Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research Brief

Uploaded by

api-204451652Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Brief

Uploaded by

api-204451652Copyright:

Available Formats

Kara Holtzman

VOL 1 ISSUE 1

Pull-out or Push-in? What do these terms mean, and how can they best help our struggling students?

The Problem

According to the California Department of Education, only 58% of all students in the state were proficient in English-Language Arts, and only 59% of all students in the state were proficient in Mathematics in 2012. Minority students, English Learners, and Socioeconomically Disadvantaged students are even less proficient in these subjects (CA Dept. of Education). About half of our students are not able to understand the content at their grade level, and that should not be acceptable. What is being done about this? Currently students who are at least a grade level behind in a subject, or an English Learner are receiving additional intervention support through either pull-out or push-in methods which are described below. This research will describe each program, the benefits and disadvantages of each, and give recommendations for successful interventions.

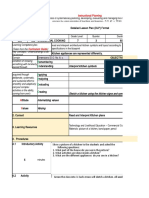

GROUPS Statewide Black or African American American Indian or Alaska Native Asian Filipino Hispanic or Latino Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander White Two or More Races English Learners Students with Disabilities English-Language Arts Target 78.0 % Met all percent proficient rate criteria? No Valid Scores 3,703,587 242,192 24,339 320,777 97,514 1,940,178 20,887 965,542 71,612 1,270,395 426,349 Number At or Above Proficient 2,153,431 110,319 12,120 256,770 73,587 909,541 11,496 714,571 52,592 1,045,644 515,815 152,305 Percent At Met 2012 or Above AYP Proficient Criteria 58.1 45.6 49.8 80.0 75.5 46.9 55.0 74.0 73.4 46.3 40.6 35.7 No No No Yes No No No No No No No No

Socioeconomically Disadvantaged 2,256,393

From CA Dept of Education 2012 State AYP report for EnglishLanguage Arts

Pull-out Intervention

Pull-out teaching is currently the most popular type of intervention for students who are a grade level or more behind in specific content areas. This is described as a method where students receive supplemental content specific or English Language Development instruction one on one or in small groups in a setting away from the regular classroom (Mcclure, Cahmann-Taylor, 2010). One problem with this method is that students are taken out of class during academic content to receive help in another content area. So while they are getting help in one area they are falling behind in another area (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). In an interview with two third grade students receiving pull-out type assistance, they mentioned coming back to class feeling confused and behind because they are missing academic content when they are pulled out of class for reading or speech help.

Another issue is that generally the supplemental practice in the pull-out sessions are not related to classroom content, and just focus on lower-level skills (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). Traditional pull-out sessions are routinized, and focus on a particular weakness. They lack holistic and individualized instruction (Jensen and Tuten, 2007). Due to this lack of individual instruction, and not being connected to classroom content, students stay in a cycle of pull-out interventions throughout elementary school without much success (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999).

Push-in Intervention

Push-in is a more recent intervention teaching method that can be done in several ways. One way particularly for English Language Learners is that an ESL teacher would be brought in as a co-teacher to assist with language content in the regular classroom for all or part of the day (Mcclure and CahmannTaylor, 2010).

A Newsletter for the Education Community

Kara Holtzman

VOL 1 ISSUE 1

Another type of push-in intervention is that a special resource teacher will come into the regular classroom and take one or a group of students aside for supplemental instruction in their areas of struggle. This can be done when the rest of the class is working on the same content area, or it can be done when the other students are working in a different content area (Mcclure and Cahmann-Taylor, 2010). Just like the pull-out method of teaching, the push-in style has its own difficulties. In the method where another teacher is in the room for all or part of the day co-teaching, there are sometimes power struggles between teachers. For example, they may have different techniques, and some classroom teachers do not appreciate the strategies of the resource teachers and make them feel less important (Mcclure and CahmannTaylor, 2010). Another issue is with the push-in methods where other teachers are brought into a classroom for a small period of time to help students with specific content. If both teachers are working on the same content area, then again there can be a power struggle and lack of communication. Or if the resource teacher is supplementing students in a different content area than the rest of the class, those struggling students will get behind in the content they are missing, just like in the pull-out method (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). A 1st grade teacher interviewed about intervention methods stated that she wished all methods were discontinued. She preferred to work with students on her own so that they do not miss valuable academic content when they are gone or with another teacher. Research has shown however, that it is not feasible for the classroom teacher to take over all intervention teaching. Even if they supplement the learning of a small group of students, there are at least 15 other students to try to watch. So the teacher is not fully focused or able to keep the pace necessary for successful interventions (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). So far research shows that students need additional help, but both pull-out and push-in methods seem unsuccessful. Are there any successes with either program, or is there another solution?

Its Not All Bad

Now that both methods have been explained and the issues with each discussed, some positives that each program and additional solutions will be highlighted. Pull-out methods of intervention teaching can be successful, but they require certain elements. One successful program has been a reading improvement program called Reading Recovery (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). The success has been based on several key factors. For reading to improve early intervention is important. Also the pull-out teacher must connect text to students classroom learning, include phonics, reading practice, and writing. The sessions should include no more than 8 children and be approximately 30 minutes per day. This is considered a holistic approach to better reading (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). Another key to success whether it is push-in or pull-out is that there must be clear and understandable goals between the student and teacher. The goal is for the student to gradually improve to grade level and not get stuck in the intervention cycle (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). In the push-in programs, success is dependent upon teacher cooperation. When there are two teachers in a room, both must respect each other, honor their techniques, and collaborate on lessons for the good of the students (Mcclure and Cahmann- Taylor, 2010).

Third graders interviewed stated that even though they miss out on some of the academic content in their classroom, they still feel that being pulled out to get additional help in other areas has helped their academic performance overall. A Newsletter for the Education Community

Kara Holtzman

VOL 1 ISSUE 1

Implications

While both programs have their drawbacks, there are successful ways of implementing both. In one school monitored, half of the students in the Reading Recovery pull-out program mentioned above, met or exceeded grade level reading expectations by the end of the year. This was much more successful than previous traditional pull-out programs based on improving specific weaknesses shown in testing (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). The fundamental ideas of this reading program can be applied to all content area pull-out programs for more success. The program needs to be daily for approximately 30 minutes, students must have clear goals and scaffolding to succeed, content must be connected to classroom work, and assessments must be done to determine when to move forward so that students dont remain at lower-level skills (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999). Push-in programs have also been successful, but require much collaboration between co-teachers. When there is collaborative planning, reflection, and sustained support from school administrators, coteaching has shown student growth in reading and math (Mcclure and Cahmann-Taylor, 2010). Another way that struggling students can be helped is through peer tutors. Research has shown that students who can read at least at a 1st grade level benefit from peer tutors (Wright and Cleary, 2006). Tutors should be one to two grades above the tutee, and be fluent readers. With sessions of twenty minutes each, two times a week, tutors and tutees both showed improved fluency in reading from the increased opportunity to read aloud and receive corrective feedback (Wright and Cleary, 2006). Lack of proficiency in English-Language Arts and Math is a serious issue for all students, but especially socioeconomically disadvantaged, English Language Learners, and minority students. Pull-out, push-in, and peer tutoring can all be successful interventions if instruction is individualized, teaches holistically, and there is collaboration between all teachers involved (Hedrick and Pearish, 1999; Jensen and Tuten, 2007; Mcclure and Cahmann-Taylor, 2010, CA Dept of Education, 2012).

References

California Department of Education (2012). Adequate yearly progress report 2012. Retrieved from http://ayp.cde.ca.gov/reports/Acnt2012/2012APRStAYPReport.aspx. Hedrick, W. & Pearish, A. (1999). Good reading instruction is more important than who provides the instruction or where it takes place. The Reading Teacher, 52 (7), 716-726. Jensen, D.A. & Tuten, J.A. (2007). From reading clinic to reading community. Reading Horizons Journal, 47 (4), 295-313. Mcclure, G. & Cahmann-Taylor, M. (2010). Pushing back against push-in. TESOL Journal 1.1, 101-129. Wright, J. & Cleary, K. (2006). Kids in the tutor seat: building schools capacity to help struggling readers through a cross-age peer tutoring program. Psychology in the Schools. 43 (1), 99-107.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Discipline With DignityDocument3 pagesDiscipline With DignityYlingKhorNo ratings yet

- Constructing A Pie GraphDocument3 pagesConstructing A Pie GraphLeonardo Bruno Jr100% (2)

- Week 7 Methods of PhilosophizingDocument3 pagesWeek 7 Methods of PhilosophizingAngelicaHermoParas100% (1)

- 10 - Preschool and Educational AssessmentDocument15 pages10 - Preschool and Educational AssessmentMARIE ROSE L. FUNTANAR0% (1)

- Historical Foundations of Special EducationDocument10 pagesHistorical Foundations of Special EducationHazel GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Personal and Professional CPDDocument3 pagesPersonal and Professional CPDmaria gorobao100% (3)

- 4 Triangles Lesson-1Document3 pages4 Triangles Lesson-1api-204451652No ratings yet

- Greedy Triangle Lesson 1Document2 pagesGreedy Triangle Lesson 1api-204451652No ratings yet

- Safety SurveyDocument2 pagesSafety Surveyapi-204451652No ratings yet

- Sociogram ReflectionDocument3 pagesSociogram Reflectionapi-204451652No ratings yet

- Directions To Write Your Polygon PageDocument1 pageDirections To Write Your Polygon Pageapi-204451652No ratings yet

- Eds 205 ObservationDocument2 pagesEds 205 Observationapi-204451652No ratings yet

- Extensive and Intensive Listening - EmilDocument8 pagesExtensive and Intensive Listening - EmilClever CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Peningkatan Kecerdasan Intrapersonal Dan Kecerdasan Interpersonal Melalui Metode Bermain Peran Di Kelompok B Paud Titian KasihDocument12 pagesPeningkatan Kecerdasan Intrapersonal Dan Kecerdasan Interpersonal Melalui Metode Bermain Peran Di Kelompok B Paud Titian KasihAstridNo ratings yet

- Parent Teacher ConferenceDocument2 pagesParent Teacher ConferenceRandell AngelesNo ratings yet

- To Whom It May ConcernDocument1 pageTo Whom It May Concernapi-279191943No ratings yet

- Module 4: Lesson 1: Five Model in Planning Science Lessons: A. ActivateDocument3 pagesModule 4: Lesson 1: Five Model in Planning Science Lessons: A. ActivateChe Andrea Arandia Abarra100% (1)

- Department of Education: Weekly Home Learning PlanDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Weekly Home Learning PlanMelody Joy AmoscoNo ratings yet

- 7th Grade Language Arts SyllabusDocument3 pages7th Grade Language Arts Syllabusapi-246746560No ratings yet

- Ratio For April 7Document18 pagesRatio For April 7BertNo ratings yet

- Subject Designs (Subject-Centred Designs) : Question 9: Which Design Do You Think Is Most Likely To Change in The Future?Document5 pagesSubject Designs (Subject-Centred Designs) : Question 9: Which Design Do You Think Is Most Likely To Change in The Future?ン ジョNo ratings yet

- Safety Signs LessonDocument2 pagesSafety Signs Lessonapi-3523290070% (1)

- Worksheet in LPW 012 - 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDocument3 pagesWorksheet in LPW 012 - 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldAltheaRoma VillasNo ratings yet

- Elements & Principles of Design ProjectDocument3 pagesElements & Principles of Design ProjectDion VioletNo ratings yet

- Number The Stars Preread Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesNumber The Stars Preread Lesson Planapi-337562706No ratings yet

- Integrated TeachingDocument3 pagesIntegrated TeachingLaiza Mira Jean AsiaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Task 12Document3 pagesPortfolio Task 12api-287269075No ratings yet

- Case Study - BradenDocument29 pagesCase Study - Bradenapi-190353381No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan Community Learning Center (CLC) Program Learning Facilitator Literacy Level Month and Quarter Learning Strand Ls 1 Ls5 I ObjectivesDocument3 pagesDaily Lesson Plan Community Learning Center (CLC) Program Learning Facilitator Literacy Level Month and Quarter Learning Strand Ls 1 Ls5 I ObjectivesMay-Ann AleNo ratings yet

- FS 2 - Episode 1 Principles of LearningDocument9 pagesFS 2 - Episode 1 Principles of LearningHenry Kahal Orio Jr.No ratings yet

- Week Long Literacy Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesWeek Long Literacy Lesson Planapi-302758033No ratings yet

- What Does It Take To Be An Excellent TeacherDocument33 pagesWhat Does It Take To Be An Excellent Teachernurulhana2000No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in 21st CenturyDocument8 pagesLesson Plan in 21st CenturyJareal007No ratings yet

- Laguna State Polytechnic University: Dr. Josilyn SolanaDocument2 pagesLaguna State Polytechnic University: Dr. Josilyn SolanaRodolfo Esmejarda Laycano Jr.No ratings yet

- Interpreting Kitchen SymbolsDocument6 pagesInterpreting Kitchen SymbolsWilma S. Bentayao100% (1)

- Idu Lesson TwoDocument1 pageIdu Lesson Twoapi-251065071No ratings yet