed

government, supported by the

educated shi 'scholar

bureaucrats who obtained

positions through civil service

e*ams(

reinorced by Conucian

values that emphasi/ed

obedience o wie to

husband

I*6&(

4ryan religious stories written down into

:edas, and 2induism became the dominant

religion, although ,uddhism began in &ndia

during this era@

#auryans ,uddhist, =uptas 2indu

=reat epic literature such as the 9amayana

and #ahabarata

E*tensive trade routes within subcontinent

and with others@ connections to 0il) 9oad,

and heart o &ndian 1cean trade@ coined

money or trade

0o$called 4rabic numerals developed in

&ndia, employing a 10$based system

3ac) o political unity $

geographic barriers and diversity

o people@ tended to ragment

into small )ingdoms@

political authority less important

than caste membership and

group allegiances

#auryan and =upta Empires

ormed based on military

con!uest@ #auryan

Emperor 4sho)a seen as

greatest@ converted to ,uddhism,

)ept the religion alive

Atheater stateA techni!ues used

during =upta $ grand palace and

court to impress all visitors,

conceal political wea)ness

Comple* social hierarchy

based on caste membership

'birth groups called .ati(@

occupations strictly dictated

by caste

Earlier part o time period $

women had property rights

+ecline in the status o

women during =upta,

corresponding to increased

emphasis on ac!uisition and

inheritance o property@

ritual o sati or wealthy

women ' widow cremates

hersel in her husband8s

uneral pyre(

,LOBAL TRADE AND CONTACT

+uring the classical era the ma.or civili/ations were not entirely isolated rom one another. #igrations continued, and

trade increased, diusing technologies, ideas, and goods rom civili/ation centers to more parts o the world. 2owever,

the process was slow. Chinese inventions such as paper had not yet reached societies outside East 4sia by the end o the

classical era. The %estern 2emisphere was not yet in contact with the Eastern 2emisphere. 6evertheless, a great deal o

cultural diusion did ta)e place, and larger areas o the world were in contact with one another than in previous eras.

1ne very important e*ample o cultural diusion was 2elleni/ation, or the deliberate spread o =ree) culture. The most

important agent or this important change was 4le*ander the =reat, who con!uered Egypt, the #iddle East, and the large

empire o 7ersia that spread eastward all the way to the &ndus 9iver :alley. 4le*ander was #acedonian, but he controlled

=reece and was a big an o =ree) culture. 2is con!uests meant that =ree) architecture, philosophy, science, sculpture,

and values diused to large areas o the world and greatly increased the importance o Classical =reece as a root culture.

Trade routes that lin)ed the classical civili/ations include"

T3$ S&!8 R%(6 $ This overland route e*tended rom western China, across Central 4sia, and inally to the

#editerranean area. Chinese sil) was the most desired commodity, but the Chinese were willing to trade it or

other goods, particularly or horses rom Central 4sia. There was no single route, but it consisted o a series o

passages with common stops along the way. #a.or trade towns appeared along the way where goods were

e*changed. 6o single merchant traveled the entire length o the road, but some products 'particularly sil)( did

ma)e it rom one end to the other.

T3$ I*6&(* O'$(* T#(6$ $ This important set o water routes became even more important in later eras, but the

&ndian 1cean Trade was actively in place during the classical era. The trade had three legs" one connected eastern

4rica and the #iddle East with &ndia@ another connected &ndia to 0outheast 4sia@ and the inal one lin)ed

0outheast 4sia to the Chinese port o Canton.

S(3(#(* T#(6$ $ This route connected people that lived south o the 0ahara to the #editerranean and the #iddle

East. The ,erbers, nomads who traversed the desert, were the most important agents o trade. They carried goods

in camel caravans, with Cairo at the mouth o the 6ile 9iver as the most important destination. There they

connected to other trade routes, so that Cairo became a ma.or trade center that lin)ed many civili/ations together.

S--S(3(#(* T#(6$ $ This trade was probably inspired by the ,antu migration, and by the end o the classical

era people south o the 0ahara were connect to people in the eastern and southern parts o 4rica. This trade

connected to the &ndian 1cean trade along the eastern coast o 4rica, which in turn connected the people o sub$

0aharan 4rica to trade centers in Cairo and &ndia.

TRADE DURIN, THE CLASSICAL ERA (1000 BCE "% 600 CE)

9oute +escription %hat traded? %ho participated? Cultural diusion

0il) 9oad

1verland rom western China to

the #editerranean Trade made

possible by development o a

camel hybrid capable o long

dry trips

Brom west to east $

horses, alala,

grapes, melons,

walnuts

Brom east to west $

sil), peaches,

apricots, spices,

pottery, paper

Chinese, &ndians,

7arthians, central

4sians, 9omans

7rimary agents o trade

$ central 4sian nomads

Chariot warare, the stirrup, music,

diversity o populations, ,uddhism

and Christianity, wealth and

prosperity 'particularly important

or central 4sian nomads(

&ndian

1cean

Trade

,y water rom Canton in China

to 0outheast 4sia to &ndia to

eastern 4rica and the #iddle

East@ monsoon$controlled

7igments, pearls,

spices, bananas and

other tropical ruits

Chinese, &ndians,

#alays, 7ersians,

4rabs, people on

4rica8s east coast

3ateen sail 'lattened triangular

shape( permitted sailing ar rom

coast

Created a trading class with

mi*ture o cultures, ties to

homeland bro)en

0aharan

Trade

7oints in western 4rica south

o the 0ahara to the

#editerranean@ Cairo most

important destination

Camel caravans

0alt rom 0ahara to

points south and west

=old rom western

4rica

%heat and olives

rom &taly

9oman manuactured

goods to western

4rica

%estern 4ricans,

people o the

#editerranean

,erbers most

important agents o

trade

Technology o the camel saddle $

important because it allowed

domestication and use o the camel

or trade

0ub$

0aharan

Trade

Connected 4ricans south and

east o the 0ahara to one

another@ connected in the east to

other trade routes

4gricultural

products, iron

weapons

+iverse peoples in

sub$0aharan 4rica

,antu language, A4ricanityA

THE LATE CLASSICAL ERA: THE FALL OF EMPIRES (900 TO 600 CE)

9ecall that all o the river$valley civili/ation areas e*perienced signiicant decline andDor con!uest in the time period

around 1;00 ,CE. 4 similar thing happened to the classical civili/ations between about ;00 and 600 CE, and because the

empires were larger and more connected, their all had an even more signiicant impact on the course o world history.

2an China was the irst to all 'around ;;0 CE(, then the %estern 9oman Empire '456 CE(, and inally the =upta in 550

CE.

SIMILARITIES

0everal common actors caused all three empires to all"

4ttac)s rom the 2uns $ The 2uns were a nomadic people o 4sia that began to migrate south and west during

this time period. Their migration was probably caused by drought and lac) o pasture, and the invention and use

o the stirrup acilitated their attac)s on all three established civili/ations.

+eterioration o political institutions $ 4ll three empires were riddled by political corruption during their latter

days, and all three suered under wea)$willed rulers. #oral decay also characteri/ed the years prior to their

respective alls.

7rotectionDmaintenance o borders $ 4ll empires ound that their borders had grown so large that their military had

trouble guarding them. 4 primary e*ample is the ailure o the =reat %all to )eep the 2uns out o China. The

2uns generally .ust went around it.

+iseases that ollowed the trade routes $ 7lagues and epidemics may have )illed o as much as hal o the

population o each empire.

DIFFERENCES

Even though the empires shared common reasons or their declines, some signiicant dierences also may be seen.

The =upta8s dependence on alliances with regional princes bro)e down, e*hibiting the tendency toward political

ragmentation on the &ndian subcontinent.

9ome8s empire lasted much longer than did either o the other two. The 9oman Empire also split in two, and the

eastern hal endured or another 1000 years ater the west ell.

The all o empire aected the three areas in dierent ways. The all o the =upta probably had the least impact,

partly because political unity wasn8t the rule anyway, and partly because the traditions o 2induism and the caste

system 'the glue that held the area together( continued on ater the empire ell. The all o the 2an +ynasty was

problematic or China because strong centrali/ed government was in place, and social disorder resulted rom the

loss o authority. 2owever, dynastic cycles that ollowed the dictates o the #andate o 2eaven were well deined

in China, and the Conucian traditions continued to give coherence to Chinese society. The most devastating all

o all occurred in 9ome. 9oman civili/ation depended almost e*clusively on the ability o the government and the

military to control territory. Even though Christianity emerged as a ma.or religion, it appeared so late in the lie o

the empire that it provided little to uniy people as 9omans ater the empire ell. &nstead, the areas o the empire

ragmented into small parts and developed uni!ue characteristics, and the %estern 9oman Empire never united

again.

COMMON CONSEQUENCES

The all o the three empires had some important conse!uences that represent ma.or turning points in world history"

Trade was disrupted but survived, )eeping intact the trend toward increased long$distance contact. Trade on the

&ndian 1cean even increased as conlict and decline o political authority aected overland trade.

The importance o religion increased as political authority decreased. &n the west religion, particularly Christianity

was let to slowly develop authority in many areas o people8s lives. ,uddhism also spread !uic)ly into China,

presenting itsel as competition to Conucian traditions.

7olitical disunity in the #iddle East orged the way or the appearance o a new religion in the 5th century. ,y

600 CE &slam was in the wings waiting to ma)e its entrance onto the world stage.

BELIEF S:STEMS

,elie systems include both religions and philosophies that help to e*plain basic !uestions o human e*istence, such as

A%here did we come rom?A 1r A%hat happens ater death?A or A%hat is the nature o human relationships or

interactions?A #any ma.or belies systems that inluence the modern world began during the Boundations Era 'E000 ,CE

to 600 CE(.

713FT2E&0#

The earliest orm o religion was probably polydaemonism 'the belie in many spirits(, but somewhere in the 6eolithic era

people began to put these spirits together to orm gods. &n polytheism, each god typically has responsibility or one area o

lie, li)e war, the sea, or death. &n early agricultural societies, !uite logically most o the gods had responsibility or the

raising o crops and domesticated animals. The most prominent god in many early societies was the 0un =od, who too)

many orms and went by many names. 1ther gods supervised rain, wind, the moon, or stars. #any societies worshipped

gods o ertility, as relected in statues o pregnant goddesses, or women with e*aggerated emale eatures. Foung male

gods oten had eatures or bulls, goats, or .aguars that represented power, energy, andDor virility. 7erceptions o the gods

varied rom one civili/ation to the ne*t, with some seeing them as ierce and ull o retribution, and others seeing them as

more tolerant o human oibles.

9eligion was e*tremely important to the river$valley civili/ations, and most areas o lie revolved around pleasing the

gods. #onotheism was irst introduced about ;000 ,CE by &sraelites, but monotheism did not grow substantially till

much later. Each o the classical civili/ations had very dierent belie systems that partially account or the very dierent

directions that the three areas too) in succeeding eras. 9ome and =reece were polytheistic, but Christianity had a irm

ooting by the time the western empire ell. 2induism dominated &ndian society rom very early times, although

,uddhism also too) root in &ndia. Brom China8s early days, ancestors were revered, a belie reinorced by the philosophy

o Conucianism. 1ther belie systems, such as +aoism, 3egalism, and ,uddhism, also lourished in China by 600 CE.

2&6+-&0#

The beginnings o 2induism are diicult to trace, but the religion originated with the polytheism that the 4ryans brought

as they began invading the &ndian subcontinent sometime ater ;000 ,CE. 4ryan priest recited hymns that told stories and

taught values and were eventually written down in The :edas, the sacred te*ts o 2induism. 1ne amous story is The

9amayana that tells about the lie and love o 7rince 9ama and his wie 0ita. 4nother epic story is The #ahabharata,

which ocuses on a war between cousins. &ts most amous part is called The ,aghavad =ita, which tells how one

cousin, 4r.una, overcomes his hesitations to ight his own )in. The stories embody important 2indu values that still guide

modern day &ndia.

2induism assumes the eternal e*istence o a universal spirit that guides all lie on earth. 4 piece o the spirit called the

atman is trapped inside humans and other living creatures. The most important desire o the atman is to be reunited with

the universal spirit, and every aspect o an individual8s lie is governed by it. %hen someone dies, their atman may be

reunited, but most usually is reborn in a new body. 4 person8s caste membership is a clear indication o how close he or

she is to the desired reunion. 0ome basic tenets o 2induism are

9eincarnation $ 4tman spirits are reborn in dierent people ater one body dies. This rebirth has no beginning and

no end, and is part o the larger universal spirit that pervades all o lie.

Garma $ This widely used word actually reers to the pattern o cause and eect that transcends individual human

lives. %hether or not an individual ulills hisDher duties in one lie determines what happens in the ne*t.

+harma $ +uties called dharma are attached to each caste position. Bor e*ample, a warrior8s dharma is to ight

honorably, and a wie8s duty is to serve her husband aithully. Even the lowliest caste has dharma attached to it. &

one ulills this dharma, the reward is or the atman to be reborn into a higher caste. 1nly the atman o a member

o the highest caste 'originally the priests( has the opportunity to be reunited with the universal spirit.

#o)sha $ #o)sha is the highest, most sought$ater goal or the atman. &t describes the reunion with the universal

spirit.

The universal spirit is represented by ,rahman, a god that ta)es many dierent shapes. Two o ,rahman8s orms are

:ishnu the Creator, and 0hiva the +estroyer. 2induism is very diicult to categori/e as either polytheistic or monotheistic

because o the central belie in the universal spirit. +o each o ,rahman8s orms represent a dierent god, or are they all

the same? ,rahman8s orms almost certainly represent dierent 4ryan gods rom the religion8s early days, but 2induism

eventually unites them all in the belie in ,rahman.

,-++2&0#

,uddhism began in &ndia in the =anges 9iver are during the 6th century ,CE. &ts ounder was 0iddhartha =uatama, who

later became )nown as the ,uddha, or the AEnlightened 1ne.A 0iddhartha was the son o a wealthy 2indu prince who

grew up with many advantages in lie. 2owever, as a young man he did not ind answers to the meaning o lie in

2induism, so he let home to become an ascetic, or wandering holy man. 2is Enlightenment came while sitting under a

tree in a +eerield, and the revelations o that day orm the basic tenets o ,uddhism"

T3$ F%# N%-!$ T#"34 $ 1( 4ll o lie is suering@ ;( 0uering is caused by alse desires or things that do not

bring satisaction@ <( 0uering may be relieved by removing the desire@ 4( +esire may be removed by ollowing

the Eightold 7ath.

T3$ E&)3"5%!6 P("3 "% E*!&)3"$*0$*" $ The ultimate goal is to ollow the path to nirvana, or a state o

contentment that occurs when the individual8s soul unites with the universal spirit. The eight steps must be

achieved one by one, starting with a change in thoughts and intentions, ollowed by changes in lie style and

actions that prelude a higher thought process through meditation. Eventually, a Abrea)throughA occurs when

nirvana is achieved that gives the person a whole new understanding o lie.

6ote that 2induism supported the continuation o the caste system in &ndia, since castes were an outer relection o inner

purity. Bor e*ample, placement in a lower caste happened because a person did not ulill hisDher dharma in a previous

lie. 2igher status was a ArewardA or good behavior in the past. 4lthough ,uddhism, li)e 2induism, emphasi/es the

soul8s yearning or understandings on a higher plane, it generally supported the notion that anyone o any social position

could ollow the Eightold 7ath successully. ,uddhists believed that changes in thought processes and lie styles brought

enlightenment, not the powers o one8s caste. 4lthough the ,uddha actively spread the new belies during his long

lietime, the new religion aced oppression ater his death rom 2indus who saw it as a threat to the basic social and

religious structure that held &ndia together. ,uddhism probably survived only because

the #auryan emperor 4sho)a converted to it and promoted its practice. 2owever, in the long run, ,uddhism did much

better in areas where it spread through cultural diusion, such as 0outheast 4sia, China, and Hapan.

C16B-C&46&0#

Three important belie systems 'Conucianism, +aoism, and 3egalism( emerged in China during the %arring 0tates

7eriod '40<$;;1 ,CE( between the >hou and 2an +ynasties. 4lthough the period was politically chaotic, it hosted a

cultural lowering that let a permanent mar) on Chinese history.

Conucius contemplated why China had allen into chaos, and concluded that the #andate o 2eaven had been lost

because o poor behavior o not only the Chinese emperor, but all his sub.ects as well. 2is plan or reestablishing Chinese

society prooundly aected the course o Chinese history and eventually spread to many other areas o 4sia as well. 2e

emphasi/ed the importance o harmony, order, and obedience and believed that i ive basic relationships were sound, all

o society would be, too"

EmperorDsub.ect $ the emperor has the responsibility to ta)e care o his sub.ects, and sub.ects must obey the

emperor

BatherDson $ the ather ta)es care o the son, and the son obeys the ather

1lder brotherDyounger brother $ the older brother ta)es care o the younger brother, who in turn obeys him

2usbandDwie $ the husband ta)es care o the wie, who in turn obeys him

BriendDriend $The only relationship that does not assume ine!uality should be characteri/ed by mutual care and

obedience

Conucius also deined the Asuperior manA $ one who e*hibits 9en ')indness(, li 'sense o propriety(, and Ciao

'ilial piety, or loyalty to the amily(.

Conucianism accepted and endorsed ine!uality as an important part o an ordered society. &t conirmed the power o the

emperor, but held him responsible or his people, and it reinorced the patriarchal amily structure that was already in

place in China. ,ecause Conucianism ocused on social order and political organi/ation, it is generally seen as a

philosophy rather than a religion. 9eligions are more li)ely to emphasi/e spiritual topics, not society and politics.

+41&0#

The ounder o +aoism is believed to have been 3ao/i, a spiritualist who probably lived in the 4th century ,CE. The

religion centers on the +ao 'sometimes reerred to as the A%ayA or A7athA(, the original orce o the cosmos that is an

eternal and unchanging principle that governs all the wor)ings o the world. The +ao is passive $ not active good nor bad $

but it .ust is. &t cannot be changed, so humans must learn to live with it. 4ccording to +aoism, human strivings have

brought the world to chaos because they resist the +ao. 4 chie characteristic is wuwei, or a disengagement rom the

aairs o the world, including government. The less government the better. 3ive simply, in harmony with nature. +aoism

encourages introspection, development o inner contentment, and no ambition to change the +ao.

,oth Conucianism and +aoism encourage sel )nowledge and acceptance o the ways things are. 2owever,

Conucianism is activist and e*troverted, and +aoism is relective and introspective. The same individual may believe in

the importance o both belie systems, unli)e many people in western societies who thin) that a person may only adhere to

one belie system or another.

3E=43&0#

The third belie system that arose rom the %arring 0tates 7eriod is legalism, and it stands in star) contrast to the other

belies. &t had no concern with ethics, morality, or propriety, and cared nothing about human nature, or governing

principles o the world. &nstead it emphasi/ed the importance o rule o law, or the imperative or laws to govern, not men.

4ccording to legalism, laws should be administered ob.ectively, and punishments or oenders should be harsh and swit.

3egalism was the philosophy o 0hi 2uangdi, the irst emperor, whose Iin +ynasty rescued China rom chaos. 2owever

when he died, the 2an emperors that ollowed deserted legalism and established Conucianism as the dominant

philosophy.

H-+4&0#

4s noted earlier, Hudaism was the irst clearly monotheistic religion. 4t the heart o the religion was a belie in a

Covenant, or agreement, between =od and the Hewish people, that =od would provide or them as long as they obeyed

him. The Ten Commandments set down rules or relationships among human beings, as well as human relationships to

=od. ,ecause they were specially chosen by =od, Hews came to see themselves as separate rom others and did not see)

to convert others to the religion. 4s a result, Hudaism has remained a relatively small religion. 2owever, its inluence on

other larger religions, including >oroastrianism, Christianity, and &slam is vast, and so it remains as a very signiicant

Aroot religion.A

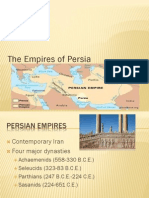

>oroastrianism is an early monotheistic religion that almost certainly inluenced and was inluenced by Hudaism, and it is

very diicult to )now which one may have emerged irst. ,oth religions thrived in the #iddle East, and adherents o both

apparently had contact with one another. >oroastrianism was the ma.or religion o 7ersia, a great land$based empire that

was long at war with 4ncient =reece and eventually con!uered by 4le*ander the =reat. The religion8s ounder was

>oroaster or >arathushtra, who saw the world immersed in a great struggle between good and evil, a concept that certainly

inluenced other monotheistic religions.

C29&0T&46&TF

Christianity grew directly out o Hudaism, with its ounder Hesus o 6a/areth born and raised as a Hew in the area .ust east

o the #editerranean 0ea. +uring his lietime, the area was controlled by 9ome as a province in the empire. Christianity

originated partly rom a long$standing Hewish belie in the coming o a #essiah, or a leader who would restore the Hewish

)ingdom to its ormer glory days. Hesus8 ollowers saw him as the #essiah who would cleanse the Hewish religion o its

rigid and haughty priests and assure lie ater death to all that ollowed Christian precepts. &n this way, its appeal to

ordinary people may be compared to that o ,uddhism, as it struggled to emerge rom the 2indu caste system.

Christianity8s broad appeal o the masses, as well as deliberate conversion eorts by its early apostles, meant that the

religion grew steadily and eventually became the religion with the most ollowers in the modern world.

Hesus was a prophet and teacher whose ollowers came to believe that he was the son o =od. 2e advocated a moral code

based on love, charity, and humility. 2is disciples predicted a inal .udgment day when =od would reward the righteous

with immortality and condemn sinners to eternal hell. Hesus was arrested and e*ecuted by 9oman oicials because he

aroused suspicions among Hewish leaders, and he was seen by many as a dangerous rebel rouser. 4ter his death, his

apostles spread the aith. Especially important was 7aul, a Hew who was amiliar with =reco$9oman culture. 2e e*plained

Christian principles in ways that =ree)s and 9omans understood, and he established churches all over the eastern end o

the #editerranean, and even as ar away as 9ome.

Christianity grew steadily in the 9oman Empire, but not without clashes with 9oman authorities. Eventually in the 4th

century CE, the Emperor Constantine was converted to Christianity and established a new capital in the eastern city o

,y/antium, which he renamed Constantinople. 4s a result, the religion grew west and north rom 9ome, and also east

rom Constantinople, greatly e*tending its reach.

,y the end o the classical era, these ma.or belie systems had e*panded to many areas o the world, and with the all o

empires in the late classical era, came to be ma.or orces in shaping world history. 1ne ma.or religion $ &slam $ remained

to be established in the 5th century as part o the ne*t great period that e*tended rom 600 to 1450 CE.

THE ISLAMIC ;ORLD

&slam $ the religion with the second largest number o supporters in the world today $ started in the sparsely

populated 4rabian 7eninsula among the ,edouins, a nomadic group that controlled trade routes across the desert. &n the

early 5th century, a ew trade towns, such as #ecca and #edina, were centers or camel caravans that were a lin) in the

long distance trade networ) that stretched rom the #editerranean to eastern China. #ecca was also was the destination

or religious pilgrims who traveled there to visit shrines to countless gods and spirits. &n the center o the city was a simple

house o worship called the Ga8aba, which contained among its many idols the ,lac) 0tone, believed to have been placed

their by 4braham, the ounder o Hudaism. Hews and Christians inhabited the city, and they mi*ed with the ma.ority who

were polytheistic.

THE FOUNDIN, OF ISLAM

&slam was ounded in #ecca by #uhammad, a trader and business manager or his wie, Ghadi.ah, a wealthy

businesswoman. #uhammad was interested in religion, and when he was about 40 he began visiting caves outside the city

to ind !uiet places to meditate. 4ccording to #uslim belie, one night while he was meditating #uhammad heard the

voice o the angel =abriel, who told him that he was a messenger o =od. #uhammad became convinced that he was the

last o the prophets, and that the one true god, 4llah, was spea)ing to him through =abriel. 2e came bac) into the city to

begin spreading the new religion, and he insisted that all other gods were alse. 2is ollowers came to be called #uslims,

or people who have submitted to the will o 4llah.

#uhammad8s ministry became controversial, partly because city leaders eared that #ecca would lose its position as a

pilgrimage center o people accepted #uhammad8s monotheism. &n 6;; C.E. he was orced to leave #ecca or ear o his

lie, and this amous light to the city o Fathrib became )nown as the 2i.rah, the oicial ounding date or the new

religion. &n Fathrib he converted many to &slam, and he renamed the city A#edina,A or Acity o the 7rophet.A 2e called the

community the umma, a term that came to reer to the entire population o #uslim believers.

4s &slam spread, #uhammad continued to draw the ire o #ecca8s leadership, and he became an astute military leader in

the hostilities that ollowed. &n 6<0, the 7rophet and 10,000 o his ollowers captured #ecca and destroyed the idols in

the Ga8aba. 2e proclaimed the structure as the holy structure o 4llah, and the ,lac) 0tone came to symboli/ed the

replacement o polytheism by the aith in one god.

ISLAMIC BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

The Bive 7illars o aith are ive duties at the heart o the religion. These practices represent a #uslim8s submission to the

will o =od.

Baith $ %hen a person converts to &slam, he or she recites the +eclaration o Baith, AThere is no =od but 4llah,

and #uhammad is the #essenger o 4llah.A This phrase is repeated over and over in #uslim daily lie.

7rayer $ #uslims must ace the city o #ecca and pray ive times a day. The prayer oten ta)es place in mos!ues

'&slamic holy houses(, but #uslims may stop to pray anywhere. &n cities and towns that are primarily #uslim, a

mue//in calls people to prayer rom a minaret tower or all to hear.

4lms $ 4ll #uslims are e*pected to give money or the poor through a special religious ta* called alms.

#uhammad taught the responsibility to support the less ortunate.

Basting $ +uring the &slamic holy month o 9amadan, #uslims ast rom sunup to sundown. 1nly a simple meal

is eaten at the end o the day that reminds #uslims that aith is more important than ood and water.

7ilgrimage $ #uslims are e*pected to ma)e a pilgrimage to #ecca at least once in their lietime. This event,

called the ha.., ta)es place once a year, and people arrive rom all over the world in all )inds o conveyances to

worship at the Ga8aba and several other holy sites nearby. 4ll pilgrims wear an identical white garment to show

their e!uality beore 4llah.

The single most important source o religious authority or #uslims is the Iur8an, the holy boo) believed to be the actual

words o 4llah. 4ccording to &slam, 4llah e*pressed his will through the 4ngel =abriel, who revealed it to #uhammad.

4ter #uhammad8s death these revelations were collected into a boo), the Iur8an. #uhammad8s lie came to be seen as

the best model or proper living, called the 0unna. -sing the Iur8an and the 0unna or guidance, early ollowers

developed a body o law )nown as shari8a, which regulated the amily lie, moral conduct, and business and community

lie o #uslims. 0hari8a still is an important orce in many #uslim countries today even i they have separate bodies o

oicial national laws. &n the early days o &slam, shari8a brought a sense o unity to all #uslims.

THE SPREAD OF ISLAM

#uhammad died in 6<; CE, only ten years ater the hi.rah, but by that time, &slam had spread over much o the 4rabian

7eninsula. 0ince #uhammad8s lie represented the Aseal o the prophetsA 'he was the last one(, anyone that ollowed had

to be a very dierent sort. The government set up was called a caliphate, ruled by a caliph 'a title that means AsuccessorA

or Adeputy( selected by the leaders o the umma. The irst caliph was 4bu$,a)r, one o #uhammad8s close riends. 2e

was ollowed by three successive caliphs who all had )nown the 7rophet, and were Arightly guidedA by the Iur8an and the

memory o #uhammad. ,y the middle o the Eth century #uslim armies had con!uered land rom the 4tlantic 1cean to

the &ndus 9iver, and the caliphate stretched 6000 miles east to west.

9eligious /eal certainly played an important role in the rapid spread o &slam during the 5th and Eth centuries C.E.

2owever, several other actors help to e*plain the phenomenon"

%ell$disciplined armies $ Bor the most part the #uslim commanders were able, war tactics were eective, and the

armies were eiciently organi/ed.

%ea)ness o the ,y/antine and 7ersian Empires $ 4s the &slamic armies spread north, they were aided by the

wea)ness o the empires they sought to con!uer. ,oth the ,y/antine and 7ersian Empires were wea)er than they

had been in previous times, and many o their sub.ects were willing to convert to the new religion.

Treatment o con!uered peoples $ The Iur8an orbid orced conversions, so con!uered people were allowed to

retain their own religions. #uslims considered Christians and Hews to be superior to polytheistic people, not only

because they were monotheistic, but also because they too adhered to a written religious code. 4s a result,

#uslims called Christians and Hews Apeople o the boo).A #any con!uered people chose to convert to &slam, not

only because o its appeal, but because as #uslims they did not have to pay a poll ta*.

THE SUNNI-SHI<A SPLIT

The 4rab tribes had ought with one another or centuries beore the advent o &slam, and the religion ailed to prevent

serious splits rom occurring in the caliphate. Each o the our caliphs was murdered by rivals, and the death o

#uhammad8s son$in$law 4li in 661 triggered a civil war. 4 amily )nown as the -mayyads emerged to ta)e control, but

4li8s death spar)ed a undamental division in the umma that has lasted over the centuries. The two main groups were"

0unni $ &n the interest o peace, most #uslims accepted the -mayyads8 rule, believing that the caliph should

continue to be selected by the leaders o the #uslim community. This group called themselves the 0unni, meaning

Athe ollowers o #uhammad8s e*ample.A

0hi8a $ This group thought that the caliph should be a relative o the 7rophet, and so they re.ected the -mayyads8

authority. A0hi8aA means Athe party o 4li,A and they sought revenge or 4li8s death.

Even though the caliphate continued or many years, the split contributed to its decline as a political system. The caliphate

combined political and religious authority into one huge empire, but it eventually split into many political parts. The areas

that it con!uered remained united by religion, but the tendency to all apart politically has been a ma.or eature o #uslim

lands. #any other splits ollowed, including the ormation o the 0ui, who reacted to the lu*urious lives o the later

caliphs by pursuing a lie o poverty and devotion to a spiritual path. They shared many characteristics o other ascetics,

such as ,uddhist and Christian mon)s, with their emphasis on meditation and chanting.

THE CHAN,IN, STATUS OF ;OMEN

The patriarchal system characteri/ed most early civili/ations, and 4rabia was no e*ception. 2owever, women en.oyed

rights not always given in other lands, such as inheriting property, divorcing husbands, and engaging in business ventures

'li)e #uhammad8s irst wie, Ghadi.ah.( The Iur8an emphasi/ed e!uality o all people beore 4llah, and it outlawed

emale inanticide, and provided that dowries go directly to brides. 2owever, or the most part, &slam reinorced male

dominance. The Iur8an and the shari8a recogni/ed descent through the male line, and strictly controlled the social and

se*ual lives o women to ensure the legitimacy o heirs. The Iur8an allowed men to ollow #uhammad8s e*ample to ta)e

up to our wives, and women could have only one husband.

#uslims also adopted the long$standing custom o veiling women. -pper class women in #esopotamia wore veils as

early as the 1<th century ,CE, and the practice had spread to 7ersia and the eastern #editerranean long beore

#uhammad lived. %hen #uslims con!uered these lands, the custom remained intact, as well as the practice o women

venturing outside the house only in the company o servants or chaperones.

ARTS2 SCIENCES2 AND TECHNOLO,IES

,ecause &slam was always a missionary religion, learned oicials )nown as ulama ' Apeople with religious )nowledgeA(

and !adis 'A.udgesA( helped to bridge cultural dierences and spread &slamic values throughout the dar al$&slam, as

&slamic lands came to be )nown. Bormal educational institutions were established to help in this mission. ,y the 10th

century CE, higher education schools )nown as madrasas had appeared, and by the 1;th century they were well

established. These institutions, oten supported by the wealthy, attracted scholars rom all over, and so we see a lowering

o arts, sciences, and new technologies in &slamic areas in the 1;th through 15th centuries.

%hen 7ersia became a part o the caliphate, the con!uerors adapted much o the rich cultural heritage o that land.

#uslims became ac!uainted, then, with the literary, artistic, philosophical, and scientiic traditions o others. 7ersians was

the principle language o literature, poetry, history, and political theory, and the verse o the 9ubaiyat by

1mar Ghayyam is probably the most amous e*ample. 4lthough many o the stories o The 4rabian 6ights or The

Thousand and 1ne 6ights were passed down orally rom generation to generation, they were written down in 7ersian.

&slamic states in northern &ndia also adapted mathematics rom the people they con!uered, using their 2indi numerals,

which Europeans later called A4rabic numerals.A The number system included a symbol or /ero, a very important

concept or basic calculations and multiplication. #uslims are generally credited with the development o mathematical

thought, particularly algebra. #uslims also were interested in =ree) philosophy, science, and medical writings. 0ome

were especially involved in reconciling 7lato8s thoughts with the teachings o &slam. The greatest historian and geographer

o the 14th century was &bn Ghaldum, a #oroccan who wrote a comprehensive history o the world. 4nother &slamic

scholar, 6asir al$+in, studied and improved upon the cosmological model o 7tolemy, an ancient =ree)

astronomer. 6asir al$+in8s model was almost certain used by 6icholas Copernicus, a 7olish mon) and astronomer who is

usually credited with developing the heliocentric model or the solar system.

INTERRE,IONAL NET;OR=S AND CONTACTS

Contacts among societies in the #iddle East, the &ndian subcontinent, and 4sia increased signiicantly between 600 and

1450 CE, and 4rica and Europe became much more important lin)s in the long$distance trade networ)s. ,oth the &ndian

1cean Trade and the 0il) 9oad were disrupted by ma.or migrations during this period, but both recovered and eventually

thrived. Europeans were irst brought into the trade loop through cities li)e :enice and =enoa on the #editerranean, and

the Trans$0aharan trade became more vigorous as ma.or civili/ations developed south o the 0aharan.

Two ma.or sea$trading routes $ those o the #editerranean 0ea and the &ndian 1cean $ lin)ed the newly created #uslim

Empire together, and 4rabic sailors come to dominate the trade. #uslims also were active in the 0il) 9oad trade to &ndia

and China. To encourage the low o trade, #uslim money changers set up ban)s throughout the caliphate so that

merchants could easily trade with those at ar distances. Cities along the trade routes became cosmopolitan mi*tures o

many religions and customs.

AFRICAN SOCIETIES AND EMPIRES

-ntil about 600 CE, most 4rican societies based their economies on hunting and gathering or simple agriculture and

herding. They centered their social and political organi/ation around the amily, and none had a centrali/ed government.

,eginning around 640, &slam spread into the northern part o the continent, bringing with it the uniying orces o

religious practices and law, the shari8a. 4s &slam spread, many 4rican rulers converted to the new religion, and

centrali/ed states began to orm. The primary agents o trade, the ,erbers o the 0ahara, became #uslims, although they

retained their identities and tribal loyalties. 4s a result, &slam mi*ed with native cultures to create a synthesis that too)

dierent orms in dierent places in northern 4rica. This gradual, nonviolent spread o &slam was very conducive to

trade, especially since people south o the 0ahara had gold.

,etween 600 and 1450 CE, two ma.or empires emerged in %est 4rica, .ust south o the 0ahara +esert"

=hana $ ,y the 500s, a arming people called the 0onin)e had ormed an empire that they called =hana 'Awar

chieA( that was growing rich rom ta*ing the goods that traders carried through their territory. Their most

important asset was gold rom the 6iger 9iver area that they traded or salt rom the 0ahara. The 4rab and ,erber

traders also carried cloth, weapons, and manuactured goods rom ports on the #editerranean. =hana8s )ing had

e*clusive rights to the gold, and so controlled its supply to )eep the price high. The )ing also commanded an

impressive army, and so the empire thrived. 3i)e the 4ricans along the #editerranean, =hana8s rulers and elites

converted to &slam, but most others retained their native religions.

#ali $ +uring the 11th century, the 4lmoravids, a #uslim group rom northern 4rica, con!uered =hana. ,y the

1<th century, a new empire, called #ali, dominated %est 4rica. The empire began with #ande$spea)ing people

south o =hana, but it grew to be larger, more powerul, and richer than =hana had been. #ali too based its

wealth on gold. 6ew deposits were ound east o the 6iger 9iver, and 4rican gold became a basic commodity in

long distance trade. #ali8s irst great leader was 0undiata, whose lie inspired an epic poem $The 3egend

o 0undiata $ that was passed down rom one generation to the ne*t. 2e deeated )ingdoms around #ali, and also

proved to be an aective administrator. 7erhaps even more amous was #ansu #usa, a 14th century ruler. 2e is

best )nown or giving away so much gold as he traveled rom #ali to #ecca or the ha.. that he set o a ma.or

round o inlation, seriously aecting economies all along the long$distance trade routes. #ali8s capital city,

Timbu)tu, became a world center o trade, education and sophistication.

The 0wahili city$states $ The people who lived in trade cities along the eastern coast o 4rica provided a very

important lin) or long$distance trade. The cities were not united politically, but they were well developed, with a

great deal o cultural diversity and sophisticated architecture. The people were )nown collectively as the 0wahili,

based on the language that they spo)e $ a combination o ,antu and 4rabic. #ost were #uslims, and the sailors

were renowned or their ability to maneuver their small boats through the &ndian 1cean to &ndia and other areas o

the #iddle East via the 9ed 0ea and bac) again.

THE CHRISTIAN CRUSADES (LATE 11TH THROU,H 1/TH CENTURIES C.E.)

7ope -rban && called or the Christian Crusades in 10J5 with the urgent message that )nights rom %estern Europe must

deend the Christian #iddle East, especially the 2oly 3ands o the eastern #editerranean, rom Tur)ish #uslim

invasions. The Eastern 1rthodo* ,y/antine emperor called on -rban or help when #uslims were right outside

Constantinople. %hat resulted over the ne*t two centuries was not the recovery o the #iddle East or Christianity, but

many other unintended outcomes. ,y the late 1<th century, the Crusades ended, with no permanent gains made or

Christians. &ndeed, Constantinople eventually was destined to be ta)en by #uslims in 145< and renamed &stanbul.

&nstead o bringing the victory that the )nights sought, the Crusades had the ultimate conse!uence o bringing Europeans

s!uarely into the ma.or world trade circuits. The societies o the #iddle East were much richer than European )ingdoms

were, and the )nights encountered much more sophisticated cultures there. They brought home all )inds o trading goods

rom many parts o the world and stimulated a demand in Europe or oreign products, such as sil), spices, and gold. Two

&talian cities $ :enice and =enoa $ too) advantage o their geographic location to arrange or water transportation or

)nights across the #editerranean to the 2oly 3ands. 1n the return voyages, they carried goods bac) to European mar)ets,

and both cities became !uite wealthy rom the trade. This wealth eventually became the basis or great cultural change in

Europe, and by 1450, European )ingdoms were poised or the eventual control o long$distance trade that they eventually

gained during the 1450$1550 era.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE MON,OLS

The #ongol invasions and con!uests o the 1<th century are arguably among the most inluential set o events in world

history. This nomadic group rom Central 4sia swept south and east, .ust as the 2uns had done several centuries beore.

They con!uered China, &ndia, the #iddle East, and the budding )ingdom o 9ussia. & not or the ateul death o the

=reat Ghan 1gadai, they might well have con!uered Europe as well. 4s it is, the #ongols established and ruled the

largest empire ever assembled in all o world history. 4lthough their attac)s at irst disrupted the ma.or trade routes, their

rule eventually brought the 7a* #ongolica, or a peace oten compared to the 7a* 9omana established in ancient times

across the 9oman Empire.

THE RISE OF THE MON,OLS

The #ongols originated in the Central 4slian steppes, or dry grasslands. They were pastoralists, organi/ed loosely into

)inship groups called clans. Their movement almost certainly began as they sought new pastures or their herds, as had so

many o their predecessors. #any historians believe that a severe drought caused the initial movement, and that the

#ongol8s superior ability as horsemen sustained their successes.

4round 1;00 CE, a #ongol )han 'clan leader( named Temu.in uniied the clans under his leadership. 2is acceptance o

the title =enghis Ghan, or Auniversal leaderA tells us something o his ambitions or his empire. 1ver the ne*t ;1 years, he

led the #ongols in con!uering much o 4sia. 4lthough he didn8t con!uer China in his lietime, he cleared the way or its

eventual deeat by #ongol orces. 2is sons and grandsons continued the con!uests until the empire eventually reached its

impressive si/e. =enghis Ghan is usually seen as one o the most talented military leaders in world history. 2e organi/ed

his warriors by the Chinese model into armies o 10,000, which were grouped into 1,000 man brigades, 100$man

companies, and 10$man platoons. 2e ensured that all generals were either )insmen or trusted riends, and they remained

ama/ingly loyal to him. 2e used surprise tactics, li)e a)e retreats and alse leads, and developed sophisticated catapults

and gunpowder charges.

The #ongols were inally stopped in Eurasia by the death o 1godai, the son o =enghis Ghan, who had become the

=reat Ghan centered in #ongolia when his ather died. 4t his death, all leaders rom the empire went to the #ongol

capital to select a replacement, and by the time this was accomplished, the invasion o Europe had lost its momentum. The

#ongols were also contained in &slamic lands by the #amlu) armies o Egypt, who had been enslaved by the 4bbasid

Caliphate. These orces matched the #ongols in horsemanship and military s)ills, and deeated them in battle in 1;60

beore the #ongols could reach the +ardanelle strait. The #ongol leader 2ulegu decided not the press or urther

e*pansion.

THE MON,OL OR,ANIZATION

The #ongol invasions disrupted all ma.or trade routes, but =enghis Ghan8s sons and grandsons organi/ed the vast empire

in such a way that the routes soon recovered. They ormed our Ghanates, or political organi/ations each ruled by a

dierent relative, with the ruler o the original empire in Central 4sia designated as the A=reat Ghan,A or the one that

ollowed in the steps o =enghis. 1nce the #ongols deeated an area, generally by brutal tactics, they were generally

content to e*tract tribute 'payments( rom them, and oten allowed con!uered people to )eep many o their customs. The

#ongol )hans were spread great distances apart, and they soon lost contact with one another. #ost o them adopted many

customs, even the religions, o the people they ruled. Bor e*ample, the &l$)han that con!uered the last caliphate in the

#iddle East eventually converted to &slam and was a great admirer o the sophisticated culture and advanced technologies

o his sub.ects. 0o the #ongol Empire eventually split apart, and the #ongols themselves became assimilated into the

cultures that they had Acon!uered.A

T;O TRAVELLERS

#uch o our )nowledge o the world in the 1<th and14th century comes rom two travelers, &bn ,attuta and #arco 7olo,

who widened )nowledge o other cultures through their writings about their .ourneys.

#arco 7olo $ &n the late 1<th century, #arco 7olo let his home in :enice, and eventually traveled or many years

in China. 2e was accompanied by his ather and uncle, who were merchants an*ious to stimulate trade between

:enice along the trade routes east. 7olo met the Chinese ruler Gublai Ghan '=enghis Ghan8s grandson(, who was

interested in his travel stories and convinced him to stay as an envoy to represent him in dierent parts o China.

2e served the )han or 15 years beore returning home, where he was captured by =enoans at war with :enice.

%hile in prison, he entertained his cellmates with stories about China. 1ne prisoner compiled the stories into a

boo) that became wildly popular in Europe, even though many did not believe that 7olo8s stories were true.

Europeans could not believe that the abulous places that 7olo described could ever e*ist.

&bn ,attutu $ This amous traveler and proliic writer o the 14th century spent many years o his lie visiting

many places within &slamic Empires. 2e was a #oroccan legal scholar who let his home or the irst time to

ma)e a pilgrimage to #ecca. 4ter his ha.. was completed, he traveled through #esopotamia and 7ersia, then

sailed down the 9ed 0ea and down the east 4rican coast as ar south as Gilwa. 2e later traveled to &ndia, the

,lac) 0ea, 0pain, #ali, and the great trading cities o Central 4sia. 2e wrote about all o the places he traveled

and compiled a detailed .ournal that has given historians a great deal o inormation about those places and their

customs during the 14th century. 4 devout #uslim who generally e*pected ine hospitality, &bn ,attutu seldom

)ept his opinions to himsel, and he commented reely on his approval or disapproval o the things that he saw.

4lthough ew people traveled as much as #arco 7olo and &bn ,attutu did, the large empires o the #ongols and other

nomadic peoples provided a political oundation or the e*tensive cross$cultural interaction o the era.

CHINA<S HE,EMON:

2egemony occurs when a civili/ation e*tends its political, economic, social, and cultural inluence over others. Bor

e*ample, we may reer to the hegemony o the -nited 0tates in the early ;1st century, or the conlicting hegemony o the

-nited 0tates and 9ussia during the Cold %ar Era. &n the time period between 600 and 1450 CE, it was impossible or one

empire to dominate the entire globe, largely because distance and communication were so diicult. ,oth the &slamic

caliphates and the #ongol Empire ell at least partly because their land space was too large to control eectively. 0o the

best any empire could do was to establish regional hegemony. +uring this time period, China was the richest and most

powerul o all, and e*tended its reach over most o 4sia.

THE >,OLDEN ERA> OF THE TAN, AND SON,

+uring the period ater the all o the 2an +ynasty in the <rd century C.E., China went into a time o chaos, ollowing the

established pattern o dynastic cycles. +uring the short$lived 0ui +ynasty '5EJ$61E C.E.(, China began to restore

centrali/ed imperial rule. 4 great accomplishment was the building o the =rand Canal, one o the world8s largest

waterwor)s pro.ects beore the modern era. The canal was a series o manmade waterways that connected the ma.or rivers

and made it possible or China to increase the amount and variety o internal trade. %hen completed it was almost 1;40

miles long, with roads running parallel to the canal on either side.

STREN,THS OF THE TAN,

&n 61E a rebel leader sei/ed China8s capital, Ci8an, and proclaimed himsel the emperor o the Tang +ynasty, an empire

destined to last or almost three hundred years 'till J05(. -nder the Tangs China regained strength and emerged as a

powerul and prosperous society. Three ma.or accomplishments o the Tang account or their long$lasting power"

4 strong transportation and communications system $ The =rand Canal contributed to this accomplishment, but

the Tang rulers also built and maintained an advanced road system, with inns, postal stations, and stables to

service travelers along the way. 7eople traveled both on oot and by horse, and the emperor used the roads to send

messages by courier in order to )eep in contact with his large empire.

The e!ual$ield system $ The emperor had the power to allocate agricultural land to individuals and amilies, and

the e!ual$ield system was meant to ensure that land distribution was air and e!uitable. 7art o the emperor8s

motivation was to control the amount o land that went to powerul amilies, a problem that had caused strong

challenges to the emperor8s mandate during the 2an +ynasty. The system wor)ed until the Jth century, when

inluential amilies again came to accumulate much o the land.

4 merit$based bureaucracy $This system was well developed during the 2an +ynasty, but the Tang made good use

o it by recruiting government oicials who were well educated, loyal, and eicient. 4lthough powerul amilies

used their resources to place relatives in government positions, most bureaucrats won their posts because o

intellectual ability.

Tang China e*tended its hegemony by e*tracting tribute 'gits and money( rom neighboring realms and people. China

was oten called Athe #iddle Gingdom,A because its people saw their civili/ation at the center o all that paid it honor. The

empire itsel was ar larger than any beore it, ollowing along the river valleys rom :ietnam to the south and #anchuria

to the north, and e*tending into parts o Tibet. &n 66E, the Tang overran Gorea, and established a vassal )ingdom

called 0illa.

RELI,IOUS ISSUES

3ong beore the Tang +ynasty was ounded, ,uddhism had made its way into China along the trade routes. ,y the pre$

Tang era, ,uddhist monasteries had so grown in inluence that they held huge tracts o land and e*erted political

inluence. #any rulers o the pre$Tang era, particularly those rom nomadic origins, were devout ,uddhists. #any

variations o ,uddhism e*isted, with #ahayana ,uddhism prevailing, a ma.or branch o the religion that allowed a great

deal o variance o ,uddha8s original teachings. Empress %u '6J0$505( was one o ,uddhism8s strongest supporters,

contributing large sums o money to the monasteries and commissioning many ,uddhist paintings and sculptures. ,y the

mid$Jth century, more than 50,000 monasteries e*isted in China.

Conucian and +aoist supporters too) note o ,uddhism8s growing inluence, and they soon came to challenge it. 7art o

the conlict between Conucianism and ,uddhism was that in many ways they were opposite belies, even though they

both condoned ArightA behavior and thought. Conucianism emphasi/ed duties owed to one8s society, and placed its

highest value on order, hierarchy, and obedience o superiors. ,uddhism, on the other hand, encouraged its supporters to

withdraw rom society, and concentrate on personal meditation. Binally in the Jth century, Conucian scholar$bureaucrats

conspired to convince the emperors to ta)e lands away rom the monasteries through the e!ual$ield system. -nder

emperor %u/ong, thousands o monasteries were burned, and many mon)s and nuns were orced to abandon them and

return to civilian lie.

6ot only was ,uddhism wea)ened by these actions, but the Tang +ynasty lost overall power as well. 2owever,

Conucianism emerged as the central ideology o Chinese civili/ation and survived as such until the early ;0th century.

THE FOUNDIN, OF THE SON, D:NAST:

+uring the Eth century, warlords began to challenge the Tang rulers, and even though the dynasty survived until J05 C.E.,

the political divisions encouraged nomadic groups to invade the ringes o the empire. %orsening economic conditions led

to a succession o revolts in the Jth century, and or a ew years China ell into chaos again. 2owever, recovery came

relatively !uic)ly, and a military commander emerged in J60 to reunite China, beginning the 0ong +ynasty. The 0ong

emperors did not emphasi/e the military as much as they did civil administration, industry, education, and the arts. 4s a

result, the 0ong never established hegemony over as large an area as the Tang had, and political disunity was a constant

threat as long as they held power. 2owever, the 0ong presided over a Agolden eraA o Chinese civili/ation characteri/ed by

prosperity, sophistication, and creativity.

The 0ong vastly e*panded the bureaucracy based on merit by sponsoring more candidates with more opportunities to

learn Conucian philosophy, and by accepting more candidates or bureaucratic posts than the 0ui and Tang.

PROBLEMS UNDER THE SON,

The 0ong created a more centrali/ed government than ever beore, but two problems plagued the empire and eventually

brought about its all"

Binances $ The e*pansion o the bureaucracy meant that government e*penses s)yroc)eted. The government

reacted by raising ta*es, but peasants rose in two ma.or rebellions in protest. +espite these warnings, bureaucrats

reused to give up their powerul positions.

#ilitary $ China had always needed a good military, partly because o constant threats o invasion by numerous

nomadic groups. The 0ong military was led by scholar bureaucrats with little )nowledge or real interest in

directing armies. The Hurchens, a northern nomadic group with a strong military, con!uered other nomads around

them, overran northern China, and eventually capturing the 0ong capital. The 0ong were let with only the

southern part o their empire that was eventually con!uered by the #ongols in 1;5J C.E.

ECONOMIC REVOLUTIONS OF THE TAN, AND SON, D:NASTIES

Even though the 0ong military wea)ness eventually led to the dynasty8s demise, it is notable or economic revolutions that

led to Chinese hegemony during the era. China8s economic growth in turn had implications or many other societies

through the trade that it generated along the long$distance routes. The changes actually began during the Tang +ynasty

and became even more signiicant during 0ong rule. 0ome characteristics o these economic revolutions are"

&ncreasing agricultural production $ ,eore this era, Chinese agriculture had been based on the production o

wheat and barley raised in the north. The Tang con!uest o southern China and :ietnam added a whole new

capability or agriculture@ the cultivation o rice. &n :ietnam they made use o a new strain o ast$ripening rice

that allowed the production o two crops per year. 4gricultural techni!ues improved as well, with the use o the

heavy iron plow in the north and water bualoes in the south. The Tang also organi/ed e*tensive irrigation

systems, so that agricultural production was able to move outward rom the rivers.

&ncreasing population $ China8s population about 600 C.E. was about 45 million, but by 1;00 'the 0ong +ynasty(

it had risen to about 115 million. This growth occurred partly because o the agricultural revolution, but also

because distribution o ood improved with better transportation systems, such as the =rand Canal and the

networ) o roads throughout the empire.

-rbani/ation $ The agricultural revolution also meant that established cities grew and new ones were created.

%ith its population o perhaps ;,000,000, the Tang capital o Ci8an was probably the largest city in the world. The

0ong capital o 2ang/hou was smaller, with about 1,000,000 residents, but it too was a cosmopolitan city with

large mar)ets, public theatres, restaurants, and crat shops. #any other Chinese cities had populations o more

than 100,000. ,ecause rice production was so successul and 0il) 9oad and &ndian 1cean trade was vigorous,

other armers could concentrate on specialty ruits and vegetables that were or sale in urban mar)ets.

Technological innovations $ +uring Tang period cratsmen discovered techni!ues or producing porcelain that was

lighter, thinner, more useul, and much more beautiul. Chinese porcelain was highly valued and traded to many

other areas o the world, and came to be )nown broadly as chinaware. The Chinese also developed superior

methods or producing iron and steel, and between the Jth and 1;th centuries, iron production increased tenold.

The Tang and 0ong are best )nown or the new technologies they invented, such as gunpowder, movable type

printing, and seaaring aids, such as the magnetic compass. =unpowder was irst used in bamboo lame throwers,

and by the 11th century inventors had constructed crude bombs.

Binancial inventions $ ,ecause trade was so strong and copper became scarce, Chinese merchants developed

paper money as an alternative to coins. 3etters o credit called Alying cashA allowed merchants to deposit money

in one location and have it available in another. The Chinese also used chec)s which allowed drawing unds

deposited with ban)ers.

NEO-CONFUCIANISM

The conlict between ,uddhism and Conucianism during the late Tang +ynasty eased under the 0ongs, partly because o

the development o 6eo$Conucianism. Classical Conucians were concerned with practical issues o politics and

morality, and their main goal was an ordered social and political structure. 6eo$Conucians also became amiliar with

,uddhist belies, such as the nature o the soul and the individual8s spiritual relationships. They came to reer to li, a

concept that deined a spiritual presence similar to the universal spirit o both 2induism and ,uddhism. This new orm o

Conucianism was an important development because it reconciled Conucianism with ,uddhism, and because it

inluenced philosophical thought in China, Gorea, :ietnam, and Hapan in all subse!uent eras.

PATRIARCHAL SOCIAL STRUCTURES

4s wealth and agricultural productivity increase, the patriarchal social structure o Chinese society also tightened. %ith

amily ortunes to preserve, elites insured the purity o their lines by urther conining women to the home. The custom o

oot binding became very popular among these amilies. Boot binding involved tightly wrapping young girls8 eet so that

natural growth was seriously impaired. The result was a tiny malormed oot with the toes curled under and the bones

brea)ing in the process. The women generally could not wal) e*cept with canes. 7easants and middle class women did

not bind their eet because it was impractical, but or elite women, the practice $ li)e wearing veils in &slamic lands $

indicated their subservience to their male guardians.

=UBLAI =HAN2 THE :UAN D:NAST:2 AND THE EARL: MIN, (191?-1450 C.E.)

The #ongols began to breach the =reat %all under =enghis Ghan, but the southern 0ong was not con!uered until his

grandson, Gublai Ghan captured the capital and set up a new capital in ,ei.ing, which he called Ghanbalu), or Acity o the

Ghan.A This was the city that #arco 7olo described to the world as the inest and richest in all the world. -nder Gublai

Ghan, China was uniied, and its borders grew signiicantly. 4lthough #ongols replaced the top bureaucrats, many lower

Conucian oicials remained in place, and the Ghan clearly respected Chinese customs and innovations. 2owever,

whereas the 0ong had emphasi/ed cultural and organi/ational values, the #ongols were most adept in military aairs and

con!uest. 4lso, even though trade lourished during the Tang and 0ong era, merchants had a much lower status than

scholars did. Gublai Ghan and his successors put a great deal o eort into con!uering more territory in 4sia, and they