Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Germans Tear Gas Mask

Uploaded by

Volkan Aran0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views10 pagesAbout tear gas mask. Object studies

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAbout tear gas mask. Object studies

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views10 pagesGermans Tear Gas Mask

Uploaded by

Volkan AranAbout tear gas mask. Object studies

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

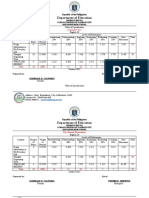

Some Problems of Gas Warfare

Author(s): Ellwood B. Spear

Source: The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Mar., 1919), pp. 275-283

Published by: American Association for the Advancement of Science

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/7061 .

Accessed: 09/09/2013 09:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

American Association for the Advancement of Science is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Scientific Monthly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE 275

SOME PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE'

By Dr. ELLWOOD B. SPEAR

T HE initial use of

gas by

the Germans at

Ypres

in 1915 and

the

subsequent adoption

of gas warfare

by

the allied

armies introduced a large number of problems of vital impor-

tance to the nations involved in the World War. While these

problems taxed to a very great degree the ingenuity of the sci-

entist, the engineer, the military strategist and the manufac-

turer, they by no means lacked that fascination which charac-

terizes all research, an intellectual journey into the unknown.

Although this fascination was augmented by the fact that the

problems were nearly all new and the field almost

limitless,

nevertheless the flight of the imagination was circumscribed by

the stern condition of immediate practical utility and the neces-

sity for rapid solution.

Another feature especially prominent in the early stages of

gas warfare was the unstable nature of the problems. The act

on the screen was continually changing. The solutions of yes-

terday might not meet the requirements of to-day, and the prac-

tise of to-day might become archaic by to-morrow. The kalei-

doscopic nature of these changes can be best illustrated by a

brief account of the tactics of the offensive and the development

of the defense, the chief feature of which is the gas mask.

The first object of the use of gas by the military strategist

was, of course, to destroy the enemy. With this purpose in

view the Germans made their first gas attack by means of poi-

sonous clouds. Chlorine was compressed into cylinders that

were placed in their own front-line trenches. The cylinders

were fitted with a suitable hose and nozzle so that at the ap-

pointed time the valves could be opened and the gas allowed to

escape. Chlorine is particularly adapted for this method of

attack. It is fairly easily compressible into the form of a liquid,

but six atmospheres being necessary at ordinary temperature.

It is very poisonous, one to two parts per ten thousand of air

sufficing to result in death if breathed for five minutes. It has

the additional property of being heavy, about two and one-half

times the weight of an equal volume of air. Consequently it

does not tend to rise rapidly into the upper air, but, on the con-

1 Figures 1 to 8 inclusive are published with the permission of the

Director of the Chemical Warfare Service.

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

276 THE SCIENTIFIC MONTHLY

-,

:

trary,

rolls

along

the

ground,

seeking

out and

filling

all the

low places such as trenches,

dugouts,

shell holes and so on.

The result of the attack is

I 2i |now a matter of history. The

French Colonial black

troops

'z i t t.t

broke and fled. Who can blame

GERMAN GASCLINDER DETAILOFGA5YLlNIXR them ? The Canadians went into

FOR

15 this particular sector twelve

thousand strong. When they

were relieved five days later but two thousand remained alive.

A very large portion of the ten thousand died as a result of the

effects of the gas. In fact, had it not been for the presence of

mind of some of the officers

who ordered the men to put 17CM MINENWERFER GAS SHELL

wet cloths over their faces and

lie flat on the ground face

downwards the entire force 42,8 1T or

would have been annihilated. Lab

Y.9

Fig. 1 shows a German gas

cylinder in position in the B M n

trench.

Although successful at, times

this form of gas warfare was :FIG. 2. GE RMIAN GAS SHE'LL.

seldom used in the later stages

of the struggle, owing to the inherent disadvantages of the

method. In the first place the wind must obviously be in the

right direction. It must not be too strong-less than twelve

miles per hour-or the gas will be whirled

about and dissipated before the goal is

reached. It must not be too low or it may

change its

direction,

in which case the

offense

may suffer more than the defense.

In the second place, the greatest concen-

tration is at the

wrong end, directly be-

>

G,"

. .

j 1 fore the trenches of the attacking party.

Consequently if the gas is to be followed

by

an

infantry

atta,ck

the offense must

endure more than the defense, or the at-

tack must be delayed until most of the

opportunities created

by the

gas are lost.

A much more effective method

depending

FIG. 3u GtRmAe GAS

SHELL. upon

the wind was

being developed by

the

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE 277

American gas offensive, the details of which are not yet for

publication.

It was soon realized by both sides that some more depend-

able means must be devised to create an efficient concentration

of gas in the enemy's territory and the development of the gas

shell is the result of these researches. Figs. 2 and 3 give sche-

matic views of German gas shells. Gas shells are made for

both large and small caliber guns. The former may deliver

several quarts of the poisonous liquid at a single shot.

For certain kinds of work, gas shells have a great advantage

over even the high-explosive variety. The latter may kill by

direct hit or by the subsequent explosion. The former may do

all this; but in addition the liberated gas may be carried to con-

siderable distance from the spot where the explosion takes place

and gas the enemy who has been protected from the high ex-

plosive by dugouts, etc.

However, the disastrous effects of both the gas cloud and

the gas shell are largely offset by the high efficiency of the mod-

ern gas mask, and this brings us to the second object of the

military strategist, viz., to annoy and hinder, or in military

parlance, to "neutralize" the effectiveness of the enemy. It

will be obvious even to the casual observer that the ability of

the soldier to serve a gun, to shoot or to transport supplies is

greatly reduced if he is obliged to wear a gas mask. In point

of fact it is claimed by military men that the effectiveness of

artillery is cut down sixty per cent., while the infantry fares

scarcely any better, two men being required to perform the

functions of one unhampered by this impediment.

For purposes of "neutralizing," ordinary poison gas may

of course be employed. An occasional gas shell will prevent

the enemy from removing his mask, but his life may be ren-

dered almost unendurable by many substances really not gases

in the accepted sense of the term. Lachrymators or tear gases,

such as benzyl bromide, are heavy liquids which when sprayed

over the ground in small quantities by the explosion will cause

a copious flow of tears for hours if the eyes are not protected

by the gas mask or other device. Moreover the celebrated

"mustard gas," also a heavy liquid, will cause burns on the

skin of such a vicious character that the soldier may be inca-

pacitated for months. A partial list of gases that have been

employed on the battlefield is given below.

Gas Clouds:

Chlorine.

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

278 THE SCIENTIFIC MONTHLY

Shells:

.

........

Phosgene.

Sulfur trioxide.

Benzyl bromide,

German T-Stoff.

Xylyl bromide, German T-Stoff.

Dichloro-diethysulfide, "Mustard Gas,"

German Yellow Cross.

Diphenyl-chlorarsine, "Sneeze Gas,"

German Blue Cross.

Trichlormethyl-chloroformate,

German

Green Cross.

Monochlormethyl-chloroformate,

German K-Stoff.

Nitrotrichloromethane, "Chlorpicrine."

Brominated-ethyl-methyl

ketone.

Dibromo-ketone.

FIG. 4. AN AMERICAN SOLDIER Allyl-iso-thiocyanate.

WEARING A CAPTURED GERMAN REs-

Dichlormethyl

ether.

PIRATOR. The face piece is made of Phenyl carbylamine chlorid

leather.

Hand Grenades:

Bromacetone.

Chlorsulfonic acid.

Bromine. Dimethyl sulfate.

Chloracetone. Methyl-chlorsulfonic

acid.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GAS MASK

When the Germans launched their first gas attack they were

provided with a crude and inefficient device similar to the one

shown in Fig. 6. Later

they developed a much CANISTER OF GERMN

RESPIRATOR

more serviceable mask as

represented in Figs. 4 .

! =L

R

and 5. The British, as

SI-

-A'N

CI

already stated, first em-

ployed a wet cloth. Even

damp earth was found to

have some virtue as a

A

-iranIvks of baked ea'rh o*ekd In7

protection against gas. Potassivu cerhen,tes idol/to

and

covered with powdered charco*l.

In a

very

short time

8-Chareal.

English scientists had c-en?e st-ee enoXad

wlth

devised several types of

FIG. 5.

respirators. These con-

sisted chiefly of cotton wool soaked in photographer's "hypo"

and washing soda. The deleterious effect of the latter upon

the skin was reduced somewhat by adding a small amount

of glycerine. The wool was attached to a

cloth

that was bound

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE 279

around the mouth and nose, as

shown in Fig. 6, or it was held in

the mouth until the cloth could be

placed

in

position. The wool was

then shoved up around the nos-

trils. These primitive masks

would

stop a considerable amount

of chlorine if properly cared for

and adjusted. Unfortunately the

soldier too often dipped them in

the solution and did not suffi-

ciently wring out the excess liquid.

As a consequence he could not

breathe freely, thought he was be-

ing gassed, and frantically re-

peated the operation, often equally FI. 6 EARLT BRITISH RRSPIRATOR.

unsuccessfully. Moreover, the

masks were not carried upon the person, but rather were placed

in the trenches so that the soldier' usually got one that had

been worn by some one else. Beside the obviously unsani-

tary arrangement, another disadvantage presented itself.

When the alarm was given several men frequently rushed for

the same mask with the inevitable result that some of them

were gassed.

A very decided improvement was next introduced in the

form of the " smoke hood." Fig. 7 shows one of the latest mod-

els of these fairly efficient masks. Its great advantage lay in

the fact that the breathing surface was large, resulting in a

very material decrease in resistance. Another prominent fea-

_________________________

ture was the valve that allowed

the exhaled air to escape. It is

made of rubber and is called

technically the "flutter" valve.

I[ 1 So successful is its- operation

for

this purpose that it was subse-

quently adopted in the latest

types of both British and Ameri-

can box respirators.

It was soon realized

by sci-

*! | entists that while "hypo" and

alkalis would take care of chlo-

rine and hexamethylenetetram-

ine would stop large quantities

of phosgene, many other gases,

F0Im. 7. BRITISH SMOKE HOOD. such as the

chemically sluggish

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

280 THE SCIENTIFIC MONTHLY

FIG. 8. THE FRST AmERICAN GAS FIG. 9. THH MOUTH PIECE AND Nosu

MASK. SNUBBERS IN PLACE.

chiorpicrine, could not be~ easily removed by

chemical means.

It was therefore necessary to combine with the chemicals a

universal adsorbent, and carbon, because it has this property

to an

exceptional degree, was chosen for the purpose.

In the

meantime the British had 'invented a mask of extraordinary

efficiency.

The details are given in Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11,

12. Fig.

13

represents

an

early

French

type

of mask.

THE AMERICAN MASK

When the United States of Americ'a entered the World War

the newly organized

American Gas Defense had on its hands

the enormous problem

of

supplyi'ng every soldier who went

abroad with an efficient protection against poison gas, and every

soldier in the concentration camps at home with a mask for

training purposes.

The Gas Defense did not wait to develop

FiG.: 10. THE MOUTH PILECE AND SNUBBERS' FIG. 11. T-HE CANISTPER STANqD-

ING BESIDEI ITS CONTAINER.

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE 281

an ideal device, but wisely

chose to adopt the British

type

of mask.

Incidentally this was

a fine tribute to the British

scientist, because the mask

was mlich superior to any in

use at that time by the Euro-

pean armies. However, Ameri-

can scientists did not rest sat-

isfied with the results of their

allies, but on the

contrary.

be-

gan to develop the existing de-

vices. It has been said that

Americans invent and other

nations improve upon the in-

ventions while we are resting

on our oars. In this particular

instance the tables were turned,

for in a few months we were

producing carbon for gas

masks fifty to one hundred

times as valuable as any known

to our allies and certainly

vastly superior to that which

the Germans were using.

Equally important advances

were made in the soda-lime,

...........

..

FIG. 13. AN EARLY FREN7CH MASK.

(~~~~~~~:8 K

K ' ~~~G

-8

A

FIG. 12. CROSS-SECTIoN AMERICAN

REoSPIRATOR. A is the air inilet. B is

the canister containing granules of soda

lime impregnated with sodium perman-

ganate, and carbon granules about one

quarter the size of ordinary peas. D

is a flexible rubber tube the end of

which, H, is held in the mouth. E, Is

the outlet flutter valve for the exhaled

air. I represents the nose snubbers.

The great virtue of this mask lay in

the fact that the soldier could not be

gassed as long as he breathed through

the tube In his mouth, even if the face

piece became punctured or did not fit

properly.

and the American mask soon be-

came the object of admiration of

both friend and foe. It should

be said in justice to German

chemists that they too succeeded

toward the close of the war in

greatly increasing the efficiency

of their carbon.

DEFECTS OF THE MASK

Every driver of an automo-

bile recalls unpleasant experi-

ences with the fogging or cloud-

ing of the wind shield in cold or

damp weather. The same prob-

lem was met with to an accentu-

ated degree in the gas mask. The

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

282 THE SCIENTIFIC MONTHLY

moisture from the breath or even from the eyes condenses on

the eye pieces, causing them to fog. In cold weather the con-

densation is great enough to create droplets that hang sus-

pended or run down in an irregular manner over the surface.

The result is distorted and obscure vision. The Germans

partially overcame this difficulty by inserting gelatin-like

disks on the inside of the eye pieces. Sooner or later the

gelatin-like substance becomes soft and sags, so that the

vision is imperfect. Several fairly efficient anti-dimming

preparations were compounded by American chemists to be

applied to the inside of the lenses by the soldier before the

mask was required for use. This problem was largely solved

in the latest type of American mask by a very ingenious de-

vice. The intake manifolds were carried up to a point di-

rectly underneath the eye pieces, so that the cold air played on

the lenses, keeping them cool on the inside. As a consequence

the condensation was reduced to a minimum and anti-dimming

compounds were seldom necessary. The nose snubbers and the

rubber tube that was held in the mouth in the old mask were

eliminated in the new type. This was a boon to the soldier, for

he could now breathe in the normal manner through the nose,

thus being relieved to a very considerable extent from the dis-

comfort of the old type mask.

Another defect was discovered in the matter of the construc-

tion of the eye pieces. All the armies were using celluloid be-

cause it would withstand hard usage. It was found, however,

that the surface of the celluloid soon became wavy and the re-

sulting uneven vision caused headaches, indigestion and even

nausea. For this reason triplex glass that will withstand a

severe shock is employed in the latest American mask.

Experience with long-continued wearing of the gas mask

in the field proved that the soldier became exhausted. Some

interesting and valuable physiological experiments revealed the

fact that if one is obliged to breathe against a resistance equiva-

lent to a column of water two to six inches high, an inadequate

amount of air is taken into the lungs to oxygenate the blood

sufficiently. The resistance offered to the air by the contents

of the canister in the American and especially the British masks

was much too high. Consequently the soldier when working

hard did not get enough air to purify his blood and partial or

complete exhaustion resulted. This is believed to have been a

large factor in the collapse of the Fifth British army last March.

The men had been obliged to wear their masks for days because

of the constant bombardment with gas and were exhausted

when the Germans finally attacked.

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PROBLEMS OF GAS WARFARE 283

At the close of the war a new type of canister was being

produced in America in which the resistance was reduced below

the danger point. The new canister was also designed to meet

the requirements of the latest developments of gas warfare, the

" smoke

"

problem. Certain substances, such as sulfur tri-

chloride, were used in gas shells to produce, not gases, but very

fine particles that remain suspended in the air often for long

periods. In the case mentioned the sulfur trioxide unites with

moisture of the air to form tiny particles of sulfuric acid. Many

of these small particles produced in this or a similar manner

were not removed by the contents of any mask in use on the

battle field. The latest American canister gives an almost per-

fect protection against this insidious form of gas warfare.

With regard to gas warfare the American Gas Offense held

the same views as their contemporaries in the field. The best

kind of defense is to strike back harder than the enemy can.

With this end in view enormous quantities of deadly gases, es-

pecially phosgene and "mustard gas," were being produced for

our army at the close of the war and preparations were nearly

completed to increase the production to several hundred tons

per twenty-four hours.

This content downloaded from 193.61.13.36 on Mon, 9 Sep 2013 09:50:49 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Kracauer On BerlinDocument15 pagesKracauer On BerlinVolkan AranNo ratings yet

- Of Art Aand Blasphemy A FisherDocument32 pagesOf Art Aand Blasphemy A FisherVolkan AranNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin - Eduard FuchsDocument33 pagesWalter Benjamin - Eduard Fuchs9244ekkNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin Aura of PhotographyDocument23 pagesWalter Benjamin Aura of Photographykriky100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ArrayList QuestionsDocument3 pagesArrayList QuestionsHUCHU PUCHUNo ratings yet

- Es E100091 Pi PDFDocument1 pageEs E100091 Pi PDFCarlos Humbeto Portillo MendezNo ratings yet

- The History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle NightingaleDocument21 pagesThe History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle Nightingaleapi-166902455No ratings yet

- Pedestrian Safety in Road TrafficDocument9 pagesPedestrian Safety in Road TrafficMaxamed YusufNo ratings yet

- Excellence Range DatasheetDocument2 pagesExcellence Range DatasheetMohamedYaser100% (1)

- Writing and Presenting A Project Proposal To AcademicsDocument87 pagesWriting and Presenting A Project Proposal To AcademicsAllyNo ratings yet

- Pengenalan Icd-10 Struktur & IsiDocument16 pagesPengenalan Icd-10 Struktur & IsirsudpwslampungNo ratings yet

- MySQL Cursor With ExampleDocument7 pagesMySQL Cursor With ExampleNizar AchmadNo ratings yet

- NAVMC 3500.35A (Food Services)Document88 pagesNAVMC 3500.35A (Food Services)Alexander HawkNo ratings yet

- DELA PENA - Transcultural Nursing Title ProposalDocument20 pagesDELA PENA - Transcultural Nursing Title Proposalrnrmmanphd0% (1)

- Plato Aristotle Virtue Theory HappinessDocument17 pagesPlato Aristotle Virtue Theory HappinessMohd SyakirNo ratings yet

- DPCA OHE Notice of Appeal 4-11-2018 FinalDocument22 pagesDPCA OHE Notice of Appeal 4-11-2018 Finalbranax2000No ratings yet

- What Is Architecture?Document17 pagesWhat Is Architecture?Asad Zafar HaiderNo ratings yet

- Imports System - data.SqlClient Imports System - Data Imports System PartialDocument2 pagesImports System - data.SqlClient Imports System - Data Imports System PartialStuart_Lonnon_1068No ratings yet

- CH13 QuestionsDocument4 pagesCH13 QuestionsAngel Itachi MinjarezNo ratings yet

- Energy Efficient Solar-Powered Street Lights Using Sun-Tracking Solar Panel With Traffic Density Monitoring and Wireless Control SystemDocument9 pagesEnergy Efficient Solar-Powered Street Lights Using Sun-Tracking Solar Panel With Traffic Density Monitoring and Wireless Control SystemIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- NMIMS MBA Midterm Decision Analysis and Modeling ExamDocument2 pagesNMIMS MBA Midterm Decision Analysis and Modeling ExamSachi SurbhiNo ratings yet

- Consistency ModelsDocument42 pagesConsistency ModelsPixel DinosaurNo ratings yet

- Policarpio 3 - Refresher GEODocument2 pagesPolicarpio 3 - Refresher GEOJohn RoaNo ratings yet

- Instruction Manual For National Security Threat Map UsersDocument16 pagesInstruction Manual For National Security Threat Map UsersJan KastorNo ratings yet

- Table of Specification ENGLISHDocument2 pagesTable of Specification ENGLISHDonn Abel Aguilar IsturisNo ratings yet

- Corporate Strategic Planning AssignmentDocument10 pagesCorporate Strategic Planning AssignmentSumit DuttaNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument2 pagesResearch ProposalHo Manh LinhNo ratings yet

- Reich Web ADocument34 pagesReich Web Ak1nj3No ratings yet

- Propaganda and Counterpropaganda in Film, 1933-1945: Retrospective of The 1972 ViennaleDocument16 pagesPropaganda and Counterpropaganda in Film, 1933-1945: Retrospective of The 1972 ViennaleDanWDurningNo ratings yet

- Tamil Literary Garden 2010 Lifetime Achievement Award CeremonyDocument20 pagesTamil Literary Garden 2010 Lifetime Achievement Award CeremonyAnthony VimalNo ratings yet

- Tutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19Document98 pagesTutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19kanna2750% (1)

- Risk Assessment For Modification of Phase 1 Existing Building GPR TankDocument15 pagesRisk Assessment For Modification of Phase 1 Existing Building GPR TankAnandu Ashokan100% (1)

- Blank Character StatsDocument19 pagesBlank Character Stats0114paolNo ratings yet

- Space Gass 12 5 Help Manual PDFDocument841 pagesSpace Gass 12 5 Help Manual PDFNita NabanitaNo ratings yet