Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discharge by Frustration (Student)

Uploaded by

Farouk Ahmad67%(6)67% found this document useful (6 votes)

3K views24 pagesThe document summarizes the legal doctrine of discharge by frustration in contracts. It discusses key principles:

1) Frustration occurs when an unforeseen event, beyond the parties' control and not their fault, makes contractual performance impossible or illegal.

2) For frustration to apply, the event must occur after contract formation and radically change the outstanding obligations. Increased expense alone does not suffice.

3) Self-induced frustration does not discharge a party's obligations. The frustrating event cannot be the party's fault.

4) Malaysian courts apply the test from Davis Contractors Ltd. v. Fareham UDC to determine if frustration renders performance "a thing radically different from that undertaken."

Original Description:

Law 486 Contract Law

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document summarizes the legal doctrine of discharge by frustration in contracts. It discusses key principles:

1) Frustration occurs when an unforeseen event, beyond the parties' control and not their fault, makes contractual performance impossible or illegal.

2) For frustration to apply, the event must occur after contract formation and radically change the outstanding obligations. Increased expense alone does not suffice.

3) Self-induced frustration does not discharge a party's obligations. The frustrating event cannot be the party's fault.

4) Malaysian courts apply the test from Davis Contractors Ltd. v. Fareham UDC to determine if frustration renders performance "a thing radically different from that undertaken."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

67%(6)67% found this document useful (6 votes)

3K views24 pagesDischarge by Frustration (Student)

Uploaded by

Farouk AhmadThe document summarizes the legal doctrine of discharge by frustration in contracts. It discusses key principles:

1) Frustration occurs when an unforeseen event, beyond the parties' control and not their fault, makes contractual performance impossible or illegal.

2) For frustration to apply, the event must occur after contract formation and radically change the outstanding obligations. Increased expense alone does not suffice.

3) Self-induced frustration does not discharge a party's obligations. The frustrating event cannot be the party's fault.

4) Malaysian courts apply the test from Davis Contractors Ltd. v. Fareham UDC to determine if frustration renders performance "a thing radically different from that undertaken."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 24

Discharge by Frustration

Dr. Nuraisyah Chua Abdullah

A contract is frustrated, when, after the contract is made, and

without the default of either party, a change of circumstances

occurs which renders the contract legally or physically

impossible of performance.

The common law doctrine of frustration was evolved to

mitigate the strict rule which insisted on a literal performance of

absolute contracts as laid out in Paradine v.Jane. The courts

recognized that where a contract cannot be carried out any

further due to extraneous factors beyond the control of both

parties, the contract is brought to an end forthwith and both

parties are discharged.

The early cases which developed the doctrine of frustration

include Taylor v. Caldwell where the hire of a musical hall had

to be terminated as the hall was accidentally destroyed by fire

six days before the specified concert dates.

In Lee Seng Hock v. Fatimah binti Zain, the Court of Appeal

referred to the doctrine of frustration which has since received

statutory recognition in s57(2) of the Act. S57 of the Contracts

Act makes no reference to the term frustration but uses the

concept of impossibility and unlawful event. Under s57(1), an

agreement to do an act which is impossible in itself is void. This

is explained in Illustration (a) where an agreement wherein A

agrees with B to discover treasure by magic is void.

S57(2) of the Contracts Act provides for the doctrine of

frustration. Under this section, a contract is frustrated when after

the contract has been made, the act: (i) becomes impossible;

or (ii) unlawful. It should be noted that the supervening act

occurs after the formation of the contract and that it is

something which the promissor could not prevent. The section

provides that the contract becomes void when the

supervening event occurs and the act becomes impossible or

unlawful.

Frustration under s57(2) of Contracts Act.

Under s57(2), for the doctrine of frustration to apply, the

supervening event must be one that occurs after the contract

is made. This requirement underlies the rationale for the

doctrine to allow the parties to be discharged for events

occurring after the contract is formed which are not due to the

fault of either party, thus, disabling the performance promised.

In Goh Yew Chew & Anor v. Soh Kian Tee, the appellant

agreed to construct two building on land belonging to the

respondent. The respondent paid $5,000 to the appellants as

earnest money. It was found that owing to an encroachment

of a neighbor's house into the land it was not possible to

construct the buildings according to the plans. The

respondents took action to claim the return of the $5000. The

trial judge found that in the circumstances it was impossible ab

initio to perform the contract. He held that the respondent was

entitled to the balance of the deposit after deduction of all

reasonable expenses incurred by the appellants.

Frustration occurs after the contract is made.

Under s57(2), the supervening event must be something that

the promisor could not prevent. A frustrating event which was

self induced and caused by a default of a party will not

discharge the party from the contract. In Standard Chartered

Bank v. Kuala Lumpur Landmark Sdn. Bhd, Lim Beng Choon J

set out the law governing frustration as follows:

Frustration not self-induced: event which the promisor could not

prevent

It appears that the language of the section envisages two

main instances of frustration - when a contract to do an act

becomes (a) impossible or (b) unlawful.

The frustration should be caused by some supervening and

subsequent event occuring after the formation of the

contract. Furthermore, it should be some event which the

promisor could not prevent, as a self-induced frustration does

not discharge a party of his contractual obligations.

In Yee Seng Plantations Sdn. Bhd. v. Kerajaan Negeri

Terengganu & Ors, the Court of Appeal held that the doctrine

of frustration is in applicable where there is fault on the part of

the party pleading it. In this case, involving an alienation of

land, the Court held that the refusal of the State Executive

Council to alienate the land in question was a result of the

deliberate act of non-compliance of the consent order by the

party to the first action. It was, thus, not a supervening act.

According to the Court, self-induced frustration is no

frustration.

The Contracts Act does not define the word impossible

provided under s57. Malaysian courts have applied the test

formulated by the House of Lords in Davis Contractors Ltd. v.

Fareham UDC where Lord Radcliff stated;

In this case, the appellants agreed to build for the respondents

78 houses within eight months. For various reasons, the chief of

them being lack of skilled labour, the work took 22 months. The

appellants contended that the contract had been entered

into on the footing that adequate supplies of labour and

material would be available to complete the work within eight

months. However, this was not the case and the resulting delay

amounted to frustration of the contract.

Test for frustration

Frustration occurs whenever the law recognises that without

default of either party a contractual obligation has become

incapable of being performed because the circumstances

in which performance is called for would render it a thing

radically different from that which was undertaken by the

contract.

The House of Lords held that the contract had not been

frustrated; the fact that there had been unexpected turn of

events which rendered the contract more onerous than had

been contemplated was not a ground for relieving the

contractors of the obligation which they had undertaken.

In The Eugenia, Lord Dening explained:

To see if the doctrine applies, you have to construe the

contract and see whether the parties have themselves

provided for the situation that had arisen. If they had, there is

no frustration and the contract applies. If they have provided

for it, the contract must govern. There is no frustration. If they

have not provided for it, then you have to compare the new

situation with the old situation for which they did not provide.

Then you must see how different it is. The fact that it has

becomes more onerous or more expensive for one party than

he thought is not sufficient to bring about a frustration It must

be positively unjust to hold the parties bound.

Subsequent to the House of Lords decision in Davis Contractors,

there have been other varied formulations of the test for

frustration. In National Carriers Ltd v. Panalpina (Northern) Ltd,

Lord Simon stated:

Frustration of contract takes place when there supervenes an

event (without default of either party and for which the

contract makes no sufficient provision) which significantly

changes the nature (not merely the expense or onerousness)

of the outstanding contractual rights and/or obligations form

what the parties could reasonably have contemplated at the

time of its execution that it would be unjust to hold them to the

literal sense of its stipulation in the new circumstances; in such

case the law declares both parties to be discharged form

further performance.

In J Lauritzen AS v. Wijsmuller BV (The Super Servant Two),

Bingham LJ set out 5 principles of law on frustration:

1. The doctrine of frustration was evolved to mitigate the

rigour of the common laws insistence on literal

performance of absolute performance;

2. The doctrine is not to be lightly invoked and must be kept

within narrow limits since the effect of the doctrine is to kill

the contract and discharge the parties from further liability;

3. Frustration brings a contract to an end forthwith; without

more and automatically;

4. The essence of frustration is that it should not be due to the

act or election of the party seeking to rely on it but must be

due to some outside event or extraneous change of

situation;

5. The frustrating event must be without blame or fault on the

side of the party seeking to rely on it.

In Malaysia, the House of Lords decision in Davis Contractors

was applied by the Federal Court in Ramli bin Zakaria & Ors v.

Government of Malaysia. In this case, the appellants were a

group of 86 vocational schoolteachers who were successful in

their application for teacher training. One of the conditions of

the offer which they accepted was that the teachers would on

completion of the course be accepted as teachers on the UTS

scale. However, by the time they completed their course of

training , the UTS scale had been abolished and the Abdul Aziz

scheme had come into force. The appellants were offered

salaries under the Abdul Aziz scheme.

The appellants claimed that they should have been paid

salaries and allowances under the UTS scheme. The respondent

pleaded that as the recruitment of teachers into the UTS

scheme had been discontinued, the offer to employ them

under the UTS scheme had become frustrated.

The Federal Court held that the service agreement which

contained the provisions of a particular salary scheme was not

frustrated when the new salary scheme was implemented to

replace the old scheme. Abdul Hamid FCJ stated:

In short it would appear that where after a contract has been

entered into there is a change of circumstances but the

changed of circumstances do not render a fundamental or

radical change in the obligation originally undertaken to make

the performance of the contract something radically different

form that originally undertaken, the contract does not

become impossible and it is not discharged by frustration.

There are two provision besides s57 which are related to

frustration. They are examined below as follows: (i) s33 of the

Contracts Act on contingent contracts; and (ii) s12 of the

Specific Relief Act on partial frustration.

Related provisions on frustration

A contingent contract is a contract to do or not to do

something, if some event, collateral to the contract, does or

does not happen, as defined in s32 of the Contracts Act. S33

provides that if the uncertain future event becomes impossible,

the contract becomes void.

This section brings to focus the difference in application

between s57(2) and s33(b) of the Contracts Act. In cases

where as a matter of construction the contract itself contains,

either expressly or impliedly, a term according to which it will

stand discharge on the happening of certain circumstances,

the dissolution of the contract would take place under the term

of the contract and thus, would be outside the purview of s57.

Contingent contract: s33 of Contracts Act.

In Royal Selangor Golf Club v. Anglo Oriental (M) Sdn. Bhd., the

agreement stipulated that if and when the Land Code was

amended to permit the club to grant to the company a lease

of 99 years, the club would do so. The High Court held that the

agreement became void when the Land Code was repealed

by the National Land Code which did not provide for the grant

of a 99 years lease. The contingent event agreed by the parties

has become impossible to perform and thus, the agreement

becomes void under s33(b) of the Contracts Act.

In Nga Sheau Sheau v. United Nerchant Finance Bhd, the High

Court held that both ss57 and 33 were applicable. In this case,

the plaintiff sued as the widow of Chong Sau Nan, the

deceased. The deceased as borrower and he defendant as

lender had entered into a loan agreement whereby the

borrower agreed to take, and the defendant to approve, a

loan subject to a special express condition that the borrower

take up a mortgage reducing term assurance for a sum insured

equivalent to the value and duration of the loan.

After the loan agreement was executed the borrower passed

away without taking up the mortgage assurance. The Court

held that the death of the borrower resulted in the non-

fulfilment and impossibility of the borrower taking up the

mortgage assurance under the express condition. Thus the

agreement was rendered void under s57(2) of the Contracts

Act. Additionally, the contract in question was a contingent

contract and s33 also applied.

S12 of the SRA provides for partial frustration where only a portion of

its subject matter, which existed at the date of contract, has

ceased to exist at the of performance. Following s12,

notwithstanding s57 of the Contracts Act, the contract may still be

performed.

Illustration (a), A contracts to sell a house to B for $10,00. The day

after the contract is made, the house is destroyed by a cyclone. B

may be compelled to perform his part of the contract by paying

the purchase-money. In this case, the sale of the land can still be

performed.

S12 was referred to in Wong Siew Chong Sdn. Bhd. v. Anvest

Corporation Sdn. Bhd. (No. 2). In this case, the subject matter of the

sale and purchase agreement was land measuring 9,377 sq m.

However, 1220 sq m was latter acquired under the Land Acquisition

Act 1960 (Revised 1992). The Court of Appeal referred to s12 and

held that the part acquired was only a small portion of the contract.

The contract can still be performed and the remaining issue was

payment of compensation for the deficiency.

Partial frustration: s12 Specific Relief Act (SRA)

Effect of war: Berney v. Tronoh Mines Ltd (The High Court

agreed with the defendants contention that consequent on

the Japanese occupation of the State of Perak, the contract of

employment between them and the plaintiff was discharged

by frustration.)

Failure to obtain approval: Yong Ung Kai v. Enting (The

defendant entered into a written agreement with the plaintiff

for the sale of timber on land which the defendants tribe had

communal customary rights. In order to cut the timber, a

license or permit from the forest department was necessary.

The defendant did his best to obtain the necessary license, but

this was refused. The High Court held that when the application

was refused, the contract became impossible to perform.)

However, see Dato Yap Peng v. Public Bank Bhd. & Ors [1997] 3

MLJ 484 where the Court of Appeal that a contract dos not

automatically become frustrated by the mere fact that an

approval was not granted by the relevant authorities.

Instances of frustration

Acquisition of land: Yeo Siew Kiow lwn Nyo Chu Alang & Yang

lain. (The High Court held that when the land became the

subject of acquisition by the state authorities, following s57(2),

the agremeent to sell the land bad become invalid and void

when the land was acquired.)

Detention of employee: Sathiaval a/l Maruthamuthu v. Shell

Malaysia Trading Sdn. Bhd (The court held that the

employment contract of the plaintiff was frustrated by the

plaintiffs detention under the Emergency (Public Order and

Prevention of Crime) Ordinance 1969.)

Effect of injection: Shigenori Ono v. Thong Foo Ching & Ors (The

plaintiff agreed to buy property from the third defendant. The

property was in fact subject to an existing tenancy. The tenant

(third party) took out an injunction against the third defendant.

The High Court held that the contract was frustrated as the

effect of the injunction was that the third defendant could not

carry out his obligations under the contract to the plaintiff. )

In Malaysia, relief for frustration is provided in s66 of the

Contracts Act which provides for restoration of advantage

received for agreement discovered to be void and contract

becomes void.

Besides s66 of the Contracts Act, ss 15 and 16 of the Civil Law

Act 1956 also apply. The provision in s57(3) of the Contracts Act

allowing compensation for loss through non-performance of an

act known to be impossible or unlawful should also be noted.

The phrase Contract becomes void in s66 refers to contract

that become impossible or unlawful under s57(2) of the

Contract Act. Under s2(j), a contract which ceases to be

enforceable by law becomes void when it ceases to be

enforceable. Without any enforceable contract, the only relief

is thus restitutionary which is provided in s66 of the Contracts

Act. Under s66, any person who has received any advantage

under a contract becomes void is bound to restore it, or to

make compensation for it, to the person from whom it was

received.

Effect of, and Relief for frustrated contracts

Illustration (d) in s66 gives an instance of a singer , A, who

contracts to sing for B for $1000. A receives $1000 paid in

advance from B. A is too ill to sing and is required to restore the

$1000 received in advance although A is not bound to make

compensation to B for the loss of profits caused to B due to As

inability to sing.

In Lee Seng Hock v. Fatimah bte Zain, the agreement for the

sale and purchase of land was held to be frustrated under

s57(2) of the Contracts Act when the land was required by the

government. The remaining issues was the appellants claim for

compensation awarded under the Land Acquisition Act 1960.

The court stated:

since wh have already ruled that such agreement is now

void under s57(2) of the Act, the respondent cannot claim any

right to such compensation. At most, he is entitled to be

refunded the 10% deposit he had paid to the respondent

under s66 of the Act It is for this reason that the appellant is

entitled to be refunded the 10% deposit he had made to the

respondent pursuant to clause 1 of the agreement.

Unlike the Contract Act which makes no reference to

frustration s15(1) of the Civil Law Act uses both terms,

contract impossible of performance and frustrated contract.

S15(1) provides that when a contract becomes impossible of

performance or has been otherwise frustrated, the parties are

discharged form further performance of the contract.

Subsection 15(2) to 15(6) of the Civil Law Act provide for the

adjustment of the rights and liabilities of parties to the frustrated

contract.

S15(2) provides that in the case of sums so paid, they are

recoverable as money received for the use of the party whom

the sums were paid, while sum payable cease to be payable.

This means that money which had been paid to any party

before the happening of the event of frustration is recoverable.

For sum which are payable, they no longer need to be paid.

Section 15(2) applies to money paid or payable. Where parties

have conferred benefits other than money before the time of

discharge, s15(3) provides for the recovery of such valuable

benefit.

However, the recovery is not as of right but is subject to the

Courts discretion ad the Court considers just, not exceeding

the value of the said benefit, having regard to all the

circumstances of the case.

It should be noted that for relief whether for sums paid or

payable, or for the recovery of valuable benefit, the Court is

also to have regard to the amount of expenses that may be

incurred by the parties before the frustrating event. This is

provided in the proviso to s16(2) and in s16(3)(a).

S15(2) was applied in by the Federal Court in National land

Finance Co-Operative Society v. Sharidal Sdn. Bhd. to refund

the deposit as money had and received as the contract had

become void upon the refusal of the Foreign Investment

Committee to approve the sale of the immovable property.

In United Asian Bank v. Chun Chai Chai, the High Court held that

the plaintiffs tenancy agreement with the defendant was

frustrated when the plaintiffs had difficulty in obtaining

electricity. According to Lembaga Lektrik Negara, the basic

infrastructure was not sufficient and a substation had to be

constructed. The court held that the requirement of a substation

was so fundamental as to strike at the root of the tenancy

agreement and render a significant change in the obligations

of the party from what was contemplated by them. Therefore,

the plaintiffs were entitled to a refund of sums paid under the

agreement following s15 of the Civil Law Act.

S16 provides that ss15 and 16 applies to contract whether

made before of after the coming into force of this Act. It also

applies to contracts to which the Government is a party but

certain contracts are excluded in s16(5), that is, a charter party,

contract of insurance and certain contracts for the sale of

goods.

Thank you for your attention

You might also like

- Remedies in ContractDocument157 pagesRemedies in Contractzatikhairuddin60% (5)

- Tutor Question 7 (Group 4)Document7 pagesTutor Question 7 (Group 4)Syirah JasriNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Torts IDocument25 pagesPresentation of Torts INuraqilah Shuhada100% (1)

- Undue Influence Summary Contract LawDocument4 pagesUndue Influence Summary Contract LawNBT OO100% (1)

- Froom V Butcher CaseDocument2 pagesFroom V Butcher CaseCasey HolmesNo ratings yet

- Law of ContractDocument7 pagesLaw of ContractIzwan Farhan100% (1)

- The Effects of Exclusion ClausesDocument75 pagesThe Effects of Exclusion ClausesYee Sook Ying100% (1)

- Implied TermsDocument3 pagesImplied TermsChamil JanithNo ratings yet

- Discharge of Contract Lecture NotesDocument8 pagesDischarge of Contract Lecture NotesSazzad Hossain100% (1)

- Contract NotesDocument17 pagesContract NotesAbu Bakar100% (1)

- Business Law Assignment - 3 Core Elements-ScribDocument8 pagesBusiness Law Assignment - 3 Core Elements-Scribjabba7No ratings yet

- Mistake: English Law: To Their Original Positions As If The Contract Has Been PerformedDocument38 pagesMistake: English Law: To Their Original Positions As If The Contract Has Been Performed承艳100% (1)

- 2011 02 01 Occupier's LiabilityDocument11 pages2011 02 01 Occupier's LiabilityAdeyemi_o_olugbileNo ratings yet

- Effects of Uncertainty in The Contract LawDocument4 pagesEffects of Uncertainty in The Contract Lawumair sheikhNo ratings yet

- The Doctrine of FrustrationDocument24 pagesThe Doctrine of FrustrationNelsonMoseM100% (1)

- Distinction Between An Invitation To Treat and An Offer Is Important in Contract LawDocument2 pagesDistinction Between An Invitation To Treat and An Offer Is Important in Contract Lawmohsin100% (1)

- Debt PolicyDocument2 pagesDebt PolicyKathy Beth TerryNo ratings yet

- MisrepresentationDocument4 pagesMisrepresentationJoey Lim100% (3)

- Contract Essay Term 2Document3 pagesContract Essay Term 2Adam 'Fez' FerrisNo ratings yet

- Breach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionDocument5 pagesBreach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionGovnyoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 & 9 - Breach of Contract & Its RemediesDocument47 pagesChapter 8 & 9 - Breach of Contract & Its RemediesEyqa Nazli100% (1)

- Australian Knitting Mills (1936) AC 85, The Plaintiffs Complained of Dermatitis Resulting FromDocument3 pagesAustralian Knitting Mills (1936) AC 85, The Plaintiffs Complained of Dermatitis Resulting FromnaurahimanNo ratings yet

- Offer N AcceptanceDocument15 pagesOffer N AcceptanceRaja Atiqah Raja Ismail100% (2)

- The Federal Constitution of MalaysiaDocument4 pagesThe Federal Constitution of Malaysiauchop_xxNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Common LawDocument16 pagesAssignment 1 Common Lawsakina1911100% (10)

- Discharge NotesDocument3 pagesDischarge NotesHemalatha Aroor100% (1)

- AssignmentDocument12 pagesAssignmentShar Khan0% (2)

- Tort List of Cases According To The Topics 2016Document11 pagesTort List of Cases According To The Topics 2016Amirah AmirahNo ratings yet

- 4 Mistake SummaryDocument5 pages4 Mistake Summarymanavmelwani100% (4)

- Contract Law - Notes (Capacity)Document13 pagesContract Law - Notes (Capacity)PradeepMalikNo ratings yet

- Discharge by FrustrationDocument10 pagesDischarge by FrustrationSylviane Sie Siu MingNo ratings yet

- Discharge of ContractDocument3 pagesDischarge of Contractmalik yasirNo ratings yet

- 6 - Private NuisanceDocument19 pages6 - Private NuisanceL Macleod100% (1)

- Contract Law Tutorial QuestionsDocument2 pagesContract Law Tutorial QuestionspickgirlNo ratings yet

- Topic 4 Law of Contract (Capacity To Contract)Document11 pagesTopic 4 Law of Contract (Capacity To Contract)AliNo ratings yet

- A Levels Law of Contract Intro Itclr 2018Document6 pagesA Levels Law of Contract Intro Itclr 2018preetNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes - ConsiderationDocument3 pagesLecture Notes - ConsiderationAdam 'Fez' Ferris100% (4)

- The Doctrine of Privity of Contract WikiDocument4 pagesThe Doctrine of Privity of Contract WikiKumar Mangalam0% (1)

- Issue of Late and Non-Payment in Construction IndustryDocument8 pagesIssue of Late and Non-Payment in Construction IndustryAbd Aziz Mohamed100% (1)

- Pure Economic Loss & Negligent Misstatements in United Kingdom and Malaysia 2Document24 pagesPure Economic Loss & Negligent Misstatements in United Kingdom and Malaysia 2Imran ShahNo ratings yet

- MistakeDocument3 pagesMistakeshakti ranjan mohanty50% (2)

- Malaysian Legal SystemDocument2 pagesMalaysian Legal SystemAliciaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes - MisrepresentationDocument15 pagesLecture Notes - MisrepresentationAdam 'Fez' Ferris86% (7)

- Remedies For Breach ContractsDocument13 pagesRemedies For Breach ContractsmelovebeingmeNo ratings yet

- Contract Law 2Document199 pagesContract Law 2adrian marinacheNo ratings yet

- Multiple Offers and Acceptance in Contract LawDocument2 pagesMultiple Offers and Acceptance in Contract LawNoor NadiahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Malysian Legal SystemDocument51 pagesChapter 1 Malysian Legal SystemJoshua ChongNo ratings yet

- Duress Lecture LawDocument6 pagesDuress Lecture LawAhmed HaneefNo ratings yet

- TABL1710 AssignmentDocument7 pagesTABL1710 AssignmentAsdsa Asdasd100% (1)

- Free Consent at Contract LawDocument22 pagesFree Consent at Contract Lawalsahr100% (3)

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Malaysian Law PDFDocument23 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To Malaysian Law PDFNur Adilah Anuar100% (1)

- Exemption ClausesDocument37 pagesExemption ClausesAmanda Penelope Wall100% (1)

- 1993 Constitutional CrisisDocument12 pages1993 Constitutional CrisisIrah Zinirah100% (2)

- No 27 Exclusion ClauseDocument6 pagesNo 27 Exclusion Clauseproukaiya7754No ratings yet

- MortgageDocument8 pagesMortgageShruti KambleNo ratings yet

- In Law of Torts AssignmentDocument4 pagesIn Law of Torts AssignmentRohan MohanNo ratings yet

- Judicial ReviewDocument13 pagesJudicial ReviewKiron KhanNo ratings yet

- Frustration - CONTRACTDocument10 pagesFrustration - CONTRACTnishaaaNo ratings yet

- Topic Discharge by Frustration e LearningDocument20 pagesTopic Discharge by Frustration e LearningMuhamad Fauzan100% (1)

- Discharge by FrustrationDocument53 pagesDischarge by FrustrationŠtêaĹeř Raø0% (1)

- Implied Terms Stud - Version2Document40 pagesImplied Terms Stud - Version2Farouk Ahmad100% (1)

- Express Terms (Students)Document51 pagesExpress Terms (Students)Farouk AhmadNo ratings yet

- Exemption Clauses (Stud - Version)Document66 pagesExemption Clauses (Stud - Version)Farouk Ahmad0% (2)

- Discharge by Breach (Student)Document17 pagesDischarge by Breach (Student)Farouk Ahmad0% (1)

- An Offer From A Gentleman - Quinn, Julia, 1970 - Author - Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming - Internet ArchiveDocument3 pagesAn Offer From A Gentleman - Quinn, Julia, 1970 - Author - Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming - Internet Archivew2jjjbyx9zNo ratings yet

- Elearnmarket PPT - AseemDocument23 pagesElearnmarket PPT - Aseempk singhNo ratings yet

- Barangay Assembly DayDocument8 pagesBarangay Assembly DayBenes Hernandez Dopitillo100% (4)

- National Debtline - Factsheet - 12.how To Set Aside A Judgment in The County CourtDocument8 pagesNational Debtline - Factsheet - 12.how To Set Aside A Judgment in The County CourtApollyonNo ratings yet

- Parkway Building Conditional Use Permit Approved - Can Challenge To March 1st 2021Document15 pagesParkway Building Conditional Use Permit Approved - Can Challenge To March 1st 2021Zennie AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Covid Care FacilityDocument5 pagesCovid Care FacilityNDTVNo ratings yet

- Agreement Surat Jual BeliDocument5 pagesAgreement Surat Jual BeliIndiNo ratings yet

- Contract of Lease: Know All Men by These PresentsDocument3 pagesContract of Lease: Know All Men by These PresentsManlapaz Law OfficeNo ratings yet

- 121thConvoList 16 01 2022Document20 pages121thConvoList 16 01 2022shina akiNo ratings yet

- Liberator (Gun) - WikipediaDocument1 pageLiberator (Gun) - WikipediattNo ratings yet

- The Role of A LawyerDocument5 pagesThe Role of A LawyerMigz DimayacyacNo ratings yet

- Claim of Additional Depreciation - One-Time or Recurring Benefit - Claim of Additional Depreciation - One-Time or Recurring BenefitDocument4 pagesClaim of Additional Depreciation - One-Time or Recurring Benefit - Claim of Additional Depreciation - One-Time or Recurring Benefitabc defNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 111713 January 27, 1997 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, HENRY ORTIZ, Accused-AppellantDocument69 pagesG.R. No. 111713 January 27, 1997 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, HENRY ORTIZ, Accused-AppellantJan Wilcel PeñaflorNo ratings yet

- Dubai Event PWC IFSC ShippingDocument1 pageDubai Event PWC IFSC Shippingblack venomNo ratings yet

- State EmergencyDocument28 pagesState EmergencyVicky DNo ratings yet

- Ayshe 1Document11 pagesAyshe 1Márton Emese Rebeka100% (9)

- Final Version Angharad F JamesDocument264 pagesFinal Version Angharad F JamesNandhana VNo ratings yet

- E1-E2 - Text - Chapter 13. CSC AND VARIOUS SALES CHANNELSDocument12 pagesE1-E2 - Text - Chapter 13. CSC AND VARIOUS SALES CHANNELSabhimirachi7077No ratings yet

- Accountant Resume 14Document3 pagesAccountant Resume 14kelvin mkweshaNo ratings yet

- Frozen Semen ContractDocument3 pagesFrozen Semen ContractTony PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Ethical IssuesDocument9 pagesEthical IssuesLove StevenNo ratings yet

- PPM - Environmental Vertical Fund GEF and GCF Templates and Procedures and Policies in POPPDocument4 pagesPPM - Environmental Vertical Fund GEF and GCF Templates and Procedures and Policies in POPPعمرو عليNo ratings yet

- IAS 20 Accounting For Government Grants and Disclosure of Government AssistanceDocument5 pagesIAS 20 Accounting For Government Grants and Disclosure of Government Assistancemanvi jainNo ratings yet

- Risk Management and InsuranceDocument64 pagesRisk Management and InsuranceMehak AhluwaliaNo ratings yet

- M-Xii Corona vs. SenateDocument2 pagesM-Xii Corona vs. SenateFritzie G. PuctiyaoNo ratings yet

- Integration of IndiaMART V2.0Document3 pagesIntegration of IndiaMART V2.0himanshuNo ratings yet

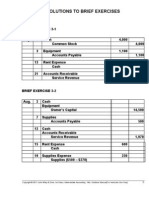

- Self Study Solutions Chapter 3Document27 pagesSelf Study Solutions Chapter 3flowerkmNo ratings yet

- History Pol - Science Mock Test 1 New PDFDocument6 pagesHistory Pol - Science Mock Test 1 New PDFSahil ChandankhedeNo ratings yet

- 2011 Property MCQ With Suggested Answers PDFDocument2 pages2011 Property MCQ With Suggested Answers PDFJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Chris VoltzDocument1 pageChris VoltzMahima agarwallaNo ratings yet